Academic Interventions

advertisement

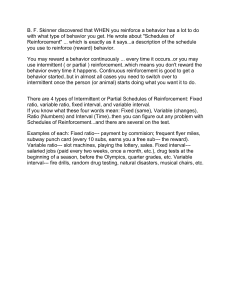

Academic Interventions- Direct Instruction Page |1 Academic Interventions Direct Instruction As increasing numbers of children with disabilities are being educated in general education settings, the question repeatedly arises as to how direct instruction can be integrated into typical classroom routines and activities. This is a particular concern for some children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) whose early learning experiences have been primarily limited to structured 1:1 teaching guided by ongoing assessment and data collection. When the time comes for a student with ASD to transition to a less restrictive environment, whether a general or integrated special education setting, often the primary challenge becomes how to provide ample opportunities for individualized instruction and data collection within the daily activities and routines of the classroom. Direct instruction may be a viable option. However, before deciding how direct instruction might be implemented, it is advisable first to clarify individual perceptions of the meaning of the term. The term direct instruction has a number of possible associations. It may refer to a set of effective teaching practices identified by Rosenshine (1976) or to Hunter’s (1980) model of direct teaching described as Instructional Theory into Practice (ITIP). The Direct Instruction (DI) model described by Becker, Engelmann, Carnine, and Rhine (1981) specifically refers to a highly publicized longitudinal study called Project Follow Through (Schweinhart, 1997; Stebbins, St. Pierre, Proper, Anderson, & Cerva, 1977.) and the more than 50 published DI programs for teaching core academic subjects, primarily at the elementary level. More recently, the term direct instruction has become synonymous with structured teaching methods of any type (Gersten, Woodward, & Darch, 1986). As the specific models associated with direct instruction Academic Interventions- Direct Instruction Page |2 are amply described elsewhere, no attempt will be made to summarize them here. If you are interested in information on methods related to one of the above paradigms, please consult the reference list at the end of this lesson. For the purpose of this topic, we will define direct instruction as a continuum of effective strategies for increasing opportunities for learning in the least restrictive setting. At the heart of any discussion of direct instruction is the role of the adult in the child’s learning experience. In comparison with more child-centered teaching methods, direct instruction commonly is characterized as teacher-directed (Stein, Carnine, & Dixon, 1998). Consequently, the responsibility for student learning (or lack thereof) rests squarely with the teacher’s design and delivery of instruction. This may present a philosophical challenge for the general education teachers, trained to work with typically developing groups of students, who see their role as a facilitator of learning (Bredekamp, 1987). On the other hand, special educators, generally trained to view themselves as interventionists, may have more knowledge of direct instruction, yet lack an understanding of how to integrate opportunities for individualized instruction into the framework of the general education classroom. In this topic we will identify and describe effective strategies for increasing opportunities for direct instruction in the least restrictive classroom setting. Specifically, we will present researchbased instructional strategies that can be integrated into general education settings to maximize opportunities for individualized instruction of children with disabilities, including ASD. Direct instruction strategies outlined in the following lectures are part of a hierarchy of effective practices on a continuum representing least-to-most adult direction (Figure 1). Academic Interventions- Direct Instruction Page |3 Environmental arrangements and supports make up the top half of the continuum of effective instructions, representing the least intrusive instructional strategies for the classroom. That is, these methods allow the greatest opportunity for student-initiated learning and are less dependent on adult instruction. Along with the use of peers as intervention agents, these practices provide the structure that supports teaching and learning in a classroom setting. However, for many children, including students with ASD, more directive methods of instruction will be required. These strategies are represented by the base of the hierarchy and form the content of the lecture on direct instruction: reinforcement strategies, naturalistic procedures, and response-prompt strategies. How do you select the most appropriate instructional strategy for a student? Research suggests that increased generalization of learned skills is associated more with opportunity for child-initiated behavior and less with adult-directed learning. It follows that the Academic Interventions- Direct Instruction Page |4 most adult-directed instructional strategies would be reserved for the most significantly delayed student behavior, or for critical behaviors or skills that require rapid acquisition or extinction. With these thoughts in mind, Bailey and Wolery (1992) proposed additional considerations for selecting appropriate instructional strategies: 1. Is the strategy appropriate for the child’s target level of performance: acquisition, fluency, maintenance, or generalization? 