A parody of the speech in praise of marriage

advertisement

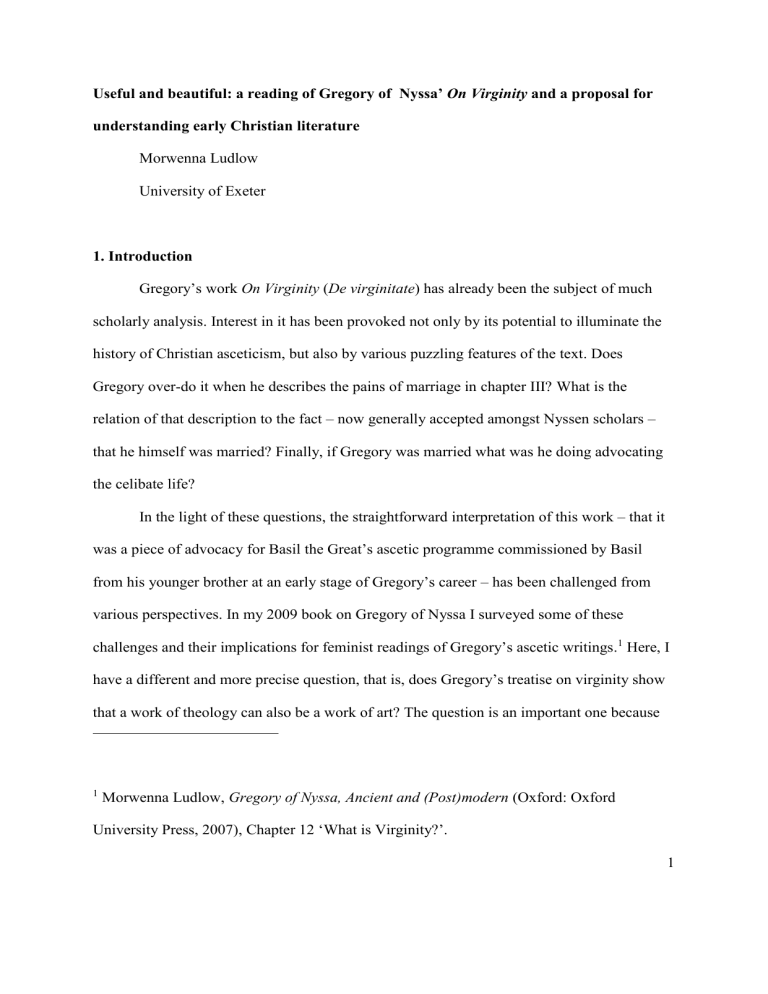

Useful and beautiful: a reading of Gregory of Nyssa’ On Virginity and a proposal for understanding early Christian literature Morwenna Ludlow University of Exeter 1. Introduction Gregory’s work On Virginity (De virginitate) has already been the subject of much scholarly analysis. Interest in it has been provoked not only by its potential to illuminate the history of Christian asceticism, but also by various puzzling features of the text. Does Gregory over-do it when he describes the pains of marriage in chapter III? What is the relation of that description to the fact – now generally accepted amongst Nyssen scholars – that he himself was married? Finally, if Gregory was married what was he doing advocating the celibate life? In the light of these questions, the straightforward interpretation of this work – that it was a piece of advocacy for Basil the Great’s ascetic programme commissioned by Basil from his younger brother at an early stage of Gregory’s career – has been challenged from various perspectives. In my 2009 book on Gregory of Nyssa I surveyed some of these challenges and their implications for feminist readings of Gregory’s ascetic writings.1 Here, I have a different and more precise question, that is, does Gregory’s treatise on virginity show that a work of theology can also be a work of art? The question is an important one because 1 Morwenna Ludlow, Gregory of Nyssa, Ancient and (Post)modern (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), Chapter 12 ‘What is Virginity?’. 1 interpretations of early Christian literature which emphasise rhetorical style or artful composition, have tended to downplay their theological content or have implied that artful form is mere decoration or is even in tension with the theological content. Scholarship on Augustine has been a partial exception to this trend and the situation is perhaps changing more generally; nevertheless, I think that there is still a need for a strong case to be made that early Christian literature can be both highly artful and also theological in its fullest sense. In order to answer my question ‘Can theology be art?’, one of my tactics will be to examine Gregory’s creation of a particular rhetorical or poetic voice through his manipulation of certain stock themes from classical literature. In the first part of this paper I will therefore analyse three themes in particular from Gregory’s work De virginitate: first, Gregory’s account of the ills of marriage; secondly, references to choruses of various kinds, and thirdly, references to water. I will hope to show that, regardless of our opinions about the success of Gregory’s enterprise, De virginitate is undoubtedly highly artful and, furthermore, employs a range of reference hitherto unrecognised by patristics scholars. In the second part of the paper, I will set out a broader argument which will analyse the concepts of rhetoric and art in the classical and late antique worlds. Modern readers – taken in equally by ancient attacks on bad rhetoric and romantic notions of high art – have tended to narrow both concepts and have therefore been prone either to dismiss or ignore the rhetorical and artistic aspects of early Christian literature. I will suggest that, by situating Gregory of Nyssa (and his fellow Christian authors) in a context in which rhetoric could be seen as an ally to philosophy, in which rhetors spoke of their skills in terms of poetry and in which the arts could be praised for being both useful and beautiful, we will emerge with a better understanding both of Gregory’s treatise and of the late antique notions of art and rhetoric. So, I will conclude that yes, Gregory’s work is both art and theology and that there is a profound complementarity 2 between the form and the subject of the treatise. Gregory explicitly defends virginity and (somewhat surprisingly) marriage; he also implicitly defends his use of artful rhetoric in their defence. But I will also conclude that Gregory’s defence of each of these things – virginity, marriage, rhetoric – is couched in terms of the common good, a conclusion which will upset some preconceived notions of rhetoric and art in late antiquity. 2. The ills of marriage and the ekphrasis of the bride (De virginitate III:3) Technically speaking, an epithalamium was a song, poem or speech made at the entrance of the bridal chamber – the thalamos – at the point just before the bride and groom were due to enter and the marriage would be consummated. The term is also used more generally, however, to describe a range of poetry and prose forms which refer to a wedding. The basic function of these genres is praise: not just praise of the bride and groom themselves, but also praise of the couple’s families, of the institution of marriage and of a god or gods associated with marriage. So, for example, in his treatise on rhetoric Menander Rhetor recommends that an epithalamium should begin with a preface and next discuss ‘the God of marriage and… the proposition that marriage is a good thing’. The speech should then continue with formal praises (encomia) of the couple’s families and of the bridal pair themselves. Finally, there should follow a description of the bridal chamber, before the speech concludes with a prayer for children.2 The Epithalamium for Severus, by the fourth 2 Menander Rhetor, Treatise II.vi The Epithalamium, in D. A. Russell and N. G. Wilson (edd. and trr.) Menander Rhetor (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981), p.135ff; see also PseudoDionysius Rhetor, Procedure for Marriage Speeches, ibid. p.365ff. 3 century Athenian orator Himerius, has the same themes, but ordered slightly differently: a prooimion, a section on the question of marriage, the encomium of the spouses and then an additional part of the encomium of the bride, specifically dedicated to a description (ekphrasis) of her beauty.3 Importantly, however, these themes are not restricted to rhetoric, but appear in a long tradition of epithalamic poetry in both Greek and Latin. So far as one can tell from the fragmentary evidence, Sappho in the 6th century BCE dealt with these themes in some poems whose dramatic setting was a wedding.4 Moving on three centuries, Theocritus’ Poem 18 on the wedding of Helen to Menelaus has a narrative introduction, followed by the praise of the groom and bride; it concludes with prayers for healthy children as the fictional choir of maidens withdraws from the wedding-chamber.5 Finally, one of the great Latin poets of the Roman Republic, Catullus, set his Poem 61 at a wedding: it begins with an introduction, before praising the god Hymenaeus, the bride and the groom in turn; it then describes the bridal bed, and prays to Venus for children to result from the imminent consummation of the 3 Himerius, Or. 9. Epithalamium for Severus 6 tr. Robert J. Penella in The Man and the Word, the Orations of Himerius (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), pp.145-55. 4 Greek text and English translation: Greek Lyric, Volume I: Sappho and Alcaeus ed. and tr. David A. Campbell, Loeb Classical Library 142 (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1982). 5 Theocritus, Select poems ed. K.J. Dover (London : Macmillan, 1971); English translation: Theocritus, Idylls, tr. Anthony Verity (Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2002) pp.59-60. 4 marriage.6 It is important to note that both rhetorical textbooks and actual examples of rhetorical epithalamia are very aware of these continuities between poetry and rhetoric. Thus, for example, Himerius says of the first part of his speech, ‘these… are the beauties of marriage; the poets sing of them, and it is customary to rehearse them at the bridal chamber’.7 Menander advises, ‘There is much information.. in poets and prose-writers, from which you can draw supplies. You should also quote from Sappho’s love poems, from Homer, and from Hesiod…’.8 Besides the continuities of theme, a further notable feature of all these epithalamia, however, is the way in which the author presents his or her narrators as actual participants and close observers in the wedding-feast. The verses I have mentioned by Sappho, Theocritus and Catullus are written as hymns supposedly sung by choirs of young men or women participating in the rituals of the wedding. A similar fiction structures wedding speeches: for example, Himerius concludes, ‘But tell me, where are the choruses of maidens, where are the choruses of young bachelors? My eloquence leaves the rest of the festivities to you…. I myself shall stand next to the bedroom and pray to Fortune, to Eros and the gods of procreation…’.9 Such fictional presence not only cleverly draws the audience into the dramatic scenario imagined by the poem, but it also gives the poet or rhetor an excuse for 6 Catullus, The Complete Poems ed. and tr. Guy Lee (Oxford : Oxford University Press, 1998) pp.57-70. 