Tuesday 22 March 2010 - Oxford Medical School Gazette

advertisement

Oxford Medical School Gazette

Volume 60(2)

Below is the full text of OMSG 60(2), with references.

For the full pdf file please visit: http://www.omsg-online.com/current-edition/

For other archive editions, further information about the Gazette, to download a subscription form

or to contact us, please visit: http://www.omsg-online.com/

Begins overleaf

Editorial

Welcome to the latest issue of the Oxford Medical School Gazette. The theme for this issue is

‘Stranger than Fiction’. This was chosen with the aim of inspiring our writers to explore the weird

and wonderful side of medicine, whilst still encouraging a wide variety of articles. They have not

disappointed us. Jonathon Best sets off to explore bizarre culture-bound syndromes from around

the globe (page 38), Benjamin Stewart delves into medical advances from the world of science

fiction (page 55), and Chris Deutsch discovers ‘penis captivus’: a condition direct from Oxford’s

greatest practical joker (page 51). On a rather different note, Annabel Christian investigates the

medicolegal angle of those who become murderers while they sleep (page 43), Charlotte Skinner

investigates the draw of the criminally insane (page 40).

Moving away from the theme, there are a variety of other articles to peruse and ponder. Roughly

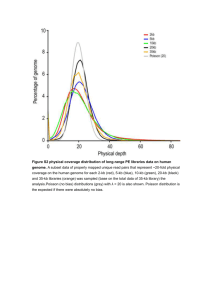

a decade since they began, Benjamin Stewart takes stock of the various genome projects and

examines whether the vast amount of data harvested will deliver on the promises made (page 30).

Elizabeth Anscombe reports from the front line of cancer research, focussing on recent advances

and personalized therapy (page 34) and Matt Harris illustrates the power of non-verbal

communication in clinical practice (page 8). Looking to the past, Charis Demetriou takes a scenic

tour through 700 years of medicine in Oxford, visiting various landmarks around the city and

uncovering their secrets (page 52).

Staying with the focus close to home, Sophie James highlights the creation of the new Osler

House (page 72), while Jack Pottle reports on paediatric cardiac surgery at the John Radcliffe and

its implications for surgical training (page 6).

Regular readers of the Gazette will also notice the inclusion of a brand new peer review section in

this issue (page 62). This section showcases original research from medical schools across the

UK, giving students the opportunity to get their feet on the rungs of academic medical ladder.

From over forty submissions, we present two papers in this edition from the world of obstetrics

and gynaecology, focusing on endometrial cancer imaging and pre-eclampsia genetics

respectively. All papers published are reviewed by academics and senior clinicians in the relevant

area, and this is the standard we are looking to maintain. We hope the peer review section will

continue in future years, with a view to encouraging proactive research, both clinical and

laboratory-based, throughout UK medical schools. The Gazette is therefore not only the world’s

oldest medical school publication, but also the UK’s only peer reviewed medical student journal!

As the year draws to a close, our time as Gazette editors has come to an end, but we hope that our

successors will continue what we have begun. We have thoroughly enjoyed our time working on

the Gazette and would like to thank the medical school for providing us with the opportunity to

do so. Most importantly, we hope that you have enjoyed reading the last few editions of the

Gazette and trust you will continue to do so for many years to come.

The OMSG editors,

Jack Pottle

Matt Harris

Namrata Turaga

November 2010

Contents

Letters

3

Practice

Too good to be true? - Fraud in medical research

4

“Thrive or perish” - Mentoring and paediatric cardiac surgery at the John Radcliffe

6

Communication on the front line - Why GPs make the difference

8

An epitaph for eponyms - How to get an eponymous syndrome

10

“Push harder you silly woman!” - O&G in Karachi

12

Comment

What if everything you though you knew about AIDS was wrong?

15

For love or money - Prostitution and the law in the UK

18

Evidence-based resurrection - The truth behind religion

21

Review

Neuroethics and oxytocin - Professor J. Giordano discusses love and drugs

24

Maternal mortality - Have the Millennium Development Goals delivered for women?

27

Deciphering our genetic code - The history of the Human Genome Project

30

The enemy within - Current progress in cancer therapeutics

34

Frith Photography Prize

36

Spotlight

Culture-bound syndromes - Bizarre disorders from around the globe

38

Dangerous liaisons - Why women can’t resist the criminally insane

40

Sleep killing - Homicidal somnambulism and the parasomnias

43

Synaesthesia - The human cost of merging the senses

46

The colour blind doctor - I see trees of red, green roses too...

49

Timeline

Penis captivus - ...and other tales from Egerton Y. Davis

51

The creation of Oxford medicine - 700 years on the streets of Oxford

52

Science fiction medicine - The fate of inventions from the movies

55

Ondine’s curse - The story of congenital central hypoventilation syndrome

58

Peer Review

Placental gene expression, pre-eclampsia and growth restriction

62

3-D transvaginal ultrasound in endometrial cancer

66

Obituary

Dr Klaus Schiller

70

Back Pages

Osler Report 2010 - A year in Osler House

72

Tingewick Archives - An interview with outgoing Tingewick patron David Messer

74

Book reviews

76

Emergencies: Labour - How to deliver a baby. In an aeroplane.

77

Crossword

78

Medical records - Some of the strangest world records ever to have been broken

79

Letters to the editors

Re: Healthcare under siege, OMSG 60 (1)

Dear Editors,

It is a pity that such a politically biassed article as that by Messrs Abdel-Mannan and Mahmud

should appear under the imprimatur of an organ of the University of Oxford. To describe the

plight of the Gazans as a consequence of “collective punishment” by Israel is a travesty of the

facts.

Hamas are dedicated to the genocidal destruction of Israel and to this end have waged war from

within, and at great cost to, their own civilian population showering rockets and missiles on the

people of Israel. As an Islamist movement supported by Iran they are not at all interested in a

secular state of Palestine and killed 350 of their Fatah compatriots in their bloody takeover in

2007. The contrast of Gaza with the increasingly prosperous West Bank is something the authors

might perhaps have addressed. Thanks to the reduction in terrorism and violence due to Israel’s

security fence and coordination with better trained security forces of the Palestinian Authority,

there was in the West Bank in 2009, an increase of 8.5% in the GDP (it was only 1% up in Gaza)

and a 9% reduction in unemployment and this at a time of world economic recession.

The authors pay some lip service to the need for the Palestinians to get their house in order.

Unhappily for the Gazans, the Hamas agenda gives priority to the removal of Jews from “Muslim

lands” and to Islamic conquest. Their murder of four Israelis with the stated intention of derailing the face-to-face peace talks between the two sides says it all.

Yours sincerely,

Dr Barry Hoffbrand

Queen’s 1952

Right of reply from the authors

Dear Editors,

Dr Hoffbrand’s response is a typical example of the factual inadequacy of many of Israel’s

staunchest supporters. Despite what he might like to imply, the international community is

unanimous in its agreement that Israel’s flagrant and collective punishment of Gazans is illegal,

and nothing less.

We refer Dr Hoffbrand to institutions not in the business of fiction, namely the International

Committee of the Red Cross, Amnesty International and the United Nations. Their statements can

be found online [1-3]. If Dr Hoffbrand would like to take his complaint to these organisations, we

would be most eager to hear their responses.

Despite his enthusiasm, Dr Hoffbrand hasn’t engaged with any of the medical issues outlined in

our article, which has deliberately avoided partisanship and political leaning (for example, the

simple observation that Israel has had more than 220 UN resolutions condemning its abuse of its

neighbours). Rather than dealing with the ethical and legal implications of documented White

Phosphorous burns inflicted by the IDF on masses of civilians [4], Dr Hoffbrand has attempted to

undermine honest discussion of the human rights violations of Palestinians by portraying their

struggle as a religious crusade; a great disservice to 60 years of Palestine’s struggle for selfdetermination.