2. Does the strategy promote independence or increased participation? 3. Can the strategy be integrated into the child’s daily activities and routines and across developmental domains? 4. Does the strategy promote active engagement by taking into consideration child preferences and optimum response modes? 5. Is the strategy efficient, i.e., when compared to other strategies; it produces the most effective results in the most natural setting in the least mount of time. In other words, the most effective instructional strategy for a student is the one that offers the greatest chance for success, in the shortest amount of time, in the most natural (least restrictive) setting, with the least adult assistance. When more than one strategy seems to meet the above criteria, Bailey and Wolery (1992) recommend that the “less intrusive intervention and arrangements should be used” (p. 176). It is for this reason that the least intrusive direct instruction strategies are presented first as the reader proceeds through the following lectures. Academic Interventions- Direct Instruction Page |5 Reinforcement Strategies Definition: Reinforcers can be thought of as any event following a behavior that increases the probability that the behavior will occur again. For many students, especially those with ASD, reinforcement is critical to the learning process. Consequently, if additional opportunities for direct instruction are to be created for these students in the least restrictive settings, teachers need to identify the least intrusive methods of reinforcing desired behaviors and skills. In the past, guidelines for Developmentally Appropriate Practice (DAP) emphasizing the young child’s natural motivation to learn from meaningful activities were narrowly interpreted as an indictment of the use of external reinforcement. However, more recent publications (Bredekamp & Rosegrant, 1993; Kostelnick, Stein, Whiren, & Soderman, 1993) suggest that individual differences in children call for different levels of adult support, including positive verbal communication (i.e., encouragement and praise), consistent consequences to teach appropriate behavior, and direct instruction in the form of simple, positive statements (Kostelnick et al., 1993). The positive reinforcement strategies included here are supported by a significant body of research attesting to their power in changing behavior in children (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 1987). The four reinforcement strategies to be discussed here include: Differential reinforcement Correspondence training Behavioral momentum Response shaping Academic Interventions- Direct Instruction Page |6 Reinforcement Strategy #1: Differential Reinforcement Definition: “Reinforcement is provided for skills when they occur at the appropriate times and places, and it is not provided when they do not” (Wolery & Fleming, in Bailey & Wolery, 1992, p. 387). At least four types of differential reinforcement have been used successfully with young children: differential reinforcement of other behaviors (DRO), differential reinforcement of incompatible behaviors (DRI), differential reinforcement of alternative behaviors (DRA), and differential reinforcement of low rate behaviors (DRL) (For more in-depth information on differential reinforcement, please refer to lesson "Differential Reinforcement" in Behavioral Interventions unit or click here). Example #1: Differential Reinforcement of Other Behaviors (DRO) - Reinforcement is delivered at fixed intervals when a problem behavior has not occurred. For example, using a timer, the teacher provides a signal (e.g., eye contact, “thumbs up”) to a target student during circle time whenever the student goes 5 minutes without putting her thumb into her mouth. (Note: The initial interval for receiving reinforcement should be slightly less than the average length of time between episodes of the target behavior.) Example #2: Differential Reinforcement of Incompatible or Alternative Behaviors (DRI /DRA) These two strategies are similar: they involve reinforcing appropriate behavior rather than the absence of problem behavior. By reinforcing behaviors that are either incompatible with or an alternative to the problem behavior, it is anticipated that appropriate behaviors will eventually replace the problem behavior. For example, sitting with hands in lap is incompatible with thumb sucking; that is, the two behaviors cannot occur