7 Himerius Or. 9:12, tr. Penella, p.150. 8 Menander Rhetor, Treatise II.vi The Epithalamium, trr. Russell and Wilson, p.141. 9 Himerius Or. 9:21, tr. Penella, p.155. 5 vivid description: he or she can describe the beauty of the bride because he or she can supposedly actually see her.10 Menander even cautions his pupils against giving too much detail in case it should suggest that the rhetor had the kind of inside information that would bring a sheltered young bride into disrepute.11 The rhetor Himerius, however, not only selfconsciously picks up on Sappho’s poetic language, but uses his fictional presence at the door of the bed-chamber as the pretext for a particularly fine description: Very well, we shall now conduct my oration into the bedroom and persuade it to encounter the bride’s beauty: ‘O beautiful woman, O graceful woman’ – for Lesbian accolades suit you – rosy-ankled Graces and golden Aphrodite play with you, the Hours supply you with the meadows’ flowers…. [Desire] takes a position in your eyes, sending out from them its irresistible flames. [Love] reddens your cheeks with modesty more than nature colours rosebuds, when in springtime they split open in their maturity and show the redness at the tops of their petals. Persuasion settles on your lips and lets its charm trickle out along 10 Sappho famously describes the bride as intact as an apple on the highest branch, or like an untrodden hyacinth (Denys Page, Sappho and Alcaeus. An Introduction to the Study of Ancient Lesbian Poetry (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1955) p.121; cf. p.123 on the groom; see also Catullus Poem 61 and Poem 62 in The Complete Poems ed. and tr. Lee pp.57-74. 11 Menander Rhetor, Treatise II.vi The Epithalamium, trr. Russell and Wilson, p.145. 6 with your words. Many curls appear on your head, reddish and parted on your brow…12 In other words, then, the narrator’s fictional presence at the wedding is tightly connected to the very prevalent use in these texts of ekphrasis, that is, a highly artful mode of speech which describes in sensory (usually visual) terms an object, person or scene which is not present to the audience.13 It is in this literary context that we should read Gregory’s description of the young bride in De virginitate III: as Michel Aubineau has noted,14 here Gregory is not only launching into a description of the ‘pains of marriage’, which was a relatively common Greek philosophical theme, but one of the tactics he uses is to echo the kind of ekphrasis of the bride given by rhetors such as Himerius. Gregory writes: 12 Himerius Or. 9:19, tr. Penella, p.153-4; the phrase ‘O beautiful woman, o graceful woman’ is taken by scholars to be a quotation from an otherwise lost work of Sappho: fragment 108 in Greek Lyric, Volume I: Sappho and Alcaeus, ed. and tr.Campbell, pp.134-5. 13 For a wide-ranging discussion of ekphrasis which argues that in the classical world the form was not restricted to the vivid description of an art-work see: Ruth Webb, Ekphrasis, Imagination and Persuasion in Ancient Rhetorical Theory and Practice (Farnham: Ashgate, 2009), especially pp.1-5. 14 Grégoire de Nysse, Traité de la Virginité ed., tr. & comm. Michel Aubineau, Sources Chrétiennes, 119 (Paris: Editions du Cerf, 1966), p.89-90 (on the use of ekphrasis) and p94-6 (on diatribe on the pains of marriage). 7 Whenever the husband looks at the beloved face, that moment the fear of separation accompanies the look. If he listens to the sweet voice, the thought comes into his mind that some day he will not hear it. Whenever he is glad with gazing on her beauty, then he shudders most with the presentiment of mourning her loss. When he marks all those charms which to youth are so precious and which the thoughtless seek for, the bright eyes beneath the lids, the arching eyebrows, the cheek with its sweet and dimpling smile, the natural red that blooms upon the lips, the gold-bound hair shining in many-twisted masses on the head, and all that transient grace, then, though he may be little given to reflection, he must have this thought also in his inmost soul that some day all this beauty will melt away and become as nothing, turned after all this show into noisome and unsightly bones, which wear no trace, no memorial, no remnant of that living bloom.15 Aubineau sees Gregory’s method as the skilful, yet somewhat heartless employment of a range of rhetorical devices and a mélange of tropes appropriate to different situations.16 Thus he sees Gregory as blending the ekphrasis of the bride from an epithalamium with elements 15 Gregory of Nyssa, De virg. III.3, tr. William Moore, NPNF series 2, vol. V, p.346 (GNO VIII/1:259:10-27). 16 Aubineau recognizes Gregory’s skill as that of a ‘grand artiste’! (Grégoire de Nysse Traité de la Virginité: p.91): ‘Voila, sans conteste, un artiste, qui sait jouer pour séduire son lecteur de toutes ses ressources…’ (ibid. p.93). 8 from funeral speeches.17 He accuses Gregory of using too much technique: even the vivid details that shock the modern reader can be attributed to Gregory’s ‘servile obedience’ to rhetorical precepts.18 According to Aubineau, one finds in these pages on marriage not Gregory’s personal response to its trials, but rather a purely rhetorical exercise.19 By contrast, I prefer to interpret this passage not as a tasteless and crudely mechanical mixing of genres, but rather as a systematic attempt to stand the epithalamium genre on its head. Gregory’s most obvious method, as we have seen, is to reverse the ekphrasis of the bride – but he also goes beyond this.20 For example, Gregory mentions the birth of children and describes the marriage chamber (both themes of epithalamia, as we have seen). But alas, in De virginitate the birth of a child only brings death to the young wife and thus the 17 Aubineau, Grégoire de Nysse Traité de la Virginité, p.90. 18 ‘Bien des détails qui nous déconcertent ou nous choquent, s'expliquent par une obéissance servile à des préceptes qui n'engage pas profondément l'auteur’ (Aubineau, Grégoire de Nysse Traité de la Virginité, p.90). See also ibid. p.89: ‘une preciosité cultivée avec trop de complaisance’ and p.93: ‘Là encore, Grégoire sacrifie aux règles d'un genre’. 19 ‘Il ne faut voir dans ces pages sur le mariage qu'un pur exercice dans le meilleur style des progumnasmata des écoles de rhétorique’ (Aubineau, Grégoire de Nysse Traité de la Virginité, p.94); see also p.91. 20 Aubineau is careful to note that chapter III is merely the most vivid example of Gregory’s use of rhetoric, not its only use; however, he does not analyse the use of rhetoric throughout the treatise as an organic whole: (Grégoire de Nysse Traité de la Virginité, p.87). 9 wedding-chamber (thalamos) becomes the room of death (thanatos).21 The groom is even described cursing those who arranged his marriage for him – again a reversal of a standard marriage-theme, the praise of the couple’s families.22 In a reprise of the ekphrasis of the bride, Gregory describes a bride who is widowed very young: again, he reverses the stock motifs, describing how it is death, not her husband, who ‘takes off her bridal ornaments’ and how her waiting women sing dirges, rather than marriage-hymns.23 Of course, this reverseepithalamium technique occurs in funeral epigrams24 and was used by many funeral speeches. Gregory himself uses a very similar tactic in his Funeral Oration on Meletius: imagining Meletius’ earlier installation as bishop as a wedding to his bride, the Church at Antioch, Gregory then describes Meletius’ funeral as a reversal of those earlier celebrations: ‘Then we rejoiced with the song of marriage, now we give way to piteous lamentation for the 21 III.5, NPNF V, p.346 (GNO VIII/1:261:6-7). 22 See Himerius Or. 9:18, tr. Penella p.153. 23 III.7, NPNF V, p.347 (GNO VIII/1:263:9-10). 24 See for example, the evidence of Greek epigrams and epitaphs presented in Richard Seaford, ‘The Tragic Wedding’ in The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 107 (1987), pp.106, n.11; p.107, n.16-21; p.110, n.40; p.112, n.64; p.113, n.81, 83 and in H. Gregory Snyder, A Second-Century Christian Inscription from the Via Latina, Journal of Early Christian Studies, 19:2 (2011), pp. 157-195, especially p.168: ‘Imagery connected with rituals of marriage and rituals of death overlap to a surprising extent in funeral poetry’. 