We, as medical students and future doctors, must be guided by intellectual honesty, and

compassion in the face of human suffering. In this vein, we commend the work of Physicians for

Human Rights – Israel, and refer our readership to their detailed reports on Gazan health

(www.phr.org.il) and Israel’s ongoing siege.We trust our readers will appreciate the facts for

what they are.

Sincerely,

Imran Mahmud and Omar Abdel-Mannan

References

1. International Committee of the Red Cross:

http://www.icrc.org/web/eng/siteeng0.nsf/htmlall/palestine-update-140610

2. United Nations:

http://www.unhchr.ch/huricane/huricane.nsf/0/9B63490FFCBE44E5C1257632004EA67B?opend

ocument

3. Amnesty International: Amnesty International:

http://www.amnesty.org/en/news-and-updates/suffocating-gaza-israeli-blockades-effectspalestinians-2010-06-01

4. The Lancet, White Phosphorous burns:

http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(10)608124/fulltext?version=printerFriendly

The editors will not be publishing any further correspondence on this topic.

Too good to be true?

Mary Denholm examines fraud in medical research

At the end of 2004 everything seemed to be working out perfectly for Korean stem cell researcher

Woo Suk Hwang. Named one of Time magazine’s ‘People Who Mattered 2004’, the magazine

described how he had proved that “human cloning is no longer science fiction, but a fact of life.”

[1] Earlier that year he had published a landmark paper in Science describing the successful

creation of human embryonic stem cells using somatic cells and eggs from a single female donor.

Another apparently incredible piece of research appeared in Science in June 2005, when he again

claimed to have created human embryonic stem cells, but this time using only human somatic

cells. Unfortunately for him, and for stem cell research, things began to unravel four months later

when he was accused of unethical conduct in sourcing his donor eggs. Buoyed for a while by his

enormous public support in Korea where he was a national hero, things ultimately came to a head

early in 2006 when Seoul University announced that all eleven of his stem cell lines, and both his

iconic papers, were completely fabricated. His papers were unconditionally retracted and the stem

cell world was left reeling, with the resulting paranoia about validity and reproducibility still felt

today, creating an air of pessimism and scepticism in an exciting field of research.

With stories such as Hwang’s and the saga surrounding MMR researcher Andrew Wakefield

receiving widespread media coverage, it could be tempting to think that these are isolated

incidents: freak happenings in unfortunately high-profile areas of research. Worryingly however,

this seems not to be the case [2]. A meta-analysis by Fanelli [3] reviewed the results of 18

surveys of scientists and medical professionals involved in research and, of 12,000 subjects,

found that approximately 15% knew of someone who had falsified, fabricated or altered data,

with 2% admitting they had done so themselves. Unfortunately, similar findings have been

reproduced several times in other surveys [4]. It seems those cases exposed are just the tip of the

iceberg; an uncomfortable idea for the scientific community [5] which relies heavily on trust.

But how do we know what is fraudulent or unethical, and what if you accuse the wrong person?

There are also notable instances of the latter, shattering research programmes and careers. At the

end of the 1990s, a clinical trial in Stoke-on–Trent was examining the role of continuous negative

extrathoracic pressure (CNEP) in paediatric respiratory support. The parents of one child in the

trial accused the researchers of misconduct and there followed a prolonged set of investigations

by several NHS bodies, the GMC and an official government report. Over ten years later, it was

concluded that the defendants in fact had no case to answer, the trial was in no way unethical and

the government report itself was flawed. However, this was too little, too late for the defendants

as the case against them had been spread throughout the media, accusing the trial of “killing

premature babies” and the researchers of offences including forging consent forms [6].

Even several years before the case of Hwang and the eventual resolution of the CNEP incident, it

was plain that better regulation of research was needed, not only to identify cases of fraud but to

make the process of flagging up concerns fair and structured. In 1997 the Committee on

Publication Ethics (COPE) was created by editors of several British journals with the intention of

providing advice to editors on dealing with suspected fraud and producing guidance on proper

and ethical practice. Its formation was particularly timely due to a scandal the previous year,

whereby two eminent London consultants, Malcolm Pearce and Geoffrey Chamberlain, produced

a case report detailing the successful reimplantation of an ectopic pregnancy with a resulting live

birth. Later exposed as totally fabricated, the subject of the case report being fictional, their

careers were ruined despite Chamberlain’s insistence that he hadn’t known what was in the report

despite his name being on it, so-called ‘gift authorship’.

COPE aims to target all forms of fraud, whether the more overt cases such as fabrications and

falsification or slightly ‘greyer’ issues such as gift authorship and authorship disputes. Whilst

COPE’s work is clearly thorough and their website full of clear and constructive algorithms for

spotting and dealing with possible fraud, it is largely aimed at journal editors. The first person to

ring the alarm bells in the case of Pearce and Chamberlain was a junior doctor, but as we all

know, standing up and pointing out flaws is often easier said than done. However, many of us

have been or will be involved in research either as medical students or in our future careers, so

what should we do if we suspect something is amiss? The National Academy of Sciences has

published a guide entitled On Being a Scientist, which contains helpful advice on many potential

hurdles, including choosing research groups, research on students, and ideas for how to deal with

any suspicions you may have. It also succinctly describes the principles of staying on the right

road, reminding us of the obligations of any researcher “....toward other researchers, toward

oneself, and toward the public…” [7].

For any potential project, check the background to the research and any work done before your

involvement. Is ethical approval needed and has it been obtained from the appropriate university

or regional committee? If you are unsure at any point, try to raise any doubts you have and don’t

be afraid to ask for help or advice from external sources, even if it’s simply for your own peace of

mind in the end. It might not be all bad news for those above either, with some observers

suggesting that tackling internal fraud can actually boost an institution’s reputation, despite the

initial headaches and embarrassment [8].

By bearing these principles in mind we can hope to maintain our share of the trust on which the

scientific research community relies.

Mary Denholm is a final year medical student at Jesus College

The author would like to thank Professor Margaret Rees, Linda Gough and COPE for their

encouragement in writing this article.

References

1. TIME magazine: People Who Mattered 2004 - Dr Hwang Woo Suk. 2004 [cited 2010];

Available from:

http://www.time.com/time/asia/2004/personoftheyear/people/hwang_woo_suk.html.

2. Moore R, Derry S, McQuay H. Fraud or flawed: adverse impact of fabricated or poor quality

research. Anaesthesia. 2010 Apr;65(4):327-30.

3. Fanelli D. How many scientists fabricate and falsify research? A systematic review and metaanalysis of survey data. PLoS One. 2009;4(5):e5738.

4. Titus S, Wells J, Rhoades L. Repairing research integrity. Nature. 2008 Jun;453(7198):980-2.

5. Solutions, not scapegoats. Nature. 2008 Jun;453(7198):957.

6. Hey E, Chalmers I. Mis-investigating alleged research misconduct can cause widespread,

unpredictable damage. J R Soc Med. 2010 Apr;103(4):133-8.

7. Committee on Science Engineering and Public Policy. On Being a Scientist - A guide to

responsible conduct in research. 3rd edition ed. USA: National Academy of Sciences; 2009.

8. Misconduct? It's all academic... Nature. 2007 Jan;445(7125):240-1.

“Thrive or perish”

What’s wrong with surgical training?

The concept of the surgical learning curve is not a new one. As a surgeon enters their trade, their

skills are minimal - they may know the theory but the practice is quite different. Because of this,

their surgical outcomes will (all things being equal) be worse than those of a more experienced

surgeon. As the surgeon progresses, he learns from his mistakes, becomes more proficient, and

the curve levels off. This curve is often taken as a necessary evil; every surgeon has to perform a

procedure for the first time. However, in the current era of transparency and patient choice, the

public tolerance of this learning curve has understandably diminished. I for one would rather have

my child’s surgery performed by a consultant than a registrar.

