saes1ext_abstract_ch08

advertisement

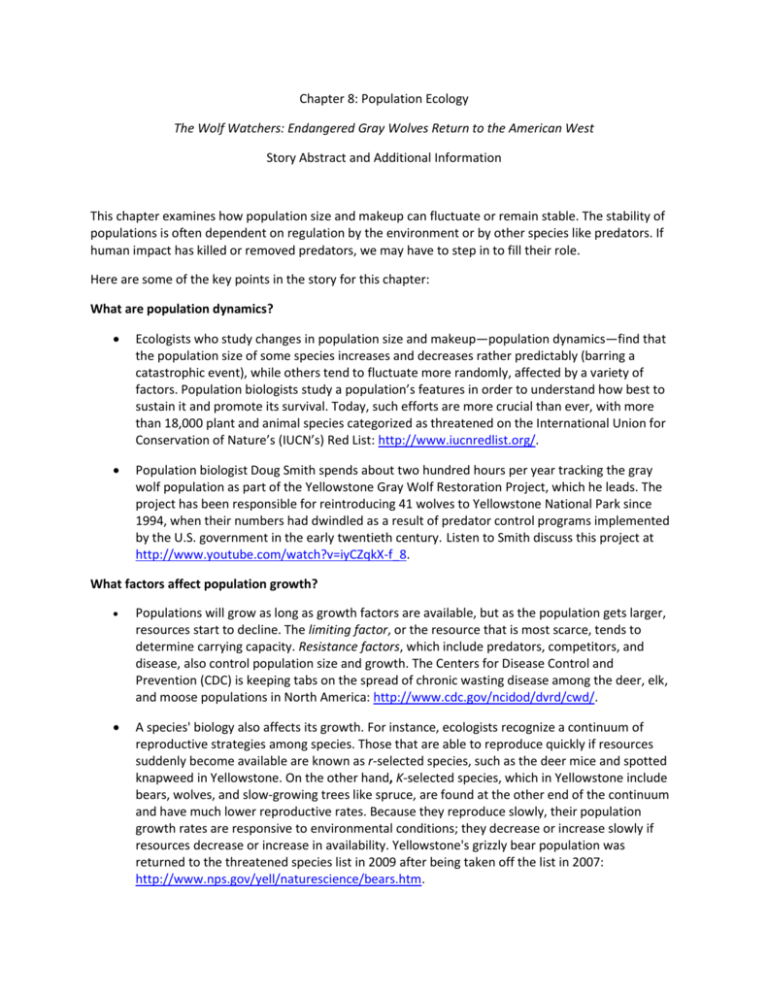

Chapter 8: Population Ecology The Wolf Watchers: Endangered Gray Wolves Return to the American West Story Abstract and Additional Information This chapter examines how population size and makeup can fluctuate or remain stable. The stability of populations is often dependent on regulation by the environment or by other species like predators. If human impact has killed or removed predators, we may have to step in to fill their role. Here are some of the key points in the story for this chapter: What are population dynamics? Ecologists who study changes in population size and makeup—population dynamics—find that the population size of some species increases and decreases rather predictably (barring a catastrophic event), while others tend to fluctuate more randomly, affected by a variety of factors. Population biologists study a population’s features in order to understand how best to sustain it and promote its survival. Today, such efforts are more crucial than ever, with more than 18,000 plant and animal species categorized as threatened on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s (IUCN’s) Red List: http://www.iucnredlist.org/. Population biologist Doug Smith spends about two hundred hours per year tracking the gray wolf population as part of the Yellowstone Gray Wolf Restoration Project, which he leads. The project has been responsible for reintroducing 41 wolves to Yellowstone National Park since 1994, when their numbers had dwindled as a result of predator control programs implemented by the U.S. government in the early twentieth century. Listen to Smith discuss this project at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iyCZqkX-f_8. What factors affect population growth? Populations will grow as long as growth factors are available, but as the population gets larger, resources start to decline. The limiting factor, or the resource that is most scarce, tends to determine carrying capacity. Resistance factors, which include predators, competitors, and disease, also control population size and growth. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is keeping tabs on the spread of chronic wasting disease among the deer, elk, and moose populations in North America: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/cwd/. A species' biology also affects its growth. For instance, ecologists recognize a continuum of reproductive strategies among species. Those that are able to reproduce quickly if resources suddenly become available are known as r-selected species, such as the deer mice and spotted knapweed in Yellowstone. On the other hand, K-selected species, which in Yellowstone include bears, wolves, and slow-growing trees like spruce, are found at the other end of the continuum and have much lower reproductive rates. Because they reproduce slowly, their population growth rates are responsive to environmental conditions; they decrease or increase slowly if resources decrease or increase in availability. Yellowstone's grizzly bear population was returned to the threatened species list in 2009 after being taken off the list in 2007: http://www.nps.gov/yell/naturescience/bears.htm. What are boom-and-bust cycles? Predator and prey also respond to each other; predator populations increase as their prey population increases. In some cases, the fluctuations in population size are large enough to result in boom-and-bust cycles, with the predator’s population peaks lagging behind those of its prey or food source. A classic example comes from an island called Isle Royale in Michigan. Watch this video to learn more about the wolf and moose populations on this island: http://www.techtube.mtu.edu/watch.php?v=1150. Yellowstone saw this boom-and-bust cycle after the wolves began to be reintroduced. According to the National Park Service, the elk population in Yellowstone doubled between 1914 and 1932, a direct result of wolf extirpation (local extinction). These elk then began exerting pressure on their food sources. Willow trees were overgrazed because elk like to eat the tender young shoots. As the wolf population increased again after reintroduction, the elk spent less time in willow stands, preferring to be out in the open where they could see their predators. The willow population is now recovering: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/12/111221140710.htm. Additional information about other topics from this chapter: Gray Wolf Restoration Project The U.S. gray wolf population is also faring well. There are now more than 5,000 gray wolves living in the lower 48 states, approximately 100 of which are in Yellowstone National Park. Read more about the restoration project at http://www.nps.gov/yell/naturescience/wolfrest.htm. Not everyone was in favor of reintroducing wolves, and opposition remains today. Ranchers in particular were and still are wary of the damage wolves might do to livestock. The Defenders of Wildlife organization works with ranchers, educators, the public, biologists, and agencies to build support for wolf recovery. The group runs a wolf compensation program, which pays ranchers full market value for livestock lost to wolves: http://www.defenders.org/programs_and_policy/wildlife_conservation/solutions/wolf_compen sation_trust/index.php.