10 sorrow that has befallen us! Then we chanted an epithalamium, but now a funeral dirge!’25 But just because this technique could be used in funereal contexts does not mean that it was only used in such contexts. Rather, I argue that the reversal of the epithalamium is a technique that could be used for different literary ends – not that Gregory is simply borrowing tropes straight from funeral speeches. When a writer uses a technique like this the first question one should ask is: to what end? But Gregory also ‘goes beyond’ simply reversing the ekphrasis of the bride in another sense. He does not merely create a series of antitheses which juxtapose life with death, but he also self-consciously creates his own poetic voice. Just as Himerius fictionally ‘stands next to the bedroom’,26 describing the bride and praying for children, so Gregory positions himself in the same place, but as a first-hand witness of misery. He uses the language of tragedy as a literary device to emphasis his authorial role as both spectator and describer. This stance explains the extraordinary vividness of his portrait of a marriage. Without understanding the context, one might well feel that his description is over the top – just as an outraged aunt might misinterpret Himerius’ vivid description of her niece’s beauty, if she did not realise that the description was based on a poetic fiction. The whole point of Himerius’ ekphrasis of the bride is that not only can the audience not see the bride, but neither can he: ekphrasis is the description of something absent. This would have been understood by an ancient audience. Gregory, I believe, takes this literary conceit behind ekphrasis even further to 25 Gregory of Nyssa, Funeral Oration on Meletius (tr. William Moore, NPNF series 2, vol. V, p.513). See also p.514. 26 See Himerius Or. 9:21, tr. Penella, p.155. 11 heighten its effect. He does not describe the bride directly, but describes the husband seeing his bride. Furthermore, the theological point of Gregory’s ekphrasis is that what the groom sees – her eyes, eyebrows, cheeks, lips, hair – is merely ephemeral – ‘all that transient grace’. So when the groom looks at his bride’s beautiful flesh, in fact what he sees, according to Gregory, is her ‘noisome and unsightly bones’. Throughout, then, Gregory questions what is really there: the groom sees a corpse which is not yet present, but there is a sense in which the ‘beauty [which] will melt away and become as nothing’ is not really there either, precisely because of its ephemerality.27 In the rest of the treatise Gregory asks his audience to reflect on a true and lasting kind of beauty, ‘a beauty which is in itself beyond speech’, unlike the beauty of the bride which he is so consummately able to describe.28 In sum (and in answer to my earlier question – to what end?), Gregory uses the rhetorical technique of ekphrasis, not in a mechanical, but in a highly sophisticated and theological way which relies on the audience’s understanding that it is a description of something which is not really present.29 In the following two sections I will examine two more examples of the way in which Gregory uses poetic devices to make a theological point. 2. The chorus and chorus-leader (χορός, χορηγός) 27 NPNF V, p.346 (GNO VIII/1:259:21-5). 28 Quotation from Michel René Barnes, ‘ “The Burden of Marriage” and other notes on Gregory of Nyssa’s On Virginity’ in M. F. Wiles and E. J. Yarnold, with P.M. Parvis (edd.), Studia Patristica Vol. XXXVII, (Leuven: Peeters, 2001), p.12-13. 29 On this use of ekphrasis more generally, see Webb, Ekphrasis, chapter 4. 12 As I suggested earlier, Gregory uses a wider range of imagery from wedding literature. Here I will focus on one particular motif: that of the chorus. Greek and Roman weddings involved the singing of marriage-hymns. Lyric poets, such as Sappho, Theocritus and Catullus present their some of their epithalamia as hymns, sometimes (as in the case of Catullus Poem 62) a hymn sung antiphonally between a choir of girls and a choir of boys. Sometimes the antiphon has a mythical setting (as in Theocritus Poem 18’s hymn to Helen and Menelaus); sometimes the antiphon becomes less hymn-like and more agonistic (thus, the two choirs of girls and boys in Catullus 62 in effect debate the question of marriage). Sappho fragment 131 adapts the antiphon form to individual speakers: a bride addresses parthenia, Virginity.30 It seems likely that this agonistic-antiphonal tradition of epithalamic poetry lies behind Gregory of Nazianzus’ antiphonal debate poem on virginity.31 These poetic debates about the good of marriage also influenced the prose discussions of the good of marriage in rhetorical epithalamia (indeed, it seems likely that across the centuries there was mutual influence between poetry and prose). Another aspect of the hymn-like epithalamic poetry is that the poet presents him or herself as the chorus-leader or choregos, urging the others to sing, invoking the god and 30 Arthur Leslie Wheeler, ‘Tradition in the Epithalamium’ The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 51, No. 3 (1930), pp. 218. 31 Gregory of Nazianzus, Poem 1.2.1 In laudem virginitatis, PG 37:521-78, tr. Peter Gilbert, On God and Man, The Theological Poetry of St Gregory of Nazianzus (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2001), pp.88-118. 13 encouraging the bride and groom.32 Thus the poet participates in the ceremony not just as a close observer, as we have seen already, but as a leader whose role is to exhort. This role in turn is not so far from the typical role of the rhetor, so it is natural to find Menander describing the purpose of the ‘bedroom speech’ (a specific kind of epithalamium) as ‘an exhortation to intercourse’ (προτροπὴ πρὸς τὴν συμπλοκήν) and advising his pupil to encourage the rest of the wedding-guests to ‘put on garlands of roses and violets’, ‘light torches’ and ‘start a dance’.33 Himerius’ Epithalamium (Or. 9) closes on a very similar note. Clearly, Gregory’s De virginitate contains rather a different kind of exhortation,34 but it does also contain references to choruses. In chapter II, Gregory points out that virginity has a cosmic, supramundane origin (just as pagan authors claimed for marriage, as we shall see 32 See especially Catullus Poem 61 and Sappho frags. 128-130. Wheeler, ‘Tradition in the Epithalamium’, p.217: ‘In the sixty-first poem the most interesting feature of the technique is the mimetic-dramatic character - the manner in which the poet takes part in the ceremony assuming the role of a master of ceremonies or chorus leader’. 33 Menander Rhetor, Treatise II.vii The Bedroom Speech, trr. Russell and Wilson p.147. Gregory of Nyssa De virginitate VII.1 [or VIII.1] NPNF V, p.352: ‘it is a superfluous task to compose formally an Exhortation to marriage (προτροπὴν ὑπὲρ γάμου). We put forward the pleasure of it instead, as a most doughty champion on its behalf’ (GNO VIII/1:282:9-12). 34 See the title of Gregory of Nyssa De virginitate Preface ‘A letter giving the details which constitute an exhortation to a life of virtue (προτροπὴ εἰς τὸν κατ’ ἀρετὴν βίον)’, (tr. Callahan, p.6). 14 below).35 The Father begot the Son in a pure way without passion, therefore, Gregory asserts, the Son is the ‘chorus-leader (χορηγῷ) of incorruptibility’.36 Towards the close of the same chapter, the quality of virginity is personified and identified with Christ himself who, although he no longer appears to humans in bodily form, has such power that ‘he remains in the heavens with the father of the spirits, and dances in the chorus (χορεύειν) of the supramundane powers, and reaches out to human salvation’.37 By contrast, in chapter III it is marriage, not virginity, which is the χορηγός – the Greek word here being used to mean not chorus leader, but the one who provided, that is paid for, the chorus in a drama. Building on his use of tragic language, Gregory writes that marriage, through the procreation of new humans, is the one who provides the chorus for the tragedy being played out on the stage of life.38 Finally, towards the end of the treatise Gregory provides two examples of those who have not only led a virgin life, but who encourage others in it: first, Miriam, the ‘prophetess’ who led a ‘chorus of women’ (τοῦ χοροῦ τῶν γυναικῶν) or a ‘chorus of virgins’ (τοῦ χοροῦ τῶν παρθένων) and secondly an unnamed ascetic leader, presumably Basil, who is described 35 On the significance of this: Aubineau, Grégoire de Nysse. Traité de la Virginité, p.151-2. 36 De virg. II.1 (GNO VIII/1, 253:13). Translations from Nyssen are my own unless otherwise indicated. 37 II.3 (GNO VIII/1, 255:5-7). 