It has therefore become imperative to minimise the surgical learning curve. Indeed, there should

be “no learning curve as far as patient safety is concerned” [1]. The two key angles from which to

tackle this problem are training and mentoring. Training implies active teaching on surgical

techniques, both on-the-job and in theory, and covers the use of laparoscopic training, cadaveric

dissection and many other widely practiced methods [2]. Mentoring, however, goes much deeper.

It carries the implication of a relationship; the mentor and the mentee must work together to help

develop the mentee’s potential. It also involves trust between the two parties – the trust that

support will be provided where it is needed but that independence will still be encouraged.

Mentoring is repeatedly identified as the key to improving surgical learning. However, it is a

scarce commodity in surgical fields [3]. Why is this? Perhaps, as can be seen from the above

description, it is because mentoring is a rather fluffy concept. Surgeons generally don’t like fluffy

concepts. This is never truer than in paediatric cardiac surgery, where the technical challenges

and high-stakes outcomes tend to attract individuals who have intense self-belief and will not

stand for anything less than perfection. This selection bias is, in a way, ideal, as it creates

technically excellent surgeons. It is not, however, necessarily the person who would want to put

in “time, patience, dedication and selflessness” to “foster and encourage independence” in a

mentee [4, 5]. The selection bias of the infinitely capable and self-confident surgeon also creates

problems from the other end: surgical trainees might not feel they need a mentor, let alone want

to be a mentor themselves. However, it is exactly this mismatch between confidence and

competence which is truly dangerous; as surgeons work outside their capabilities and without

appropriate support, mistakes increase.

Therefore there remains an “absolute apathy” towards mentoring in surgical circles, particularly

higher up the surgical ladder [3]. On asking one senior consultant about the role of mentoring, I

was told that there was no place for “hand-holding” in surgery, that all a surgeon needs is

experience, and that surgical training is simple: “you thrive or perish”. This viewpoint, which I

imagine is not an isolated one among consultants, reflects a gross misunderstanding of

mentorship. It also jeopardises the whole of surgical training and is, in a large part, responsible

for the fact that surgical trainees often feel let-down and isolated in their posts [3].

Perhaps it could be argued that the higher one rises up the surgical hierarchy – or medical

hierarchy for that matter – the less one needs support and mentorship. Perhaps that is what the

senior consultant quoted above meant. However, in the current era of lifelong learning and the

fact that surgeons in particular need to adapt to new techniques, those at all levels should feel they

have a mentor. As Professor Edward Baker, ORH Medical Director, notes: “Mentorship is a very

important method for professional development at many different stages in many different

careers.” In addition, although the concept of formal mentorship is a relatively new one,

“Insightful doctors have always sought informal mentorship in the past and experienced doctors

have been willing to offer it” [7]. While invaluable, the trouble with this informal mentorship is

that some people will inevitably slip through the gaps. Without a formalised mentorship

programme in training, there will always be occasions where surgeons find themselves alone and

unsupported.

The lack of support for surgeons – even those at consultant level – was illustrated by a report

earlier this year into the John Radcliffe’s paediatric cardiac surgery unit (see box 1, below). The

report levelled particular criticism at support and mentoring in the department and recommended

that the unit remain closed until practice is changed substantially [8]. The impact of a lack of

mentorship on clinical practice is therefore clear.

It is true, however, that experience is the key to learning. If we see surgery as a trade then surgical

training is essentially an apprenticeship - a word synonymous with experience. Unfortunately,

surgical training is not as simple as this. The European Working Time Directive limits hours in

theatre, the demand for higher theatre throughput limits time on each case, and the lack of

tolerance of mistakes discourages consultants from allowing their junior colleagues to operate on

their patients. As such, junior surgeons no longer have the freedom to gain experience where and

how they want it.

And it is this point, that surgery is not like it used to be, that seems to have been missed by some

surgeons and that fosters the misunderstanding about mentoring. When the current senior

consultants were on the way up the ladder, training was very different. Surgeons learned as they

went along, often teaching themselves in an environment where the training and support

structures of today were non-existent. What needs to be understood, however, is that that era is

over. Mentoring, be it structured or simply the knowledge that there is a colleague you can

discuss a case with outside the hospital, is vital to developing trainees. As Mr Ashok Handa,

Oxford’s director of surgical training, points out: “We’re here for patients, to deliver the best

possible care as safely and efficiently as possible. If that means we’ve got to work and be trained

in a slightly different way to continue our lifelong learning then so be it. Mentoring is a key part

of that.” [6]

If this message fails to get through, and consultants stick to the “thrive or perish” philosophy, the

development of surgical trainees is in trouble and ultimately it is our patients who will suffer.

Jack Pottle is a final year graduate-entry medical student at Magdalen College

Box 1: The demise of paediatric cardiac surgery at the John Radcliffe

In July 2010 an independent review, commissioned by the South Central Strategic Health

Authority, recommended that: “Paediatric cardiac surgery remain suspended in Oxford

until or unless the service can safely be expanded”.

This review followed four postoperative paediatric deaths between 22 December 2009

and 18 February 2010, a mortality rate 4.8 times higher than the national average

(p=0.012). The story was widely covered in the national media.

One newly appointed consultant surgeon was operating, without senior assistance, in all

of the cases. He ceased operating of his own accord following the fourth death. Oxford

then suspended its paediatric cardiac surgery service and a serious untoward incident was

declared.

The surgeon in question noted that he had experienced difficulties which “had surprised

him and the cause of which he could not explain”, though the review concluded that there

were “no errors in judgement directly leading to any of the deaths”.

The review identified various root problems, including that the new surgeon “would have

benefited from help or mentoring from a more experienced surgeon”.

The review panel’s report made 16 recommendations. Regarding mentoring, they

recommended that “all newly appointed consultant staff have access to an appropriate

mentoring arrangement”. In the case of paediatric cardiac surgery, they stated that this

“must include arrangements that facilitate joint operating”.

In October 2010 the NHS Safe and Sustainable review team recommended that Oxford

should not be considered as a possible centre for children’s heart surgery when a

consultation takes place in January.

The Oxford paediatric cardiac surgery unit is therefore likely to remain closed for the

foreseeable future.

The full report can be accessed at:

www.southcentral.nhs.uk/document_store/12804012741_orh_paediatric_review.pdf

References

1. Senate of Surgery: Response to the General Medical Council determination on the Bristol case,

1998, Senate of Surgery: London.

2. Hasan, A., M. Pozzi, and J.R. Hamilton, New surgical procedures: can we minimise the

learning curve? BMJ, 2000. 320(7228): p. 171-3.

3. Memon, B. and M.A. Memon, Mentoring and surgical training: a time for reflection! Adv

Health Sci Educ Theory Pract, 2009.

4. Cohen, M.S., et al., Mentorship, learning curves, and balance. Cardiol Young, 2007. 17 Suppl

2: p. 164-74.

5. Macafee, D.G., B. Mentoring and coaching: what's the difference? BMJ Careers 2010

07/10/2010 [cited 2010 07/10].

6. Handa, A., Personal communication: interview regarding surgical mentorship, J. Pottle,

Editor. 2010.

7. Baker, E., Personal communication: e-mail to Oxford Medical School Gazette, J. Pottle,

Editor. 2010.

8. Kirkup, B., Review of paediatric cardiac surgery services at Oxford Radcliffe Hospitals NHS

Trust, as commissioned by the South Central Strategic Health Authority. 2010.

Communication on the front line

It’s not just what you say or how you say it

As medical students, it’s not uncommon to be approached by friends and family for advice about

medical problems. Often it’s something completely benign, such as low back pain without the red

flags, and we can feel confident enough to reassure. Occasionally however, it may be something

potentially sinister, with cancer on the differential. This is a situation I found myself in recently

when a relative told me that she had recently experienced some post-menopausal bleeding

(PMB). Those who have done Obstetrics and Gynaecology will know that PMB is endometrial

carcinoma until proven otherwise and must be referred urgently for an ultrasound scan within two

weeks.

I suddenly found myself in very unpleasant and unfamiliar territory. As a relative, I was gripped

with numerous fears. What if this was cancer? What would happen to them? What if they died?

