Bourassa_ANTH350finalpaper

advertisement

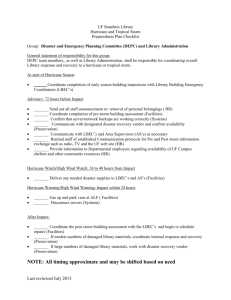

Aiding the Victims of Chaos: Are we hurting them more than helping them? Ashley Bourassa Anthropology 350 Professor Zohra Beben December 12, 2012 Abstract The intent of this research paper is to examine the results of disaster aid provided to victims following a disruptive event, examining the question of whether or not we are hurting victims more than helping them. This will be ascertained through an analysis of social scientific research presented in books, journals and newspaper articles over the past three decades. This knowledge is crucial to add to the anthropogenic catalog in order for anthropologists and society both to understand how to best help the victims of disasters during future events, as well as to provide a framework for looking at previous relief efforts. The lessons learned from these past events, as recognized through this paper, can be tailored into methods for better handling the provision of future aid in manners which are less harmful to the victims of disasters; additionally, anthropologists can learn where to target their future research from the obvious gaps in current knowledge noted in this paper. For the purpose of this paper, the terms “aid” and “relief” may be used interchangeably. Introduction Ben Wisner stated in his work At Risk that “Disasters are a complex mix of natural hazards and human action.” We see disasters as events which require an ordered response, when in fact disasters are disorderly. The current belief that disaster relief must be administered, by an outside source, in order A, B, C, D, E needs to stop. Sometimes step E should really be step A, while C and D could be left off altogether. Each disaster is different, and the cookie-cutter response currently given simply isn’t working. It is obvious that a disaster must follow with some type of aid. However, we need to determine the who, what, where, when and how of the situation before administering the same one-size-fits-all bandage over every disaster. "A focus on the long-term outcomes of relief and recovery efforts will provide some measure to ensure aid is not undermining the long-term social, economic and political recovery of affected populations." (Joakim 2008, pg. 20) Ask just about anyone in America, and they can name a disaster, and they feel that someone should help the victims. However, most people know little of what really happens once the event ends and the recovery begins, especially when it comes to the end results. The largest portion of disaster relief in the United States is provided by private insurance payments and only provided to those who pay up front on the gamble they will need the payout (Peacock et. al., 1997). Those who cannot afford such market-based coverage must rely on the generosity of others who make donations to the many non-profit organizations that exist both in America and worldwide (Rossi et. al, 1983). Research indicates that those who have suffered a disaster take advantage of as much aid as they can to help them with the recovery process (Rossi et. al, 1983). [2] How did disaster relief become what it is today? Hundreds of major disasters racked America before the founding of the Federal Emergency Management Agency came into existence, and yet the victims always found recovery by helping each other and relying on their communities to rebuild in ways which usually alleviated future hazard risks (Dyson, 2006). Over the years, organizations and mandates began to pop up that took the place of community-based relief and made it federal-centric: the American Red Cross in 1881, the Tennessee Valley Authority (flood relief) in 1934, the Disaster Relief Act of 1950, Department of Housing and Urban Development in 1974, and lastly FEMA in 1979 (Dyson, 2006). Disaster victims soon became refugees, with FEMA’s solution increasingly being to buy out homes after a disaster and let the Red Cross provide immediate aid, while natural resilience is forgotten and a heavy reliance on outside aid has come into play (Dyson, 2006). This paper argues that current disaster relief efforts often do more to further harm victims by leaving them with an increased vulnerability to additional disasters or detrimental life situations. While we as outsiders think we are helping, those in the depths of a disaster are being harmed more than if we had allowed them to depend on their communities for support and demonstrate a natural resilience, as was the protocol in the days before a federal takeover of disaster response. Current research and literature demonstrates theoretical framework on reducing vulnerability through the recovery process, however the execution of such methods simply hasn't caught up to the knowledge of what needs to be done. (Joakim 2008, pg. 22) "Although large amounts of money have been spent to rebuild after disaster events, "there is rarely any systematic consideration of whether such lengthy projects actually achieve the goals for which they were implemented" (Labadie, 2008: 576)" (Joakim 2008, pg. 22). There is a stark lack of research specifically on the results of disaster aid, and in order to complete this project, I have had to wade through dozens of books and articles that touched upon such topics, but never took the time to fully flesh out these ideas. In addition to the immediate losses suffered by disaster victims (such as loss of life or home, injury) disaster victims also face an ongoing risk for other ailments (depression, poverty, long-term illness) after the disaster ends (Rossi et. al, 1983). An increase in depression rates is often seen in households that take longer to recover due to requirements that they follow new rules on rebuilding (Rossi et. al, 1983). The displacement and loss experienced by disaster survivors is often seen by victims as a “second disaster” in their lives (Crate & Nuttall, 2009). In order to receive many types of aid provided, disaster victims must incur a substantial amount of debt which leaves them further burdened for the future (Rossi et. al, 1983). It is therefore important for aid provided to reflect these challenges and to recognize that to work properly aid must provide help and not hinder those who have already undergone so much. Anthropologists need to devote research to determining the results of relief, for the good of all victims of future disasters which are unfortunately inevitable. [3] "Many aspects of the social environment are easily recognized: people live in adverse economic situations that oblige them to inhabit regions and places that are affected by natural hazards, be they the flood plains of rivers, the slopes of volcanoes or earthquake zones. However, there are many other less obvious political and economic factors that underlie the impact of hazards. These involve the manner in which assets, income and access to other resources, such as knowledge and information, are distributed between different social groups, and various forms of discrimination that occur in the allocation of welfare and social protection (including relief and resources for recovery). It is these elements that link our analysis of disasters that are supposedly caused mainly by natural hazards to broader patterns in society. These two aspects - the natural and the social cannot be separated from each other: to do so invites a failure to understand the additional burden of natural hazards, and it is unhelpful in both understanding disasters and doing something to prevent or mitigate them." (Wisner, 2004 pg 15) I hope to add a new framework to anthropologic research on disaster relief, one which considers the darker side of doing good. I feel that it is important to consider the long-arcing results of action taken in the heat of the moment following emotion-filled events such as disasters. It is my hope that through the research