Jungle Gateway _ACT reading practice

advertisement

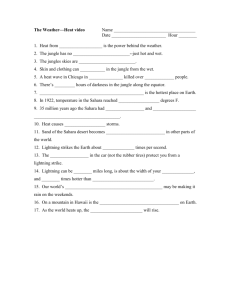

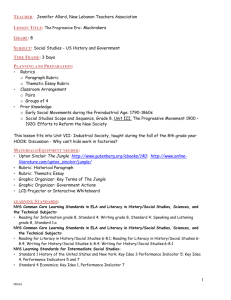

Lee-Chin English 3 The Jungle Gateway Activity ACT Reading Practice and Background to The Jungle The Assignment: Read the below information about the Reading section on the ACT from the ACT’s own website. After you read this information, take the sample “Social Science” passage which has four multiple choice questions. Then, read the passage by Upton Sinclair and write six multiple choice questions based on the reading. For each question you must label the kind of question you’ve created using the types listed below (determine main ideas; locate and interpret significant details etc. )You may work in groups of three to complete this assignment. Complete this assignment in google docs named “Last Names Gateway Jungle_ACT practice” and share it with me at clee-chin@maine207.org Reading Test Description Content Covered by the ACT Reading Test The Reading Test is based on four types of reading selections: social studies, natural sciences, prose fiction, and humanities. The Social Studies/Sciences subscore is based on the questions on the social studies and natural sciences passages, and the Arts/Literature subscore is based on the questions on the prose fiction and humanities passages. Social Studies (25%). Questions in this category are based on passages in the content areas of anthropology, archaeology, biography, business, economics, education, geography, history, political science, psychology, and sociology. Natural Sciences (25%). Questions in this category are based on passages in the content areas of anatomy, astronomy, biology, botany, chemistry, ecology, geology, medicine, meteorology, microbiology, natural history, physiology, physics, technology, and zoology. Prose Fiction (25%). Questions in this category are based on intact short stories or excerpts from short stories or novels. Humanities (25%). Questions in this category are based on passages from memoirs and personal essays and in the content areas of architecture, art, dance, ethics, film, language, literary criticism, music, philosophy, radio, television, and theater. The Reading Test is a 40-question, 35-minute test that measures your reading comprehension. You're asked to read four passages and answer questions that show your understanding of: what is directly stated statements with implied meanings Specifically, questions will ask you to use referring and reasoning skills to: determine main ideas locate and interpret significant details understand sequences of events make comparisons comprehend cause-effect relationships determine the meaning of context-dependent words, phrases, and statements draw generalizations analyze the author's or narrator's voice and method The test comprises four prose passages that are representative of the level and kind of reading required in firstyear college courses; passages on topics in social studies, natural sciences, prose fiction, and the humanities are included. Each passage is accompanied by a set of multiple-choice test questions. These questions do not test the rote recall of facts from outside the passage, isolated vocabulary items, or rules of formal logic. Instead, the test focuses on the complementary and supportive skills that readers must use in studying written materials across a range of subject areas. Lee-Chin English 3 The Jungle Gateway Activity ACT Reading Practice and Background to The Jungle Reading: Social Sciences Sample Passage and Items Sample Passage 1: Social Sciences If we are to understand the politics of a nation, we must understand the issues people care about and the underlying images of the good society and how to achieve it that shape their opinions. Citizens in different nations differ as to the importance they attach to various policy outcomes. In some societies private property is highly valued, in others communal possessions are the rule. Some goods are valued by nearly everyone, such as material welfare, but societies differ nevertheless: some emphasize equality and minimum standards for all, while others emphasize the opportunity to move up the economic ladder. Some cultures put more weight on welfare and security, others value liberty and procedural justice. Moreover, the combination of learned values, strategies, and social conditions will lead to quite different perceptions about how to achieve desired social outcomes. One study showed that 73 percent of the Italian Parliament strongly agreed that a government wanting to help the poor would have to take from the rich in order to do it. Only 12 percent of the British Parliament took the same strong position, and half disagreed with the idea that redistribution was laden with conflict. Similarly, citizens and leaders in preindustrial nations disagree about the mixture of government regulation and direct government investment in the economy necessary for economic growth. Political cultures may be consensual or conflictual on issues of public policy and on their views of legitimate governmental and political arrangements. In a consensual political culture citizens tend to agree on the appropriate means of making decisions and tend to share views of what the major problems of the society are and how to solve these. In more conflictual cultures the citizens are sharply divided, often on both the legitimacy of the regime and solutions to major problems. In several recent studies of citizens' attitudes in industrial societies, respondents in different countries were asked to locate their political positions on a ten-point scale ranging from extreme left to extreme right. Figure 1 Patterns of Left-Right Distributions of Opinion in Five Countries: Citizens' Self-Placement in the Mid-1970s Lee-Chin English 3 The Jungle Gateway Activity ACT Reading Practice and Background to The Jungle The differences and patterns can be seen in Figure 1. In the top part of the figure we see the United States, Britain, and Germany. In each of these countries