What would I do without them? But equally, I was very aware that as a medical student, this

relative was looking to me for reassurance and that any trace of worry or concern on my face

would be very obvious and unsettling to them. Despite my concern, I found myself slipping into

medical student mode: putting on a brave face, saying reassuring things and racking my brains for

the PMB differential so I could say something like “It’s probably just polyps”. I began to cobble

together something that resembled a gynae history, which, given the patient, was a rather

awkward task, and it became apparent that there had been two episodes of light PMB, or

‘spotting’. In addition, and more worryingly, there was continual pain on the right hand side

where the perineum meets the top of the lower thigh.

I asked my relative if she had been to see her GP and it turned out that she had been three times.

On the first occasion, she was examined, reassured and sent home with the usual safety-netting of

“Come back if it doesn’t get better or if it gets worse”. I found this somewhat unsettling given the

guidelines on PMB mentioned above, but put this down to the light nature of the bleeding. On the

second occasion, two months later, she mentioned that the pain had become worse. The GP froze

with a look of dread across her face. “Well I’m not even going to examine you this time, I’ll just

refer you urgently” she said. My relative knew immediately exactly what she was thinking: “It’s

cancer”.

The first problem here is that, having been reassured on the previous occasion, to be given an

urgent referral suddenly is rather alarming. The second problem here is the lack of examination. I

agree that examining the patient is not going to change the management: she will still be referred.

But assuming that there would be no abnormalities detected, this would be a great comfort to the

patient during her two week wait, especially after being given the impression that she has cancer.

In failing to examine the patient, the GP missed a valuable opportunity to reassure her. The third

problem here is how transparent the GP’s look of horror was. I imagine she was thinking “PMB

plus pain: it must be a gynaecological malignancy”. I agree that it should be on the differential

and that it must be referred in order to rule it out, but there are many things that could present in

this way. They may even be two independent problems. Assuming that it is cancer is jumping to

conclusions. Giving your patient that impression is disgraceful.

On the third occasion, the following week, my relative returned because she had questions that

she was in too much shock to ask about on the previous occasion; questions she had been

worrying about for the preceding week. “I’m quite worried”, she said nervously, hoping for

reassurance. The GP replied: “You’ve got every reason to be worried”.

Surely she didn’t mean that? Perhaps she meant “You’ve got every right to be worried”, still quite

an unsettling response. Personally I would have gone for “It’s natural to be concerned”. But to

say “You’ve got every reason to be worried” implies that the patient’s concerns are justified and

the diagnosis is in no doubt.

Fortunately I was on leave at the time of her outpatient appointment. I was able to go with my

relative and reassure her. When the radiographer announced that the endometrial lining was of

normal thickness I breathed a massive sigh of relief. In fact, I think my relative was slightly

surprised by the extent of my relief; my brave face must be very convincing! At this point,

standard procedure is to discharge the patient back to their GP for debriefing. I suspected that this

would be inviting yet more trouble so I piped up and asked if she could go on to the outpatient

appointment anyway, just to talk things through. The radiographer, looking slightly taken aback,

and, probably wondering what the hell I was doing in the examination room anyway, replied

“Erm, yes, I should think that’ll be alright”. After speaking to a specialist nurse, my relative left

feeling relieved and reassured.

I’d like to make it clear that this article is not in any way about GP-bashing, although I can

appreciate that it may come across in that way. I have no interest in GP-bashing – I myself would

like to become a GP one day. The healthcare professional in this article could have come from

any specialty. What I want to get across is the importance of good communication skills. We are

all taught about it at medical school. We attend classes where we cover various issues through

role-play with actors whilst our colleagues watch. But these scenarios will always be rather

artificial. It is only in the real world, where bad communication has real consequences, that the

importance of good communication becomes apparent. Communication takes place both verbally

and visually, and can be incredibly subtle. The GP in this tale made errors in both of these

departments. So when a patient presents with worrying symptoms, don’t jump to any conclusions,

think about what you’re going to say, give them the facts, and don’t let your inner concern show

on your face.

Matt Harris is a final year graduate-entry medical student at Magdalen College

An epitaph for eponyms?

Or, how to have your disease and name it too

Wouldn’t it be great to have a disease named after you? To go down in the literature as one of the

great doctors of all time, to be remembered alongside such greats as Alzheimer, Bell, Osler (and

Lou Gehrig)? Apart from the forgotten issue that it tends to mean your name will be forever

associated with pain (I don’t particularly envy Huntington – can my disease be mild, interesting

and completely curable, please?) there are no drawbacks. But how to get a disease named after

oneself?

Turns out, people are pretty flexible on naming diseases. It ends up just being whatever catches

on. Every few years the debate seems to flare up again – should we only have more descriptive

terms? Is it wrong to remember Nazis through disease names? The opponents of eponyms would

say yes; syndromes such as Reiter’s, Wegener’s and perhaps most famously Hallervorden-Spatz

(which you’ll all know, of course) are tainted with the blood of thousands. Hallervorden and

Spatz actively encouraged preservation of specimens from the gas chambers on the basis that they

were going to die anyway and it seemed a shame to waste such a valuable resource. When you

tell someone they have a disease, some would argue having it named after a war criminal makes it

worse, but is this actually what they think about when they are diagnosed? It is surely more to do

with the standing of the person honoured with a disease name; they become a medical great as

soon as they appear on whonamedit.com. And we want to keep the riff-raff, and the Nazis, out of

this club.

So, to be on the safe side, in our quest for an eponym, perhaps avoid war crimes. How else might

we increase our chances? It seems the next step is to find yourself a good teacher. It is never too

early to be eponymised. Our friend Huntington achieved international recognition with his

description of the disease at the tender age of 22 (although it had been described in Norwegian

twelve years earlier – but Lund’s disease doesn’t have the same ring to it), and studying under a

great will help you out no end. Consider the mega-celebrity Charcot; eponyms coming out of his

ears, including an island, which few doctors can boast. But he was as generous as he was utterly

egotistical, hence our knowledge of his students: a young Babinski, Freud, Gilles de la Tourette,

who after years and thousands of pages written on hysteria had a tic disease named after him that

he had written one article on. Still, fame is fame. Also, our favourite German, von

Recklinghausen, was a student of the great Virchow (he of the node) and consequently, despite

contributing next to nothing (two case reports, not the first, not all the clinical features), managed

to bag himself rather a tidy eponym. So snuggle up to Lancaster and Handa, the modern greats –

who knows what tasty little vascular abnormality might be tossed your way?

The other option, of course, is to be famous yourself. Big dogs such as Charcot could afford to

chuck the odd inconsequential disease down the ladder because they were just so stupidly wellknown anyway. Our own great physician, Thomas Sydenham, gave an incomplete description of

childhood chorea, as well as describing rheumatic fever, but failed to link the two and kept the

name anyway.

Of course, there is the proper way – years of hard graft, slowly collecting cases until finally

putting the pieces together in the manner of the Hollywood film. Arvid Lindau spent many a year

patiently collecting cases of cerebellar and retinal haemangioblastomas associated with cysts and

tumours of the pancreas, adrenals and kidney, and now, of course, he is more famous than God

(who incidentally is yet to have a disease named after him). But it is so much quicker to nick

someone else’s work, and we are after the quick fix (there is Huntington to compete with, after

all), and so maybe we can take a leaf out of the book of Johann Friedrich Horner, who dropped in,

had a quick look through his blurry eye and pulled together everyone else’s work on the

syndrome which then became his own.

Perhaps the quickest way, though, is to get the thing yourself. Admittedly this requires quite some

degree of luck, but there is always the satisfaction of guilt-tripping your excited neurologist into

letting you have the name. Julius Thomsen’s family, including himself, were affected by an

autosomal dominant disease causing myotonia and muscular hypertrophy and he described this in

1876; we now call this Thomsen’s disease. Every cloud.