I have done in writing this paper that future anthropologists will be inspired to take these ideas and further develop them into a plan for the betterment of disaster relief. Body Case Study: Centralia, PA Centralia, Pennsylvania is a now-abandoned ghost town in Columbia County, roughly one hundred miles northwest of Philadelphia (Rubinkam, 2010b). The town, built in 1841, thrived until 1962, when trash burning at a dump pit set fire to the town’s underground mines, starting a slow-burning fire that up until present time still burns, and has followed the coal veins under what the government liaison agency Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) estimates to be four hundred fifty acres (Glover, 1998b; Rubinkam, 2010b). By 1993, the state and federal governments had spent $42 million to relocate residents and buy out their properties under eminent domain (Rubinkam, 2010b). In 2010, residents filed a lawsuit with the U.S. Middle District Court, claiming the government had committed “massive fraud” in relocating them for the goal of acquiring mineral rights (Beauge, 2012; Rubinkam, 2010b). Nearby towns remain unthreatened, because where the coal outcrop ends, so too will the fire (Glover, 1998b). The town of Centralia is small, but in its prime was home to over 1,000 residents residing in about five hundred homes, and had five churches, seven saloons, a school, a bank, a post office, a hotel, and a few stores (Glover, 1998b; Rubinkam, 2010b). After the abandonment [4] procedures in Centralia began, the US Postal Service revoked the town’s zip code (Glover, 1998b). The dangers cited by the DEP have been sinkholes, poison gas, and fires spreading to above ground (Beauge, 2012). The DEP returns each quarter to monitor the area for changes, though they claim it is too dangerous to station anyone nearby permanently to keep an eye on the site (Beauge, 2012; Glover, 1998b). Signs exist all around the town’s remains warning visitors of a risk of sudden injury or death should they enter the area, but that doesn’t deter tourists or the town’s former residents from coming back to visit (Glover, 1998b). Now having burned for 50 years, the fire has never harmed, killed, or sickened a resident (Glover, 1998b; Rubinkam, 2010b). By 1998, no flames were visible on the surface, and almost all the homes had remained untouched by fire (Glover, 1998b). Air quality has remained the same as in densely-populated Lancaster, PA (Beauge, 2012). A 2008 DEP study indicated that toxic gas emissions were not a problem, and research documents presented during the 2010 court case clearly showed that the fire was “almost out” and no longer a danger to any properties, as well as indicating that the danger never was as serious as officials had made it out to be (Rubinkam, 2010b). DEP data also shows that underground temperatures have drastically gone down since measurements began at the start of the fire (Rubinkam, 2010b). In 1993, the Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania began condemning any action taking by Centralia residents to resist government buyouts (Beauge, 2012). Residents continued their appeals to stay, beginning with a petition to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in 1995, which was shot down (Glover, 1998b). The Centralia residents took their case to court yet again in 2010, with a petition stating there was no justification for the government taking their property, and presenting the above data showing that the fire danger had been over exaggerated (Rubinkam, 2010b). The citizens all claim to want no money, just a freedom to stay in the homes their ancestors built and the town they grew up in (Rubinkam, 2010b). Most residents of Centralia believe that the demolition and relocation was an attempt on the part of the government to obtain mineral rights to the 40 million tons of anthracite coal underneath the town, worth hundreds of millions of dollars (Beauge, 2012; Glover, 1998b; Rubinkam, 2010b). Once the borough of Centralia ceases to exist, the state will own the mineral rights, and have free reign to sell them to any company it chooses (Rubinkam, 2010b). Perhaps coincidentally, the law firm the state Department of Community and Economic Development hired to execute the evictions in Centralia also transferred the Centralia real estate titles to a coal company of which operations originate just outside the town (Wereschagin, 2010). In 2012, the court ruled that nothing authorizes the property owners to object to the land being taken, because the purpose for the taking no longer exists now that the mine fire ceases to be a threat (Beauge, 2012). Despite various levels of PA courts ignoring the plea of most Centralia residents, a 2006 agreement between the Department of Community and Economic Development and Centralia homeowners Robert and Mary Netchel allowed the Netchels to keep their home, which lies in the middle of the eminent domain area, other homes on each side having already been demolished (Rubinkam, 2010b). The Netchels have known ties to the law firm used both for the evictions and real estate title turnovers (DeKok, 2010). Another important aspect to note is that data was presented in [5] court indicating that the trash pit fire which started this entire incident in 1962 was intentionally set, demonstrated by evidence that gasoline was poured over the trash (DeKok, 2010). Quite the opposite story to Centralia exists in Fayette County, PA where the residents of Youngstown have been dealing with the similarly-caused Percy Mine Fire for 45 years, and they would give anything for a buyout (Glover, 1998a). In Youngstown, the government’s solution was to plug the openings to the fire with an ash-based substance that easily becomes airborne and is very harmful should it be inhaled (Glover, 1998a). The residents of Youngstown fear contaminated groundwater and soil, as well as natural gas lines running near the mine fire possibly exploding (Glover, 1998a). While the Office of Surface Mining data shows only a few homes have been affected by the Percy Mine Fire, mortgage companies deny all sales in the area, so none of the residents can sell their homes and leave, and property values are practically worthless (Glover, 1998a). Youngstown residents have petitioned to either have the fire extinguished, or to be bought out like Centralia was, but they no longer wish to be left to deal with problems they feel aren’t theirs (Glover, 1998a). When the Centralia fire first began in 1962, it could have been put out for a few thousand dollars, but was blocked by bureaucratic measures and a lack of funding, giving it time to turn into a much bigger problem (Rubinkam, 2010a). In 1983, a study was initiated by congress to determine the cost of putting out the mine fire in Centralia, as well as other mine fires nationwide. The results indicated that the cost to extinguish all underground mine fires nationwide would be $663 million (Glover, 1998b). In 1985, work began to relocate residents, and 540 homes and businesses were bought out by 1991 at a cost of $42 million (Glover, 1998b). While this fact was never compared in the court cases brought up by the residents, I feel that the main reason for Centralia being bought out was a matter of cost: the bottom line is that it was cheaper for the government to demolish the town than to fix the problem. The Abandoned Mine Reclamation Fund is a trust established in 1977, to be used for mine cleanups across the country. Instead of being used for its purpose, $3.5 billion of $4.7 billion of this money is being used to help balance the federal budget (Glover, 1998). The state of Pennsylvania has only seen $21 million from the fund, while annually the Office of Surface Mining spends $3.5 million to $4 million to fix emergency mine problems in PA (Glover, 1998). Despite the trust money being earmarked for such causes as