Clandestine Laboratories

advertisement

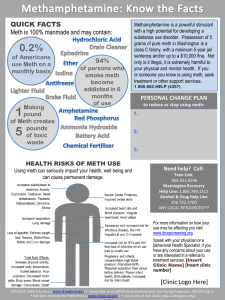

Clandestine Laboratories Clandestine labs are not a new problem for first responders such as the fire service. The article “The Fire Service Should Know about Clandestine Drug Labs” appeared in the November 1970 issue of the National Fire Protection Association’s Fire Command. But today drug labs are usually methamphetamine labs and are in a totally different level that those of decades past. Ad they are more prevalent. In urban areas, small towns, rural fields and abandoned houses and barns—all can, and do sometimes house meth labs. One of the key problems is that methamphetamine (meth) is very simple and inexpensive to make. Most cooks learn to cook from other cooks. Unlike other drugs where there is competition among dealers, meth cooks at times act as a co-op for each other: When one runs out of an essential ingredient, he trades for it with another known cook. Cooks make money by charging other users in their area a fee to teach them to cook. Methamphetamine is easily manufactured (one to four hours, depending on the process) using commonly available ingredients such as pseudoephedrine, sodium hydroxide, lithium batteries, iodine, red phosphorus, sulfuric, ammonia, and/or hydrochloric acids, and organic solvents (Coleman fuel, automotive starter fluid and others). Although the complete list of formulas, hazards, and chemicals employed to produce meth remains extensive, the vast majority of meth laboratories seized today use a common ephedrine/pseudoephedrine reduction method of manufacturing. This method requires a chemical not produced in the United States; however, laboratory operators can find the precursor chemicals needed in many over-the counter cold medicines. Some clan lab operators purchase dozens of bottles of these cold remedies in order to extract the ephedrine or pseudoephedrine from the tablets. Meth cooks sometimes use a formula for production that uses two extremely dangerous and highly volatile chemicals-sodium metal and anhydrous ammonia. Sodium metal can ignite when it comes into contact with water, and anhydrous ammonia is a deadly respiratory hazard. Some clan labs may even contain chemicals such as sodium cyanide, which, if accidentally mixed with another type of chemical found in the same lab, can produce a deadly hydrogen cyanide gas. Clearly, law enforcement teams conducting a clan lab raid always should bring a qualified chemist with them. During the cooking process, laboratories can emit toxic fumes and poisonous gases and cause serious fires and explosions. While the meth outbreak in its earlier stages involved a very few gangs and Mexican organized crime, the Drug Enforcement Administration states that independent, small-scale meth "cooks" currently account for a huge increase in the incidence of this illicit drug. Thus, the growing danger to local law enforcement is in the small, independent criminals labs. These “cooks” often set up their operations in rental properties, farms, hotels and motels, cars, campers, boats and open fields. Since the persons operating these labs have no interest in safety, the labs pose a significant threat to fire service, law enforcement and to the community. Although law enforcement agencies are being forced to divert resources to homeland security and terrorism, clandestine laboratories will continue to threaten the safety of fire service, other first-responders and citizens, in three ways: (1) injuries from explosions and fires, and through exposure to chemicals and toxic fumes; (2) environmental hazards to the community; and (3) child endangerment. The production, distribution and use of illegal drugs have a direct impact on public safety. Fire department responses caused by drug-inflicted problems reduce the resources available for firefighting and other emergency responses. Large quantities of illegal drugs are produced in clandestine drug labs each year in the United States. Though this includes a variety of "designer drugs," in recent years, almost all of the labs seized, as mentioned earlier, were manufacturing methamphetamine. This is a tremendous drain on the Fire departments of all the jurisdictions which have to deal with these clandestine laboratories, especially those in smaller areas with extremely limited budgets. Public safety personnel also face a high potential of acute and chronic health risks when involved in the seizure and handling of the products and residues of these labs. The public is likewise threatened by the potential hazards due to the volatility of the chemicals and the ensuing pollution from the waste that is produced. It is estimated that for every pound of methamphetamine produced, five to six pounds of toxic waste is generated. This waste is discarded with no concern for environmental issues or the potential for exposure to children who may come in contact with the toxic waste. Each clandestine drug lab is unique and can present a number of hazards. A large variety of chemicals could be present, most of which are highly flammable and toxic. The operator may be an experienced chemist who uses sophisticated equipment, or a novice who employs nothing more than primitive or makeshift devices. The operators of these illegal labs may be very astute in preparing the methamphetamine or can be operating from directions passed on to them from others or from recipes found on the Internet. Fire