the distribution is that of a normal curve. Most of the respondents are concentrated in the center and very few place themselves at the extreme right or extreme left. The United States has the most consensual of these distributions, with nearly half the respondents locating themselves at the center. At the bottom of the figure we see the distributions for France and Italy. although the center is still the most common position, their political cultures are more conflictual than those of the three countries above. Fewer citizens locate themselves at the center—only about one-third in France do so. And, as we might expect from the substantial strength of Communist parties in France and Italy, many citizens place themselves at the extreme left. These more conflictual distributions in the political culture both encourage and reflect the more intense political debates in these countries, and have been associated with dispute over the legitimacy of the regime as well as disagreements on political issues. When a country like Italy or France is deeply divided in political attitudes and values we speak of the distinctive groups as political subcultures, which may share common national sentiments and loyalties, but disagree on basic issues, ideologies, and the like. The term political subculture may also be applied to groups less opposed to one another, as in Austria and the Netherlands. In the latter countries, such groups as Catholics, Protestants, liberals, and socialists have distinctive points of view on political matters, affiliate themselves with different political parties and interest groups, have separate newspapers, and even separate social clubs and sport groups. Nonetheless, relationships between these groups have been relatively amicable in recent years, unlike the intense and violent conflict between political subcultures in Northern Ireland. From Gabriel A. Almond and G. Bingham Powell, Jr., Comparative Politics Today: A World View. © 1984 by Gabriel A. Almond and G. Bingham Powell, Jr. Sample Items for Passage 1 1. The passage argues that the politics of a nation are determined by: A. the amount and kind of economic activity engaged in by a society. B. a consensus of national sentiments and loyalties. C. the degree to which the interests of a nation conflict with those of other nations. D. the opinions of citizens about what policies are best for their society. 2. The passage suggests that political subcultures exist in societies in which: I. there is a high degree of political consensus. II. citizens disagree violently on basic political issues. III. disagreement between political parties is generally amicable. A. I only B. II only C. III only D. I and III only E. II and III only 3. According to Figure 1, which nation reports the greatest number of citizens who consider their political orientation to be on the extreme right? A. France B. Italy C. United Kingdom D. United States 4. A nation in which two political parties publish newspapers which criticize each other's ideas for instituting reform in welfare programs can most likely be considered a: Lee-Chin English 3 The Jungle Gateway Activity ACT Reading Practice and Background to The Jungle A. B. C. D. conflictual culture with harshly opposed political subcultures. conflictual culture with amicable political subcultures. consensual culture with amicable political subcultures. conflictual culture with limited freedom of the press. Attack on the Meatpackers (1906) Upton Sinclair Introduction Today we often take for granted the government legislation that protects our health. Investigative reports on television even go to great lengths to show us when the health guidelines are being violated. In other words, we assume the food available for us to eat is safe. The federal government, however, was not always so involved in such issues. You may want to review the term “progressivism” before analyzing this excerpt from Upton Sinclair's The Jungle. Questions to Activate Your Thinking While You Read 1. Define progressivism. 2. What do you find most surprising in Upton Sinclair's account of the meatpacking industry around the turn of the century? Why? 3. What do you think was Sinclair's purpose for writing this piece? 4. How do you think readers reacted to The Jungle when it first came out? 5. What connection do you see between the public's reading The Jungle and subsequent progressive legislation, like the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act, which were passed within six months of its publication? 6. Do you think this legislation would have passed without the public attention these issues received after the publication of articles and books like this one? Why or why not? 7. What does the publication of The Jungle tell you about the progressive movement? Source . . . And then there was the condemned meat industry, with its endless horrors. The people of Chicago saw the government inspectors in Packingtown, and they all took that to mean that they were protected from diseased meat; they did not understand that these hundred and sixty-three inspectors had been appointed at the request of the packers, and that they were paid by the United States government to certify that all the diseased meat was kept in the state. They had no authority beyond that; for the inspection of meat to be sold in the city and state the whole force in Packingtown consisted of three henchmen of the local political machine! . . . Lee-Chin English 3 The Jungle Gateway Activity ACT Reading Practice and Background to The Jungle And then there was "potted game" and "potted grouse," "potted ham," and "deviled ham"— devyled, as the men called it. "De-vyled" ham was made out of the waste ends of smoked beef that were too small to be sliced by the machines; and also tripe, dyed with chemicals so that it would not show white, and trimmings of hams and corned beef, and potatoes, skins and all, and finally the hard cartilaginous gullets of beef, after the tongues had been cut out. All this ingenious mixture was ground up and