38 De virg. III.10: ‘The provision (ἡ χορηγία) of the chorus of evils which come from marriage is manifold and varied’ (GNO VIII/1:265:14-15) and ‘But leaving all these things aside, look on the tragedies being enacted on the stage of this life, tragedies for which human marriage is the provider of the chorus (χορηγὸς)’, (GNO VIII/1:266:9-11). 15 as being in charge of a chorus of ascetics (χορὸν ἁγίων).39 Through the repetition of the choric language Gregory is surely suggesting that Miriam’s and Basil’s bands are imitating in their dancing the heavenly dance above. Now it is true that by the fourth century the Greek word chorus could be used simply to signify a group of people – for example a group of pupils or ascetics.40 But I think that the origins of the word are not lost and that in Gregory’s text it is not a totally dead metaphor. We have seen that the notion of dancing remained in the image of Christ leading a dance of the heavenly spirits and Miriam leading her band of virgins – images which to cultivated Greek readers would surely echo mythic concepts – for example, the idea of Apollo leading a heavenly chorus of the Muses. Himerius, for example, writes of Apollo as ‘the leader of the Muses [who] organizes choruses of the Muses (χοροὺς Μουσῶν) on Mt. Helicon’. Furthermore, Himerius uses the idea of earthly imitation of the choruses, for he flatteringly 39 Miriam XIX.1 NPNF V, p. 364-5 (GNO VIII/1, 322:26, 323:13); Basil: XXIII.6, NPNF V, p.370 (GNO VIII/1, 340:4-6). 40 The word chorοs (χορός) was used in classical and late antiquity for a group of pupils (see e.g. Themistius, Or. 24, in Robert J. Penella, The Private Orations of Themistius (University of California Press, Berkeley, 2000) ). Sometimes the underlying musical/dramatic metaphor was not hidden: see Himerius Or. 66, (tr. Penella, pp.94-6), in which Himerius compares his out-of-control students to a misbehaved chorus of Apollo; cf. Himerius Or. 21 (tr. Penella, p.123-4; see Penella’s introduction, ibid. p.73). 16 suggests that his addressee has ‘made Attica a workshop of the Muses’ activity, just as Apollo has done to Helicon’.41 In De virginitate Gregory plays with these two different resonances in Greek culture (the chorus in tragedy and a chorus of virgins/Muses) to highlight a difference between virginity and marriage. On the one hand, marriage is personified as the provider of the chorus in a tragedy; on the other, virginity (or Christ, or Miriam or Basil) is portrayed as the chorusleader of a group of virgins, similar to the Muses or to young maidens at a weddingcelebration. But Gregory also seems to play with the notion of himself the author as chorusleader. As we have seen, in this persona the poet or rhetor is deeply involved in the dramatic action: he encourages the bride and groom, but – obviously – he is not the one getting married. This seems strikingly parallel to the situation of De virginitate in which Gregory admits that he is praising virginity and encouraging others to it, whilst not being able to enter into the condition himself. He even seems to allude to the poetic stance as observer: ‘We are but spectators (θεαταὶ) of others’ blessings and witnesses (μάρτυρες) to the happiness of another class’.42 To some extent Gregory is using the standard rhetorical trope of asserting his inadequacy to describe what he is about to describe, but he is also perhaps hinting at an explanation which would best make sense of his rather awkward position in advocating a life he could not possibly lead: there are cultural contexts in which one person exhorts others to a course which he himself cannot pursue. 41 Himerius, Or. 47:9, tr. Penella, p.256. See also Himerius Or. 22, tr. Penella, p.80 (‘the Muses dance together on Mt. Helicon’) and Or. 48:2 and 6, tr. Penella, p.259, p.260. 42 De virg. III.1 (GNO VIII/1:256:17-19). 17 But, there is, I think, another reason for Gregory’s use of the chorus motif. Gregory does not actually assert that sex and marriage are bad things in themselves. He does say, however, that they are transient and their consequences are transient. Furthermore, as others have remarked, Gregory’s analysis of marriage is that it is a social, rather than a sexual, phenomenon: its goods and drawbacks are analysed in terms of the personal relationships it creates and the social responsibilities it imposes.43 This is a thoroughly Roman conception of marriage. Many epithalamia, in their assessment of the goods of marriage, comment on the fact that it is good not just for the cosmos, but good for society, good for the family, good for the state.44 One natural conclusion then, is that in rejecting marriage, or at least in advocating celibacy, Gregory is advocating a route which is profoundly ‘asocial’ (Brown) or ‘anti-social’ (Pagels) – a withdrawal from society.45 This interpretation can be understood in two ways. Brown’s point is often that Christian asceticism challenged Roman society by the establishing of strange new communities, of alternative households.46 Here the emphasis is on the exchange of one community for another with completely different values. On the other hand, 43 For a survey of commentators who have stressed this reading of De virginitate, see Ludlow, Gregory of Nyssa, Ancient and (Post)modern, pp186-201. 44 See Himerius’ Or. 9 and Menander Treatise II.vi. 45 Peter Brown, ‘The notion of virginity in the early church’, in B. McGinn et al. (eds.), Christian Spirituality, i: Origins to the Twelfth Century (Routledge, London, 1985), p.435; Elaine Pagels, Adam, Eve, and the Serpent (Random House, New York, 1988), p.83–4. 46 Peter Brown, The Body and Society: Men, Women and Sexual Renunciation in Early Christianity (Columbia University Press, New York, 1988), p.289-91. 18 Brown’s emphasis in The Body and Society on the importance of the individual body as the focus of much ascetic effort and his concentration on certain key ascetics (such as Macrina) as exemplifying the Christian ascetic enterprise does lead to an individualistic trajectory in much of his argument. Similarly, in much feminist interpretation of early Christian asceticism there is a strong contrast drawn between the commonality of Roman society and the individuality of Christian asceticism. For example, Pagels argues that in De virginitate Gregory ‘writes longingly of the freedom to be antisocial, to choose, as more valuable than anything else, his own, single life before God’.47 This analysis elides with a common construal of the late antique Christian ascetic as an individual bound in his or her own personal trajectory towards God. Undoubtedly, the kind of language Gregory uses for the ascent of the soul to God in De virginitate X-XI and elsewhere in his works contributes to interpretations which focus on individual interiority. Consequently, it is tempting to read Gregory’s reversal of the epithalamium genre as subverting and rejecting everything that marriage represents – including its social aspect. However, I do not think that this is the whole story. When a poet transfers a set of vocabulary or motifs from one context to another, something of the original context and thus of the original meaning remains. Thus, for example, Latin elegy used political language and the traditional imagery associated with marriage in poems dedicated to the relationships of lovers outside marriage. Such language was largely used ironically – but 47 Pagels, Adam, Eve, and the Serpent, p.83–4. My emphasis. 19 some of the original meanings remained, often to quite moving effect.48 Similarly, I suggest, when Gregory of Nyssa uses the language of marriage to praise virginity, he is not engaged in a purely witty exercise of reversal in which everything that marriage stands for is rejected. Rather, some of the marriage motifs are designed to show that there is a way in which the virgin life is like marriage and this, I would argue, is in virginity’s social aspect. That is, I would argue that Gregory is deliberately construing the vocation to a celibate life not as something which takes the ascetic out of his or her community to an isolated life before God, but rather as something which transforms the ascetic’s understanding of community. He or she may join a specific ascetic group, but the role of that group is still seen within the broader Christian church and indeed within human society more broadly. Contra Brown, Gregory seems to me to be suggesting not that Christian ascetic societies embody a whole new set of values, but that, paradoxically, they embody traditional values (such as harmony and fecundity) better than traditional societies do. Consequently, the language of the chorus in De virginitate reminds the reader that the life of a celibate was, at least in Basil’s monastic programme, a corporate exercise. Readers are advised ‘but if you cannot gaze upon him, as the weak-sighted cannot gaze upon the sun, at all events watch that band of holy men (χορὸν ἁγίων) who are ranged beneath him, and who by the illumination of their lives are a model for this age’.49 In De virginitate Gregory skilfully uses the language of chorus and chorus-leader to make the theological point that the 48 Hunter H. Gardner, ‘Ariadne's Lament: The Semiotic Impulse of Catullus 64’ in Transactions of the American Philological Association, 137:1, (2007), especially p.158. 