Finally, if none of the above appeal, build yourself a great rivalry; I’m thinking Holmes-Moriarty,

Tom-Jerry, Lancaster-Handa. The greatest of these was, of course, between Josef Brudzinski and

Vladimir Kernig, both of whom claimed they had the most sensitive indicator for meningitis. To

this day, doctors all over the world pick a side. The battle outlived them both.

So you have your eponym. But what now? The naysayers want their more descriptive terms.

They want long, floridly scientific terms. Granted, they might be fairer, more easily classifiable

and more clinically useful (did you know that only 11% of orthopaedic surgeons could describe

Finkelstein’s test for tendovaginitis? Disgraceful!). But what of the history? What of the romance

of the men and – no, wait, just men, apparently – who toiled over their microscopes and

dissection tables? Are they to be swiftly forgotten? The glamour of medicine is fading fast, and

we cling to our last chance of fame. That is, before we switch to eponymous TV shows.

Tom Campion is a final year medical student at Wadham College

Push harder you silly woman!

State-run obstetrics and gynaecology in Karachi

In our fifth year, some of us are lucky enough to be able to do part of our Obstetrics and

Gynaecology (O&G) rotation abroad. Karachi, in Pakistan, doesn’t sound like an obvious

location for this. It’s a developing country lacking the ‘glamour’ of somewhere like South Africa,

the political situation is such that many people are afraid to leave their homes due to the very real

risk of bombings and, as an Islamic country, it’s not the ideal place for a male medical student to

learn about O&G! However, I had relatives to stay with and managed, very tenuously, to find a

gynaecology professor contact who reassured me that I would be able to fulfil most of my

objectives (mainly, delivering some babies!). She arranged for me to spend two weeks in Civil

Hospital in the centre of Karachi. Here is an abridged version of the blog I wrote while I was

there about a fascinating fortnight.

Tuesday 15 March 2010

Civil Hospital is government-funded, so treatment is free but resources are limited. The patients

are mainly from the rural suburbs and are very poor, badly educated and often illiterate. Many

women present for only the first or second time during pregnancy when they are in labour itself,

which impacts heavily on the pathology. For example, on my first ward round, I saw a lady who

was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes when she came in mid-labour and her baby (who weighed 5

kg) had severe shoulder dystocia and died before delivery.

The hospital itself is huge. In the main ‘courtyard’, there are loads of people wandering around,

some on stretchers or limping with dirty bandages towards A&E, plus the ubiquitous beggars and

vendors. There is a muggy smell as you enter the O&G Department, not helped by the forty

degree heat (there’s no air conditioning, just ceiling fans). I had extremely low expectations of its

general condition, having heard stories, for instance, about cats wandering around eating

placentas (which, apparently, doesn’t happen anymore!) but it isn’t too bad. The wards are basic,

containing simply lots of beds (ie an old mattress and sheet and a rusty bed frame), some of

which are shared between patients. Other than that, they are quite non-descript: dirty, cracked

white walls, no curtains and no electronic equipment.

Friday 18 March 2010

The labour ward floors are a grubby white with smashed tops of glass ampoules and dirt scattered

aroun. The twelve beds are arranged open-plan. They consist of two detachable parts, between

which is a metal bucket. The dirty black plastic ‘mattresses’ on the top half are covered by a grey

plastic sheet (I am unsure if these get changed) and the curtains are too small to serve any

purpose. When I saw a 22 year-old girl give birth yesterday, nurses were just walking past and the

other patients looked-on nervously, knowing that they would be going through the same ordeal

shortly. There are not enough anaesthetists to give epidurals either, so the ward is an unnerving

place to be when women are in labour! When everything had calmed down, the strategically

placed metal bucket was washed and put back. And the new mum finally showed some sort of

happiness at seeing her new baby boy!

Tuesday 22 March 2010

The operating theatres here are clearly different to the pristine ones we’re used to in the UK but

they weren’t terrible. There was an anaesthetics machine, the patient was draped and the surgeons

were gowned and gloved. It was only after the first operation that I realised the cloth drapes and

gowns are re-useable, as is the surgical equipment. However, instead of being irradiated, the

instruments are washed in the sink, while the green, blood-drenched cloth is rinsed and then

washed more rigorously outside and dried. All of this is finally sterilised in a rusty autoclave.

Similarly, ‘scrubbing in’ involves washing to the elbows with a bar of soap and tap water, before

putting on a gown and sterile gloves. Post-operative infection rates are apparently quite high. It’s

very easy to be really snobbish about all this, but I keep reminding myself of the money pumped

into the NHS that funds disposable equipment and that this sort of practice is completely

unfeasible here, where little money comes from a corrupt government and the patients can barely

afford the pennies to get the bus, let alone contribute to financing their care.

Saturday 26 March 2010

I actually felt quite sad during my last day yesterday, but there was a point on Thursday

afternoon, whilst standing at the foot of a Labour Room bed watching a doctor screaming at a

patient and preparing for another episiotomy, that I realised I’d had enough! The bursts of

positive emotion you might expect are also distinctly lacking, due to the very business-like,

unempathetic doctor-patient relationship and the mothers being simply relieved post-birth that the

pain is over.

Also, for many, this may be their fourth or fifth child born into poverty and clearly, especially in

the long-term, will represent a burden rather than a beacon of joy. This was exemplified by the

birth of quadruplets I saw on Thursday. Herds of journalists quickly descended upon the

delighted Labour Ward, as it was the hospital’s first quads that had all survived perinatally. But

during one of the interviews, the Head of Department walked past and pleaded that the patient’s

financial plight be highlighted during the news broadcast so she might get help from somewher;

she already had three young children and was clearly poor. It was quite disturbing seeing her

answer the reporter’s question: “Are you worried about having to care for four more children?” It

suddenly struck her that the coming years would be even more tough than the unimaginably

difficult conditions she was already experiencing.

Monday 28th March 2010

Finally, I just went to the private Aga Khan University Hospital (AKU), which is the country’s

top medical school. It is a huge complex of extremely well-maintained pink buildings, boasting

award-winning Islamic art and architecture, with beautiful lakes and flowers in the impressive

grounds. It’s pretty much the direct antithesis of Civil, which is only a few miles away. In

Pakistan, you can either afford to go private (£1000 gets you a private, en-suite delivery room), or

you end up in state care. The difference is inconceivably vast and patients who would be treated

using world-class techniques in AKU would simply be left to die in government hospitals.

The contrast between these two hospitals was a stark reminder of the chasm in Pakistan between

the very rich, with their Ferraris, and the extremely poor, where five year-old children beg at car

windows. Just yesterday, as I was giving gifts to the staff, one of the operating theatre technicians

pretty much begged me for 100 rupees (about a pound). After initially saying no, I gave him the

money I had, realising that even a few pounds might really help him out.

Reflections

So, it was an extremely interesting two weeks, both in terms of seeing Karachi itself and seeing

how a developing world state hospital, in a city with 19 million people, operates. Other than

performing one delivery and assisting in some Caesarian sections, I didn’t get to do much (no

gynaecology), but that was expected. I was the only male in the department, which made doing

anything very difficult – I was only allowed to do the delivery because the doctors felt sorry for

me! Nevertheless, the whole experience that was so incredibly intriguing that I have no regrets

whatsoever. It’s easy to criticise the lack of Labour Room privacy, infection control issues and

basic wards, but you soon recognise that limited funds mean the main aim is to safely manage

patients and that any ‘perks’ are a waste. The doctors – who, incidentally, work 36-hour shifts –

also describe how their medical acumen improves by having to diagnose most conditions

clinically, as investigations cost valuable money. In light of these obstacles, it’s incredibly

impressive that such a department can cope with thirty births each day, several Caesareans, and

the odd ruptured ectopic, neonatal resuscitation and eclamptic patient, plus elective surgery and

outpatients. It really opens your eyes to the challenges, and relative successes, of developing

world healthcare.

Aamir Saifuddin is a final year medical student at Exeter College

The author would like to thank Professor Ayesha Khan for her help in organising the placement.

