Yana Sistovari essay on Pythian Oratorio

advertisement

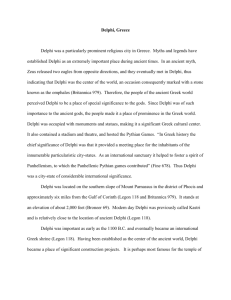

Yana Sistovari, 2013 1 Wisdom (Sophia), Prophecy and Divine Inspiration__Scholia to Staniewski's Journey from Delphi to Lazienki and Gardzienice. Staniewski in Sibylline fashion converts the long-distant past into a prophecy for a new theatrical future. His new project--a series of oratorios based on prophetic texts and oracular sayings-- marks yet another departure in his ventures into the hidden territories of antiquity. The 'oracular' oratorios follow Metamorphoses, which revitalized ancient Greek music and the Electra, in which ancient cheironomiae (hand gestures) became the fabric of another new form of theatre by Staniewski-- the 'theatrical essay.' Inexhaustible in his search for the life force of theatre, Staniewski peeled back layers of civilization and was led to the centre of the Greek world--to Delphi. High above the Pleistos Valley, between the twin peaks of Parnassos, the site possesses a tremendous power, a dynamis, which drew generation after generation of those eager to consult the oracle--to hear the voice of Apollo, the most prophetic of gods, through his priestess, the Pythia. The temple of Apollo is overlooked by the towering Phaedriades cliffs and deep beneath the earth lie seismic forces which have given the landscape its shape and seem to bring the cavernous spaces below the earth in touch with the heavens. There, in the summer of 2008, Staniewski led a procession of actors, film crew, and locals from Delphi, along the steep path, past the Phaedriades to the enormous, many-chambered Korykian cave in which he filmed the sacrifice of Iphigenia for his film Iphigenia at A... The Korykian cave, long before Apollo's advent to Delphi, was dedicated to Pan and the Nymphs, who are strongly associated with trance and possession. Caves are often the seats of prophecy for entranced prophetesses such as the Pythia and the Sibyl of Cumae. Staniewski's pursuit of the 'divining' spark therefore leads him almost inevitably back to Delphi--this time to the temple sanctuary of Apollo. Yana Sistovari, 2013 2 Carved on the temple1 and dedicated to Apollo were 147 pithy sayings including the famous 'know thyself' [γνωθι σ'αυτον transliterated as gnothi s'auton] and 'nothing in excess' [μηδεν αγαν--mithen aghan] attibuted to Seven Sages [sophoi] living in the early decades of the sixth-century BCE. The first explicit attestation is in Plato who enumerates the Seven Sages as Solon from Athens, Chilon from Sparta, Periander from Corinth and four others from Eastern cities2. These men were not only philosophers and poets but also involved in contemporary statecraft. They were, according to Plato, men of "perfect education".3 Their wisdom (sophia) was forged in an agonistic spirit and delivered in the form of short maxims designed as much to provoke thought as to charm and captivate the listener. The sayings were "short and compressed--deadly shot[s]", "twisted together, like a bowstring, where a slight effort gives great force." Socrates calls them "far-famed inscriptions, which are in all men's mouths --'Know thyself,' and 'Nothing too much.'4 The Seven Sages "assembled together and dedicated these as the first-fruits of their lore to Apollo in his Delphic temple, inscribing there those maxims which are on every tongue..." 5 While 'sophia' (wisdom) incorporates many kinds of knowledge and expertise (as is manifested in the Platonic corpus), it also preserves a connection with the poet and the seer, and relates to "knowledge about the gods, man and society, to which the sophos (the wise person) claims privileged access"6 . The 1 Inscribed on the temple at Delphi which was built toward the close of the sixth, or early in the fifth, century B.C.E. The question of its exact position on the temple, as well as of its authorship, lies in dispute. Moreover, we cannot be certain whether it was placed on the temple because of its prominence in earlier Greek thought, or whether it became prominent in Greek thought largely because of its presence on the temple; but that it was already a current "proverb" when it was placed on the temple, and that its presence there served to give it a heightened importance, is a natural surmise. 2 Pittacus of Mytilene, Bias of Priene, Cleoboulos of Lindos on Rhodes, Thales of Miletus 3 Protagoras 343a to 343b NOTHING IN EXCESS is quoted five times in the works of Plato-three times in connection with KNOW THYSELF and twice by itself. 