extinguishing underground mine fires, congress must appropriate each use of it, and they generally choose not to use the money for its original purpose (Glover, 1998). In addition to fighting a lack of funding for mine-related problems, Pennsylvania also has a priority list managed by the DEP, which classifies the order in which mine fires get attention. There seems to be little indication how they decide what should come first; a 1.5 acre fire under Boyce Park made it to the top of the DEP’s priority list and was extinguished, despite being no danger to any homes or people (Glover, 1998). Whether the demolition of Centralia was a ploy to acquire mineral rights, or a decision to sacrifice a small town to save money, the unfortunate reality appears to be that the residents of Centralia have suffered needlessly in fear of a pseudo-disaster. Many elderly residents who were [6] victims of the relocation suffered severe depression before their deaths, due to being separated from their lifelong residences (Rubinkam, 2010a). Depression hasn’t been limited to senior citizens; many of the town’s younger residents experienced severe distress upon seeing their family homes they grew up in bulldozed for no reason (Rubinkam, 2010a). Several Centralia business owners lost their life’s savings when the buyout didn’t compensate them enough for their investments and they were unable to reopen in the areas they were relocated to (Wereschagin, 2010). The majority of relocated residents of Centralia wound up relocated to suburbs of Harrisburg, PA; in 2010, 81% were living on unemployment or in government-funded row houses (Krygier, 1995; Wereschagin, 2010). Had the residents of Centralia been left alone, and not provided so-called “aid” which resulted in their relocation, most if not all would still reside in their family homes in the town. Their businesses would still be functioning, and they would’ve never suffered substantial financial and emotional hardships. Case Study: Hurricane Andrew On August 24, 1992, a storm with winds as high as 200 mph known as Hurricane Andrew made landfall over Dade County, Florida. Despite living in a hurricane-prone area, most officials and residents of Dade County and surrounding areas weren’t adequately prepared for the wrath of Andrew (Hughes, 2012). 43 people died during the hurricane, and 126,000 destroyed homes left one hundred and eighty thousand people homeless; damages totaled $30 billion (Hughes, 2012). Many governmental failures aligned which prolonged the relief of the victims, but simply put, "the recovery efforts of the local, state, and federal governments following the storm prolonged the suffering of Andrew's victims" (Hughes, 2012). While in 1992, hurricane prediction models weren’t nearly as accurate as they are now, it was still apparent with advance warning that Hurricane Andrew would be making landfall over the Florida peninsula (Hughes, 2012). However, despite the warnings, no one seriously prepared, and the county, and even state, officials had been so reliant on their sense that federal aid was coming every minute that they did little to prepare before the storm (Hughes, 2012). However no one really knew what to do when they realized help was needed in the first place; then-governor of Florida, Lawton Chiles, didn’t even know how to file a request for help, nor was he aware that one had to ask before help would arrive (Hughes, 2012). Prior to Hurricane Andrew’s landfall, heavy announcements were made that shelters would be open area-wide to take in those whose homes were damaged or who had nowhere else to go (Eyerdam, 1994). Unfortunately, at the same time that knowledge was being spread to the general public about shelters, a contradictory message was going amongst the places being used as shelters: that they could only accept people with specific psychiatric conditions, or those who needed limited medical assistance for certain conditions or who needed proper administration of perishable medications/oxygen (Eyerdam, 1994). According to Eyerdam (1994), once the storm [7] started, many people were thus left with a situation of having declined evacuation thinking they would later be able to seek shelter and instead finding themselves without a place to go. Many non-English speaking tourists in town were faced with a similar problem; they had been evicted from their hotel rooms and told to get out, but evictions didn’t occur until after the airports had closed (Eyerdam, 1994). The tourists were bussed to shelters which wouldn’t take them in, so in the end many wound up weathering the storm at airports which took a lot of damage (Eyerdam, 1994). Blinded by the belief that federal help was coming and that it would be better than anything anyone else could provide, local help went first ignored, then after it arrived, unused. An article ran as far away as Seattle wondering why county residents weren’t helping each other, when FEMA and the Red Cross clearly weren’t responding fast enough (Everett, 1992). After Dade County emergency management coordinator Kathleen Hale made her famous “where are the cavalry” a plea at a press conference, donations poured in on the third day following the storm, leaving a bigger problem: how to handle the supplies provided by well-off locals. Local emergency management was overwhelmed with the donations, and had no idea how to handle storing, transporting, and distributing the much-needed goods. Food products sat around spoiling, and those in need never made use of the donations, while a significant amount of the helping hands that had arrived were needed to attempt to process the flood of goods (Hughes, 2012). Many people heard the cries for help and brought supplies to shelters, returning home feeling as though they had done their part, and never realizing that the shelters they had left a trunk full of diapers at didn’t even house a single child. The shelter staff was then left with piles of supplies no one would ever use or devote time to sending them where they were needed (Provenzo & Provenzo, 2002). Many citizens who wished to help simply didn’t know what was appropriate to donate, bringing everything from soiled or overly sexual clothes to used toothbrushes (Provenzo & Provenzo, 2002). Those who were left responsible for sorting through such things as donated clothes often broke out in severe cases of contact dermatitis, due to the horrible condition in which the clothes items donated were in (Eyerdam, 1994). Seeing people in need following the disaster, and what a slow response was happening with the federal government, many non-profit organizations made the journey down to Florida by car to bring supplies and to help residents dig out of their destroyed homes. However, many believed they would arrive in Dade County to a gathering of impoverished immigrant workers who no longer had even a cardboard hut to live in, and were severely disappointed to find middle-class white families who had lost their two-story family homes and boats; some turned back, unwilling to help those they thought were too well off to benefit (Stone, 2012). The race issue was further emphasized when a black church in Richmond Heights set up shelter and free meals and clothes, only to remain empty for two weeks as white neighbors didn’t care to intermingle no matter how needy they were (Provenzo & Provenzo, 2002). Another ethnographic hindrance was related to the language barrier. It was assumed that all residents of Dade County spoke English or had access to a translator, so all warning broadcasts before the storm and relief [8] information following the incident was broadcast in English. Many people were unable to prepare or receive help because they got lost in translation and never received a message they could understand (Peacock et. al., 1997). It wasn’t just organizations who wanted to help but didn’t find the situation as