An Introduction to Mesopotamia

advertisement

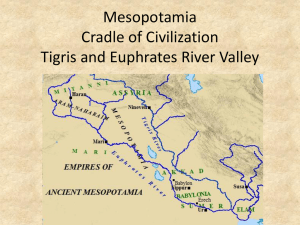

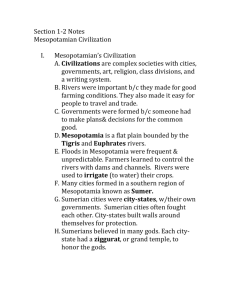

An Introduction to Mesopotamia First settlements The first settlements in the Near East were at places where there was a range of animals and plants but which also had a good supply of fresh water. Some of the earliest are found in the Levant and Palestine (modern Jordan, Israel, Palestine, Lebanon and Syria). From around 12,000 B.C., following the last Ice Age, caves were inhabited or temporary open-air camps and work areas were established. Wild varieties of wheat and barley are common in parts of the region and formed an important part of the diet. Gradually over thousands of years these wild grasses were selected and grown to produce new varieties which were easier to harvest and process. By about 9000 B.C. some of these settlements had become permanent, e.g. at Jericho in the Jordan Valley. By 7000 B.C. people were farming the land - wild grasses and animals had been selected and bred producing domesticated varieties. Religious ideas were expressed in clay models and pottery developed as part of this experimentation with clay. Different regions of the Near East were increasingly exploited. Small agricultural villages grew up across north Mesopotamia sharing styles of pottery and architecture. The people continued to hunt some of the wild animals but increasingly relied on domesticated sheep, goats, pigs, and later, cattle. Mesopotamia Mesopotamia is a Greek term meaning ‘between the rivers' and refers to the land bordered by the rivers Tigris and Euphrates. In modern political terms this covers the country of Iraq and eastern Syria. The region is very diverse with hills and undulating plains in the north where wheat growing and cattle-rearing could be practised. Further south, the rivers are rich in fish and the river banks, which teem with wild animals and birds, were once jungles of vegetation where lions prowled and wild boar could be hunted. The rich wildlife was probably what first attracted humans to the Mesopotamian plain. The southern plain is outside the area of rain-fed agriculture but, over the millennia, the rivers have laid down thick deposits of very fertile silt and, once water is brought to this soil in ditches and canals, it proves a very attractive area to farmers. For materials such as wood, stone and metals, however, people have to look north and east, to the mountains. The southern Mesopotamian plain As far as archaeologists can tell, farmers and fishermen started to settle the southern Mesopotamian plain around 5500 B.C. Over time some of their small villages grew into large settlements. The focus of these communities was the temple of the town's patron god or goddess. The rich farmland provided a surplus of agricultural goods and some of the wealth generated was invested in monumental buildings such as those found at Eridu, Uruk and Ur. Temples and ordinary houses were built using the reeds and mud that line the river banks. Centuries of rebuilding using sun-dried mud bricks resulted in high mounds, or tells, rising above the fields and canals. By the end of the fourth millennium B.C. Uruk was probably the largest city in Mesopotamia. It was centred on enormous temple buildings where archaeologists have discovered beautiful stone sculpture. Here was also discovered some of the world's earliest writing. Using a piece of reed to draw on tablets of clay, administrators recorded the movement of agricultural produce in and out of central storerooms including rations of beer and grain. Initially the records took the form of pictures of the objects being counted, together with signs representing numerals. Gradually these pictographs became more stylised and wedge-like or cuneiform (Latin for wedge = cuneus) and by 3000 B.C. the script was sufficiently sophisticated to write the local language which we call Sumerian. The ability to write allowed the Sumerians to record not only lists of goods but also events around them. This development, therefore, takes us from prehistory to history. Uruk was not the only large settlement in southern Mesopotamia. The wealth of one of these city-states is demonstrated by the Royal Graves of Ur which date to around 2600 B.C. Of the hundreds of graves, excavated by Leonard Woolley in the 1920s, sixteen were particularly rich. Woolley called them ‘Royal' because he believed they were the graves of Ur's kings and queens. The most remarkable aspect of these burials is the large number of human bodies in the pits. These are interpreted as sacrificial victims, accompanying their leader in death. Woolley thought they may have taken poison as he found cups next to some of the bodies. The victims are identified as soldiers, harpists and serving ladies, based on their rich clothes and ornaments made from gold, lapis lazuli, carnelian and shell. Around 2350 B.C. the southern city states were united into one empire by Sargon, king of the city of Agade (also read as Akkad). The administration was centralised and the Semitic language Akkadian (named after Sargon's capital) was introduced as the official language in preference to Sumerian. Agade has not been located but the period produced some astonishing works of art. Sargon and his successors ruled Mesopotamia for 150 years through force of arms. Gradually, however, the Agade empire declined and by around 2100 B.C. many cities reasserted their independence. Chief among these was the city of Ur. Under King UrNammu, the city swiftly established itself as the capital of an empire that stretched beyond southern Mesopotamia onto the Iranian plateau to the east. By this time it appears that the Sumerian language was not widely spoken (it had gradually been replaced by the Akkadian language). However, with this new phase of imperial