From World History in Context

advertisement

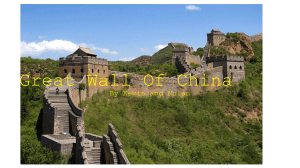

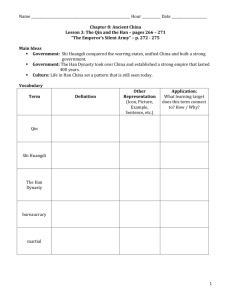

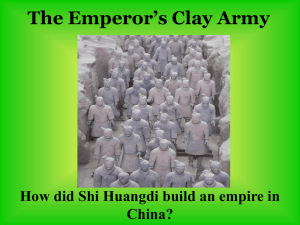

The Xiongnu Empire, 209 BCE Global Events, 2014 From World History in Context Although there was trade between the Chinese and nomadic tribes such as the Xiongnu, the two sides often were in conflict…To keep the Xiongnu and other nomadic tribes out and enclose the area, in 214 BCE the Qin emperor Shi Huangdi (259–210 BCE) began constructing the Great Wall of China to fortify the northern border. When it was completed…, the Great Wall spanned 4,160 miles (6,700 kilometers). In response to such actions, the Xiongnu organized themselves…In 209 BCE Maodun ascended the throne. Taking the title of…shanyu, a title…meaning “the magnificent” or “the great,” he led the Xiongnu on a path of conquest across central Asia…Under Maodun, the formerly nomadic Xiongnu formed an empire. He breached the protective walls and continued to raid in China. [After Shi Huangdi’s reign as the emperor of the Qin Dynasty, the Han Dynasty called] for peace, and the Xiongnu and the Han signed a number of peace treaties, which essentially resulted in the Chinese emperor paying tribute to Maodun…Under these treaties, the Han government recognized the Xiongnu state as a diplomatic equal and promised annual payments in commodities such as silk, wine, and grain…Although the Han government lived up to the terms of these treaties, the Xiongnu raids did not cease. Shi Huangdi Becomes Emperor of a Unified China: 221 bce Global Events, 2014 From World History in Context During his reign, Shi Huangdi ensured his hold on China by basing his government administration on the Chinese philosophy known as legalism…Legalism emphasized strict obedience to the law. According to legalism, people are dishonorable and selfish, so a strong central government with strict rules and harsh punishments is needed to make society function. Thus, in place of the previous feudal system of aristocracy and nobility, Shi Huangdi implemented an autocratic government, with heavy levies and corvée (state-imposed slave labor). To ensure that there would be no dissension about his system of government, Shi Huangdi outlawed all other schools of thought and philosophy. Confucianism was a particular target. He had about 460 Confucian teachers and scholars arrested and burned alive; he also destroyed many of their books. He had most of China’s books and historical records—except for those related to the Qin state and certain philosophical works—collected and burned as well. In addition, he ordered that all weapons belonging to civilians be brought to his capital and melted down. The military was particularly important to Shi Huangdi. He required all the men in China to spend one month each year in military training. Such training was important because Shi Huangdi continually waged wars. He fought the ethnic Xiongnu in the north and conquered the Bai Yue in the south. Buried terracotta figures dating to the third century BCE, Qin Terracotta Warriors and Horses Encyclopedia of Modern China, 2009 From World History in Context Today archeologists have unearthed more than 2,000 of the clay warriors, dozens of bronze horses, and a cache of 30,000 bronze swords, spears, crossbows, and other weapons…Although the practice of burying live people and animals had been abandoned during the Shang Dynasty (1700-1100 BC), it appears that Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi revived it symbolically. Ranks of clay warriors were carefully arranged four [in a row] in long tunnels paved with tightly fitting green bricks and then covered with wooden planks and a layer of preserving clay. The Qin craftsmen gave each warrior a different hairstyle, and each of the faces are painted differently. The specificity of the uniforms, armor, and weapons, as well as the arrangement of the figures into distinct battle units, offers an unusual glimpse of the Qin Dynasty and people's lives at the time. Each figure was individually shaped from coiled clay. Once formed, the figures were fired, cooled, painted, and placed in position. The horses and charioteers were first modeled in clay, and then cast in bronze with handcrafted overlays and painted. All of the faces have distinct characteristics, indicating that the artists had been ordered to model them after live soldiers…[Records] suggest that the bodies of the tomb workers…may have been buried alive to protect the secret of Qin Shi Huangdi’s final resting place. Chinese Emperor mapping the Great Wall of China Gale World History in Context, 2007 From World History in Context What is commonly referred to as the Great Wall of China is actually four great walls rather than a single, continuous wall. The oldest section of one of the four Great Walls of China, was begun in 221 B.C., not long after China was unified into an empire out of a loose configuration of feudal states. The most famous early wall construction is attributed to the first Chinese emperor, Shi Huangdi. Scholars generally credit him with the restoration, repair, and occasional destruction of earlier walls, and ordering new construction to create a structure to protect China's northern frontiers against attack by nomadic people. Historians continue to debate the form these fortifications took. Though records mention the chang-cheng (long wall) of Emperor Shi Huangdi, no reliable historical accounts indicate the length of the Qin wall or the exact route they followed. In 214 B.C., to secure the northern frontiers, Qin Shihuangdi, ordered his general Meng Tian, to mobilize all the able bodied subjects in the country to link up all the walls erected by the feudal states. This wall became a permanent barrier separating the agricultural Han Chinese to the south and the nomadic horse-mounted herdsman to the north. According to historical records, the Great Wall of Qin Shihuangdi was completed in about 12 years by the 300,000-person army, conscripted labor of nearly 500,000 peasants, and an unspecified number of convicted criminals. These workers were subjected to great hardships. Dressed only in rags, they endured cold, heat, hunger, exhaustion, and often cruel supervisors.