49 De virg. XXIII.6 [or XXIV] (GNO VIII/1:340:2-6). 20 ascetic does not leave communal life (symbolised by the marriage-chorus) for a life of isolation; rather, his use of chorus language for ascetic life drives home the point that the ascetic exchanges one kind of community for another. In De virginitate, virginity is a new form of community, not an individual enterprise. The fact that Gregory’s praise of virginity praises it in social terms helps explain several puzzling features of the text. First, it explains Gregory’s advocacy of marriage halfway through. If one thinks of celibacy as an individual choice, then clearly it is a choice of one life-style over another. In terms of the Christian community in wider terms, however, one can think in terms of complementary vocations: some are called to the celibate life, others are married. Both are valued and a major concern of the treatise is that both life-styles are conducted in a godly way. Secondly, my interpretation helps us understand Gregory’s odd stance: a married man praising celibacy. Just as the unmarried rhetor or poet at a Roman wedding could without any contradiction praise marriage and even profess jealousy of the married couple so Gregory can praise virginity without contradiction. For marriage and virginity are being praised not only as good for the individuals who practise them but good for the community as a whole – indeed good for humankind as a whole. On this reading, to have a married man praising virginity is no more odd than someone in the congregation at an ordination service praising priesthood when he has no intention himself of becoming a priest. Therefore, attention to Gregory’s ‘poetic voice’ not only reveals a theological point that might otherwise be obscured (virginity is about new community), but it helps explain puzzling features of the structure of the treatise overall. 3. Water 21 Another dominant set of images from De virginitate are the various water metaphors. Their main message is clear: life, like water, needs to be controlled. On the one hand, the desires and distractions of life can be an uncontrollable and destructive torrent, carrying everything before them.50 On the other hand, a human mind that is allowed to run here, there and everywhere is like dissipated water whose flow is so slight and weak that it cannot be used for any good agricultural purpose.51 By contrast, the life of the person who is fully dedicated to God is described as a still pool, ‘smooth and motionless’52 or a ‘concentrated and collected’ stream.53 Given the treatise’s theme of spiritual fecundity, and the dangers of unrestrained desire, it is not difficult to see the connection here between water and fertility, and between water and desire. Virginia Burrus has commented perceptively on Gregory’s use of watery language both in this treatise and elsewhere. However, although her interpretation is nuanced, it does tend to associate Gregory’s water motifs primarily with human fertility: she traces the classical literary background of Gregory’s treatise back to Plato and argues that Gregory contrasts the physical sexual fertility of marriage with the ‘fertility of a virginal desire’ which is found in philosophy.54 Whilst agreeing with Burrus that this Platonic motif of ‘philosophic 50 De virg. IV.6, NPNF V, p.350 (GNO VIII/1:274:8 – 275:16). 51 De virg. VI.2 [or VII], NPNF V, p.352 (GNO VIII/1:280:9 - 281:25). 52 De virg. XV.2 [or XIV], NPNF V, p.361 (GNO VIII/1:310:19: λεῖόν ἐστι καὶ ἀκίνητον). 53 De virg. VI.2 [or VII], NPNF V, p.352 (GNO VIII/1: 280:18: ἀθρόῳ καὶ συντεταμένῳ). 54 Virginia Burrus, ‘Begotten, not made’ Conceiving Manhood in Late Antiquity (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2000), pp.84-97, especially p.90 and p.92. 22 maternity’ is present in De virginitate and acknowledging that sometimes Gregory does apply his water metaphors specifically to sexual desire,55 I would like to suggest that Gregory’s use of water images goes beyond this. For one thing, there are cases where Gregory seems specifically to be avoiding making a comparison between water and sexual desire. So, for example, before he uses the simile of the distracted life as a winter torrent, Gregory specifically lists the vices to which such a life is prone: avarice, envy, anger, hatred, the desire for empty glory, material wealth, human power, pride, a mad thirst for fame, love of honour, spite, empty conceit, honour, and pathological greed.56 Indeed, when Gregory specifies a ‘chain of vices’ in which one vice leads to another, lust is conspicuously absent.57 Furthermore, in the metaphor in De virginitate 6 which describes how water constrained in a 55 For example, later in his treatise he argues that just as an irrigation system guides an appropriate supply of water through proper channels to water crops, so sexual desire can be indulged sparingly and safely in marriage: De virg. VIII.1, NPNF V, p.353 (GNO VIII/1: 284:27 – 285:14); cf. De virg. IX.1, NPNF V, p.354 (GNO VIII/1: 287:4 – 16). 56 De virg. IV passim, NPNF V, pp.348-51 (GNO VIII/1, 267:13-14; 268:14; 268:21; 268:26 - 269:1; 269:5-6; 269:13-14; 269:18 269:21; 270:3; 272:23-5). 57 De virg. IV.5, NPNF V, p.350 (GNO VIII/1, 273:12-24): vanity, greed, anger, pride, envy, hypocrisy). The harmony of the still pool represents the unity of the virtues; just one vice can disturb its surface: De virg. XV.2 [or XIV] (GNO VIII/1, 310:18 – 311:8). 23 pipe can surge upwards against gravity, it is not desire, but the human mind (ὁ νοῦς ὁ ἀνθρώπινος) which is so constrained.58 The answer to the question of why water metaphors are so prominent in Gregory’s treatise can be found in two other places in Gregory’s classical Greek literary background. The first of these is once more the epithalamium genre. In their discussion of ‘the question of marriage’, classical authors not only gave examples of ideal human marriages (just as Gregory gives examples of ideal virgins, such as Elijah and John59), but also gave examples from mythology. Sometimes these recounted the ‘marriages’ of gods or heroes: the marriage of Peleus with the sea-nymph Thetis was one favourite example.60 Stories about the marriage of rivers or the gods associated with them seem to have been particularly popular: thus, for example, Menander Rhetor mentions the marriage of Alpheus to the Sicilian spring Arethusa 58 De virg. VI.2 [or VII], NPNF V, p.352 (GNO VIII/1, 280:19-20); cf. Gregory of Nyssa, Homilies on the Song of Songs IX (GNO VI:275:19 – 277:11) tr. Richard A. Norris Jr. (Atlanta: Society for Biblical Literature, 2012), p.291: the ‘the soul’s faculty of reasoning’ is constrained (GNO VI:275:20-1). 59 De virg. VI.1, NPNF V, p.351 (GNO VIII/1, 278:15 – 280:8). 60 See, e.g. Ps-Dionysius of Halicarnassus, 'Procedure for marriage speeches in D. A. Russell and N. G. Wilson (edd. and trr.) Menander Rhetor (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981), p.367; Menander Rhetor, Treatise II.vii The Bedroom Speech 409 in Russell and Wilson Menander Rhetor, p.153. See Seaford, ‘The Tragic Wedding’, pp. 106-130, especially p.109. 24 and the union of Poseidon to Tyro in the estuary of the Enipeus.61 Himerius recounts the latter story, artfully using it to echo an earlier reference to Poseidon: The Enipeus swelled in joy, surging and bulging up to form a bridal chamber, as if, I think , haughtily disposed toward other rivers because it alone had been entrusted with Poseidon’s love. [Poseidon] gathered a chorus of Nereids and raised up a bedroom for [Pelops] on a headland of the shore. The bedroom… was a wave, heaving and tall and curved up over the bed so as to resemble a bridal chamber.62 The popularity of such watery myths reflects another aspect of ‘the question of marriage’ in wedding-speeches. The orator was encouraged to go right back to explore the origins of the cosmos in terms of the marriage of various originating principles with each other: ‘Once born’, Menander writes, ‘Marriage unites Heaven with Earth and Cronos with Rhea…’. The god ‘even touches streams and rivers’.63 Himerius recounts that after God wed Nature64 there was a second marriage: ‘that of Ocean and Tethys, out of which emerged rivers and marshes, 61 Menander Rhetor, Treatise II.vi The Epithalamium 401-2 in Russell and Wilson Menander Rhetor, p.139. 