at the same time. DRI for keeping hands in lap Academic Interventions- Direct Instruction Page |7 during circle time could result in a decrease in thumb sucking and an increase in hands in lap. DRA for the same problem behavior could involve reinforcement of an alternative behavior such as increased participation (singing or verbal responding). Example # 3: Differential Reinforcement of Low Rate Behaviors (DRL) - Reinforcement is provided for reduced occurrences of a problem behavior. It is particularly useful for behaviors that are appropriate at some level but problematic when they occur with too great a frequency. Data are collected on the frequency of the behavior and a more acceptable frequency for occurrence of the behavior is then identified. Incremental decreases in the behavior are systematically reinforced. For example, this strategy might be helpful for the thumb-sucking behavior mentioned above, if the goal is not to extinguish thumb sucking but to see it decrease at times when it interferes with participation. Using the DRL strategy, the student would receive verbal encouragement as thumb sucking decreases across the day. She would be reinforced for limiting her thumb sucking to the reading corner. Reinforcement Strategy #2: Correspondence Training Definition: Children are reinforced for making accurate statements about their intended behavior. The assumption underlying this strategy is that positive verbal behavior can influence nonverbal behavior in a positive way. Example: At preschool, a child who tends to wander from one area to another during center time is asked to choose which center he will visit first and to explain what he is going to do there. A few minutes later, the teacher reinforces the child if he did what he said he was going to do. Academic Interventions- Direct Instruction Page |8 Reinforcement Strategy #3: Behavioral Momentum Definition: Children are reinforced for demonstrating a series of behaviors on command, beginning with behaviors they are more likely to display with ease and ending with a request to perform a behavior they are less likely to display. Example: For a child who resists toileting, the adult would use the following series: “Romeo, give me 5!” “Good! Clap hands!” “Yea! Shake!” “Good shaking! Time to go potty now. Come on!” Reinforcement Strategy #4: Response Shaping Definition: Response shaping involves reinforcing small approximations of a desired behavior and gradually reducing reinforcement until the child’s behavior more closely approximates the target behavior. Example: Throwing a ball with accuracy is difficult for a child with increased or decreased muscle tone. Using response shaping, the adult first reinforces the child simply for throwing the ball in a forward motion. After the child becomes consistent at throwing in a forward direction, Academic Interventions- Direct Instruction Page |9 the adult reduces reinforcement and makes it contingent on the more desired behavior, saying, “Good try, now throw it to me.” Naturalistic Strategies Naturalistic teaching strategies, also referred to as “milieu” teaching, involve planned episodes of brief adult-child interaction that take advantage of naturally occurring reinforcers in the course of ongoing activities and routines (Halle, Alpert, & Anderson, 1984). Naturalistic strategies were originally designed to promote generalization of communication skills from therapy settings to natural environments. However, these strategies have also proven effective across developmental domains for teaching new skills as well as improving existing ones. Five variations of naturalistic instruction include: Modeling Expansions Naturalistic time delay “Mand” modeling Incidental teaching Naturalistic Strategy #1: Modeling Definition: The concept of modeling (Bandura, 1965) as an instructional strategy is derived from research suggesting that typical children tend to imitate the behavior of children and adults who are significant to them, especially when therefore, such behavior is reinforced. One of the primary rationales for the inclusion movement, is that children with special needs will learn from the behavior of nondisabled peers (Peck & Cooke, 1983). For such learning to occur, children with disabilities must be aware of the behavior of their peers (Bailey & Wolery, 1992). Many young children with ADS demonstrate an interest in their peers and immediate or delayed imitation of individual or group behavior. The target behavior must, of course, be one the child is A c a d e m i c I n t e r v e n t i o n s - D i r e c t I n s t r u c t i o n P a g e | 10 capable of imitating. Given these prerequisites, modeling has been used successfully with young children with disabilities to improve communication, motor, social and play skills. Example: At snack time, a child who does not consistently use a spoon is seated across from a favorite peer or sibling who uses a spoon correctly. An adult serves tiny portions of pudding to each child. The