Issues in Psychology

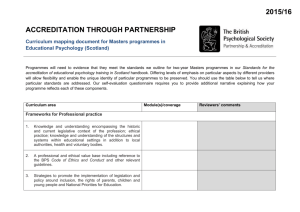

advertisement