control, Sumerian was reintroduced as the official language of the dynasty which is known to historians as the Third Dynasty of Ur or Neo-Sumerian Period. Ur-Nammu was a prodigious builder. The most impressive surviving monument of his reign was the ziggurat at Ur. Although similar in shape to the pyramids of Egypt, ziggurats were not tombs but were made of solid brickwork and were stepped. Staircases led up several stages. At the summit was a shrine. From this time onwards ziggurats became a feature of the sacred architecture of all Mesopotamian cities. The rulers of the Third Dynasty of Ur had to fight with groups of people moving into Mesopotamia from the surrounding mountains and deserts, attracted by the wealth of the country. Under Ur-Nammu's great-great-grandson the empire collapsed as Amorite tribes established themselves throughout Mesopotamia. For the next three hundred years the cities of southern Mesopotamia competed for control of the region. North Mesopotamia Further north lay the city of Ashur overlooking an important crossing of the River Tigris. The city dominated the caravans of donkeys carrying metals and rare materials from east and west, and the boats moving to and from the Sumerian cities to the south. As an important trading centre, Ashur had, by 2000 B.C., established commercial colonies in Turkey. Cloth and tin were exchanged for silver. Records of these activities on clay tablets have been found at a number of sites in Turkey. Deeds were often protected by an envelope of clay on which a summary of the transaction was written and sealed with cylinder seals. At the end of the nineteenth century B.C. an ambitious soldier called Shamshi-Adad brought Ashur under his control. He established an empire which stretched across north Mesopotamia. Around 1780 B.C. Shamshi-Adad died and his sons lacked their father's abilities. The empire collapsed and Ashur and the north was now open to attack. When it came it was from the south. Babylonia As king of the city of Babylon, Hammurabi (c. 1792-1750 B.C.) would unite Mesopotamia into a single empire. In the second half of his reign he launched a series of campaigns. Marching north he destroyed the city of Mari and received the submission of many rulers including the king of Ashur. Unlike the rapid collapse of Shamsh-Adad's kingdom, Hammurabi's death did not cause his empire to fall apart immediately but, nonetheless, it did slowly decline. Hammurabi's lasting achievement was that from this time onwards the city of Babylon would remain the capital of the southern plain (Babylonia). However, he is probably best remembered for his code of laws (the famous stela of Hammurabi is now in the Louvre Museum in Paris). In 1595 B.C. the dynasty of Hammurabi was brought to an end when the Hittites from Turkey raided down the Euphrates and sacked Babylon. For the next 100 years or so there is little information to reconstruct events. When evidence becomes available it is clear that Mesopotamia is dominated by two major powers: the Kassites ruling Babylonia and a Hurrian kingdom of Mitanni in the north. Much of what is known of these two kingdoms comes from areas outside Mesopotamia such as Egypt. Assyria Around 1350 B.C. the kingdom of Mitanni collapsed under increasing pressure from the Hittites who were expanding from eastern Turkey into Syria. Mitanni was squeezed between the Hittites and the growing power of Assyria in the east. Assyria now reasserted her independence and began a process of consolidation which included the conquest of much of north Mesopotamia. Around 1200 B.C. the Near East faced conflict and devastation. The Hittite Empire collapsed and Aramaean tribes moved into Mesopotamia from the west, pushing the boundaries of Assyria back to the capital Ashur. By 1000 B.C. various Aramaean and Chaldaean tribal groups competed for supremacy in Babylonia while the Assyrians maintained a firm hold on their homeland, slowly moving against the groups which had settled in the region. At the beginning of the ninth century B.C., Assyrian kings started sending military expeditions north and west in an attempt to control important trade routes and receive tribute from less powerful states. Among the first important kings of the so-called NeoAssyrian period was Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 B.C.). He moved the capital from Ashur to Kalhu (modern Nimrud). The movement of the Assyrian armies towards the Mediterranean continued under Ashurnasirpal's successors. Over the following two hundred years kings such as Sargon and Sennacherib not only built new capital cities (Khorsabad and Nineveh) but expanded the empire. By the time of king Ashurbanipal (669-631 B.C.) Assyrian control stretched from Iran to Egypt. Ashurbanipal boasts in his inscriptions of a peaceful and prosperous reign allowing him time to learn to read and write as well as engage in the royal sport of hunting. However, within twenty years of Ashurbanipal's death Assyria was faced with conflict and eventual destruction. To the east (in modern day Iran) lay the kingdom of the Medes. In 614 B.C. a Median army destroyed the city of Ashur. Two years later the combined forces of the Medes and Babylonians captured Nineveh. The Assyrian empire passed into the hands of Nabopolassar, king of Babylon. The last native empire For sixty years the rulers of Babylon controlled Mesopotamia. Under Nebuchadnezzar II (605-562 B.C.) the city of Babylon was rebuilt on a grand scale. However, in 539 B.C. the armies of the Persian king Cyrus (from SW Iran) marched on Babylon, captured the city and with it the Babylonian empire. Mesopotamia thus became part of the great Achaemenid Persian empire which stretched from Egypt and the Aegean to Central Asia and India. It was to remain under the control of foreign dynasties until the twentieth century A.D.