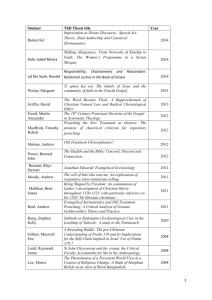

Text Criticism - Gordon College Faculty

advertisement