they believed; those who had volunteered their time, including firefighters and police officers from neighboring cities and states, ended up lost in the mass of displaced residents and needing aid supplies themselves (Stone, 2012). Because the destructive winds and storm surge of Hurricane Andrew were far greater than building code had allowed for in southern Florida, many hospitals saw extensive damage, and were unable to properly function in light of so many victims needing immediate treatment (Provenzo & Provenzo, 2002). Field hospitals were set up by emergency responders from South Carolina, who had experienced Hurricane Hugo and weren’t as flustered by the situation as the locals. However, the climate of Dade County was more humid and swampy than even South Carolinians had expected, and the storm surge had left even more areas underwater, making it hard to find dry land to set up medical facilities (Provenzo & Provenzo, 2002). Patients with open wounds were mixed in with those who had stomach upset, and no areas existed to quarantine patients with contagious diseases such as meningitis. Without proper toilets, areas for the gastrointestinal patients to relieve their symptoms were nonexistent. While the visiting medical help had the best intentions, proper sanitation precautions weren’t followed, and contagious diseases were spread as well as many wounds becoming infected due to improper treatment for patients who had to then return to wherever they had taken refuge in an un-air conditioned and water damaged location (Provenzo & Provenzo, 2002). Months later, reports came back of patients who had presented with bleeding wounds that needed attention, who received stitches and had their wounds bandaged up, only to later develop a nasty infection that resulted in surgical procedures and even amputation of digits (Provenzo & Provenzo, 2002). Medical care had not been better during the storm. Prior to Hurricane Andrew making landfall, both the Dade County regional public hospital Jackson Memorial Hospital and a private institution, Baptist Hospital, called in all of their pregnant mothers nearing delivery (Eyerdam, 1994). It was thought that they might deliver during the storm due to the barometric pressure drop and be unable to get to help, so they were herded into the two hospitals along with all of their families, soon “creating space, nutrition, waste disposal, sanitation and liability problems” (Eyerdam, 1994). Once power went out, the hospitals were stranded without running water (which was supplied by wells) or lights, as the backup generators placed on the rooftop in these areas to avoid water damage from the swampy location had blown away from the storm’s 180 mph winds (Eyerdam, 1994). In addition to hospitals being left unable to function, they were also being blown apart due to not meeting hurricane-proof building code, or in the case of Jackson Memorial, having a good portion under construction (Eyerdam, 1994). Several cases of babies delivered at home were reported during the storm, and Eyerdam’s 1994 account of the storm hinted that perhaps they were better off than the mothers who had sought refuge at hospitals only to deal with worse problems. [9] In some neighborhoods, homes were devastated, but not completely flattened. Those residents generally wished to stay in their homes, but local and visiting police forces herded them off to tent cities set up nearby (Provenzo & Provenzo). Those who wound up in the tent cities, or makeshift refugee camps, were worse off than if they had stayed in their damaged homes. Camps with the capacity for 1,500 people wound up with closer to three thousand cramped in them, and the camps quickly grew dirty and filled with the spread of disease (Provenzo & Provenzo). Immigration officials frequented the camps and took the opportunity to round up illegal workers and send them home, while homeowners faced different problems. Many returned back to what was left of their homes only to find they had been looted and their surviving personal possessions taken by those who sought profit out of the disaster (Provenzo & Provenzo, 2002). One month after the hurricane, eight hundred people remained in a tent city by Homestead Air Field, many who were either not allowed to leave as they were government dependents waiting on someone to sort out where to put them, or now had nowhere to go because their homes had been bulldozed while they were living in the tent cities and unable to say no to the cleanup process (Provenzo & Provenzo, 2002). When FEMA finally arrived on scene following Hurricane Andrew, victims who met FEMA’s qualification standards were provided semi-permanent housing in the form of mobile homes delivered either to their property or a trailer park (Peacock et. al., 1997). While most of those denied a home by FEMA legitimately did not meet their criteria, others were denied because they failed to meet nuclear family criteria of families with more than one head-ofhousehold living together (Peacock et. al., 1997). FEMA had expected only one application per address, and were quite confused by the state of living many people in southern Florida had grown to accept (Peacock et. al., 1997). The rebuilding process following Hurricane Andrew was so chaotic that even pop culture caught on; t-shirts began to crop up around Dade County that said “I survived Hurricane Andrew, but the rebuilding is killing me!” (Provenzo & Provenzo, 2002) Many Dade County residents experienced unexplainable feelings of sadness, depression. Local psychologists noticed an influx of patients coming in experiencing new cases of anxiety, as well as previous patients seeing their psychological symptoms worsen. Many of these patients were college students forced to go back to class before they were ready, or workers required to return to duty before they had taken care of their own personal crises (Provenzo & Provenzo, 2002). School-age children were sent back to school as soon as possible after the storm, under the philosophy that it would help them recover quicker, but the opposite was seen as they merely acted out in class or cried a lot. Many kids who rode the bus were also exhausted due to as much as 2 hour school bus rides to navigate around roads that had been destroyed or pick up students who had been relocated to camps (Provenzo & Provenzo, 2002). Several cases of suicides related to trauma from the storm cropped up, almost all of these cases were citizens who had at some point been placed in the tent cities or worked providing aid in one (Provenzo & Provenzo, 2002). [10] Dr. Robert Sheets, director of the National Hurricane Center in the 1990s, believes that most of the damage seen during Hurricane Andrew can be attributed to poor construction practices and a lack of hurricane protection measures such as shutters (Nese & Grenci, 1998). While homes built in hurricane-prone areas now have legislation-mandated features such as steel rebar reinforced walls set into concrete and standard shutters that can be closed over every window in a matter of an hour, those rebuilt immediately following Hurricane Andrew were not part of this ruling, and many fell victim yet again to the slew of storms that passed over Florida during the 2004 season (Nese & Grenci, 1998). If Dade County residents had been encouraged to move inland, or at the least rebuild better, the situation seen during Andrew would’ve never been repeated. Habitat For Humanity and other smaller home building assistance NPOs helped build homes in the area affected by Hurricane Andrew, however due to the amateur builders, these homes often did not meet new hurricane proofing codes (Provenzo & Provenzo, 2002). Following Hurricane Andrew, many people (most of whom had never lived through a hurricane before) wanted to move away from Florida (Nese & Grenci, 1998). However, even those who could afford to do so