Lesson Plan

advertisement

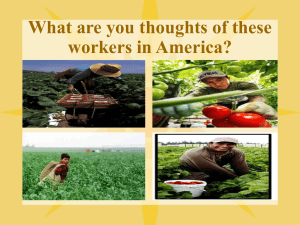

Cesar Chavez/Bracero Program Lesson Plan Spanish for Native Speakers January, 2012 (near MLK Day) Guiding Questions Who was Cesar Chavez? What did he stand for, and why is his influence so important today? What was the Bracero Program and how was it related to Cesar Chavez and the history of Mexican migrant workers in the United States? How did the Bracero Program affect migrant farm work, both when at the time it was happening and now? Objectives Students will understand the historical significance of Cesar Chavez as related to Mexican American migrant workers, unions, strikes and peaceful demonstrations (and hopefully be able to make a connection with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.). Through doing observations of primary sources, and then discussing those sources, students will understand what the Bracero Program was, when and why it was instituted in the United States, and what the ramifications of it were for the Mexican migrant worker here in the U.S. Background Information One can educate oneself about the Bracero Program here: http://www.sites.si.edu/exhibitions/exhibits/bracero_project/main.htm There were pros and cons of the program—Many Mexican workers felt that it was a huge privilege to be involved in the Bracero Program, because they were so poor, and the pay, by Mexican standards, was generous. At the same time, there were farm owners who did not treat their workers well. There were often issues with pay, or a lack of pay, and the work conditions could be awful. Cesar Chavez and the farm worker movement helped bring awareness to the American public, as well as Mexican workers and farm owners, and it helped to bring the Bracero Program to an end in 1964. Lesson Overview Students will make observations of several primary source photographs, in order to build background knowledge about Cesar Chavez’s life, the issues he stood for and the time in which he lived, as well as the Bracero program. Students will become familiar with at least one written primary source relating to the time period in question (the late 1960s to 1993) and produce a piece of free verse “found” poetry from that source. Key Vocabulary La Huelga (Strike); Si se Puede (It can be Done); Union; Farm workers Association; Bracero; stoop labor; fumigate; inoculate; Department of Labor; cartito (short-handled hoe); calloused hands; DDT; labor shortage; controversy; civil liberties; indentured service; propaganda Materials – Day One Thinking about Primary Sources observation sheet (one per student or small group of students) One set of primary source photographs from Cesar Chavez’s life, numbered 1-5 for each small group The same photographs need to be available digitally, so that I may share them with the class for the follow-up discussion. Chart paper, to write down a timeline of Cesar Chavez’s life. (We didn’t get to this step—kids were very engaged with the photos and wanted to talk about them.) Photo Links Photo One (Park Sign: This Park was given for White People Only) - http://www.pbs.org/itvs/fightfields/timeline.html Photo Two (Boycott Lettuce and Grapes Poster) - http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/93505187/ Photo Three (1972 Photo by Manuel Echevarria – taken at the U.S./Mexico border) – page 34 of the following document: http://chavez.cde.ca.gov/ModelCurriculum/Teachers/Lessons/Resources/Biographies/High_School_Bio.pdf Photo Four - National Farm Workers Benefit Concert Flyer - http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/90716478/ OR http://www.americaslibrary.gov/aa/chavez/aa_chavez_peace_1_e.html Photo Five – p. 33 of the following document- Cesar Chavez, breaking his fast with Robert Kennedy, 1968 http://chavez.cde.ca.gov/ModelCurriculum/Teachers/Lessons/Resources/Biographies/High_School_Bio.pdf Photo Six – Octavio Ocampo Painting (copyrighted, I am sure) - http://www.pbs.org/itvs/fightfields/cesarchavez2.html Day 1 – Observing Primary Sources Set 1 Students will arrive. I will introduce myself and explain that today we are going to examine primary source photographs. I will not tell students what the photos are of, but I will say that I would like them to view the photos in order, and fill in the observation sheet I will give them that asks for three things: 1. What do you observe? 2. What do you think you know, and 3. What do you want to find out? As students make observations, I will try hard to not give away what the photos are of by facilitating with such statements as: ”Why do you think that?” “What did you see in the photo that makes you say that?” “Did anyone else observe anything else that seems interesting or significant in this photograph?” “What time period do you think this photo is from?” “Where do you think this photo was taken? What kind of event?” “What type of primary source is this?” (Magazine article, newspaper, etc.) “Was there an audience for this primary source? Who was the audience?” “Do you think this/these photos were posed? Why or why not?” “Whose point of view is represented, if you think there’s a point of view represented?” After students make observations on their own, we will come back together as a class and look at the photos on the LCD projector and discuss their observations, above. After each photo and its discussion, I will give students the background on that photo. To wrap up day one, and to tie Martin Luther King and the idea of peaceful demonstrations into this conversation, I had students listen to the following story from NPR: Examining King’s Influence on Latino communities: (NRP story from January 2008) http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=18272160 If time permits, I would also like to create a very “loose” timeline of Cesar Chavez’s life in relation to when/where/why the photos were taken. Materials – Day Two Primary Source Essay: The Most Memorable Time of Our Lives by Ray Huerta (available on Gale Biography database) Primary Source Writings translated into Spanish: “Latino Consciousness.” American Decades Primary Sources. Ed. Cynthia Rose. Vol. 7. 