child modeling spoon feeding is reinforced verbally and with offers of more pudding following correct use of the spoon. Naturalistic Strategy #2: Expansions Definition: An adult responds to a child’s verbal initiations with a verbal model that is slightly more grammatically complete than what the child was using, building on the child’s present level of communicative competency. Example: For a child working on using action words, while looking at a favorite picture book, when child points and says, “Piggy!,” the adult replies, “Piggy eating!” Naturalistic Strategy #3: Naturalistic Time Delay Definition: During a familiar routine, an adult skips a step or pauses between steps and looks expectantly to the child for a set period of time (also called “wait time”). If the child initiates a response, the routine continues. If not, the adult models the expected behavior before the routine continues. A variation of this procedure, called “violation of expectancy” (Bailey & Wolery, 1992), involves the adult performing a step in the familiar routine that is out of sequence, A c a d e m i c I n t e r v e n t i o n s - D i r e c t I n s t r u c t i o n P a g e | 11 incorrect, or incomplete. This strategy has been used to increase social interaction, communicative initiations, and independence. Example # 1: Naturalistic Time Delay - While singing “This Old Man,” the adult pauses 3seconds after the phrase, “He played---?” to allow the child to respond with the appropriate number in sequence. Example # 2: Violation of Expectancy - While helping a parent set the table for a family of three, a child is given three plates but only two sets of utensils. Naturalistic Strategy #4: “Mand” Modeling Definition: “Mands” are questions that cannot be answered with yes or no, or commands that do not elicit a specific response. Mand modeling involves brief exchanges in which the adult asks a question or makes a specific request that provides the child with an opportunity to use a target communication skill. If the child gives an appropriate communicative response, the adult responds with an expansion. If the child does not provide the desired communicative response, the adult models an appropriate verbal response and looks expectantly at the child for imitation. As with other naturalistic strategies, adult initiations should relate to the child’s focus of play and follow the child’s lead. Example: A child working on using regular past-tense verbs is highly engaged with filling and dumping cornmeal at the sand table. The teacher enters and begins playing beside the child, imitating filling and pouring cornmeal from a pitcher. The teacher provides a mand: “What did you do with your cornmeal?” She looks expectantly at the child for 3 seconds, then models a A c a d e m i c I n t e r v e n t i o n s - D i r e c t I n s t r u c t i o n P a g e | 12 response, “You poured it all out.” After a couple of minutes, the teacher catches the child’s attention and gives a second mand: “What did I do with my corn meal?” The child responds, “poured it out!” The teacher expands: “I poured it out!” In the next few minutes, the sequence is repeated with mands for the child to respond to using “dumped,” “stirred,” and “shared.” Naturalistic Strategy #5: Incidental Teaching Definition: Incidental teaching is an instructional strategy in which the adult uses child initiations during ongoing activities as opportunities to respond with either a model or a request for more elaborate behavior. Incidental teaching was first developed as a way to promote generalization of communication skills from therapy to classroom settings (Hart & Risley, 1968), but it has since proven effective in teaching a broad range of skills to children with a variety of disabilities (Kaiser, Yoder, & Keetz, 1992). (For more in depth information and resources regarding incidental teaching, please refer to lesson "Incidental Teaching" in Academic Interventions unit or click here) Example: An adult joins a child engaged with a barn, farm animals, and farm equipment. The goal is for the child to demonstrate increasingly complex play behaviors. The adult imitates the child lining up farm machinery. When all machinery has been lined up, the child responds with an initiation by handing the adult a farm animal. The adult places the animal in a wagon and looks expectantly at the child, who gives the adult another animal. The adult says, “Put the horse in the wagon.” If the child complies , the adult praises the child, and play continues. If the child does not respond, the adult models the desired behavior and then waits for the next child A c a d e m i c I n t e r v e n t i o n s - D i r e c t I n s t r u c t i o n P a g e | 13 initiation to occur. In this manner, the adult guides the child through combining two or more objects in a play scheme. Response-Prompting Strategies Definition: Response prompts are adult actions that assist a child in performing a target skill or behavior. Prompts come in