Seeing the risks and benefits with our own eyes

advertisement

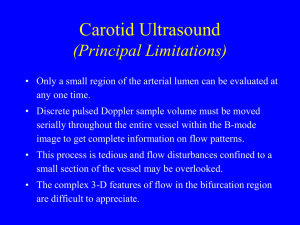

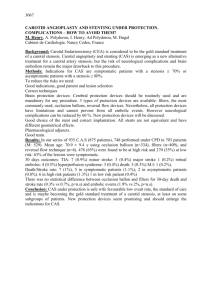

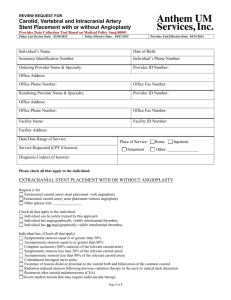

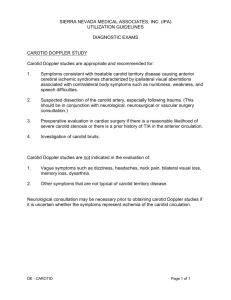

Seeing the risks and benefits with our own eyes Patrick Ryan, MD The sense of vision is an extraordinary gift and the prospect of its loss can be terrifying. The chance to see the sunrise, a child’s first steps, or a beautiful sunset are all unique experiences; one may even describe these as priceless. Mr. R was an 81-year-old gentleman with a history of CAD, PVD, and diabetes who had been experiencing declining vision due to diabetic retinopathy and glaucoma. Subsequent development of bilateral eye pain with an associated “rusty haze” to his vision raised concern for the potential of an ocular ischemic syndrome, such as retinal ischemia. Carotid artery ultrasound was obtained and revealed stenosis bilaterally: greater than 95% on the left and 70-90% on the right. Despite these findings, it was not clear that his vision loss was due to an ischemic process at all. Ultimately it was deemed that carotid stenosis was an unlikely cause of his symptoms. After several months, Mr. R stopped having eye pain, though his vision remained poor. The newly diagnosed carotid stenosis placed him at a higher risk of further vision loss, debilitating stroke, and even death. Faced with these prospects, he was referred for consideration of left carotid endarterectomy (CEA). During pre-operative evaluation his risk of major cardiac complications was estimated at 11% based on his RCRI score. Mr. R was informed of the benefits of undergoing a CEA and the potential risks of surgery including stroke, myocardial infarction and death. He elected to proceed with the surgery. Unfortunately, his post-operative course was complicated by myocardial infarction, cardiogenic shock, surgical site hematoma, vocal cord paralysis, pneumonia, urosepsis with bacteremia, and intestinal ischemia. After spending over a month in the hospital and an additional few weeks at a long-term care facility, the patient passed away. While the patient was informed and accepted the risks of this procedure, it is useful to take a closer look at the balance of risks and benefits as applied to Mr. R. Often times the potential benefit of an intervention is presented in relative terms, though this can be difficult for patients to interpret. For this reason it is preferable to describe benefit and risk in absolute terms, optimizing the chance that patients make a decision most in accordance with their wishes. On review of the data in patients with asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis, CEA can reduce risk of stroke by 30% at three years compared to usual care.1-7 When viewed in terms of absolute risk, however, the estimated potential benefit is about 3%, yielding a number needed to treat of 33 over 3 years. 4-7 This is the benefit for the average patient in the studied populations. In contrast, Mr. R’s risk of a major perioperative cardiac event (defined as: myocardial infarction, pulmonary edema, ventricular fibrillation, primary cardiac arrest, or complete heart block) was estimated to be 11%. Additionally, even though studies have shown a longer-term reduction in the risk of stroke, there is a short-term increase in morbidity due to surgery. The peri-operative risk of stroke or death at 30 days averages about 3% in the randomized studies of CEA for asymptomatic stenosis.5-6, 8 Though not a direct comparison of exact outcomes, it does suggest that on balance, CEA may not be as beneficial as it seemed on the surface for this particular patient. There were reasonable indications for obtaining the carotid ultrasound and pursuing CEA based on the degree of asymptomatic stenosis. However, when the risk-benefit data is applied at the individual level, not all cases are created equally, and thus probably should not be approached in the same manner. Perhaps during Mr. R’s perioperative evaluation, had we discussed the benefits and harms in absolute terms and the trade-off between a short-term risk increase and a long-term benefit, his decision to pursue surgery may have been different; at the least, we may have ensured that Mr. R was able to see the odds he was faced with as clearly as possible. References: 1. Abbott AA, Chambers BR, Stork JL, Levi CR, Bladin CF, Donnan GA. Embolic signals and prediction of ipsilateral stroke or transient ischemic attack in asymptomatic carotid stenosis: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Stroke 2005;36:1128–33. 2. Barnett HJM, Eliasziw M, Meldrum HE, Taylor DW. Do the facts and figures warrant a 10-fold increase in the performance of carotid endarterectomy on asymptomatic patients?. Neurology 1996;46:603–8. 3. Chambers BR, Norris JW. Outcome in patients with asymptomatic neck bruits. New England Journal of Medicine 1986;315:860–5. 4. Chambers BR, Donnan G. Carotid endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD001923. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001923.pub2. 5. Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. JAMA 1995; 273:1421. 6. Halliday A, Mansfield A, Marro J, et al. Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004; 363:1491. 7. Hobson RW 2nd, Weiss DG, Fields WS, et al. Efficacy of carotid endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid stenosis. The Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group. N Engl J Med 1993; 328:221. 8. Wolff T, Guirguis-Blake J, Miller T, Gillespie M, Harris R. Screening for Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Stenosis. Evidence Synthesis No. 50. AHRQ Publication No. 08-05102-EF-1. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, December 2007.