flavored with spices to make it taste like something. Anybody who could invent a new imitation had been sure of a fortune from old Durham, said Jurgis's informant, but it was hard to think of anything new in a place where so many sharp wits had been at work for so long; where men welcomed tuberculosis in the cattle they were feeding, because it made them fatten more quickly; and where they bought up all the old rancid butter left over in the grocery stores of a continent, and "oxidized" it by a forced-air process, to take away the odor, rechurned it with skim milk, and sold it in bricks in the cities! . . . There were the men in the pickle rooms, for instance, where old Antanas had gotten his death; scarce a one of these that had not some spot of horror on his person. Let a man so much as scrape his finger pushing a truck in the pickle rooms, and he might have a sore that would put him out of the world; all the joints of his fingers might be eaten by the acid, one by one. Of the butchers and floorsmen, the beef boners and trimmers, and all those who used knives, you could scarcely find a person who had the use of his thumb; time and time again the base of it had been slashed, till it was a mere lump of flesh against which the man pressed the knife to hold it. The hands of these men would be criss-crossed with cuts, until you could no longer pretend to count them or to trace them. They would have no nails,—they had worn them off pulling hides; their knuckles were swollen so that their fingers spread out like a fan. There were men who worked in the cooking rooms, in the midst of steam and sickening odors, by artificial light; in these rooms the germs of tuberculosis might live for two years, but the supply was renewed every hour. There were the beef luggers, who carried two-hundred-pound quarters into the refrigerator cars, a fearful kind of work, that began at four o'clock in the morning, and that wore out the most powerful men in a few years. There were those who worked in the chilling rooms, and whose special disease was rheumatism; the time limit that a man could work in the chilling rooms was said to be five years. There were the wool pluckers, whose hands went to pieces even sooner than the hands of the pickle men; for the pelts of the sheep had to be painted with acid to loosen the wool, and then the pluckers had to pull out this wool with their bare hands, till the acid had eaten their fingers off. There were those who made the tins for the canned meat, and their hands, too, were a maze of cuts, and each cut represented a chance for blood poisoning. Some worked at the stamping machines, and it was very seldom that one could work long there at the pace that was set, and not give out and forget himself, and have a part of his hand chopped off. There were the "hoisters," as they were called, whose task it was to press the lever which lifted the dead cattle off the floor. They ran along upon a rafter, peering down through the damp and the steam, and as old Durham's architects had not built the killing room for the convenience of the hoisters, Lee-Chin English 3 The Jungle Gateway Activity ACT Reading Practice and Background to The Jungle at every few feet they would have to stoop under a beam, say four feet above the one they ran on, which got them into the habit of stooping, so that in a few years they would be walking like chimpanzees. Worst of any, however, were the fertilizer men, and those who served in the cooking rooms. These people could not be shown to the visitor—for the odor of a fertilizer man would scare away any ordinary visitor at a hundred yards, and as for the other men, who worked in tank rooms full of steam, and in some of which there were open vats near the level of the floor, their peculiar trouble was that they fell into the vats; and when they were fished out, there was never enough of them left to be worth exhibiting—sometimes they would be overlooked for days, till all but the bones of them had gone out to the world as Durham's Pure Leaf Lard! . . . There was never the least attention paid to what was cut up for sausage; there would come all the way back from Europe old sausage that had been rejected, and that was mouldy and white—it would be dosed with borax and glycerine, and dumped into the hoppers, and made over again for home consumption. There would be meat that had tumbled out on the floor, in the dirt and sawdust, where the workers had tramped and spit uncounted billions of consumption germs. There would be meat stored in great piles in rooms; and the water from leaky roofs would drip over it, and thousands of rats would race about on it. It was too dark in these storage places to see well, but a man could run his hand over these piles of meat and sweep off handfuls of the dried dung of rats. These rats were nuisances, and the packers would put poisoned bread out for them, they would die, and then rats, bread, and meat would go into the hoppers together. This is no fairy story and no joke; the meat would be shovelled into carts, and the man who did the shoveling would not trouble to lift out a rat even when he saw one—there were things that went into the sausage in comparison with which a poisoned rat was a tidbit. There was no place for the men to wash their hands before they ate their dinner, and so they made a practice of washing them in the water that was to be ladled into the sausage. There were the butt-ends of smoked meat, and the scraps of corned beef, and all the odds and ends of the waste of the plants, that would be dumped into old barrels in the cellar and left there. Under the system of rigid economy which the packers enforced, there were some jobs that it only paid to do once in a long time, and among these was the cleaning out of the waste barrels. Every spring they did it; and in the barrels would be dirt and rust and old nails and stale water—and cart load after cart load of it would be taken up and dumped into the hoppers with fresh meat, and sent out to the public's breakfast. Some of it they would make