Crusade

advertisement

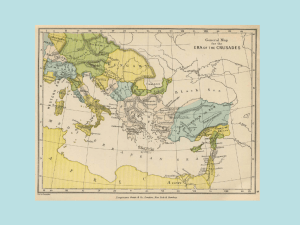

Preparation for Year 12 History Unit 1: The Crusades and the Latin Kingdoms, 1094-1204 SECTION A: Reading Read the article by acclaimed Crusader historian Dr Jonathan Phillips (p.2 of this document) and annotate or make notes about it. Consider: -How has the term ‘crusade’ been used to advance different causes? -Is the term ‘Crusade’ easy to define? Why/why not? SECTION B: Research Go to http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk and then click on the Medieval section. Create a mind map about the Medieval World, including the following areas: Medieval towns, medieval farming, law and order, health and medicine, food and drink, the church and religion, and finally, feudalism and feudal services. (Don’t try to re-write all the information; instead, focus on key facts and information to try to give an overview about medieval life). This work should be completed over the summer, and brought to your first History class in September. The work can be completed on paper or word processed, but a hard copy should be given to your teacher in September. The work should be completed in your own words, and independently. IN ADDITION- to become even better prepared for your course in September (and to really impress your teachers) try to also do the following: Visit the British Museum (it’s free!) and check out the objects in Room 30 (The Islamic World) and Room 40 (Medieval Europe). Watch a documentary about the Crusades- there are lots out there- the best are ‘The Crescent and the Cross’ and Thomas Asbridge’s new 3 part series ‘The Crusades’. Take a look at some medieval maps (lots on the internet). How was the medieval world in the 11th-13th centuries different from today? E.g. what was the Byzantine Empire? The Call of the Crusades By Jonathan Phillips | Published in History Today Volume: 59 Issue: 11 2009 RELIGION SOCIAL CRUSADES MEDIEVAL (4TH-15THC) An idea promoted by Pope Urban II at the end of the 11th century continues to resonate in modern politics. Jonathan Phillips traces the 800-year history of ‘Crusade’ and its power as a concept that shows no sign of diminishing. Pope Urban II preaches the First Crusade at the Council of Clermont. Crusade: according to circumstance, either a toxic byword for conflict between Christians and Muslims or a shorthand for what people believe to be a good and worthy cause. In the former context one might quote Osama bin Laden or, in parallel, the allegations made against Erik Prince, the founder of the Blackwater security company, in Iraq: ‘[he] views himself as a Christian crusader tasked with eliminating Muslims and the Islamic faith from the globe.’ In a more secular arena, any western politician asking for a cut in hospital waiting lists might call for a ‘crusade’. Yet such utterly divergent meanings originate with an idea conceived over 800 years ago, a concept that has produced one of the most long-lasting and adaptable legacies of the Middle Ages. Tracing how ‘crusade’ has evolved, mutated and been appropriated by individuals across the broadest possible spectrum is to follow an intriguing and often surprising trail. In November 1095 Pope Urban II called upon the knights of France to journey to the Holy Land and liberate the city of Jerusalem and the Christians of the east from Muslim power. In return they would be granted an unprecedented spiritual reward – the remission of all their sins – and thereby escape the torments of Hell, their likely destination after lives of violence and greed. The response to Urban’s appeal was astounding; over 60,000 people set out to recover the Holy Land and secure this reward and, in some cases, take the chance to set up new territories. Almost four years later, in July 1099, the survivors conquered Jerusalem in an orgy of killing. While most of the knights returned home, the creation of the Crusader States formed a permanent Christian (or ‘Frankish’) presence in the Levant. In 1187, however, Saladin defeated their forces at the Battle of Hattin and brought Jerusalem back under Muslim control. The Franks held onto other lands until 1291 when they were finally driven out by the Mamluks of Egypt to end Christian rule in the Holy Land. Yet the roots laid down by crusading proved extraordinarily deep, in part because of the idea’s flexibility. In the course of the 12th and 13th centuries crusades were launched against the Muslims of Spain and other enemies of the faith such as the pagan tribes of northeastern Europe (the Baltic Crusades). Further targets included the heretical Cathars of southern France, as well as the Mongols and the Greeks. The preservation or the recovery of Jerusalem was undoubtedly the most important