Notes submitted by Hackworth & Highlander

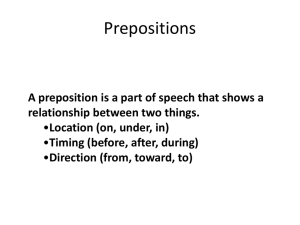

advertisement

Prepositions - Can have specifiers of prepositions. Right is a good test for prepositional phrases and can be called a specifier of a prepositional phrase. It can precede almost any prepositional phrase. Prepositions are very much like verbs. They take complements. They are sometimes transitive and other times intransitive like verbs are, e.g. I threw it out (the window) but I left it near the door/*I left it near. Locative prepositions are usually obligatorily transitive, and directional prepositions are usually optionally transitive. The preposition with can be instrumental/utilitarian and sometimes express manner. Accompaniment and instrumental uses of with are similar, but they are semantically distinct. In the example Come with, the context fills the gap syntactically and allows certain syntactic constraints to be overridden. This particular example is restricted to certain varieties of English, but it allows a lot that would not otherwise be allowed syntactically in English. Prepositions can take prepositional phrases as their complement, e.g. I left the ball near to the post. Certain prepositional phrases take different types of complements. For example, between takes conjoined complements i.e. x and y. The compound near death is likely a compound formed from the prepositional phrase and its complement. This particular compound, along with door stop, have the peculiar feature of taking its categorical identity from the right side rather than the left side. In English, the categorical identity almost always comes from the left-hand side of the phrase in phrase constructions. In other words, the head of the phrase appears to the left complement. The compound door stop probably came from door stopper. In fact, it is the exception to the observation that prefixes cannot change the lexical category of the word. As in, un-wrap, which remains a verb after prefixing for example. Word formation, particularly compounding, allows the head to be on the right side as in near death and door stop in English. In fact compounds get their identity from the right side in English. Phrase constructions tend to be more malleable than word formations. One may logically apply this concept to morphemes as in like-able, which takes its categorical identity from the right side. Words are not beads on a string. Words are strings made of strings made of strings, etc. Adjective order (in English) The order likely has something to do with semantic classes. Adjectives can be characterized: individual, stative, characteristic, how one is essentially, permanent, etc. Adjectives can be permanent or temporal, as in sickly versus sick. The progressive and perfective are the most common syntactic forms of aspect. “Aspect” is a fairly complicated term. Different types of aspect exist in many languages, and some do not mark it morphologically. One can differentiate between different forms of progressive and perfect by introducing tense, with six possible categories. Infinitives look different from language to language. Finiteness marked on a verb serves more to mark the clause as finite than the verb itself. Finiteness is a property of a clause. Analogy: How do you get Nouns to point to things? You quantify them - all blue chairs, the blue chair, a blue chair, this blue chair. Possessive determiners such as my, your, etc can also be used. This isolates an entity that fits said description, or points to the lack of existence of such an entity. Denotations of finite clauses: something in the world is denoted Ex: “Tyler is wearing a green shirt.” “It’s raining.” This refers to a state of affairs or event that can be verified as true or false. Every sentence that is an assertion is either true or false and can be checked. “Harry eat pizza” or “John be kind” There is no finiteness, so it cannot be checked to see if it is true or false. Be does not connect with reality. Finiteness anchors a sentence to a time, allowing it to contain truth or falsity Tense points to the content of a proposition and to a state of affairs in time, present, past or future, for us to check the truth of it. There are no connections between the phrases the meaning and the words without tense. Aspect can exist without tense, but without tense we have nothing to check. ex. “I must have been...” Have shows aspect, not tense here. English has a degraded agreement pattern. You can only tell if you use a 3sg subject in the present tense (ex. She eats), most of the time. An exception is I am, you are, he/she/it is, etc., but I ate, you ate, he/she/it ate, etc. Semantics “John ate apples” This phrase is in the past, but has no endpoint and is therefore atelic * “John ate 2 apples” This phrase is in the past and has an endpoint, so it is telic. Atelic means there is no endpoint, and telic means there is one. “John read Moby Dick” He has finished reading the book. This can be seen as a sequence of sub-events. Changes of state can be in increments as in “John read Moby Dick” or all at once as in “John hugged Susan”. Some verbs can bring things into or out of existence, while others rely and pre-existing things, i.e. “John built a house” vs. “John painted a house”. One can talk about the inner aspect of a phrase or sentence. There is a difference between sentence-level aspect and semantic aspect, but they are interrelated. Subordination English has a staircase-like structure, but not all languages do as exemplified by Japanese for example.