faced hindrances to their migration. Employees of the Dade County Police Department were told that they could move as far as Broward County and commute, however if they wished to leave Florida altogether, they would not receive good recommendations to find employment elsewhere (Provenzo & Provenzo, 2002). Despite the fact that 10,000 apartment homes had been destroyed, and the complex owners wished to rebuild, the owners also wanted to make some of their money back. They kicked the residents out, but wouldn’t return deposits or end contracts with the residents, forcing them to pay for as much as a year after the storm for a home they would never return to (Provenzo & Provenzo, 2002). Those on government subsidies were told if they left the county they had resided in before the storm, they would lose all their funding, yet the government left five thousand people dependent on government funding living outdoors more than three months after the storm (Provenzo & Provenzo, 2002). Many people simply couldn’t afford to leave, because home values elsewhere in the country weren’t as low as they were in Florida or they hadn’t insured their home for enough value, making it hard on anyone who had a substantial amount paid into their home to find an equivalent house outside of the area (Provenzo & Provenzo, 2002). Those who stayed were required to rebuild above flood levels – unless, that is, they paid the government a modest fee. In the end, the fee was cheaper than paying the elevation fee, which was always at least 5 digits in cost and never covered by flood or homeowner’s insurance. This meant that many homes stayed where they were despite ongoing hazards, (Provenzo & Provenzo, 2002). Overall, Hurricane Andrew was an unfortunate natural disaster that quickly turned into a social disaster as it seemed that everything anyone did was the wrong thing. 20 years later, we can merely look back and reminisce of the mistakes, learning how to change what went wrong. We now know that preparation and a system for local relief would have done wonders to help the situation. We have learned that people should not led race and other social issues taint the provision of relief. We also learned that evacuating people to worse locations is a bad idea, and [11] that amateur medical care can be very harmful. Most importantly, Hurricane Andrew should have taught us that all but forcing people to stay in a hazardous area is a bad practice, and rebuilding in a disaster zone isn’t always the best policy. Case Study: Hurricane Katrina The city of New Orleans was long vulnerable to a disaster on the grandest scale. Had the eyewall of Hurricane Andrew landed 87 miles to the east of where it did on the Gulf Coast in 1992, deaths in New Orleans would have been in the thousands or higher (Nesse & Grenci, 1998). Despite that, it was not until the last week of August 2005 when Hurricane Katrina’s 175 mph winds, storm surge and rainfall attacked New Orleans and made it the costliest natural disaster in US history. Many of us still remember what we saw on our televisions during the following weeks, but I wish to examine the results of the aid provided after the storm clouds receded. Following the Hurricane Pam exercise in 2004, many city officials believed that FEMA would actually arrive on scene prior to a major storm to help with the evacuation problem faced by New Orleans and the large population without access to transport (Heerden & Bryan, 2006). This left them unprepared for the reality of evacuation, where the people who lived where they needed to get out the most were also unable to, and in turn would need rescue following the levee breach (Heerden & Bryan, 2006). The mayor and other top officials knew the downsides to relying on FEMA and the Red Cross to arrive, and shifted the expected response to rely more on charitable donations of time and supplies to cover the needs (Heerden & Bryan, 2006). Yet the Red Cross had failed to even set up shelters in areas safe from flooding, having declined to examine 100-year flood maps that clearly indicated their shelters even outside New Orleans would be filled with water at the level of predicted storm surge from Katrina (Reckdahl, 2007). Once the National Guard mounted a response to Katrina, victims were pulled from their homes or rooftops (in some cases, whether they wanted to be or not) and deposited on the I-10 overpass in Jefferson Parish, left for days without food or water, shade or toilets (Heerden & Bryan, 2006). Those who tried to escape the human corrals such as this were stopped at gunpoint and told to wait on their rescue (Heerden & Bryan, 2006). Two days after the storm, Mayor Nagin ordered all of the police in New Orleans to halt any search & rescue activities and switch to law enforcement, stopping the “looters, drug addicts, rapists and instigators of chaos” (Heerden & Bryan, 2006). Following this, evacuees were held hostage by troops, police wasted valuable time seeking out arrests instead of rescues, a curfew was initiated that prevented medical care from reaching victims, and the media ran with the story turning it into a tale of fear (Heerden & Bryan, 2006). The airline industry took this time of cancelled flights normally filled with tourists to start Operation Air Care, providing air travel to people trapped in New Orleans (Dyson, 2006). These people were removed from the Superdome and other refuges in New [12] Orleans, to Houston and San Antonio’s similar structures, where the same situations with crowding and sanitation resumed as the people were left stranded in arenas and convention halls for as much as 9 months (Dyson, 2006). In September 2005, President Bush pledged $60 billion to initiate “one of the largest recovery efforts ever seen” in the nation (Koughan, 2007). While United States citizens believed their tax dollars had gone to help poor victims of New Orleans find a home, few residents actually saw any of that money, and those that did averaged about $2,300 only if they rebuilt in specific areas that had been most badly destroyed (Koughan, 2007). The government was essentially sanctioning those who stayed in areas that had a continued vulnerability to future storms. Mayor Nagin rejected a highly restrictive plan that would prevent any rebuilding in areas subject to similar flooding and catastrophe should another storm hit New Orleans (Koughan, 2007). Further confusion ensued as people attempting to rebuild couldn’t figure out how high off the ground their homes needed to be to meet the criteria that did pass legislature, and FEMA, which was responsible for supervising this protocol, was always giving a different answer that resulted in much rebuilding being too low (Koughan, 2007). Those who rented faced even dire straits, the cost of rent skyrocketed after so many buildings were destroyed, and rent subsidies issued by FEMA weren’t nearly enough to cover what the recipients could find to live in (Koughan, 2007). Michael Dyson noted in Come Hell or High Water that the Italians didn’t rebuild Pompeii at the foot of a volcano, so why does New Orleans keep persisting despite being as far as 20 feet below sea level in some places? Energy companies have a stronger stake in how the Gulf Coast is developed than do environmentalists, and this leads to conflicting issues of saving the barrier islands and wetlands that protect Gulf cities or drilling for oil (Dyson, 2006). Too much pressure exists to rebuild things as they were, where they were. "Other recovery research has also found that local citizens exert tremendous pressure on local government to rebuild the community to its pre-disaster form and that other forms of conflict arise from the distribution of relief and recovery aid." (Joakim 2008, pg. 5) It is poised by Joakim (2008, pg. 18) that while policymakers understand the need to rebuild in a way that reduces vulnerability, often they