service personnel that are called are then at a distinct disadvantage not knowing what they are going to face at the scene. The chemicals used in the manufacture of methamphetamine can generally be listed as containing dangerous characteristics, including their being: flammable, explosive, irritants, corrosive, carcinogenic, water reactive and cause rapid asphyxia. They can give off noxious gases and vapors. A specific concern exists if red phosphorus is used and it overheats due to improper ventilation. This condition can lead to the creation of large quantities of explosive gas. When any law enforcement agency receives information about the presence of a meth lab, it should plan a tactical operation to seize the lab. This planning process is a police responsibility and that agency's assessment will determine which agencies should respond. The fire department should have a representative present during the planning process to advise the police on the best use of the fire department s resources. The decision on how to proceed with the seizure will be based on the intelligence received about what the site contains. It could include active, inactive or abandoned labs or chemical storage areas. After the information available is gathered and analyzed, the response can be based on the degree of hazard anticipated. The factors involved will depend on the location of the specific site, the amount and types of chemicals, and their concentrations and proximity to each other. The purpose of the initial entry is to secure the scene and apprehend any suspects in the lab. The initial entry team must be specially trained law enforcement personnel who will secure the site as the arrests are being made. Because of the physiological/psychological side effects of methamphetamine abuse, users are often highly paranoid and may not be rational. Proper protection is required by the team and their time spent in the lab should be minimal. Their backup team or rapid intervention crew must be in place prior to the entry by the initial entry team. That team should be composed of DEA-trained law enforcement personnel, not fire personnel. The assessment is carried out once the building has been secured through the arrest and/or evacuation of all occupants. The assessment is conducted by qualified personnel who have been certified in clandestine drug lab operations by the DEA. It should include law enforcement officers and a forensic chemist, all who need to be in the appropriate level of personal protective equipment (PPE). By sampling the atmosphere within the lab they determine the explosive limits, oxygen levels and the extent of toxins present. Their inspection determines any immediate health and safety risks. Deactivation of the lab is accomplished by law enforcement personnel and the forensic chemist. This includes fully shutting down any active cooking processes after thorough analysis to ensure safety of all responders. It can include closing valves on compressed gas, and ensuring that vacuum systems are properly shut down. If necessary, they ventilate the lab and surrounding areas after ensuring that windows and doors are not booby-trapped. The backup team or rapid intervention crew requires the same protection as the assessment team. The team may include fire or police personnel or a combination of both. Fire personnel are not required to be DEA certified, as their responsibilities prohibit them from being members of an initial entry or assessment team. In the event of a fire and/or explosion, fire personnel assigned to backup safety teams will protect escape routes and make rescues if needed. Booby-traps can be well disguised and meant to counter an attack by anyone entering the lab. They can be intended for public safety personnel or rivals intending to steal the contents of the lab. Booby-traps may be set to destroy evidence of the operation. The traps can be very basic or exotic, and in the past have included dogs, snakes, light switches that ignite, and various explosives hooked up to all sorts of things. The violence associated with this powerful stimulant has had a devastating impact on many communities in the West and Midwest. Television viewers nationwide watched live footage of a paranoid meth addict who stole an armored tank from a National Guard armory and went on a car-crushing rampage in the San Diego area. Another meth addict in New Mexico beheaded his son after experiencing hallucinations in which he believed his son was the devil. In Contra Costa County, near San Francisco, police associated meth with 447 cases of domestic violence in 1997. In previous decades, experts viewed meth as "poor man's cocaine" and as a drug abused predominantly by white individuals with low incomes living in rural areas. Today, meth abusers are found in all segments of society and regions of the country, including the previously untouched eastern regions of the United States, with meth use rivaling cocaine as the drug of choice. Meth remains very popular with young people at night clubs and all-night dance parties called "raves." Also, some college students use meth to stay awake and study for exams; athletes may use it to relieve fatigue; and some dieters use it to lose weight. With labs, the risk of explosions, fires, and direct contact with toxic fumes, poisonous gases, and hazardous chemicals always exist. Size does not matter when it comes to the danger level involved in a clan lab