What if everything you thought you knew

about AIDS was wrong?

Jack Carruthers examines the sinister ramifications of AIDS denialism

HIV does not cause AIDS. AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome) is a dustbin acronym

for any disease that can result from detrimental lifestyle choices, particularly the use of

intravenous drugs, poppers and AIDS medication, azodothymidine (AZT). These drugs assault

the immune system leading to an AIDS-related disease. But HIV (human immunodeficiency

virus) cannot do this. Brainwashed as we are by the HIV=AIDS=death paradigm, can we take a

step back and question this insidious implication?

Christine Maggiore did so. I read her polemic, What if everything you thought you knew about

AIDS was wrong? on the train from Oxford to London one January afternoon. Fellow passengers

regarded me with wary sympathy: “Poor boy. He has AIDS and he doesn’t even understand...” I

don’t have AIDS, actually. Nor do I have HIV. If I did, however, I can’t help but think I would be

seduced by Maggiore’s message that rips apart the causative link between HIV and AIDS [1].

And I’m a medical student with a reasonable grasp of the scientific process, and an education in

HIV/AIDS that indisputably links the two. For someone without this background, I can imagine

that some of the arguments put forward by AIDS denialists – as Maggiore and others who think

like her have been branded by the scientific community – would be more than compelling.

Maggiore’s position is concisely outlined in layman’s language without being patronising. She

notes that since Gallo’s discovery of HIV in 1984 “more than 100,000 papers have been

published on HIV” and that not one of them has “demonstrated that HIV can kill T cells” [1] [2].

According to Maggiore, twenty years of research into cancer retroviruses have conclusively

proven that retroviruses like HIV are not cytotoxic, and so cannot possibly deplete T cells to the

levels seen in AIDS patients. Tellingly, the paper published by Gallo after he announced to the

media during an international press conference that he had discovered the “probable cause of

AIDS”, failed to document the presence of “HIV (actual virus) in more than half of the AIDS

patients in his study” [1,3].

I was tempted to dismiss Maggiore as a delusional sensationalist until I found that the works of a

significant number of pre-eminent scientists were the rationale behind AIDS denialist philosophy.

Surely the most notorious is Peter Duesberg, a man (perhaps unfairly) rubbished by the scientific

community due to his controversial refutation of the HIV=AIDS=death paradigm. He is a

retrovirologist at Berkeley, University of California, and in 1987 published a paper demonstrating

that HIV is in fact harmless and that AIDS is caused by things like illicit drug use and, more

controversially, by AIDS medication such as AZT, a point to which I will return. The Nobel

prize-winning chemist, Kary Mullis, who developed the polymerase chain reaction, agrees with

Duesberg, claiming that there is “no scientific evidence” to show that HIV causes AIDS. Mullis

even writes the foreword to Maggiore’s book writing that she gives “the simple truth about

AIDS” [1]. Duesberg is no quack either. He rose to fame in the 1970s as the first man to

demonstrate the existence of retroviral oncogenes that could cause cancer in mammalian cells. He

later became a member of the prestigious National Academy of Sciences [4].

Since his espousal of AIDS denialism, Duesberg has become something of a pariah in scientific

circles. His laboratory is a barren shell of its former self, consisting of just Duesberg and a

graduate student, compared to its 1980s heyday of numerous graduate students and post-doctorate

researchers. He has had funding applications for even non-AIDS related research denied twenty

times [5]. Despite this, I felt that given Duesberg’s uncommon achievements in cancer research,

his views on AIDS cannot be summarily dismissed. Perhaps there is merit in claiming that drugs

and other lifestyle choices cause AIDS?

AZT is the bête noire of AIDS denialists, who claim that it is a sinister cause of AIDS foisted

upon us by greedy pharmaceutical companies. AZT carries a label dominated by a picture of a

skull and dire warnings in the case of accidental ingestion [6]. AZT was originally developed as a

cancer chemotherapy agent in the 1950s but was, according to Duesberg, withdrawn after mice

died in clinical trials from severe toxicity [7]. A nucleoside analogue, AZT works by terminating

DNA chains made by reverse transcriptase and is now almost always prescribed as part of highly

active anti-retroviral treatment (HAART) [8]. Duesberg attacked AZT, alleging that it is nonspecific to viral DNA. It kills human DNA as well and results in severe depletion of bone marrow

leading to immune deficiency or AIDS [9]. According to denialists, it causes the cytotoxicity

attributed to HIV infection. In addition to AZT, poppers (nitrite inhalants), heroin, and cocaine

are all cited by AIDS denialists, including Duesberg, as AIDS-causing. A Dutch study into

heroin-use and AIDS found just that. The group measured T-cell reactivity as a result of heroin

injections in both HIV-negative and HIV-positive individuals and found that T-cell reactivity was

negatively correlated with drug use. In other words, immunity was compromised by the use of

heroin. AIDS denialists claim that such conclusions are borne out in real life. It is no secret that

the gay community has suffered from the scourge of high AIDS-rates more than the straight one,

and this can be attributed, say denialists, to its use of recreational drugs, especially poppers [9].

I was disquieted by these denialist revelations among others. Had I unwittingly bought into a

medical conspiracy? Delve a little deeper, though, and you will find, as I did, that denialist

claims, while compelling in print, mask a multitude of sinister implications for real life. Therein

lies the danger. Indeed, AIDS denialism has been described by Warren Winkelstein Jr., a

Berkeley AIDS epidemiologist, as “irresponsible, with terribly serious consequences” [4]. I

would go one step further and say that denying the link between HIV and AIDS has such severe

ramifications for society that it is almost criminal.

Duesberg appears to have misunderstood the results of the Dutch study that he claims shows

heroin can cause AIDS. Whilst it is true that T-cell reactivity decreased in both HIV-negative and

HIV-positive patients, it is not true that the HIV-positive individuals developed AIDS as a result

of their drug use. Indeed, the HIV-positive patients had average T-cell counts well below the

clinically normal range of 600–1200, unlike the HIV-negative patients, suggesting that there was

already a decline in T-cell count due to HIV infection prior to the study [9].

The belief that drugs such as AZT can cause AIDS is dealt a further blow by evidence which

suggests that AZT helps to prolong life and reduce the number of AIDS-related diseases in the

first year after diagnosis with AIDS (not HIV). This was conclusively demonstrated in the

British-French Concorde study which involved 1,759 HIV-positive people [9]. Despite this, few

would argue that AZT is a wonder drug. As a result, it is now only prescribed as part of HAART

and is just one treatment weapon in a multi-pronged attack on HIV.

While it is true that scientific consensus has been unable to conclusively demonstrate how HIV

kills its target T cells, it is untrue (as Maggiore falsely alleges) that we have not come close. A

casual search of PubMed reveals many scientific papers that posit possible mechanisms whereby

HIV kills its target. These include over-accumulation of viral transcripts in the cells, in addition

to indirect autoimmune mechanisms and apoptosis in a kind of self-preserving attempt [10]. And

many of these papers were written before the 2000 edition of Maggiore’s book.

AIDS denialism is not confined to leprous pseudo-scientific back-rooms. It pervades society

today. Former president of South Africa Thabo Mbeki’s administration refused to implement an

overall national treatment programme for anti-retroviral medication in a country stricken by the

AIDS epidemic because it doubted the link between HIV and AIDS. Public health researchers

assert that the implementation of such AIDS denialism has contributed to 340,000 deaths from

AIDS in South Africa [11].