different forms, ranging from verbal cues, signals or gestural cues, demonstrations or models, visual cues, partial physical prompts, to fully assisted physical “putthroughs.” The effectiveness of response-prompting strategies in teaching new skills to children with disabilities is supported by a significant body of research (Wolery & Wilbers, 1994). Prompts are used to help children perform tasks that they otherwise could not or would not do. Prompts must come before the child has an opportunity to demonstrate inappropriate behavior, or the undesirable behavior may be inadvertently reinforced with adult attention. Five responseprompting strategies will be discussed: System of least prompting Chaining (task analysis) Fading Discrimination training Discrete trial training A c a d e m i c I n t e r v e n t i o n s - D i r e c t I n s t r u c t i o n P a g e | 14 Response-Prompt Strategy #1: System of Least Prompting Definition: Prompts can be thought of in a hierarchy of least-to-most assistance, proceeding from modeling to full physical assistance (Figure 2). The principle of least-to-most prompts, also known as increasing assistance or graduated guidance, involves using prompts on a continuum from least to most intrusive in terms of adult involvement. Prior to offering a prompt, the adult presents the child with the target task and provides an opportunity for an independent response. If the child does not respond, or responds incorrectly, the adult provides the least intrusive prompt and waits for a response. If the child does not respond correctly, the next level of prompt is provided, and so on, until the child responds correctly. Example: When it is time to put on a coat, the adult first puts on her own coat. After 5 seconds, if Ben does not respond, the adult points to his coat. After another 5 seconds, the adult provides a verbal prompt: “Ben, put your coat on.” Next, if Ben does not respond, the adult picks up Ben’s coat and holds it out to him. If there is still no response, the adult physically assists Ben in putting on his coat. A c a d e m i c I n t e r v e n t i o n s - D i r e c t I n s t r u c t i o n P a g e | 15 Response-Prompt Strategy #2: Chaining Definition: Chaining involves first determining the sequence in which a target task is performed (also known as task analysis). Behaviors can be chained in a forward or backward sequence. In backward chaining, the adult performs all but the last step of the task, prompting the child to finish the final step. When the child can complete the last step successfully, the adult does all but the last two steps in the sequence, prompting the child, if necessary, to perform the next-to-last step. The procedure continues in this manner until the child is able to perform the entire sequence or chain of behaviors independently. Forward chaining involves letting the child complete the first step in a skill sequence, then having the adult complete the task. After the child is able to perform the first step successfully, he is prompted to complete the second step, and so on, until he has learned the whole sequence. Example #1: Forward Chaining - Assembling a four-piece interlocking puzzle, the adult provides physical assistance to the child after an attempt is made to place the first piece. Assistance is provided for completion of remaining pieces. In subsequent trials, the adult withholds prompting until the child places two, three, and eventually four pieces independently. Example #2: Backward Chaining - Assembling a four-piece interlocking puzzle, the adult provides physical assistance to the child in placing the first three pieces, then waits for the child to place the last piece independently. In subsequent trials, assistance is gradually decreased piece by piece until the child is able to complete the entire puzzle independently. A c a d e m i c I n t e r v e n t i o n s - D i r e c t I n s t r u c t i o n P a g e | 16 (Note: For more in depth information and resources regarding chaining, please refer to lesson "Chaining" in Behavioral Interventions unit ) Response-Prompt Strategy #3: Fading Definition: Fading is the systematic reduction of a prompt. In most cases, prompts should be gradually faded as the child demonstrates success in learning the target behavior. It is important to plan the method for fading prompts. Prompts can be faded according to their intensity, magnitude, frequency, or duration. Example: In teaching Elise to identify her name, the teacher places a yellow star above the “E” in her name as it appears on a list of names. Over trials in selecting her name from the list, the star is gradually faded in color intensity until it finally blends into the white paper. In another example, the magnitude of the same prompt is faded by making the star smaller and smaller over successful trials until it disappears. To fade the frequency of the prompt, Elise’s name card could be presented without the star occasionally, then every third trial, then every other