H.nana

advertisement

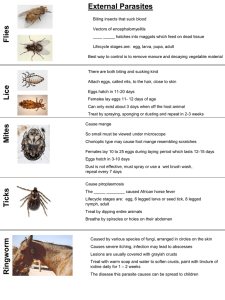

Submitted by Thikra Abdullah Mahmood Causal Agents of Hymenolepiasis : Hymenolepiasis is caused by two cestodes (tapeworm) species, Hymenolepis nana (the dwarf tapeworm, adults measuring 15 to 40 mm in length) and Hymenolepis dimnuta (rat tapeworm, adults measuring 20 to 60 cm in length). Hymenolepis diminuta is a cestode of rodents infrequently seen in humans and frequently found in rodents. Life Cycle: Eggs of Hymenolepis nana are immediately infective when passed with the stool and cannot survive more than 10 days in the external environment . When eggs are ingested by an arthropod intermediate host (various species of beetles and fleas may serve as intermediate hosts), they develop into cysticercoids, which can infect humans or rodents upon ingestion and develop into adults in the small intestine. A morphologically identical variant, H. nana var. fraterna, infects rodents and uses arthropods as intermediate hosts. When eggs are ingested (in contaminated food or water or from hands contaminated with feces), the oncospheres contained in the eggs are released. The oncospheres (hexacanth larvae) penetrate the intestinal villus and develop into cysticercoid larvae . Upon rupture of the villus, the cysticercoids return to the intestinal lumen, evaginate their scoleces , attach to the intestinal mucosa and develop into adults that reside in the ileal portion of the small intestine producing gravid proglottids . Eggs are passed in the stool when released from proglottids through its genital atrium or when proglottids disintegrate in the small intestine . An alternate mode of infection consists of internal autoinfection, where the eggs release their hexacanth embryo, which penetrates the villus continuing the infective cycle without passage through the external environment . The life span of adult worms is 4 to 6 weeks, but internal autoinfection allows the infection to persist for years. Eggs of Hymenolepis diminuta are passed out in the feces of the infected definitive host (rodents, man) . The mature eggs are ingested by an intermediate host (various arthropod adults or larvae) , and oncospheres are released from the eggs and penetrate the intestinal wall of the host , which develop into cysticercoid larvae. Species from the genus Tribolium are common intermediate hosts for H. diminuta. The cysticercoid larvae persist through the arthropod's morphogenesis to adulthood. H. diminuta infection is acquired by the mammalian host after ingestion of an intermediate host carrying the cysticercoid larvae . Humans can be accidentally infected through the ingestion of insects in precooked cereals, or other food items, and directly from the environment (e.g., oral exploration of the environment by children). After ingestion, the tissue of the infected arthropod is digested releasing the cysticercoid larvae in the stomach and small intestine. Eversion of the scoleces occurs shortly after the cysticercoid larvae are released. Using the four suckers on the scolex, the parasite attaches to the small intestine wall. Maturation of the parasites occurs within 20 days and the adult worms can reach an average of 30 cm in length . Eggs are released in the small intestine from gravid proglottids that disintegrate after breaking off from the adult worms. The eggs are expelled to the environment in the mammalian host's feces . Geographic Distribution: Hymenolepis nana is the most common cause of all cestode infections, and is encountered worldwide. In temperate areas its incidence is higher in children and institutionalized groups. Hymenolepis diminuta, while less frequent, has been reported from various areas of the world. Page 1 of 2 Epidemiology of Hymenolepis Nana Infections of Punjabi Villagers in West Pakistan A temporal study of Hymenolepis nana infections in man in an endemic area was conducted in the Punjab Region of West Pakistan. Infection rates were highest in the age-group 2 to 19 years and transmission appeared to be hand-to-mouth rather than through a rodent reservoir. The optimum time for transmission appeared to be during the warmer months of the year (May to October) which coincided with the greatest amount of rainfall. Although the prevalence of H. nana in