But what of Christine Maggiore? Her book is emblazoned with endorsements from various

notables. She writes clearly and intelligently – a message of hope. There are photos of her looking

pretty and healthy with her son. They seem to belie the fact that she was diagnosed with HIV in

1992 after a series of inconclusive tests for HIV – a factor which contributed to her growing

scepticism [1]. Maggiore held steadfastly to her beliefs despite constant criticism from the media,

the scientific establishment and AIDS activist groups. Indeed, her conviction was so strong that

she did not take antiretroviral medication during her second pregnancy. When her child, Eliza

Jane was born, she refused to test the baby for HIV and recognise the real risk that her daughter

had contracted the virus. On 16 May 2005, Eliza Jane collapsed and later died in hospital. Eliza

Jane was revealed by autopsy to be chronically under-weight and under-height. Her lungs were

infected with Pneumocystis jirovecii, an opportunistic pathogen and the leading cause of

paediatric AIDS-related deaths [12]. Maggiore herself died in 2008 from disseminated herpes

infection and oral candidiasis at the age of 52 [13]. I need not mention that these diseases are all

too common in HIV-positive AIDS patients.

It seems to me that Eliza Jane died because of her mother’s trenchant unwillingness to believe

that HIV causes AIDS. Even if this was not the case, and she did in fact die of a tragic case of

childhood pneumonia, Maggiore’s views are difficult to justify. Perhaps those who would agree

with AIDS denialists deserve our sympathy. They are liable to die earlier than they otherwise

would should they contract HIV and refuse to take medication. However, these people become

dangerous apologists for ignorance when their beliefs prevent others from receiving the education

and treatment for AIDS that they need. AIDS denialism has a human face and a human cost. For

that, AIDS denialists deserve not our sympathy but our strongest contempt.

Jack Carruthers is a third year medical student at St. Hilda’s College

References

[1]

Maggiore, C. What if everything you thought you knew about Aids was wrong? (4th ed.)

The American Foundation for AIDS Alternatives: Studio City, California, USA.

[2]

Altman, L. New York Times: April 1984.

[3]

Gallo, R. 4th May 1984. Science; 224: 502.

[4]

Cohen, Jon. The Duesberg Phenomenon. Science 9th December 1994; 266.

[5]

Lenzer, J. AIDS dissident seeks redemption...and a cure for cancer. Discover Magazine

15th May 2008. Available at: <http://discovermagazine.com/> [7th August 2010].

[6]

<http://www.google.co.uk/> Image result. Search: AZT.

[7]

Duesberg, P. Inventing the AIDS virus. Regenery Press: Washington DC, 309 – 359.

[8]

Mitsuya, H., Yarchoan, R., Broder, S. Molecular targets for AIDS therapy. Science; 249

(4976): 1533–44.

[9]

Cohen, Jon. Could drugs, rather than virus be the cause of AIDS? Science 9th December

1994; 266.

[10]

Finkel, T.H., Banda, N.K. Indirect mechanisms of HIV pathogenesis: how does HIV kill

T cells? Current Opinion in Immunology August 1994; 6(4): 605 – 15.

[11]

Chigwedere, P. et al. Estimating the Lost Benefits of Antiretroviral Drug Use in South

Africa. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes October 2008; 49: 410

[12]

HIV infection in infants and children. (July 2004) [Online]. Available at:

<http://www.thebody.com/> [8th August 2010].

[13]

[Online]. Available at: <http://www.Aidstruth.org/> [1st July – 31st August 2010].

For love or money

“You’ll never, ever make sex work disappear”, says Justin Gaffney, a consultant nurse in sexual

health who has specialised in providing healthcare for sex workers for over 16 years. However,

the Home Office continues to attempt the eradication of this so-called “informal economy”[1] the unregulated, untaxed industry which strives to remain invisible to the state.

New UK legislation to “tackle the demand for prostitution” came into force on 1 April 2010, as

part of the government’s Coordinated Prostitution Strategy. New ruling prohibits collaborative

prostitution, making brothels illegal, and criminalises the purchase of sex from those forced into

prostitution, using the chilling flagship slogan “Walk in a punter. Walk out a criminal.” [2] But

will the government’s new rules help the vulnerable people they wish to protect?

Between April and September 2009, Gaffney and his colleagues carried out a survey of male sex

workers. This not only challenged ingrained views of sex work as an exploitative, coercive

underworld of crime, drug addiction and social exclusion, but also highlighted the serious unmet

health needs of sex workers. For example, although the majority of the survey’s respondents were

engaged in sex work by choice, over two thirds of those working in the porn industry had

engaged in ‘bare-back porn’. They mistakenly believed that the production companies employing

them, despite being both independent and unregulated, were responsible for ensuring they were

protected against contracting HIV on-set. Although 85% of the men had undergone an HIV test,

the vast majority had little or no understanding of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) or how to

access it, correlating with a lack of contact with outreach health services [3].

Gaffney’s concerns are shared by colleagues working in parallel with female sex workers.

Andrea, a nurse who specialises in the sexual health of prostitutes, is worried about the risky sex

her clients are engaging in. “The sex industry is saturated at the moment”, she tells me, “The

market’s flooded by girls immigrating from overseas and the recession has also caused a drop in

custom. We find the girls offering increasingly risky sexual services, such as unprotected oral

sex, because it allows them to charge more money. We have to do a lot of work educating the

girls about contraception”. Aren’t drugs a problem in this population? “Drugs aren’t particularly

common amongst our patients” Andrea tells me, “you find the odd pocket of girls using crystal

meth to help them cope with long hours, but they usually avoid substances that affect their

judgement. One of our biggest problems is that a lot of our girls don’t have a valid immigration

status, so they’re afraid to access NHS healthcare services. A private abortion costs £500 with an

insecure income, and when supporting children and families back home, these girls haven’t got

that sort of money”.

The review used to back the UK’s new legislation boasts the use of research, audits and

ministerial visits to Europe to inform its recommendations. Of the 21 “stakeholders” listed as

participating in this research, none are actually sex workers, however, two thirds are members of

the UK Network of Sex Projects (UKNWSP), a non-profit, voluntary association of agencies and

individuals working with sex workers [4].

Unfortunately, the UKNWSP feel their views and experience have been disregarded and have

published a 26 page document detailing their dissatisfaction with the new legislation [5]. “Most

of the suggestions put forward by these projects were completely ignored, the Home Office

instead taking on board only recommendations from prohibition and abolitionist organisations

that see all sex work as violence against women and children.” Gaffney tells me. The UKNSWP

have observed that attempts to criminalise individuals involved in the sex industry erode the

probability that sex workers will be able to access social support and healthcare by driving sex

work further underground [5].

“It takes a lot of effort to reach the girls”, says Paz, an outreach worker at a sexual health and

social support practice in central London. “We have to work hard to gain their trust - even just to

make that first contact and give them some free condoms. It’s now illegal to advertise using

calling cards, and most girls use the internet to advertise so it becomes very difficult for us to

keep track of them. They move a lot and they’ll often put the phone down on you if they don’t

know who you are.”

The UKNSWP fear that the government has failed to address violence against sex workers and

improve their safety. The three Bradford murders reported in May this year exemplify the most

brutal examples of violence against prostitutes, but such tragedies are not the only danger a

prostitute faces. “Robberies are common” says Venetia, who runs a drop in health and social

clinic for female sex workers in central London, “Men will pose as clients but have a gang who

force entry to the flats when the girls open the door to them. The girls don’t understand that they

have the same rights to police protection as anybody else”.

Behaviour in the police force does not always serve to improve the relationship of sex workers

with the law. “Police will raid the working flats and take all the girls cash in the name of ‘seizing

the evidence’”, says Jane, who has coordinated a sex work project in London since the 1980s.

“The girls don’t stand up for themselves because they don’t know their rights. The

money can theoretically be reclaimed, but in reality ends up with the Inland Revenue.”

Venetia and others like her are also worried that new laws criminalising those who buy or profit

from sex compromise the girls’ safety: “Men buying sex obviously want to avoid prosecution, so

they’ll encourage women to go to more remote locations to provide services. Criminalising

brothels forces girls to work alone. This is very dangerous”. Venetia, like so many similar

organisations, runs an ‘ugly mugs’ scheme which allows women to anonymously report assaults

against them by so-called ‘dodgy punters’ which are then circulated to try and avoid similar

attacks on other sex workers.