trial, until the star is no longer needed. Finally, to fade the duration of the prompt, a card with Elise’s name with the star cue could be presented for 3 seconds and then removed before Elise is given the list of names without the cue. (Note: For more in depth information and resources regarding fading, please refer to lesson "Prompting and Fading" in Behavioral Interventions mdule ) Response Prompt Strategy #4: Discrimination Training A c a d e m i c I n t e r v e n t i o n s - D i r e c t I n s t r u c t i o n P a g e | 17 Definition: Adults can teach a child to discriminate between two or more items, or to discriminate by choosing appropriate behavior for specific situations, by providing and then fading distinctive prompts. The procedure for teaching a child to discriminate between two objects involves the following steps: 1. Maximize the discrimination: choose two objects that look and sound very different from each other. 2. Remove all possible distractions. 3. Present mass trials of the first object (in isolation) until it is selected upon request with 100% accuracy. 4. Add a neutral object (distracter) and continue mass trials, requesting only the first object, until it is selected with 100% accuracy. 5. Present mass trials in which the second object (in isolation) is selected upon request with 100% accuracy. 6. Add a neutral object (distracter) and continue mass trials, requesting only the second object, until it is presented with 100% accuracy. 7. Begin mass trials with the first and second objects presented together, alternating positions, and alternating between asking for one or the other (Granspeesheh, 1995). Example: Deshon does not correctly discriminate his own toothbrush from his sister’s. The following steps could be employed in discrimination training: 1. Prompt Deshon to select his toothbrush when it is hanging alone in the toothbrush holder. A c a d e m i c I n t e r v e n t i o n s - D i r e c t I n s t r u c t i o n P a g e | 18 2. Prompt Deshon to select between his toothbrush and a pipe cleaner when both are hanging in the toothbrush holder. 3. Prompt Deshon to select his sister’s toothbrush when it is hanging alone in the toothbrush holder. 4. Prompt Deshon to select between his sister’s toothbrush and a comb when both are hanging in the toothbrush holder. 5. Prompt Deshon to select his toothbrush when it is hanging with his sister’s in the toothbrush holder. Response-Prompt Strategy #5: Discrete Trial Training Definition: According to one source (Myles & Simpson, 1990), the discrete trial training strategy (also known as clinical/prescriptive teaching or compliance training) represents a “basic instructional pattern comprising (a) a command to attend, (b) a command to perform, and (c) reinforcement for compliant behavior. Response time is provided throughout the sequence; it follows both the command to attend and the command to perform” (p. 2). The discrete trial involves a number of effective instructional strategies discussed previously, including reinforcement, modeling, system of least prompting, chaining, fading, and discrimination training. This teaching strategy places great emphasis on continuous recording of child progress (data collection). (Note: For more in depth information and resources regarding discrete trial instruction, please refer to lesson "Discrete Trial Training" in Behavioral Interventions unit) A c a d e m i c I n t e r v e n t i o n s - D i r e c t I n s t r u c t i o n P a g e | 19 Widely associated with behavioral teaching of young children with autism (Lovaas, 1981, 1987), the discrete trial format can be useful with a variety of children at different developmental levels. In addition, it can be implemented by parents and teachers, and conducted in individual and group instructional settings (Myles & Simpson, 1990). Example: The following example for a discrete trial training format is taken from Missouri’s Project ACCESS (Hawkins & Armstrong, 1996): Discrete Trial Format The Trial: 1. A verbal command is given to the child. 2. The instructor waits (planned interval, i.e., 5 seconds) for a response. 3. If the correct response is given, the child is verbally or physically reinforced. 4. If the child does not respond, or responds incorrectly, the instructor repeats the command and models the desired response (prompt) . 5. The instructor again waits (planned interval, i.e., 5 seconds) for a response. 6. If the child responds correctly, reinforcement is provided. 