and prestigious of these endeavours and,while certain expeditions (such as the crusade in southern France) were controversial, crusading as a whole took place with the broad approval of European society.As the range of targets shows, crusading was not a static concept. Other developments in medieval society intertwined with and influenced the idea, most particularly chivalry. Crusading offered a platform for knights to show bravery and integrity. The idea of fighting for God, the ultimate lord, gave service in crusading armies a special attraction, although at times knights’ determination to win fame for themselves could cause them to put notions of honour ahead of the greater Christian cause. Crusading was too deeply established within Catholic Europe to disappear after the loss of the Holy Land in 1291. The reconquest of Spain continued; the Teutonic Knights (another military order first set up in the Holy Land) took control of areas of the Baltic and during the late 13th and early 14th centuries many nobles journeyed there to fight the pagans and gain glory. One noteworthy participant was Henry Bolingbroke. Long before he became King Henry IV, the young knight made two visits to the Baltic, in 1391 and 1392, to gain a noble reputation and to serve Christ’s armies; Bolingbroke also went to Jerusalem on pilgrimage in 1393. The Ottomans emerged as the primary focus for crusades and their drive into south-eastern Europe prompted several attempts to rouse new crusading expeditions. The problem was that emergent national identities caused so many deep tensions in the Catholic West that this, combined with a weakening papacy, meant it became ever harder to realise the common crusading cause of centuries past. Sultan Mehmed II captured Constantinople in 1453 and, although the Ottomans reached the gates of Vienna in 1529, their conflict against the Habsburg dynasty had (on both sides) taken on more of an imperial than a religious aspect. Crusading was, by this stage, in steep decline: when the Baltic region became Christianised any justification for crusading was lost; Spain was reconquered by 1492 and the Catholic Church now faced the challenge of the Reformation. Indulgences were attacked as a venal charge on the naïve; no longer was a good Christian required to make an epic journey to the Middle East, he could simply purchase God’s grace by attending a sermon. While similar compromises had long been established, by this stage the feeling that the preachers simply kept the money for themselves meant the idea of indulgence had lost almost all credibility. Perhaps the last crusading battle of note took place at Lepanto in 1571 where a fleet of Spanish, Venetian and Military Order vessels defeated the Turks. The Knights of St John (the Hospitallers) preserved control over their island outposts of Rhodes, until 1523, and then Malta, but otherwise crusading subsided. The advent of Protestantism brought severe judgements on such a papallydirected concept. Thomas Fuller, the English churchman and protohistorian, wrote (c.1639): ‘Some say purgatory fire heateth the pope’s kitchen; they may add, the holy war filled his pot, if not paid for all of his second course.’ By the 18th century and the so-called Age of Enlightenment crusading was disparaged as a worthless, fraudulent charade. In 1769 William Robertson dismissed it as ‘a singular monument of human folly’ and, a few decades later, Edward Gibbon claimed that ‘the principle of the crusades was a savage fanaticism …’and that it ‘had checked rather than forwarded the maturity of Europe’. In mid-18th century France, Voltaire gave crusading an ironic label: ‘une maladie épidémique’. Taking the sickness metaphor further he insisted that leprosy was the only thing that Europeans had gained from the crusades. Yet during the 19th century, crusading, or a mutated form of it, gained new interest in the West. One reason was the writing of Sir Walter Scott whose tales of chivalric endeavour in the Holy Land, most particularly Ivanhoe (1819) and The Talisman (1832), enraptured audiences across Europe. As a Calvinist, Scott’s view of ‘intolerant zeal’ was restrained, but overall he gave a positive impression of the crusades. Scott’s works were translated into numerous languages and in France alone he had sold over two million books by 1840. Ivanhoe alone inspired almost 300 dramas; within a year of its publication, 16 versions of the story were being staged across England. Orientalism was another prominent cultural movement of the time and an interest in the east promoted renewed consideration of the medieval holy wars. In tandem with these developments, the 19th century saw a dramatic expansion of European political power into the Muslim near east, largely at the expense of the declining Ottoman Empire. France invaded Algeria in 1830 and soon afterwards Spain and Italy, too, embarked upon North African adventures. Some looked to the crusades as a forerunner, especially after France took control of Syria in 1920. Paul Pic, Professor of Law at the University of Lyon, regarded Syria as ‘a natural extension of France’, while in 1929 Jean Longnon wrote that: ‘The name of Frank has remained a symbol of nobility, courage and generosity … and if our country has been called on to receive the protectorate of Syria, it is the result of that influence.’ Voltaire insisted that leprosy was the only thing that Europe had gained from the crusades. Yet crusading did not re-emerge solely as a reminder of past glories overseas; the idea was also employed within western Europe. In 1848, during a bid to drive out the ruling Austrians from his Italian territories, King Carlos Alberto launched a half-hearted invasion of Lombardy and Pope Pius IX,who had been unwilling to fight another Catholic country, sent in an expeditionary force under General Giovanni Durando to help him. In an effort to push Pius into open support for the nationalist cause Durando attempted to convince the public that his undertaking had full papal – and therefore divine – sanction. His men advanced dressed as crusaders, complete with crosses sewn on their uniforms. He also issued a press release: ‘Soldiers! … The Holy Father has blessed your swords, which, united now with those of Carlos Alberto, must move in concord to annihilate the enemies of God, the enemies of Italy, and those who have insulted Pius IX … such a war of civilisation against barbarism is accordingly not just a national war but also a supremely Christian one … Let our battle cry be:God Wills It!’ Pius was furious at this arrogation of his authority; he repudiated the war and reminded everyone that he was the head of all Christendom and not just Italy alone.While this particular pseudo-crusade failed, it still shows that the idea was perceived to possess real power. The secular version The outbreak of the First World War provided an obvious arena for a concept associated with moral right. Clearly many other issues formed the propaganda effort on both sides of the conflict, but crusading did feature prominently. Lloyd George made a speech at Conway in May 1916 in which he claimed men were flocking to join ‘a great crusade’ for justice and right. A young Harold Macmillan fought at Ypres in May 1916 and in a letter home to his mother wrote of the devastation of war and the thrill of battle: ‘Many of us could never stand the strain and endure the horrors which we see every day, if we did not feel that this was more than a war – a Crusade. I never see a man killed but think of him as a martyr. All the men (tho’ they could not express it in words) have the same conviction – that our cause is right and certain in the end to triumph. And because of this unexpected and almost unconscious faith, our allied armies have a superiority in morale which will be (some day) the deciding factor.’ Austen Chamberlain, then president of the Liberal Union Association, sketched out his understanding of the crusading cause:‘[We should be wrong] if we thought we are merely embarked in a chivalrous crusade on behalf of another nation, without our interests being engaged … it is not for Belgium only we are fighting. It is not merely a crusade for right and law against wrong and brute force – though it is all of that – but it is a struggle for the vital interests of this country.’ Other than omitting an appeal for divine support, these are all points shared with the earlier crusades and this represents an idealised, secular version of the medieval forerunner. The most apposite setting for parallels with earlier crusades came with General Allenby’s capture of Jerusalem in December 1917. The symbolism of a British commander entering the Holy City was apparent to all and Punch magazine published a cartoon of Richard the Lionheart gazing at Jerusalem saying: ‘At last my dreams come true’, a reference to his failure to take the city during the Third Crusade. For Allenby the link was profoundly uncomfortable. He was acutely aware that a large part of his army were Muslims and that it would be insensitive to describe his actions within a framework of holy war. The fact that the Germans were trying to stir the millions of Muslims elsewhere in the British Empire into a jihad added to the urgency of the situation. The War Office Press Bureau issued a D-notice: The attention of the Press is again drawn to the undesirability of publishing any article, paragraph or picture suggesting that military operations against Turkey are