62 Himerius, Or. 9.6, tr. Penella p.149 and p.147. 63 Menander Rhetor, Treatise II.vi The Epithalamium, 401 in Russell and Wilson Menander Rhetor, p.139. 64 Himerius Epithalamium for Severus 7, tr. Penella, p.148. 25 and also springs and streams and deep wells, and the sea, which is the mother of all waters’.65 Himerius illustrates this with the ‘marriage’ of ‘rivers to streams’, of ‘the Nile to Egypt’, and of the rivers Danube and Rhine to the Black Sea and the Atlantic, respectively.66 The appropriateness of watery motifs in Gregory of Nyssa’s De virginitate, then, seems to be due not only to the general connection of water with fertility, but more specifically to a habitual cultural connection made between marriage and myths about rivers. Certainly, we have evidence that such stories were expected of the orator attempting an epithalamium for Menander Rhetor advises, ‘You should incorporate narratives in all this: stories of rivers… and stories of creatures that swim…’.67 As if in obedience, Himerius gushes: Now if I should wish to speak of the loves of rivers, an endless throng of them would flow into my oration. For they all seem to me to love the ocean, and consequently they hasten on to it with great speed, each one wishing to greet its beloved before any other does. If we had to link the doings of rivers to marriage, then marriage would have been celebrated because of them.68 65 Himerius Or. 9.8, tr. Penella, p.148. 66 Himerius Or. 9.8, tr. Penella, p.148. 67 Menander Rhetor, Treatise II.vi The Epithalamium, trr. Russell and Wilson, p.139. 68 Himerius, Or. 9.11, tr. Penella, p.149. Later Himerius concludes, ‘So these (and all the rest) are the beauties of marriage; the poets sing of them, and it is customary to rehearse them at the bridal chamber’, tr. Penella, p.150. 26 It is tempting, then, to see Gregory’s own use of watery metaphors as a knowing gesture to another expectation of the epithalamium genre and as such it strengthens my argument that the whole of De virginitate (not just chapter III) is written with that genre in mind. But I would also argue that it is more than a witty reversal, more than simply an example of the ‘rococo tendencies of the Second Sophistic’.69 Rather, I suggest that Gregory is carefully manipulating this topos in two specific ways. Firstly, as we have just seen the whole point of the stories of rivers in epithalamia was to stress the cosmic importance of marriage: they are one important variation on the more general theme that love or sex or marriage is the grounding principle of the universe.70 The wedding we are here gathered today to celebrate, the rhetor is saying, is not merely important to Gladys and Gerald, nor even just to their family or their local community, but is just one example of a cosmic force which makes the world go round. In Gregory’s case, as we have already seen, he stands this trope on its head by arguing that it is not marriage but rather virginity which is a cosmic principle: at the beginning of his treatise he implies that virginity is a divine trait71 and then goes on to state quite directly, that, however paradoxical it might seem, it is virginity which lies at the apex of the cosmic order, for virginity is found in a divine Father who begat a Son, and is thus found in that Son too.72 Furthermore, Christ’s virginal human conception was the means by which 69 Michel René Barnes’ pithy summary of Aubineau’s assessment of De virginitate in Barnes, ‘ “The Burden of Marriage” ’ p.19. 70 Seaford, ‘The tragic wedding’, p.106. 71 De virg. I.1, NPNF V, p.344 (GNO VIII/1, 251:24 – 252:11). 72 De virg. II.1, NPNF V, p.344 (GNO VIII/1, 253:11-15). 27 God descended to share the human condition in the incarnation.73 So just as the cosmic principle of marriage is associated in rhetorical and poetic epithalamia with the mythical couplings of rivers, so in Gregory’s treatise the cosmic principle of virginity is expressed through the figures of the still smooth pool and the concentrated and collected stream. However, Gregory manipulates the traditional association of streams with marriage in a second way later in the treatise with his image of the carefully-planned irrigation system: here his argument is that sometimes a river needs to be diverted into a side-current in order to irrigate a field. This controlled use of water by the prudent farmer sounds much more like the usual stories of water in epithalamia and recalls the idea of the ‘marriage’ of (male) water to the (female) earth, which recurs in that genre.74 Consequently, the lasting impression that Gregory leaves the reader is that both virginity and marriage are necessary principles in the cosmos, albeit the former is associated with heaven and the latter with earth. I would argue that the way in which Gregory manipulates the topos of water intensifies the poetic mode of the treatise. We have seen already that the epithalamium theme called on the rhetor to use tropes and motifs which were also used in poetic epithalamia. But the poetic element extended from these specific ingredients to the more general question of 73 De virg. II.2, NPNF V, p.344 (GNO VIII/1, 254:17 – 255:14). Gregory of Nazianzus also uses this reversal technique in his poem On virginity, although he extends it by allowing ‘Marriage’ to claim her cosmic role first only to have it refuted by ‘Virginity’. Gregory of Nazianzus, Poem 1.2.1:412-41. 74 De virg. VIII.1 [or VII], NPNF V, pp.352 (GNO VIII/1: 284:27 – 285:14). See e.g. Himerius, Or. 9.8. 28 style: as Himerius puts it in the prologue to his Epithalamium for Severus, ‘the best rule for nuptial orations should be to look to the poets for diction (λέξιν)’.75 Accordingly, when he begins his oration proper, he compares himself to Apollo who ceased from serious poetry to ‘sing the wedding song over bridal chambers’; thus Himerius too is ‘summoning [his] Muses’.76 We have already seen that Menander recommends that one should ‘quote from Sappho’s love poems, from Homer, and from Hesiod…’.77 So we are to expect poetic diction and, as I have outlined, we have already found that in Gregory’s reversal of the ekphrasis of the bride, and his use of the poetic associations of the chorus motif. But there is something particularly poetic about using water as a motif and that it is not just that the myths of gods and rivers can be traced back to poets such as Homer. Rather, by Gregory’s day there was a long-established tradition of associating water with a poet’s reflections on his own art. In other words, water motifs do not merely signal poetic diction, but they signal a particular poetic self-consciousness. How is this so? First, particular bodies of water are associated with the great patrons of poetry: for example, Orpheus with the river Hebrus (on which his head and lyre continued to float and make music, even after his death) and Apollo with the Castalian spring at Delphi. From the 75 Himerius, Or. 9.1, tr. Penella, p.145. 76 Himerius, Or. 9.3, tr. Penella, p.146. 77 Menander Rhetor, Treatise II.vi The Epithalamium, trr. Russell and Wilson, p.141. 29 latter kind of reference it was a short step to use water as a symbol of poetic inspiration.78 However, different kinds of water became associated with particular literary styles. Perhaps most famously, Homer was associated with the Sea or Oceanos, because of his supreme command of epic.79 Other poets would compare themselves humbly with this model. For example, when Gregory of Nazianzus comments on his own use of the epic poetic metre he says that he is embarking on his sea-voyage ‘on a flimsy raft’.80 In other words, he may be using the same metre as Homer, but his own poem is a mere raft in comparison with Homer’s vast sea. The Alexandrian poet and critic Callimachus (third century BCE), imagines that his own poetry might be compared unfavourably to the sea (πόντος) – that is, Homer. He further imagines, however, that the god Apollo defends him: Callimachus’ poetry may be slight compared to that of Homer, but at least it is pure. In poetic language, Callimachus’ poetry is like a holy spring from which bees bring tiny drops of water to Apollo; it is not a large slowly-rolling river which gathers silt up in its muddied waters (i.e. a bad imitation of 78 See Plato, Phaedrus, 235d for an ironic variation on this idea. The dialogue takes place on the banks of the river Ilissus and it makes both repeated explicit references to water and implicit allusions to water as a symbol for poetic/verbal inspiration. 79 See Longinus, On Sublimity, 9.13, tr. D. A. Russell, in D. A. Russell and M. Winterbottom, Classical Literary Criticism (Oxford, Oxford University Press: 1972), p.153: in the Odyssey, the author claims, Homer is ‘on the ebb’. 