Death in Mesopotamia

advertisement

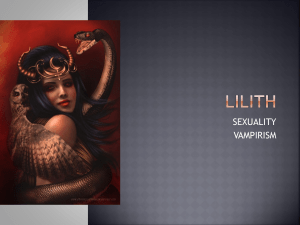

Rachel Steinberg Blue Albritton Death in Mesopotamia “The Mesopotamians seem to have viewed life as a road, a course to be traveled. At the end of the road lay death.” The ancient Mesopotamians had many different rituals and beliefs that took place when a loved one died. This paper highlights the main cultural beliefs regarding death in Mesopotamia. A funeral is a ceremony for a dead person prior to burial or cremation (Dictionary.com). In Mesopotamia, funerals ranged from small ceremonies in one’s house to big services for the whole city to whiteness. Most services were simple and short. People were usually buried with goods such as pottery, ornaments, and food, to later be accessed in the underworld. There was no certain place for the deceased to be buried. Some were buried under the floorboards in their house, some in cemeteries, and some in giant tombs. Usually, people affiliated with temples or palace households were buried in cemeteries because it allowed public display. Where people were buried sometimes caused conflict between the higher class who wanted their tombstone to be larger, or take up a lot of space. The worst way to die was to be burned in a fire because there was no body to be buried. Instead of this person going into the underworld, their ashes traveled up into the sky. It is suggested that the reason for a funeral was either for relatives to stay close to their loved ones or to avoid getting haunted by unburied spirits who were left to wander. 1|Page A funeral service for a king was a very important service for all of Mesopotamia, but even more for the king’s court. During the service, they would go down to the king’s tomb and mourn for a few minutes. Then, out of respect for him and so that he would not have to be alone in the afterworld, they would all drink deadly poison. They would be buried where they fell. Although it is frequently said that the Mesoptamian Gods are immortal, this is only partly true. Only the god Ziusura was granted eternal life, while others would perish. However, Gods did not die from disease, or from the doing of “Demons” as humans did. Most were slain in battle and stripped of a good number of their powers. Although deceased, it was thought that they still had some of their powers and were given offerings and worshiped just as living Gods were. While dead humans usually went to the underworld, it is unclear where dead Gods went. They just seemed to disappear from the picture altogether. "To the land of no return, Ishtar daughter of Sin was determined to go. To the dark house, dwelling of Erkella'a God. To the house which those who enter cannot leave. On the road where traveling is one way only. To the house where those who enter are deprived of light. Where dust is their food, clay their bread. They see no light, they dwell in darkness. They are clothed like birds with feathers. Over the door and bolt, dust has settled." (Babylonian Myth “Ishtar’s Descent into the Underworld”) The Mesopotamian underworld was believed to be as a very dark and gloomy place where the “winged spirits of the dead” were recognized as individuals. Everyone was doomed to permanent 2|Page hunger and thirst unless they got some offerings from their living ancestors. In the afterworld, there was little preferential treatment. Everyone, even kings and their royal courts were doomed to the same torture, however it was said that the horrible conditions of life could be temporarily relieved by music for the very high class. The only other exception to this was stillborn babies, who did not even get to experience earth. This was so that their parents would know that they were safe. The Mesopotamians believed that each God represented some part of nature. The goddess of the underworld was called Ereshkigal. She ruled over the underworld from her palace, Kurnugi which was barred by many gates. Said to be clever and cunning, she waited for spirits trying to escape her palace and got great pleasure in sending them to jail and giving them the appropriate punishment. When angered, her face growed livid and her lips grow black. It is not known exactly what she looks like, however there is a picture of a goddess that is hypothesized to be many different things, including Ereshkigal and her sister, Ishtar. She is called the “Queen of the Night” and has drooping wings, which are associated with the afterworld. Ereshkigal had a very important family. Her father was Sin. Her sister was Ishtar, one of the more important Goddesses; she was the Goddess of fertility, love and war. Her offspring (otherwise accounted her servant) was Namtar, the evil demon, Death. In earlier texts, her husband was noted as Ninazu (otherwise accounted her son). In later text, and more commonly, her husband was noted as Nergal, lord of the underworld. 3|Page Ereshkigal and Ishtar had an ongoing mutual enmity towards each other. This is shown in the Babylonian myth “Ishtar’s Descent into the Netherworld”. In this story, Ishtar, the Goddess of love and war was summoned to go to the Underworld to visit her sister Ereshkigal. When Ereshkigal heard about this, she decided to make a plan to take down her sister once and for all. At every gate barring Ishtar from Kurnugi, she was demanded to take off a piece of clothing, until when she reached her sister, she was completely naked. Ereshkigal knew that if Ishtar was naked when she reached her in Kurnugi, she would lose all her powers and die. Isthar did die, and since she was the Goddess of love, war and fertility, people and animals on earth were becoming infertile. Nergal makes a deal with Dumuzi and Ishtar gets realeased in exchange for Dumuzi. The stripping of Ishtar may have been symbolism of the stripping of the attributes and everyday luxuries of the dead as they travel down into the dim, shady chambers of the Mesopotamian Afterworld. "Mesopotamian [life] focused on the problems of this world and how to lead a good life before dying." Although death is a sad experience in general, the Mesopotamians, although did not embrace it, were accepting of death and its rituals. 4|Page