A Brief History of the Cold War

advertisement

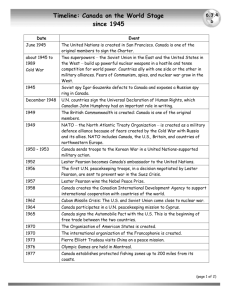

A Brief History of the Cold War The Cold War began even before the hot war was over. Until the Trinity device was successfully tested on July 16, 1945, the Army consistently advised President Roosevelt that he could not depend upon the atomic bomb. Throughout the war the United States believed that victory depended upon the support of the Soviet Union to fight Hitler in the West and Japan in the East. Despite the February 1945 agreements at Yalta that free elections would be held in all of the liberated European countries, Stalin apparently never intended to keep his word. By mid-March 1945, Winston Churchill wrote to Roosevelt that everything in Europe supposedly settled at Yalta had broken down. In March 1946, Churchill delivered his famous "iron curtain" speech. By 1947, Western Europe was on the verge of disintegration and the Soviet Union was ready to take advantage of the situation. The Truman Administration concluded that only by building up an effective atomic arsenal could it convince the Soviet leaders that they could not continue to prey on struggling nations and provoke another world war. Immediately after the war, the nuclear weapons production complex with production plants, laboratories, and administrative offices scattered in thirteen states across the continent, had an unclear future. Employment levels dropped precipitously at Hanford. Many officials believed that the hastily constructed plants would be shut down at the end of the war, their mission accomplished. Amidst this uncertainty, the Atomic Energy Act of 1946 was passed, creating a five person Atomic Energy Commission responsible for managing the former Manhattan Project operations. The Act also called for the development of atomic energy toward "improving the public welfare, increasing the standard of living, strengthening free competition in private enterprise, and promoting world peace." The newly formed Atomic Energy Commission took steps to implement this mandate. First, the Commission established a national laboratory system that could provide universities in different areas of the country with access to nuclear reactors and high energy accelerators. These enormously expensive tools were essential for universities to pursue the next steps in research in the fundamentals of nuclear science, its application in biomedical sciences and other fields, and training of young scientists. In addition, the new Atomic Energy Commission launched a "Plowshare Program" with projects that involved peaceful applications of the atomic energy such as mining, oil drilling, and large-scale engineering projects such as canal, harbor, and dam construction. The post-war lull for the weapons production plants was soon over. In August 1949, the Soviet Union tested its first nuclear weapon and was suspected of developing a hydrogen bomb. The Soviet's detonation of "Little Joe" sparked a renewed sense of national urgency that was reinforced in 1950 by the outbreak of the Korean War. Soon, the country would be engaged in the largest construction project in peacetime history, vastly expanding the facilities for producing special nuclear materials and weapons. In January 1950, President Truman made the controversial decision to continue and intensify research and production of thermonuclear weapons. At the time, David Lilienthal, chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, had strong reservations about pursuing the "Super" or thermonuclear bomb. However, on July 25, 1950, President Harry Truman wrote to Crawford H. Greenewalt, President of E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, asking DuPont to undertake the design, construction and operation of a new site to produce plutonium and tritium, a necessary ingredient for the thermonuclear bomb. Because of the increasing range of Soviet aircraft, the Commission ruled out expanding Hanford but preferred distant sites in the South and Ohio River region. Thus began the vast expansion of the nuclear weapons complex that eventually had operations in some 32 states. The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989 and end of the Cold War prompted James Watkins, then Secretary of Energy, to initiate "tiger teams" to perform comprehensive environmental, safety, and health assessments and begin the environmental clean up of the sites. Within five years, this effort became the world's largest environmental clean up program as the department realized the magnitude of the environmental problems created over four decades when production of nuclear weapons took priority. Today most of the old nuclear production facilities have been shut down. The entire complex is engaged in an ambitious clean up program and weighing future uses of the properties. With most of the Manhattan Project and Cold War facilities slated for decommissioning and disposal over the next few years, it is particularly important to assess their significance in the history of the United States and the world and work to preserve some of this history through the properties, artifacts and oral histories before it is too late. http://www.atomicheritage.org/index.php/component/content/article/42-resources-tab-/67-a-briefhistory-of-the-cold-war.html