our study group of 93 children and adolescents was similar at the beginning and end of the study which covered 22 months, there was an active turnover of this parasite in the study group. That H. nana can persist in man in endemic areas for long periods of time was demonstrated by the fact that 26% of the participants were infected for the entire study period. There appeared to be no correlation between systemic disturbances, such as those indicated by diarrheal stools or abnormal eosinophil counts, and H. nana infections. * . . Hymenolepis nana Control World-wide incidence 4% Treatment usually Praziquantel previously Niclosamide (both single oral dose) Health education Rodent reservoir? Screening for activity against H. nana H. nana in mice Used because - Human infection—easily maintained in mice - Armed scolex similar to other pathogenic tapeworms - Corresponds to other tapeworms in its sensitivity to standard anthelmintics Methods Mature worms collected from infected mice Terminal gravid proglottids removed, crushed under coverslip—eggs removed Eggs containing hooklets (mature) counted 0.2 ml stock soln. containing 1000 eggs/ml given to each mouse. Adult worm develops- 15-17 days. Test drug given orally – autopsied on 3rd day Std. drug given Intestine examined under dissecting microscope for worms/ scolex Response – no. of mice cleared. Symptoms It is not clear that hymenolepiasis necessarily have any symptoms. The symptoms of hymenolepiasis are traditionally described as abdominal pain, loss of appetite (anorexia), itching around the anus, irritability and diarrhea. However, in one study of 25 patients conducted in Peru, successful treatment of the infection made no significant difference to symptoms.[2] Some authorities report that heavily infected cases are more likely to be symptomatic.[3][4] Signs and tests Examination of the stool for eggs and parasites confirms the diagnosis. The eggs and proglottids of H. nana are smaller than H. diminuta. Proglottids of both are relatively wide and have three testes. Identifying the parasites to the species level is often unnecessary from a medical perspective, as the treatment is the same for both. Treatment Praziquantel as a single dose (25 mg/kg) is the current treatment of choice for hymenolepiasis and has an efficacy of 96%. Single dose albendazole (400 mg) is also very efficacious (>95%). Niclosamide has also been used. A three-day course of nitazoxanide is 75–93% efficacious. The dose is 1g daily for adults and children over 12; 400mg daily for children aged 4 to 11 years; and 200mg daily for children aged 3 years or younger.[2][5][6] Prognosis Cure rates are extremely good with modern treatments, but it is unclear that successful cure results in any symptomatic benefit to patients.[2] Complications abdominal discomfort dehydration from prolonged diarrhea Prevention Good hygiene, public health and sanitation programs, and elimination of rats help prevent the spread of hymenolepiasis. Source Hymenolepiasis. Medline Plus. References 1. ^ a b Zimmer, Carl (2001). Parasite rex: inside the bizarre world of nature's most dangerous creatures. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0011-X. 2. ^ a b c Chero JC, Saito M, Bustos JA, et al. (2007). "Hymenolepis nana infection: symptoms and response to nitazoxanide in field conditions.". Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 101 (2): 203–5. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.04.004. 3. ^ Chitchang S, Plamjinda T, Yodmani B, Radomyos P. (1985). "Relationship between severity of the symptom and the number of Hymenolepis nana after treatment.". J Med Assoc Thai 68: 423– 26. 4. ^ Schantz PM. (1996). "Tapeworm (cestodiasis).". Gastroenterol Clin North Am 25: 637–53. 5. ^ Ortiz JJ, Favennec L, Chegne NL, Gargala G. (2002). "Comparative clinical studis of nitazoxanide, albendazole and praziquantel in the treatment of ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hymenolepiasis in children from Peru". Trans R Soc Trop med Hyg 96: 193–96. PMID 12055813. 6. ^ Reomero-Cabello R, Guerro LR, Munez-Gracia MR, Geyne Cruz A. (1997). "Nitazoxanide for the treatment of intestinal protozoan and helminthic infections in México.". Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 91: 701–3.