file

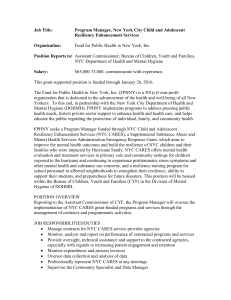

advertisement