in any sense a Holy War, a modern Crusade, or have anything whatever to do with religious questions. The British Empire is said to contain a hundred million Muhammodan subjects of the King and it is obviously mischievous to suggest that our quarrel with Turkey [the Ottomans] is one between Christianity and Islam. Yet for all Allenby’s efforts to stage a secular, restrained entry into Jerusalem, in the popular imagination the link was too strong. Allenby continued in his attempts to dislodge the connection but the label had stuck and, as we shall see, percolated into the Muslim world too. The Americans also invoked the crusading theme during the First World War. General John ‘Black Jack’ Pershing was the subject of the first official US government war film, made by the US Signal Corps and released in 1918, titled Pershing’s Crusaders. In France, the country most associated with crusading, one recruiting poster proclaimed: ‘Pour achever la croisade au droit’. The Germans also called upon a crusading past and boasted that victory over the Poles in August 1914 was revenge for the defeat of the Teutonic Knights at the Battle of Tannenberg in 1410. The Germans erected a huge memorial on the battlefield and this became the burial place of the esteemed German commander of the day, General Hindenburg, who was represented as a medieval knight. Hitler and the Nazis later adopted these themes and staged nationalist ceremonies at the same site. The last major western figure to draw upon the crusading theme was General Francisco Franco. When the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936 his nationalist movement found common ground with the Catholic Church which became a vital element of Franco’s legitimisation. The Bishop of Salamanca built upon a papal endorsement for the nationalists and published a text, approved by Franco himself, which presented the rebel cause as ‘a crusade against communism to save religion, the fatherland and the family’. Franco argued that: ‘Our war is not a civil war … but a crusade … we who fight are soldiers of God.’ Franco associated himself with El Cid, the hero of medieval Spain who, in reality, had been a hired hand who fought for Christian and Muslim paymasters in the late 11th century, but within decades of his death had been embraced as a hero of the reconquest. Decline and re-emergence The Second World War saw far less crusading imagery. The chivalric aspects of the idea had been torn to shreds on the battlefields of northern France and huge civilian casualties and acts of genocide moved the conflict outside of previous reference points. That is not to say that the notion disappeared – Eisenhower called the D-Day landings a ‘Great Crusade’ and in a more satirical vein Kurt Vonnegut’s novel Slaughterhouse 5 (1969) was subtitledThe Children’s Crusade: A Duty Dance with Death, an ironic recognition of the youth of many American conscripts sent to Europe. While images connected with crusading reemerged in the West during the 19th century, in the lands of Islam the memory of this era (and in some cases the counterpart of the crusade, the jihad),were dormant for a little longer. While some holy war rhetoric pervaded the conflict between the Ottoman and Habsburg empires in the 16th century, jihad sentiments tended to be reserved for the Shia Safavids of Iran. One way in which the memory of the crusades survived was through songs and folklore. Street entertainers recited the Sirat al-Baibars, the story of the fearsome Mamluk sultan who ruled Syria and Egypt between 1260 and 1277. Baibars’ jihad spirit, superb military organisation, harsh discipline and low cunning saw him capture crusader castles such as Krak des Chevaliers to lay the foundations for his successor’s victory at Acre in 1291. An English visitor to Cairo in the 1830s reported about 30 storytellers earning their living exclusively from telling the Sirat al-Baibars. Oral traditions are central to Islamic culture and it is clear that the adventures of the medieval hero – and his opponents, including the crusaders – were extremely popular. With Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798 the West began to encroach on Islamic lands once more, although in this instance the French were keen to stress the absence of a religious edge to their actions.As Napoleon pointed out in a communiqué translated into Arabic: ‘I honour God, his Prophet and the Koran … is it not we who destroyed the pope, the Christian enemy of the Muslims? It was this army who destroyed the Chevaliers of Malta, the ancient enemies of your faith.’ The expedition of Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany is thought to have provided the strongest stimulus to the reappearance of the Muslim world’s other medieval hero (Baibars aside), Saladin. The sultan had enjoyed a fine reputation in the crusading West and Scott’s novels (known to have been read by the kaiser) reinforced this. The kaiser made great play of the dignity, chivalric virtue and statesmanship of Saladin and laid a wreath on his humble wooden resting place in Damascus. The kaiser also paid for the grotesque marble tomb which still stands alongside the sultan’s casket.A couple of decades after this, the first push towards a widescale jihad took place with the pan- Islamic approach of the Ottoman ruler, Abdulhamid II. In his role as caliph (spiritual leader of the Muslim world) and in an attempt to preserve his dynasty’s crumbling empire, he brought the sentiments of the conflict back to the fore with his 1914 call for a jihad. Acting with the encouragement of the Germans, he proclaimed a holy war against the enemies of Islam. While there was relatively little response to this, the profile of Saladin and holy war greatly increased and one or both were soon adopted by a variety of leaders in the Middle East who began to draw a parallel between their own situation and the medieval period. The fact that Saladin had defeated the crusaders and forced them out of Jerusalem seemed even more relevant following the foundation of the state of Israel, although this viewpoint ignored the crusaders’ brutal treatment of Jews in medieval Europe. During the 1950s Arab nationalism came to the fore under the leadership of President Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt.His success in the Suez crisis of 1956 imbued him with the confidence to form the United Arab Republic,welding Egypt with Syria, just as Saladin had done.Nasser looked to Saladin for context and inspiration, reminding his audiences that ‘the whole region was united for reasons of mutual security to face an imperialism coming from Europe and bearing the cross in order to disguise its ambitions behind the façade of Christianity’.His speeches contained frequent references to Muslim victories over the crusaders: ‘Fanatic crusaders attacked us in Syria, Palestine and Egypt.Arab Muslims and Christians fought side by side to defend their motherland against this aggressive, foreign domination. They all rose as one man, unity being the only means of safety, liberty and the expulsion of the aggressors.’ Nasser archly demolished a celebrated, but fictional, phrase by Allenby in 1917.He asserted that the westerners ‘had never forgotten their defeat [by Saladin]’ and wanted revenge in another ‘fanatical, imperialist, crusade’. Nasser then ‘quoted’Allenby: ‘when he entered Jerusalem during World War One he [the general] said: “Today,we end the fight of the Crusaders who were defeated 700 years ago.”’Nasser’s use of this statement shows why Allenby strove so hard to uncouple the tie between the medieval crusades and his own experiences – and it demonstrates just how completely he had failed to do so. Another medium through which Nasser’s message was transmitted was Youssef Chahine’s 1963 film Salah ad-Din Nasser in which Saladin leads the Arabs to victory against the treacherous crusaders.After the Battle of Hattin the sultan proclaims that ‘Jerusalem has been returned to the Arabs’.While Islam was important to Arab nationalism, the creed was based on regional and cultural identity, rather than faith. Most of the Christians in the film are bellicose, greedy and duplicitous, with Richard the Lionheart a noble exception – the worthy opponent of the great Saladin. Showing a humanity that some of his fellowcrusaders lack, the English king worries about the losses of troops and this eventually brings him to the negotiating table. Saladin points out that ‘Jerusalem belongs to the Arabs’ and he tells Richard to inform the people of the West that ‘war is not always the solution’, another reflection of Nasser’s desired image. His rival acknowledges the Arab victory and the Lionheart is received by the sultan at the gates of Jerusalem (a completely fictitious scene – the two men never met). Nasser died in 1970 but the enthusiastic identification with Saladin was taken up by the Syrian leader Hafiz al-Asad, a man determined to oust the ‘neocrusaders’ in Israel.When former US President Jimmy Carter visited Asad in Damascus in 1984 he saw a huge mural on his office wall depicting Saladin’s victory at Hattin. Carter noted: ‘As Asad stood in front of the brilliant scene [the picture] and discussed the history of the crusades and the other ancient struggles for the Holy Land, he took particular pride in retelling tales of Arab successes, past and present.He seemed to speak like a modern Saladin, feeling that it was his dual obligation to rid the region of all foreign presence.’ The most public legacy of Asad’s admiration for Saladin stands in front of the citadel of Damascus: an equestrian statue of the sultan flanked by a Sufi holy man and a jihad warrior and trailed by two defeated, dejected crusaders. The message is obvious: as Saladin triumphed over the crusaders, so will Asad. The most recent nationalist leader to invoke Saladin was Saddam Hussein. The two men shared the same birthplace – Takrit – a fact the Iraqi leader made much of. Children’s books,murals and postage stamps connected him to the man who had defeated the Christian West, although Saladin’s Kurdish origins were conveniently ignored by a man who persecuted his modern counterparts so ferociously. In contrast to these largely secular emphases, Osama bin Laden’s pronouncements have portrayed conflict with the crusading West in strongly religious terms. Jihad is a central concept to the Islamic faith, unlike crusading which was invented centuries after Christ. There is the higher jihad, that of the soul, and the lesser jihad which seeks to bring the world under the sway of Islam. Like crusading, there is also a defensive aspect to the jihad, frequently invoked by nationalists and Islamists alike. According to the Koran, if Muslim lands and/or Islamic belief are attacked then it is a religious duty to resist – if too few of the faithful are present to do so, then neighbours should assist: ‘Yet if they ask you for help, for religion’s sake, it is your duty to help them.’ Bin Laden calls upon this to combat what he terms a ‘Judeo- Crusader alliance’ against Islam. He addresses his appeal to the Muslim community as a whole and he frames the conflict in religious terms rather than the imperialist struggle employed by Arab nationalists. When President Bush so disastrously used the word ‘crusade’ in his unscripted response to the 9/11 atrocities he simply fulfilled the claims Bin Laden had been making for years: ‘So Bush has declared in his own words: “Crusader attack”. The odd thing about this is that he has taken the words right out of our mouth.’ He deftly turned Bush’s words against him: ‘So the world today is split into two parts, as Bush said: either you are with us, or you are with terrorism. Either you are with the Crusade or you are with Islam. Bush’s image today is of him being in the front of the line, yelling and carrying his big cross.’ One further role awaits Saladin in 2010.Demonstrating his extraordinary adaptability he will star in a new cartoon series as ‘the ultimate hero: courageous in the face of danger, never willing to admit defeat and funny when he needs to be’.To take a figure with such a huge historical reputation is an intriguing move. While openly fictional, the makers (al-Jazeera Children’s TV) have taken a period in his career when the young man learns the lessons of life needed to make him the great leader he became. The crusades are part of the backdrop, although in the trailer they are described in neutral terms as an invading army from the West, rather than anything more polemical. In fact, one of Saladin’s friends is a Frank, although Reynald of Chatillon (Saladin’s prime foe) provides a justifiably sinister villain. Crusading has been taken as a more distant metaphor in countless other circumstances – the Women’s Temperance Crusade in the USA of the 1870s or the Jarrow Crusade of 1936 are two examples of note. All have helped preserve this centuries-old idea. Since the efflorescence of interest in crusading in the aftermath of 9/11 in 2001 and the Madrid bombings in 2004 and, especially with the controversy over President Bush’s use of the word, there has been a greater awareness of the historical context of ‘crusade’ and the negative connotations that it carries in the Muslim world. It is worth remembering, too, that the Greek Orthodox church has remained angered by the events of 1204 when the Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople; in the summer of 2001 senior Greek clerics compelled Pope John Paul II to apologise during a visit to Athens. Of course, while it is easy to draw parallels between the medieval and modern eras, the call to the First Crusade bears only a limited resemblance to the colonial and imperial enterprises of the 19th centuries because it was conceived as a war to recover territory, rather than as an aggressive acquisition of new land. Nonetheless, a crusade in the sense of fighting for a good cause with a moral right continues to prove a potent and alluring concept across the western world, albeit one that politicians are now considerably more wary of. Saladin, meanwhile, the crusaders’ greatest rival, continues to maintain the highest of reputations across both Sunni Islam and in the West.