into "smoked" sausage—but as the smoking took time, and was therefore expensive, they would call upon their chemistry department, and preserve it with borax and color it with gelatine to make it brown. All of their sausage came out of the same bowl, but when they came to wrap it they would stamp some of it "special," and for this they would charge two cents more a pound. . . . And then the editor wanted to know upon what ground Dr. Schliemann asserted that it might be possible for a society to exist upon an hour's toil by each of its members. "Just what," answered Lee-Chin English 3 The Jungle Gateway Activity ACT Reading Practice and Background to The Jungle the other, "would be the productive capacity of society if the present resources of science were utilized, we have no means of ascertaining; but we may be sure it would exceed anything that would sound reasonable to minds inured to the ferocious barbarities of Capitalism. After the triumph of the international proletariat, war would of course be inconceivable; and who can figure the cost of war to humanity—not merely the value of the lives and the material that it destroys, not merely the cost of keeping millions of men in idleness, of arming and equipping them for battle and parade, but the drain upon the vital energies of society by the war-attitude and the war-terror, the brutality and ignorance, the drunkenness, prostitution, and crime it entails, the industrial impotence and the moral deadness? Do you think that it would be too much to say that two hours of the working time of every efficient member of a community goes to feed the red fiend of war?" And then Schliemann went on to outline some of the wastes of competition: the losses of industrial warfare; the ceaseless worry and friction; the vices—such as drink, for instance, the use of which had nearly doubled in twenty years, as a consequence of the intensification of the economic struggle; the idle and unproductive members of the community, the frivolous rich and the pauperized poor; the law and the whole machinery of repression; the wastes of social ostentation, the milliners and tailors, the hairdressers, dancing masters, chefs and lackeys. "You understand," he said, "that in a society dominated by the fact of commercial competition, money is necessarily the test of prowess, and wastefulness the sole criterion of power. So we have, at the present moment, a society with, say, thirty per cent of the population occupied in producing useless articles, and one per cent occupied in destroying them. . . . And then there were official returns from the various precincts and wards of the city itself! Whether it was a factory district or one of the "silk-stocking" wards seemed to make no particular difference in the increase; but one of the things which surprised the [Socialist] party leaders most was the tremendous vote that came rolling in from the stockyards. Packingtown comprised three wards of the city, and the vote in the spring of 1903 had been five hundred, and in the fall of the same year, sixteen hundred. Now, only a year later, it was over sixty-three hundred—and the Democratic vote only eighty-eight hundred! There were other wards in which the Democratic vote had been actually surpassed, and in two districts, members of the state legislature had been elected. Thus Chicago now led the country; it had set a new standard for the party, it had shown the workingmen the way! —So spoke an orator upon the platform; and two thousand pairs of eyes were fixed upon him, and two thousand voices were cheering his every sentence. The orator had been the head of the city's relief bureau in the stockyards, until the sight of misery and corruption had made him sick. He was young, hungry-looking, full of fire; and as he swung his long arms and beat up the crowd, to Jurgis he seemed the very spirit of the revolution. "Organize! Organize! Organize!"— Lee-Chin English 3 The Jungle Gateway Activity ACT Reading Practice and Background to The Jungle that was his cry. He was afraid of this tremendous vote, which his party had not expected, and which it had not earned. "These men are not Socialists!" he cried. "This election will pass, and the excitement will die, and people will forget about it; and if you forget about it, too, if you sink back and rest upon your oars, we shall lose this vote that we have polled today, and our enemies will laugh us to scorn! It rests with you to take your resolution—now, in the flush of victory, to find these men who have voted for us, and bring them to our meetings, and organize them and bind them to us! We shall not find all our campaigns as easy as this one. Everywhere in the country tonight the old party politicians are studying this vote, and setting their sails by it; and nowhere will they be quicker or more cunning than here in our own city. Fifty thousand Socialist votes in Chicago means a municipal-ownership Democracy in the spring! And then they will fool the voters once more, and all the powers of plunder and corruption will be swept into office again! But whatever they may do when they get in, there is one thing they will not do, and that will be the thing for which they were elected! They will not give the people of our city municipal ownership—they will not mean to do it, they will not try to do it; all that they will do is give our party in Chicago the greatest opportunity that has ever come to Socialism in America! We shall have the sham reformers self-stultified and self-convicted; we shall have the radical Democracy left without a lie with which to cover its nakedness! And then will begin the rush that will never be checked, the tide that will never turn till it has reached its flood—that will be irresistible, overwhelming—the rallying of the outraged workingmen of Chicago to our standard! And we shall organize them, we shall drill them, we shall marshal them for the victory! We shall bear down the opposition, we shall sweep it before us—and Chicago will be ours! Chicago will be ours! CHICAGO WILL BE OURS!" The End