simply choose not to in order to rebuild more quickly, cheaply, etc. This happened in New Orleans, with a blatant disregard for the ongoing hazards resulting from putting victims of Katrina back where they were. All of the land in southern Louisiana is relatively new, built up from sediment flowing from the mouth of the Mississippi River; that was, until, the Mississippi was blocked off by dams, canals and levees (Heerden & Bryan, 2006). Now the river cannot transport sediment to where it is needed to continue building up the coastland, the system of annual river floods has been altered, and the existing areas face subsidence: buildings are sinking further down in the soft land they sit on while sea levels rise worldwide (Heerden & Bryan, 2006). The levees of New Orleans had problems from their building by the Corps of Engineers. Scientists weren’t consulted to determine if the levees would even work, construction was cut short to save money, and every big rain storm proved over the years that the levees weren’t good enough (Heerden & [13] Bryan, 2006). Despite this knowledge, “New Orleans is doing everything it can to rebuild the city exactly as it was” (Center for Public Integrity, 2007). Hurricane Katrina brought with it many lessons that should have been learned during Hurricane Andrew, such as relying on federal help to come is not the smartest move. Race issues are sadly always emphasized during disasters, and yet society still hasn’t learned not to let that happen. The dilemma of evacuation was also an issue, yet again, during Katrina as many people were moved from one bad place to another and later left homeless. Similar to what happened in Centralia, the money dedicated to relief was used for different purposes. Lastly, yet again, a city that is all but doomed was once again erected in a zone of danger, with little thought to the future vulnerability that would bring to its residents. Case Study: Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Meltdown The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactor meltdown was spurred by an earthquake and following tsunami offshore of Japan on March 11, 2011. A series of protocols failed following the natural disasters, and several of the nuclear reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant were unable to be kept cool, thus overheating and melting down. A significant amount of radioactive material was released into the atmosphere, nearby land, and ocean. In 2012, the Japanese parliament commissioned the Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Committee (NAIIC) to launch a full investigation and compile their data into a report indicating what went wrong. While the cause and blame of the nuclear accident have been much debated, what is of real concern for the purpose of my research is the response and aid provided to the victims. According to the NAIIC, the Japanese government initially wished to hide the true severity of the accident at Fukushima, which created a delay in reaction. When action finally was taken, many people in the surrounding area were slow to react because government-sanctioned nuclear accident protocols practiced and informed over the years had broadcast incorrect assumptions of safety during an accident (NAIIC, 2012). Having learned a lesson from the delay in Iodine administration following Chernobyl, the Japanese government rather quickly issued a hearty dose of potassium iodine, but with it spread a false sense of safety that no harm could come to anyone who took the medicine (NAIIC, 2012). The distribution also at some point ran out, and many were given a placebo so as to prevent panic, leaving them feeling safety from a precaution they didn’t even receive (NAIIC, 2012). Despite the issuance of potassium iodine treatment, radiation exposure still occurred. Forty-five percent of children in areas surrounding Fukushima Daiichi prior to the explosion now test positive for thyroid radiation exposure, which is linked to cancer later in life (Onishi & Fackler, 2011). [14] Following the radiation leak, the government issued evacuation orders for much of the area surrounding the plant (NAIIC, 2012). Unfortunately, the government provided few details to the agrarian families about why they were evacuating, nor did they give direct instruction as to where they should go, lead to a lot of confusion and many people evacuating to more contaminated areas (NAIIC, 2012). The government also withheld information on how much radiation was released, in a few instances allegedly reducing the readings as much as 3 decimal points before broadcasting contamination levels to citizens (Jamail, 2011). A large group of residents, including children, were evacuated to the north because the Japanese government had given false information that the radioactive contamination spread into the atmosphere would be blowing south with the wind (Onishi & Fackler, 2011). These reports were wrong, because the radiation plume spread to the northwest, in fact directly over the town Tsushima, which was a gathering area for evacuees only 20km outside the Fukushima Daiichi plant site (Onishi & Fackler, 2011). In some areas, shelter-in-place orders were given, and residents were left in locations with higher than acceptable radiation levels until April, seemingly forgotten about (NAIIC, 2012). Other groups of people were forced to move multiple times, resulting in the deaths of 60 elderly and sickly patients (NAIIC, 2012). Many evacuation orders were lifted far sooner than they should have been, stopping monitoring of radiation levels and allowing people to return to unsafe areas with little regard for if it was safe yet, and telling them protective clothing is no longer needed (Gordon, 2011). By April of 2011, evacuees were given prefabricated structures to live in as temporary housing, but the government later decided these were unsightly and the areas were too cramped, and chose to demolish the homes and send the residents back to wherever they had come from (Onishi & Fackler, 2011). To help ease the minds of people forced to move back to radiation contaminated areas, the government raised the legal exposure limit to radiation (including for children) from one to twenty millisieverts per year, allowing them to live in areas that were simply unsafe (Onishi & Fackler, 2011). Meanwhile, the Japanese Prime Minister was telling people that they would never be able to return to their homes near Fukushima, which would be demolished, as they will stay contaminated for many decades (McCurry, 2011). These conflicting actions have created a large homeless community with little place to go in a cramped island nation with limited land – over 150,000 people were evacuated at some point or another following the nuclear disaster (NAIIC, 2012). Most of the residents of the areas surrounding the Fukushima Daiichi plant were part of an agrarian lifestyle prior to the disaster, many making a living off growing grain and produce, farming cattle, or fishing. Now that the surrounding water, forest and topsoil are contaminated for decades, these people have little other skill sets to provide for themselves, and are unemployed (NAIIC, 2012). The government of Japan is not happy with this, and encourages the evacuees of Fukushima to return to old activities, telling them that the land and water are safe (NAIIC, 2012). They are left with little to do besides go against their moral conscience and [15] provide radiation-contaminated food to the rest of their country, or to disobey the government’s orders and remain homeless and jobless (NAIIC, 2012). Japanese culture itself has hindered the people’s resilience to the Fukushima Daiichi disaster: it is against their nature and bringing up to question authority, be it the authority of a parent or a government official (NAIIC, 2012). Only one lawsuit has been seen as a result of the