4 Protagoras 342e 5 343b 6 Kerferd, The Sophist Movement, 1981:24; Gernet, L., the Anthropology of Ancient Greece, 1981. Yana Sistovari, 2013 3 sophos can advise and instruct on moral conduct employing technical skill as well as exerting an aesthetic/emotional impact: "his/her 'uncanny verbal, musical and histrionic powers can excite the ear and the eye as well as the mind, dazzle and delight an audience, and arouse in it irresistible feelings of....sympathetic engagement and emotional release--'tears and laughter,' pity and fear'"7 The 147 sayings of the Seven Sages (sophoi) were used as a school book for the Greek world from the sixth-century BCE8 till well after the fall of Byzantium (1453 AD). There are also countless unedited manuscripts on the 'sayings' in libraries and institutions and three different text-traditions.9 What is less known and what lends particular momentum to Staniewski's oratorio is that the sayings were in all likelihood performed in competitive display during the Panhellenic games where the sophoi would assemble and enchant listeners with their verbal performances. The Seven Sages probably set the precedent for displays of philosophical magnetism by sophists such as Protagoras who, according to Plato "charmed [his followers] with his voice like Orpheus. And they, being charmed, follow in pursuit of his voice".10 A connection between the voice and mantic power of the Delphic oracle is elaborated by Heraclitus, the sixth- century philosopher, in the earliest mention of the Sibyl: "The Sibyl, with frenzied mouth...uttering words without laughter without adornment and without incense reaches over a thousand years with her voice through the god."11 7 Griffith, M. "Contest and Contradiction in Early Greek Poetry" in M. Griffith and D.J. Mastronade, eds, Cabinet of the Muses: Essays on Classical and Comparative Literature in Honor of Thomas G. Rosenmeyer, 1990:188-89 88 established as a basis for Athenian educations in the times of the Pisistratids (before 514BCE) according to Plato's Hipparchus 228c-229. 9 Sosiades, Klearchos, Anonymous 10 Plato, Protagoras 315a. 11 DK 22B 92. This highly controversial quotation by Plutarch is offered as a counter-example to charm and spell-binding but serves as an example of the power and reliability of the oracle. It also directly contradicts the Yana Sistovari, 2013 4 This interconnectedness between philosophical magnetism, wisdom and the voice 12 leads us to Delphi where the Sages inscribed their sayings as a firstfruit offerings to Apollo. The sanctuary thus become a repository of wisdom while at the same time the wisdom is legitimized through Apollo's power. Both inscriptions and song are thus essential means for communicating and disseminating wisdom to an expanding Greek world that looked to Delphi for religious guidance. This finds its full expression in Staniewski's Delphic inspiration to have the Sages' 147 sayings carved on a marble replica of the omphalos in Delphi by the Greek sculptor Christina Papageorgiou, and to have it transported to Lazienki and installed in front of the Temple of Sibylla. The omphalos or 'navel' (it is said) marks the point at which two eagles sent by Zeus had met in order to determine the centre of the world. The omphalos in Delphi rests in what was once most probably the temple adyton from where the Pythia uttered her prophecies. Now, it will rest by the Temple of Sibylla in the Royal Lazienki. Maybe Staniewski's inspired idea to bring the symbol of the centre of the world to Warsaw is prophetic in more ways than one and a sign of the strength of theatrical intuition. London May 2013 established view that Sibyl, unlike the Pythia who is a medium for the god Apollo, speaks her own mind. Sibyls are clairvoyants and Pithyas are mediums (Parke). 12 The connection between the voice and Delphi stretches back to a time predating the building of the stone temple of Apollo which, in a poem, Paean 8, by Pindar ( c. 522-443 BCE) replaced a bronze temple where "six golden Charmers (Keledones) sang above the gable. But the sons of Cronus opened the ground with a thunderbolt...astonished at the sweet voice, that foreigners ....wasted away hanging up their spirit as a dedication to the sweet voice." The enchanting power of the voice as that of the Muses for inspiration and the Sirens for luring away thus remains below the earth at Delphi. This mythological account is reported by Pausanias 10.5 9-22.