80 Gregory of Nazianzus, Poemata Arcana (Poem 1.1.1; line 1) ed. C. Moreschini and tr. D. A. Sykes (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997), p.3. 30 Homer).81 Thereafter, watery symbolism came to be associated with poetic criticism: bad poetry would be condemned as a muddy stream,82 good with the grandeur of the sea,83 or a fine river.84 Himerius, the orator, uses water motifs to reflect on his own use of poetic diction in rhetoric, for example using the ‘ample and clear’ waters of the Ilissus (in Attica) to signal his use of Attic style85 or describing the poetry of Alcaeus in terms of the Castalian spring and the river Cephisus ‘swelling with its waves, in imitation of Homer’s Enipeus River’.86 In sum, then, water symbolism gave the ancient and late antique world a language with which to talk about poetry (and poetic style). It allowed writers to compare a literary style with that of one of the greats, or to compare two different kinds of good style, or to contrast good style with poor style. It allowed them to make claims about their own and others’ literary traditions and lines of inheritance. Finally, through the association of 81 Callimachus, Hymn II: Hymn to Apollo lines 105-113; tr. Frank Nisetich, The Poems of Callimachus (Oxford, Oxford University Press: 2001), p.27. 82 e.g. Horace, Satires, 1.4.10. 83 Longinus, On Sublimity, 12.3, tr. Russell, p.157. 84 See river metaphors for literary style in Longinus, On Sublimity 12.5 (‘deluged’), 32.1 (‘emotions come flooding in’), 32.4 (a ‘surging tide’ of metaphors), 33.4 (an ‘abundant, uncontrolled flood’), 35.3 (the grandeur of mighty rivers compared to small streams); tr. Russell, p.157, p.173, p.174, p.176, p.178. 85 Himerius, Or. 47.3, tr. Penella, p.254. 86 Himerius, Or.48.11, tr. Penella, p.262-3. 31 particular springs with gods like Apollo, it allowed writers to talk about their writing as an inspired and awe-inspiring activity. Where, then, does this leave us for Gregory of Nyssa and his treatise on virginity? Firstly, and more generally, the presence of so much water must surely alert us to the presence of a heightened and poetic discourse. If we haven’t noticed it already with the ekphrasis of the bride, the water metaphors must surely emphasise the point with vivid force: Gregory in this text is writing in a particularly poetic mode. Secondly, and more specifically, Gregory employs water symbolism to reflect on his own task. At the beginning, after he has signalled his intention to deliver an ‘encomium on virginity’ (τῶν ἐγκωμίων τῆς παρθενίας), he argues that to praise virginity is an impossible task, for it is above praise.87 To think one could appropriately praise virginity, indeed, would be to think that one could add significantly to the volume of the boundless sea (τῷ ἀπείρῳ πελάγει) with one drop of one’s sweat.88 This is not just a neat variation on the typical rhetorical excuse: ‘I am unworthy to write on this theme’. I contend, that this particular aqueous variation on the theme alerts the reader, at the very beginning of the text, that one should read the whole treatise in a literary – even poetic – mode. Should we therefore read his other watery metaphors in a similar vein? Could Gregory be signalling that his work is as much about his voice as a writer as it is about virginity – or marriage? Could it be that – in a variation on Plato’s Phaedrus – Gregory is using a speech which is ostensibly about love, also to say something about the place of rhetoric in his Christian community? 87 Gregory of Nyssa, De virg. I.1, NPNF V, p.344 (GNO VIII/1, 252:24-27). 88 Gregory of Nyssa, De virg. I.1, NPNF V, p.344 (GNO VIII/1, 253:1-3). 32 4. Conclusions I have chosen in this paper to focus on Gregory’s range of literary references to nonbiblical and non-Christian authors. This is, of course, not to say that biblical themes are unimportant. Indeed, much of his imagery could be further illuminated with reference to the Bible. For example, one could discuss stories about wedding-feasts – especially, perhaps, the parable of the ten maidens in Matthew 25, who could easily be construed as a kind of chorus.89 Equally, the Song of Songs must surely lie in the background of Gregory’s comments about a bride and a chorus of bridesmaids – especially in the light of Origen’s interpretation which repeatedly refers to the Song as a ‘drama’.90 Furthermore, passages such as Ecclesiasticus 24:29-31 illustrate the use of the metaphor of rivers and irrigation for spiritual fertility.91 Elsewhere I have argued that Gregory seems particularly fond of images that can be found in both biblical and classical texts and it seems likely that in De virginitate he is exploiting a range of symbolic and mythic language which is to a certain extent 89 We know that this passage was crucial to Syriac spirituality – especially ascetic spirituality (see e.g. Sebastian Brock, ‘Introduction’, to Ephrem, Hymns on Paradise, tr. and comm. Brock (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminar Press, 1990), p.27-29) ). 90 Origen, Commentary on the Song, e.g. Prologue, 1 and 2; I.2. See also Joseph R. Jones, ‘The "Song of Songs" as a Drama in the Commentators from Origen to the Twelfth Century’ in Comparative Drama, Vol. 17, No. 1 (Spring 1983), pp. 17-39. 91 Ecclesiasticus 24: 29-31. 33 common to biblical and classical literary traditions.92 In this paper, however, I chosen to concentrate on classical literary connections, in order to get a clearer focus on the question of artful composition. It is relatively easy to view biblical references as having an underlying theological meaning; my aim here has been to argue that there is also a theological purpose to Gregory’s use of classical literary sources and motifs. In other words, to put it crudely, we are not to assume that biblical water imagery, for example, is symbolic theology, but that classical water imagery is mere decoration. In this paper, then, I have supported Michel Aubineau’s contention that Gregory’s writing is clearly highly artful, although (unlike Aubineau) I do not completely discount the possibility that Gregory is writing from personal experience nor that Gregory’s writing is still capable of eliciting a sympathetic emotional response from his readers. Secondly, and more importantly, I have shown that Gregory’s range of reference goes well beyond the worlds of philosophy and rhetoric (at least, rhetoric as often and narrowly conceived): his ekphrasis of the bride and some of the water symbolism borrow from the lyric epithalamic tradition; other water images echo epic; the juxtaposition of thanatos and thalamos is a theme found in Greek funerary epigrams;93 Gregory systematically uses the language of tragedy not only to describe the impact of death on the married couple but also to play with the notion of the chorus and 92 Morwenna Ludlow, ‘Divine infinity and eschatology: the limits and dynamics of human knowledge according to Gregory of Nyssa: Contra Eunomium II §§67 – 170’ in Gregory of Nyssa: Contra Eunomium II ed. Lenka Karfíková et al. (Brill, Leiden, 2007). 93 See above, footnote 24. 34 chorus-leader.94 I am not necessarily arguing that Gregory is going beyond what would be expected of a good rhetor; but I am stressing that a good rhetor had a very wide range of literary reference in both prose and poetry. This is especially evident in epideictic rhetoric (the rhetoric of praise and blame), which lacked the more obviously functional context of the law-court or political audience. ‘In epideictic… the poet and the orator are much more on a level: both may be summoned to commemorate an occasion, both hope to leave behind them something which will endure’.95 Indeed, the speeches of the rhetor Himerius, who frequently compared himself to the lyric poets, demonstrate that a rhetorician was capable of creating a highly self-conscious and self-consciously poetic literary voice.96 Thirdly, I have argued here that in Gregory’s case this poetic literary voice was used to make properly theological points. I have suggested that Gregory uses the ekphrasis of the bride to emphasise the transience of human life, that he uses chorus motifs to stress that virginity is a social and corporate enterprise and that he uses water motifs to signal not only the fertility of Christian wisdom, but also a particular poetic sensibility through which he reflects on his role as a Christian rhetorician. 94 For references see Aubineau, Grégoire de Nysse Traité de la Virginité, p.94. 95 Russell and Wilson, Menander Rhetor, a Commentary, p.xxxii. 