disaster, and it was unsuccessful in Japanese court (Onishi & Fackler, 2011). While it is well known amongst the younger generation of Japan that eating the local food carries with it a high risk of low-level radiation exposure, the elderly generations trust the government’s reassurances that the food is safe and force meals made from local produce and fish upon their children, who must oblige to please their elders (NAIIC, 2012). The Japanese government, and the world as a whole, should look at the actions during the nuclear disaster and realize that things like this should not happen in the modern age. A government should never consider it acceptable to lie to its citizens or withhold crucial information, for any reason. If evacuations are mandated, they should follow certain orders that are specific and centered around avoiding the disaster zones instead of relocating people into greater hazards. Any preventative therapy (such as the iodine) provided should only be instituted with the honesty that it is not fully protective, and an evacuation or change in behavior should still follow. Most important, if a government is faced with a situation where a former living area is rendered unsafe, they should not say this while at the same time leaving the victims nowhere else to go. Conclusions As we have seen through the case studies, more often than not aid becomes more of a hindrance than a help to disaster victims. That is not to say immediate aid, such as rescue and medical care, should not be provided. However, reforms must be made to how we look at providing aid during disaster scenarios and a system of checks-and-balance would be useful. Joakim (2008, pg. 16) believes that vulnerability reduction should be the backbone of disaster recovery efforts. Actions must be calculated, especially during the permanent rebuilding process, to ensure that they won’t instead increase vulnerability. "Through the actions taken during the post-disaster recovery period, every action taken on account of one disaster must be designed and managed also to reduce vulnerability of the future. In this way, vulnerability reduction itself would be socially and environmentally sustainable development." (Joakim 2008, pg. 11) Aid has come a long way over the spectrum of time covered by the case studies, yet in most ways, has not improved in regards to critical flaws that are the most harmful to already suffering disaster victims. Many of the same mistakes made during Hurricane Andrew were [16] repeated following Hurricane Katrina, along with new flaws becoming apparent. Things learned from Chernobyl were applied during Fukushima, but things still went wrong. Are we really learning all that we should from our past disasters, and applying them to future events? In the following, I will list my suggestions for the future of disaster relief actions. Sociology and Relief All of the case studies examined exhibited some form of prejudicial relief distribution based on race, age, class, gender or location. This cannot continue to happen. All humans must be created equal in the wake of a disaster, regardless of their skin color, genitalia, or where they set up their home before the event. Society worldwide should be educated enough on sociology at this point to understand that a time of need is the last time that prejudice should be coming into play. Preparation before Response In the case studies of both hurricanes, it was clearly seen that better preparation prior to landfall would have made a world of difference when it came to the amount of relief required after the storms subsided. Local preparation needs to become key – relying on a federal response too often leaves your head below the water. Each city in America (if not the world) with inherent hazards needs to have a plan to reduce vulnerability, prepare quickly enough when a warning happens, and respond sufficiently on its own without waiting on federal help if a warning doesn’t come first. A system should also be in place to properly collect and distribute local aid donations, so that further mayhem isn’t created by an influx of charity. Additionally, a plan should be firmly rooted that establishes how many incoming aid works can be accommodated, and where, so that they aren’t merely added to the number of bodies that need care following a disaster. It would be better to turn away those who wish to help because there is no room for them, than to have them come and not be useful, only added to the list of victims. "Preparedness of the un-thought might be viewed broadly as any composite of three formations: the camouflaging of things, or the keeping of things on hand but held out of view; the repurposing of objects, or the keeping of things in view but not at hand; and the vague indeterminacy of everyday practices, or the keeping of preparedness on hand but held out of mind. In short, to bring the un-thought into the thought is a call to be alert to the ways in which concealments are laid on the everyday of things, concepts, and concealment itself. If the work of preparedness is, by definition, work done in advance of the disaster, then the work of preparedness of the un-thought moves preparedness back still further, prior to the distinction that rends disaster and the everyday from one another." (Sayre, 2011) Intentional vs. Unintentional Mistakes The intentions of any organization, government or private, providing so-called relief need to be examined before they are allowed to take drastic measures. If the state organizations responsible [17] for removing Centralians from their homes had been supervised by a watchdog group of some type, hundreds of families would not now be living in poverty and battling depression. If someone had been monitoring the Japanese government, information would not have been withheld to save face while sacrificing the future health of hundreds of thousands of citizens. While inciting panic is always a risk, it is better to be open and honest with the victims about the dangers they face so that they can respond with their eyes wide open instead of being blindsided by later knowledge and left to wonder what they would have done if only they had known. When & Where to Rebuild Sometimes a disaster is a random event that wasn’t even tied into a known vulnerability (9/11 for example). However, in most of the case studies I have presented, there were known hazards in the communities that became victims. Once one event has indicated that an area has severe vulnerability, it should be seen as an opportunity to relocate the entire community. Relocation is hard on disaster victims, and the feeling of uprooting from their community being dissolved is long lasting (Crate & Nuttall, 2009). However, after living through a disaster many people feel as though they have already lost their community, and this could be seen as a perfect time to relocate without putting additional stress on the community. Following displacement, people need to reestablish their lives as quickly as possible to regain a sense of structure in their lives (Crate & Nuttall, 2009). Instead of allowing them to return to the demolished communities and reestablish only to later become uprooted again, they should initially be allowed to reestablish in a safer locale. Following Hurricane Andrew it was thought that the southern Florida area affected could be “built back better.” However, according to Joaquim, "it is found that although many governmental and aid organizations have adopted the term 'building back better' to define the reconstruction and recovery activities, defining what building back better encompasses has been difficult and poorly researched." If building back better becomes building back worse, or building back just for the sake of it, nothing has been accomplished. Leaving an area barren is better than building a community that grows only to be taken out a