But not all clients are violent, so who else is buying sex? Even the government can only provide

“suggested motivations” including “dissatisfaction with existing relationships”, “loneliness”,

“having no sexual outlet” and “curiosity” [6]. It seems there is no typical client. Consider Nick

Wallis, a young man born with the severely life limiting and disabling muscular dystrophy, who

lost his virginity to a prostitute at the age of 22. Previously feeling that he was living “an

existence, not a life”, Nick wanted to ensure he experienced “physical intimacy” before he died

[7]. His needs would be understood by Tender Loving Care (TLC), a trust that seeks to enable

professional sex workers to fulfil those who are “sexually dispossessed”. The TLC trust claim

that sex workers “rescue disabled people from personal anguish, sexual purgatory, and touch

deprivation” and that “two stigmatized groups provide each other with triumph: sexuallydeprived disabled people get laid, and sex workers gain a renewed pride in their work” [8].

The government’s own researchers have warned that the new legislation has already been shown

to be imperfect. In Sweden, following criminalisation of demand, the working conditions for

street workers appeared to deteriorate, and there was evidence of the market simply shifting

indoors [6]. Researchers also speculate that the low risk of arrest to an individual purchaser of

sexual services cannot act as an effective deterrent in reducing the demand for sexual services [6].

Of all the evidence they had analysed, the researchers stated that “methodological difficulties

plague research... There are many gaps in the research and much of the evidence is weak or

inconclusive” [6].

The UKNSWP has declared that concentrating on criminalisation rather than further investment

in support services for sex workers represents “extremely poor social care planning” [5]. They

believe that the government is failing to tackle the reasons people enter street work, and to

provide adequate specialist health services such as counselling and drug treatment services,

housing, and employment advice and training. “Women can become very institutionalised in sex

work and find it very difficult to leave” says Venetia, “They may ask us for guidance on finding

and training for another career. Interestingly they often seem to choose careers that share that

element of ‘love without consequence’: beauticians, hairdressers, pet-groomers, and that sort of

thing”.

Perhaps it is time the government listened to the prostitutes themselves. Sex worker Thierry

Schaffauser no longer wishes to be branded a public nuisance or spreader of disease. He writes

“The first step in the fight against “whorephobia” is to name the oppression… A further step

would be to fight the hate crimes sex workers suffer instead of criminalizing us” [9]. Perhaps the

hope for the future can be summed up by the tag line of the International Prostitute Collective:

“No bad women - just bad laws” [10].

Mary Keniger is a foundation doctor who graduated from Green-Templeton College in July 2010

References

1.

Day S. On the Game; Women and Sex work.

2.

Home

Office

Campaign

Poster.

Available

from:

http://toomuchtosayformyself.files.wordpress.com/2010/04/untitled.jpg?w=375&h=531

[Accessed 12th August 2010]

3.

Justin Gaffney, personal communication, June 2010.

4.

Home Office. Tackling the demand for prostitution: A review. November 2008.

Available: http://uknswp.org/resources/demandReport.pdf [accessed 24th June 2010]

5.

UKNSWP. Response to the Home Office “Tackling the demand for prostitution: A

review”. January 2009.

Available: http://uknswp.org/resources/demandResponse.pdf. UK Network of Sex Work Projects.

[accessed 24th June 2010]

6.

Wilcox A, Christmann K, Rogerson M, Birch P. Tackling the demand for prostitution: a

rapid evidence assessment of the published research literature. December 2009. Available:

http://rds.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs09/horr27c.pdf [accessed 24th June 2010]

7.

Wallis N. My Lifelong Desire. The Guardian 15th Jan 2007. Available:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2007/jan/15/health.socialcare [accessed 24th June 2010]

8.

TLC Trust [online]. Available from:

http://www.tlc-trust.org.uk/

9.

Schaffauser T. IN Whorephobia affects all women. (2010). Available:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2010/jun/23/sex-workers-whorephobia

10.

International

Prostitutes

Collective.

[Online].

Available

from:

http://www.allwomencount.net/EWC%20Sex%20Workers/SexWorkIndex.htm

Evidence-based faith: The Resurrection

In the era of evidence-based medicine, Hugh Gifford wonders if the

same approach will work for religion

The underlying principle of evidence-based practice is that we base our actions on what is true.

Scientific enquiry is powerful. The medical profession boasts confidence in drug therapy for this

reason. However, as evidenced in the recent case of rosiglitazone, our faith can be misplaced.

What we believe about whether or not drugs work must be based on evidence.

Similarly, proper investigation can shed light on religious matters too. The resurrection is a

suitable example. It is a concrete historical event: it either happened or it did not. It is also the

cornerstone of Christian faith: without it, “our preaching is useless and so is your faith” (St Paul).

As medical students, we are often living by faith as we trust in the literature. Here’s a question

regarding your personal faith in warfarin. I assume that you believe it is an anticoagulant that can

reduce the incidence of stroke in a population with atrial fibrillation (AF). Is your belief based on

what you have heard or read and not on what you have seen? We are “sure of what we hope for

and certain of what we do not see,” (St Paul’s definition of faith) – unless we see it with our own

eyes.

As a profession, we even exercise blind faith. A good example is the case of the diabetes drug

rosiglitazone, a product of GlaxoSmithKline. This expensive medication has already been taken

by millions of people but now appears to increase the risk of heart failure and myocardial

infarction. “Hailed as a much needed new approach for patients with type 2 diabetes, the drug

was licensed 10 years ago with only limited evidence of its effectiveness and concerns over its

safety” writes BMJ editor, Fiona Godlee. She suggests that “rosiglitazone should never have been

licensed and should now be withdrawn” [1].

There was once a junior doctor. He had learned about the use of warfarin in AF while he was at

medical school. But on his first night shift, alone at the Churchill, he struggled to prescribe it.

“Unless I see the original randomized controlled trials (RCTs), I won’t write it up!” On handing

over the undone job to his senior house officer (SHO), he blushed a little. The SHO had just been

writing their dissertation of the subject, and was able to show him five RCTs that demonstrated a

reduced incidence of stroke with warfarin. “Touch them!” said the SHO, “There’s even a

Cochrane Review.” He peered down at BAATAF, SPAF I and SPINAF, conducted in the US,

CAFA in Canada, and AFASAK I in Denmark, all during the late 1980s. Two thousand three

hundred and thirteen patients with AF, mean age 69 years, mean follow-up 1.5 years, were given

a vitamin K antagonist to various degrees compared to placebo and saw “about 25

strokes…prevented yearly per 1,000 participants” [2].

Some require real evidence to believe, while others are happy to assume there is evidence. A

member of the former party, like our skeptical doctor, was ‘doubting’ Thomas. He would not

believe his friends’ reports that Christ had risen from the dead. “Unless I see the nail marks in his

hands and put my finger where the nails were – and put my hand into his side – I won’t believe

it.” It was only a week later, when he actually saw Christ, that he believed it. Before I knew the

evidence for warfarin, my faith was blind, resting on the assumption that modern medical

consensus is established on evidence. Thankfully, it does have an evidence base, but does the

resurrection?

The Evidence

The hypothesis is that, long before the phrase ‘gospel truth’ entered our vocabulary, Christ died

on a cross on a Friday c. 34 AD and was alive by the Sunday. This is an event, not a repeatable

experience, so the normal testing via experiment won’t help. As the philosopher Gary Habermas

says: “We don’t see dinosaurs, we study the fossils. We may not know how a disease originates,

but we study its symptoms. Maybe no-one witnesses a crime, but police piece together the

evidence after the fact” [3]. James Cameron, director of Terminator, Titanic and Avatar, asks,

“How did these ideas take root? How did they ultimately transform western civilization?” [4].

Evidence in favour of a resurrection can be neatly organized into the following arguments:

The case reports are several, accordant, high in copy number and concordant with local

history

Their style and detail are consistent with their being eyewitness accounts

The narrative confirms Christ died physically