7: 1960-1969. Detroit: Gale, 2004. 348-351. Gale Biography in Context. Web. 16 Jan. 2012 (Also available through MCPLD Gale Biography Database.) Three sources: 1. The Mexican American and the Church 2. Prayer of the Farm Workers’ Struggle 3. We Shall Overcome Construction paper, scissors, glue sticks Day 2 – Found Poetry Initially, the first part of this lesson was to read a primary source piece of writing about the time of Cesar Chavez: the Most Memorable Times of our Lives, 1968-1972 by Ray Huerta, a Mexican-American who worked as an organizer for the UFW from 1968 to 1975. However, I did not do this part – the reading was a longer one, and students were very engaged from Day 1. Instead, we read the Primary Source “The Prayer of the Farm Worker’s Struggle” (a prayer written by Cesar Chavez) and then I let students create found poetry using this primary source. Since I found the prayer on a Gale Database, and one of the resources on that database is a translation tool, I translated the prayer into Spanish and let the students choose if they wanted their poem to be in English, Spanish, or a combination of both. I changed to the text to a larger font and double spaced it so that it was easier to cut up and paste onto construction paper. Characteristics of Free Verse Poetry: No set line length, no set rhythm, no rhyming pattern, it’s a way of conveying feelings and ideas, it can be a carefully crafte4d word picture. Materials – Day Three Look Magazine Article – September 29, 1959 (See attached—I got this article from the Look Magazine archive at The Library of Congress when I was there last summer.) Thinking about Primary Sources worksheet Day Three – Observing Primary Sources Set 2 Basically, we are doing the same thing we did Day 1. Students will be put into groups of 2-4 students, and given their second set of primary sources—this time, they will all be observing the Look Magazine article about Clemente Mendoza. (This article is a sort of glamorized account of what it is like to be a Bracero. One of the interesting things in this article, and in other primary source photographs I found, is that Braceros were often sprayed with DDT—there is a photograph of Clemente being sprayed. Kids were pretty appalled at this photo, but the more I thought about it, and after talking with my father and others whose parents worked in the outdoors at all during that time, DDT was a pretty pervasive substance.) Materials – Day Four On the fourth day, we did one more set of primary source photographs. This time, each group got different photos. Many of the photos were from a traveling Smithsonian exhibit (Bittersweet Harvest: The Bracero Program). Go to this link to learn more about the program, and to get photographs to use with kids. Basically, we used the “Thinking about Primary Sources” page the same way we did the previous two times, and then at the end, we went from group to group, and each group had a chance to talk about the photographs they had, and I was able to share what I knew about the photos. The following photo, in particular, is interesting, because the Bracero is holding a short-handled hoe. Farmworkers were often asked to use these hoes because it forced the user to be more precise and crouch way down to work with the plants in the fields. The cartito (short-handled hoe) was something that Cesar Chavez worked hard to have banned because to use one was such back-breaking work. Projects/Lesson Extensions -Find someone who was a bracero, or find a student who is related to a bracero, and have that person be a guest speaker or brainstorm questions for that person to answer (if they still live in Mexico). -Have kids find or pick one or two photographs of Mexican migrant workers, Cesar Chavez, braceros, unions, or any related topics, and research those photos as best they can. To extend this project, one could have students answer questions that ask them to draw their own conclusions or solve a problem regarding their research topic. -Tie in the teachings of Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr. and others who promoted peaceful methods of demonstrating. Learn about unions and the history of unions. Students could be asked to research a topic that they think is unjust and figure out what an appropriate way to demonstrate about that topic, choosing a purpose for the demonstration (to educate the public, to get someone who is in charge of something to change a policy, etc.). The demonstration wouldn’t have to actually happen, but it could be effective to talk about the ways that change actually happen in our society. -At the completion of this project, it could be very effective to find Hispanic Americans to come to class and talk about their careers, and to do a project/unit on career planning with your students. The teacher I worked with was teaching a group of Hispanic kids, who were all native Spanish speakers—these kids were very engaged in this entire project. In Conclusion Something really cool happened when we taught this unit: One of the students went home and talked with her grandfather, over the phone, because she knew he had been a migrant worker in the past. It turns out her grandpa was in the Bracero Program. This young lady had the presence of mind to record her conversation with her grandfather, who was so impressed and happy to share his story. When Abby brought her phone to school and played the interview for the class, they were spellbound. We are working on a transcript of the interview, as well as a sound recording.