second time by the same type of disaster. It has oft been said, if you build it they will come. When a city is there waiting, people will fill it up. Don’t lead them blindly into hazards. The days of paying victims to stay where they are, continually resurrecting cities that nature wants to suck back into the earth, and trying everything possible to prevent relocation should have ended at the dawn of the industrial era. Don’t Overlook Natural Resilience Humans have been dealing with climate change for centuries, and have always managed to fall back on adaptability as a coping mechanism (Crate & Nuttall, 2009). Resilience is the mirror image of vulnerability, and explains how civilizations have survived chaotic events and not collapsed. (Crate & Nuttall, 2009). When the victims of a disaster have their resilience [18] undermined, it creates a sense of helplessness that prevents their ability to recover mentally from what they have gone through (Crate & Nuttall, 2009). Joakim suggests that policymakers often overlook a community's built in resilience, feeling that they are incapable of rebuilding without some outside help. This leads to an increased likelihood of ignoring hazards (2008, pg. 20). "In terms of vulnerability reduction, an understanding of the local context is required to ensure that recovery efforts are addressing the root causes of vulnerability within the community as well as engaging in effective strategies for recovery that have long-term sustainability." (Joakim 2008, pg. 21) Officials at the federal and local levels should provide what is necessary for the immediate, but particularly when it comes to long-term rebuilding, allow the community to feel out what it needs on its own without imposing impractical overly-restrictive mandates. Proper Use of Allocated Funds Money reserved for disaster aid should be used for what it was intended for. Padding the federal budget with the grant money intended to restore abandoned mines in Pennsylvania is wrong, as is money from Katrina never making it to the hands of victims. Many disaster victims lose their entire existences during a disaster, and reestablishing is costly. They need all of the help that they can get, especially those who cannot afford to buy into the market-based relief system. The government should always look into cutting other areas before taking money away from disaster relief, which is cutting one’s nose off to spite their face. Stop Untrained Medical Care During Hurricane Andrew, many people became sick from receiving medical care from untrained practitioners. This care was mostly provided in non-urgent situations. Had everyone just waited until the storm subsided, it would have prevented many infections and amputations that later occurred because of the procedures performed in unsanitary conditions. Protocol should be in place indicating that non-lifesaving medical care should not be performed by untrained persons in unsanitary conditions. A cut can wait to be stitched up, allowed to scab over on its own, rather than immediately being sealed by someone without any medical training that knows nothing about how to prevent the spread of infection in an already more unsanitary than usual environment. Calling Anthropologists: More Research, Please It is crucial for anthropologists and sociologists to devote more time to studying the implications of disaster relief. Society relies on social scientists to educate on necessary structural changes. Right now, there is little solid research on the after-effects of disaster aid. Bits and pieces remain scattered here and there in existing literature, but no one has devoted a full work to the topic. It would be helpful to alleviate future disaster response failures if research providing a clear framework existed. [19] Overall, it is important to remember that we cannot simply stop providing disaster relief. We need to change how we look at the provision, and after making some fundamental reforms to the execution of relief provision in wake of a disaster, resume with a new outlook. In our increasingly chaotic world, disasters will remain inevitable. All that we can do is continue learning how to best prepare for and respond to events we can do little to prevent with the attitude that every lesson learned is another life saved. Bibliography Beauge, John. 2012. Court Denies Centralia Property Owners Looking to Keep Their Homes. Patriot-News, February 23. DeKok, David. 2010. Fire Underground: The Ongoing Tragedy of the Centralia Mine Fire. Globe Pequot. Dyson, Michael Eric. 2006. Come Hell or High Water. New York, NY: Basic Civitas. Everett, S. 1992. County Residents Can Aid Hurricane Andrew Victims. Seattle Times, August 31. Eyerdam, Rick. 1994. When Natural Disaster Stikes: Lessons from Hurricane Andrew. Hospice Foundation of America. Glover, Lynne. 1998a. Burning Beneath the Surface. Tribune-Review, May 03. Glover, Lynne. 1998b. Mine Fire Still Rages Beneath Tiny Town. Tribune-Review, May 03. Gordon, Jeremy. 2011. Another Evacuation Order Lifted. World Nuclear News, August 15. Heerden, Ivor Van and Mike Bryan. 2006. The Storm: What Went Wrong and Why During Hurricane Katrina - The Inside Story From One Louisiana scientist. New York, NY: Viking. Hughes, Tracy. 2012. The Evolution of Federal Emergency Management Since Hurricane Andrew. Charles Town, WV: American Public University. Jamail, Dahr. 2011. Citizen Group Tracks Down Japan's Radiation. Al-Jazeera, August 10. Joakim, Erin. 2008. Post-Disaster Recover and Vulnerability. Ontario, Canada: University of Waterloo. Kroll-Smith, J. Stephen. 1990. The Real Disaster is Above Ground: A Mine Fire & Social Conflict. Lexington, KY: University Press of Lexington. [20] Krygier, John. 1995. Taste Place & the Taste of Place: Centralia, Pennsylvania. Globehead! The Journal of Extreme Geology. 1. no. 2. Labadie, John R. 2008. Auditing of Post-Disaster Recovery and Reconstruction Activities. Disaster Prevention and Management. Vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 575-586. McCurry, Justin. 2011. Fukushima Disaster: Residents May Never Return to Radiation-Hit Homes." The Guardian, August 22. Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission. 2012. The National Diet of Japan. Nese, Jon and Lee Grenci. 1998. A World of Weather: Fundamentals of Meteorology. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt. Onishi, Norimitsu and Martin Fackler. 2011. Anger in Japan Over Withheld Radiation Forecasts." New York Times, August 8. Peacock, Walter Gillis, Betty Hearn Morrow and Hugh Gladwin. 1997. Hurricane Andrew: Ethnicity, Gender and the Sociology of Disasters. London, UK: Routledge. Provenzo, Eugene F. Jr. and Asterie Baker Provenzo. 2002. In the Eye of Hurricane Andrew. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. Rather, Dan, Jenni Bergal, Sara S. Hiles, Frank Koughan, John McQuaid, Jim Morris, Katy Reckdahl and Curtis Wilkie. 2007. City Adrift: New Orleans before and after Katrina. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. Rossi, Peter H., James D. Wright, Eleanor Weber-Burdin and Joseph Pereira. 1983. Victims of the environment: Loss from natural hazards in the United States, 1970-1980. New York, NY: Plenum Press. Rubinkam, Michael. 2010a. "Few Remain as 1962 Pa. Coal Fire Still Burns. Associated Press, February 05. Rubinkam, Michael. 2010b. "PA Coal Town Above Mine Fire Claims Massive Fraud. Associated Press, March 09. Sayre, Ryan. 2011. The Un-Thought of Preparedness: Concealment of Disaster Prepardness In Tokyo's Everyday." Anthropology and Humanism. 36. no. 2: 215-24. Stone, Rick. 2012. The Best Intentions.... Miami News Herald, July 19. Wereschagin, Mike. 2010. Centralia's Last 9 Fight Eviction. TribLive, May 02. Wisner, Ben; Piers Blaikie; Terry Cannon and Ian Davis. 2004. At Risk: Natural Hazards, People's Vulnerability and Disasters. 2nd Ed. London, UK: Routledge. [21]