7. If not, the instructor repeats the command and physically prompts the child 8. to complete the task. 9. Task completion is reinforced. A c a d e m i c I n t e r v e n t i o n s - D i r e c t I n s t r u c t i o n P a g e | 20 Sample Scenario Using Discrete Trial Format to Teach Child to Follow Directions: Trial #1 Adult: “Jim, look.” Adult waits 3 seconds. Jim does not respond. Adult: “Jim, look.” Adult simultaneously raises Jim’s chin so eyes meet. Adult: “Hi there, Jim!” Trial #2 Adult: “Put the car in the tub.” Jim looks at car. (incorrect response) Adult waits 3 seconds. Adult: “Put the car in the tub.” Adult simultaneously models correct response by picking up and placing a car in the tub; waits 3 seconds. Adult: “Put the car in the tub.” Adult simultaneously assists Jim hand-over-hand to place his car in tub. Adult: “Good work, Jim!” Trial #3 Adult: “Go sit by Andrew.” Jim moves to circle, stands in center. (incorrect response) Adult waits 3 seconds. Adult: “Go sit by Andrew.” Adult simultaneously points to Andrew; waits 3 seconds. Jim sits next to Andrew . (correct response) Adult: “Good sitting, Jim!” A c a d e m i c I n t e r v e n t i o n s - D i r e c t I n s t r u c t i o n P a g e | 21 Summary The direct instruction strategies included in this unit were selected for their effectiveness in naturally occurring routines and instructional settings. In selecting the most appropriate instructional strategy for a student, teachers and parents must continually ask themselves if, in comparison with other strategies, the procedure they have chosen offers the greatest chance for success, in the shortest amount of time, in the most natural (least restrictive) setting, with the least adult assistance. Remember, research suggests that less adult direction and greater opportunity for child-initiated behavior are generally associated with increased generalization of learned skills across settings, with different materials and people. Consequently, the most adultdirected instructional strategies should be reserved for the most significantly delayed student behavior, or for critical behaviors or skills that require rapid acquisition or extinction. Identifying opportunities for direct instruction in natural settings, whether classroom or home, requires careful planning. The child’s entire day should be analyzed to identify potential opportunities for direct instruction. Also, parents and teachers need toconsider the complete hierarchy of effective instructional strategies when planning instructional opportunities. Setting the stage for success begins with arranging the physical space, using child preferences for materials and activities, structuring social aspects and routines within the child’s environment, and using peers to assist with the learning process. With these environmental supports in place, direct instruction strategies comprise an effective methodology for increasing opportunities for learning in the least restrictive setting. A c a d e m i c I n t e r v e n t i o n s - D i r e c t I n s t r u c t i o n P a g e | 22 Quiz 1. Which of the following would not be an appropriate target for the most adult-directed instructional strategies? A. Learned behaviors that need to be generalized to natural settings B. The most significantly delayed student behaviors C. Critical skills that require rapid acquisition D. Behaviors that require rapid extinction ( i.e., self-injurious behaviors) 2. Any event following a behavior that increases the probability that the behavior will occur again is considered a A. prompt B. command C. naturalistic time delay D. reinforcer 3. AJ loves to repeat favorite lines from videos all day long to anyone who will listen. He is learning to monitor his behavior during instructional activities and save “video-talk” for designated “break” times with teacher. For every subject period, A.J. can earn a minute of break time by remembering to save the “video-talk.” This is an example of what strategy? A. Behavioral momentum B. Differential reinforcement of low rate behavior (DRL) C. Expansion D. Fading 4. The strategy in which children are reinforced for making accurate statements about their intended behavior is known as A c a d e m i c I n t e r v e n t i o n s - D i r e c t I n s t r u c t i o n P a g e | 23 A. backward chaining B. response shaping C. discrimination training D. correspondence training 5. Planned episodes of brief adult-child interaction that take advantage of naturally occurring reinforcers in the course of ongoing activities and routines describe which category of instructional strategies? A. reinforcement strategies B. naturalistic strategies C. response-prompt strategies D. all of the above 6. Response prompts are behaviors that prevent a child from performing a target skill or behavior. True False 7. Increasing assistance or graduated guidance are both terms that describe which of the following strategies?. A. Modeling B. Fading C. System of least prompts D. Differential reinforcement of alternative behavior (DRA) 8. An effective strategy for teaching a child to correctly select the named object from a set of two or more would be A c a d e m i c I n t e r v e n t i o n s - D i r e c t I n s t r u c t i o n P a g e | 24 A. Differential reinforcement of incompatible behavior (DRI) B . Discrimination training C . “Mand” modeling D . Chaining 9. Which of the following is not a component of discrete trial instruction? A. Command B. Response time C. Incidental teaching D. Reinforcer