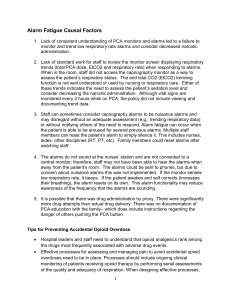

Alarm Fatigue Causal Factors

advertisement

Alarm Fatigue Causal Factors 1. Lack of consistent understanding of PCA monitors and alarms led to a failure to monitor and trend low respiratory rate alarms and consider decreased narcotic administration. 2. Lack of standard work for staff to review the monitor screen displaying respiratory trends (total PCA dose, EtCO2 and respiratory rate) when responding to alarms. When in the room, staff did not access the capnography monitor as a way to assess the patient’s respiratory status. The end tidal CO2 (EtCO2) trending function is not well understood or used by nursing or respiratory care. Either of these trends indicates the need to assess the patient’s sedation level and consider decreasing the narcotic administration. Although vital signs are monitored every 2 hours while on PCA, the policy did not include viewing and documenting trend data. 3. Staff can sometimes consider capnography alarms to be nuisance alarms and may disregard without an adequate assessment (e.g., trending respiratory data) or without notifying others of the need to respond. Alarm fatigue can occur when the patient is able to be aroused for several previous alarms. Multiple staff members can reset the patient’s alarm to simply silence it. This includes nurses, aides, other disciplines (RT, PT, etc.). Family members could reset alarms after watching staff. 4. The alarms do not sound at the nurses’ station and are not connected to a central monitor; therefore, staff may not have been able to hear the alarms when away from the patient’s room. The alarms could be sent to phones, but due to concern about nuisance alarms this was not implemented. If the monitor senses low respiratory rate, it beeps. If the patient awakes and self corrects (increases their breathing), the alarm resets on its own. This alarm functionality may reduce awareness of the frequency that the alarms are sounding. 5. It is possible that there was drug administration by proxy. There were significantly more drug attempts than actual drug delivery. There was no documentation of PCA education with the family– which does include instructions regarding the danger of others pushing the PCA button. Tips for Preventing Accidental Opioid Overdose Hospital leaders and staff need to understand that opioid analgesics rank among the drugs most frequently associated with adverse drug events. Effective processes for assessing and managing pain to avoid accidental opioid overdoses need to be in place. Processes should include ongoing clinical monitoring of patients receiving opioid therapy by performing serial assessments of the quality and adequacy of respiration. When designing effective processes, 1 consider resources such as the American Society for Pain Management Nursing Guidelines on Monitoring for Opioid Induced Sedation and Respiratory Depression (2011). Consider standardized template for hand-offs to improve communication between nurses. Track and analyze opioid-related incidents for quality improvement purposes. Use safe technology such as PCA pumps to control dosing; use monitoring devices to assess for respiratory status changes signaling over-sedation. Provide appropriate education and training to staff, patients and families about the safe use of opioids. Remind staff of the importance of “critical thinking” when administering opioids to patients. Source: The Joint Commission (2012) Tips for Managing Alarm Fatigue Establish guidelines for tailoring alarm settings and alarm limits for specific patients. Not all patients will require the same alarm parameters. Inventory all alarms in high-risk areas to assure alarms are working properly; assess for probability of alarm fatigue. Inspect, check, and maintain alarm-equipped medical devices and base frequency of alarms on criteria such as manufacturer recommendations, risk level of the patient, etc. Identify situations when alarm signals are not clinically necessary and remove them. Ensure hospital leaders understand the extent to which alarm fatigue is occurring in the organization. Without an awareness of the problem, no solutions can be put in place. Observation and open-communication can facilitate a better understanding of the problem. Everyone working in a clinical environment should go through alarm training including what alarms are in use and why. Emphasize that silencing alarms is NOT to be a routine practice without an adequate assessment of the patient’s condition completed by qualified staff. Ensure staff has a systematic way to report equipment malfunctions including equipment where alarms are not providing appropriate alerts (alarming without clinical cause). If staff does not trust that the alarms are working properly, they may tend to ignore the sound. Because alarm sounds are not standardized, assure staff knows how to differentiate the sounds designed to inform them of a potential patient condition change (Oxygen monitor) or potential for risk (fall alarm). 2 Assess monitoring system for best positioning – central monitoring vs. in the room only? Educate patients and families about drug tolerance, expectations concerning pain, the purpose of various alarms, including the alarm sounds so they can alert staff when an alarm goes off. Teach patients and families to report alarms rather than how to silence them. Source: The Joint Commission (2013) 3