raid. In fact, the smaller labs are usually more dangerous than the larger operations because the "cooks" are inexperienced chemists with little regard for safety. In addition to the physical danger, police officers who improperly dispose of toxic waste materials also could be civilly liable under the federal Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, thus making lab raids an especially risky aspect of drug law enforcement. Police officers without specialized training in the unique types of hazards posed by labs never should attempt to investigate or dismantle these "chemical time bombs." Police supervisors must advise their personnel that, if they should inadvertently encounter a clan drug lab, they should not touch anything, and should secure and evacuate the area immediately. Even those officers who have graduated from a qualified laboratory safety school always should remember some fundamental rules of chemical safety when encountering a clan drug lab. (1) Responders must be aware of the equipment used in a clandestine drug lab. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation, law enforcement records indicate that at least three meth lab cooks are killed by explosions or poison chemical incidents each year across the United States. Numerous other cooks receive injuries and burns. Likewise, the number of injuries to responders who mitigate, investigate, and dismantle these labs has greatly increased. Property damage and injuries to the civilian population have also dramatically increased. In the western United States, some cities have reported that meth lab arrests have surpassed driving under the influence/driving while intoxicated arrests. First responders must ensure that they have response guidelines and procedures in place before these types of incidents occur in their jurisdictions. (2) Containers with multilayered liquids can be an indicator of a clandestine drug lab. It has been shown that areas with a high amount of meth abuse also have an increase in domestic abuse, child abuse, unemployment, and violence. Thousands of independent traffickers and cooks operate across this country, and there are increasing numbers of smaller “mom and pop” labs operating in the Southeast. Meth abusers are found in all segments of society, not just in the “poor areas.” Meth remains popular with young people at clubs and all-night parties called “raves.” College students and truckers use meth to stay awake. Athletes use meth to relieve fatigue. Some dieters use meth to lose weight. Although some users may begin taking meth for some of these reasons, they quickly become addicted. Meth is a central nervous system stimulant. Its effects are very similar to cocaine: Users experience increased energy and euphoria. However, the duration of the meth high lasts much longer than that of cocaine, from six to 14 hours. (3) A wide range of household materials and chemicals are used in the production of meth. Meth can be injected, inhaled, and smoked. Chronic users (tweakers) use high levels of the drugs every few hours during prolonged binges that can last for more than a week. With the addicted abusers staying awake for periods up to a week, they begin to experience extreme irritability, increased nervousness, anxiety, paranoia, hallucinations, and violent or erratic behavior from sleep deprivation. Keep in mind that during these binges, the cook/user will often cook more meth, making it easier, because of drug use and sleep deprivation, to make a mistake while performing a complex chemical synthesis. Responders need to be very careful when dealing with these individuals, because they have a high incidence of the following communicable diseases: HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, cholera, and infectious skin disorders. Proper personal protective equipment is a must when dealing with a meth-addicted person. (4) Large and unusual amounts of ephedrine products and other household materials can be key indicators of a clandestine drug lab. One ounce of meth can be produced for around $100 to $200. It sells for $10,000 to $15,000 per pound and $100 per gram. A key issue is that one pound of produced meth will generate up to five or more pounds of hazardous waste. TOP 10 HAZARDS The major hazards encountered at a clandestine lab response are the following: 1. A flammable or an explosive atmosphere. 2. An oxygen-deficient or toxic atmosphere. 3. Leaking or damaged compressed gas cylinders. 4. Clandestine labs in confined spaces. 5. Water-reactive and pyrophoric chemicals. 6. Damaged and leaking chemical containers. 7. Electrical hazards and sources of ignition. 8. Reactions in progress, which can include containers under high heat and high pressure. 9. Incompatible chemical reactions. 10. Bombs and booby traps. Conclusion Without question, the increasing distribution of methamphetamine throughout the United States by international drug organizations remains a serious problem for every law enforcement agency. This threat, compounded by the increasing number of clandestine labs operated by violent criminal organizations, coupled with a growing number of smaller "mom and pop" laboratories, results in an escalating likelihood that law enforcement agencies across the country will encounter more clan meth labs. Impetuous investigations of these clandestine drug labs without proper safeguards may recklessly endanger the lives of law enforcement officers.