96 See Penella, The Man and the Word, p.14-16: Himerius compares himself not only to Homer, but to lyric poets such as Pindar and Simonides; he quotes from Alcaeus, Alcman, Anacreon, Bacchylides, Ibycus, Pindar, Sappho, Stesochorus. Penella comments: ‘Himerius is proud of his profession, proud of the traditions of logoi. Yet the vatic and aesthetic possibilities of poetry fascinate him.’ (at p.16). 35 In sum, I am not only challenging Michel Aubineau’s rather negative assessment of the success of Gregory’s technique. I am also challenging his method of commentary on Gregory’s De virginitate, which tends to identify a rhetorical trope without explaining how it functions in Gregory’s treatise. One problem with this method, as Michel Barnes points out, is that Aubineau ‘has argued that some sections of On Virginity are so purely reflective of the sophistic rhetoric of this era that they are functionally empty of content’.97 Barnes himself supplies this content by referring some of the material on the pains of marriage to Stoic precedents. Whilst accepting Barnes’ argument that the philosophical background of Gregory’s writing is important, I think one needs to go further. For both Aubineau and Barnes seem to assume that neither a rhetorical trope nor a literary device can bear theological content: in order to ‘redeem’ chapter III of De virginitate, Barnes feels compelled to find philosophical, not a literary, precedents. This is despite the fact that Barnes makes very perceptive remarks about Gregory’s use of tragic language and fact that he recognises that a dominant question in the treatise is precisely whether language – especially rhetorical language – is adequate to describe the divine beauty it is attempting to describe:98 Gregory makes much of the reaction that virginity provokes: he introduces the book as speech about a beauty which is in itself beyond speech. The deep suspicion of rhetoric and its inherent moral ambivalence that Gregory learned from Macrina reveals itself almost immediately, although this suspicion does not stop Gregory from indulging in rhetorical flourishes: hardly anything is so 97 Barnes, ‘ “The Burden of Marriage” ’, p.13. 98 On tragedy: Barnes, ‘ “The Burden of Marriage” ’, p.17; quotation p.12-13. 36 stylized as Gregory's renunciation of style. The fact that Gregory brought into his text an explicit evaluation of rhetoric and the propriety of speech for the subject of virginity has proven somewhat ironic, or at least far-sighted. Whilst the first and final sentences of this extract are extremely insightful, the whole betrays an extremely interesting attitude to rhetoric itself. Barnes seems to imply that De virginitate is not itself a piece of rhetoric – at least not in toto. Rather, it is written in another mode/using another discipline (philosophy, perhaps?) which at times uses extended rhetoric tropes (the pains of marriage), at other times indulges in ‘rhetorical flourishes’ and elsewhere puts rhetoric under the lens as the object of analysis. Rhetoric seems to be considered a matter of style, not argument (‘this… does not stop Gregory from indulging in rhetorical flourishes: hardly anything is so stylized as Gregory's renunciation of style’). But is it not artificial to separate rhetoric from philosophical theology in this way? Why not regard the whole of De virginitate as an exercise in theological rhetoric, as Gregory invites us to in the Prologue? Do Barnes’ comments in fact reveal that ‘the deep suspicion of rhetoric and its inherent moral ambivalence’ is in fact his own and not Gregory’s? Nevertheless other recent developments in scholarship challenge us to read Christian writing in late antiquity as taking place in a world in which there were not considered to be rigid oppositions between poetry and prose;99 between ‘useful’ (i.e. argument-based) and 99 Webb, Ekphrasis, Imagination and Persuasion, chapter 4. 37 decorative (i.e. rhetorical) prose,100 and between theology/philosophy and rhetoric. 101 The work of classical scholars such as Donald Russell, Malcolm Heath, Robert Penella and Ruth Webb suggests a much richer, less rigid and more lively rhetorical tradition in late antiquity than was once thought. The reading I have suggested is in broad continuity with this scholarship; it also draws on several recent scholarly debates about Gregory of Nyssa in particular, but presses them somewhat further. Thus, whilst appreciating more literary 100 e.g. Heath, Menander, p.xiii-xvii, p.284-94; Matthieu Cassin, L'écriture de la controverse chez Grégoire de Nysse : polémique littéraire et exégèse dans le Contre Eunome, (Paris : Institut d'É tudes Augustiniennes; Turnhout : Brepols, 2012), especially the reference to ‘un art d’écrire chrétien’ on p.370. 101 See Penella, The Private Orations of Themistius, especially p.4-5, p.14-16, pp.18-24, pp.28-31, pp.40-43 (on Themistius, Orr. 21, 23, 24, 26, 28, 29, 32). See also Heath, Menander, p.74 and F.W. Norris’ commentary on Gregory’s Theological Orations, Faith gives fullness to reasoning : the five Theological orations of Gregory Nazianzen, (Leiden ; New York : E.J. Brill, 1991) on which Christopher A. Beeley comments: ‘Norris has convincingly shown that Gregory worked deliberately and by professional training as a “philosophical rhetor”…. That is to say, Gregory had a fundamentally integrative understanding of Christian theology, philosophy and rhetoric, which may surprise those who harbor the long-standing myth that philosophy and theology stand in opposition to rhetoric’ (‘Gregory of Nazianzus – past, present and future’, in ibid. (ed.), Re-reading Gregory of Nazianzus : essays on history, theology, and culture (Washington, D.C. : Catholic University of America Press, 2012). p.xi). 38 readings of De virginitate by scholars such as Mark D. Hart and Virginia Burrus, I have become convinced that a more minute (but, I hope, not obsessive) archaeology of Gregory’s literary sources is necessary to explain his theological argument. Hart and Burrus both read Gregory in ways which echo literary readings of Plato: their notions of irony and philosophic desire provide valuable lenses through which to read Gregory, but ultimately fail quite to capture the range of cultural reference in Gregory’s text – and thus I think fail to grasp some of its meaning.102 Similarly, while largely agreeing with Cassin’s notion of a ‘Christian art of writing’, I am questioning his assumption that the delicate intertwining of literary and theological elements means that the scholar must carefully examine Gregory’s sources in order to ‘clarify, for each element of his text, the respective parts played by theology and polemic’.103 My analysis of De virginitate suggests that the examination of Gregory’s sources is illuminating precisely because it suggests the fluidity between philosophical-theological and poetic modes of discourse: perhaps it would be impossible to disentangle them, even if one had full knowledge of the sources. In conclusion then, I contend that that De virginitate is not merely artful, but that it is a work of art.104 It challenges its modern readers to read the church fathers not only as 102 Burrus, ‘Begotten not made’; Mark D. Hart, ‘Reconciliation of body and soul: Gregory of Nyssa’s deeper theology of marriage’, in Theological Studies, 51 (1990); Mark D. Hart, ‘Gregory of Nyssa’s ironic praise of the celibate life’, Heythrop Journal, 33 (1992). 103 Cassin, L'écriture de la controverse, p.369. 104 This assertion merely opens the question of how one might assess the quality of this particular work of art. 39 rhetors, but to read them a little more like poets as well. This may mean adjusting our notion of art to fit Gregory’s own context,105 for Gregory’s text invites us to bring together our notions of what is useful (a concept which has dominated much discussion of ancient rhetorical argument) and what is beautiful (a concept which dominates discussions of rhetorical style and poetry). The text does this not just because of its range of poetic reference, but precisely because its author invites us to think of himself as the poetrhetorician, standing at the door of the celibate life, evoking the dance of both heavenly and earthly choruses and problematizing the status of his poetic prose through its implicit comparison with a watery stream. Read in this poetic light, figures about the proper channelling of water – which, read philosophically, denote the channelling of the human mind – perhaps also indicate Gregory’ concern about the correct channelling of his own literary art. Given that he cannot offer his own celibacy, is it his own artistic skill which he offers the church, as a means to lead the community on to beauty? In which case, De virginitate is his attempt to justify not just virginity, but also Christian rhetoric, as a common good for the new society of the church. 105 If our notion of art is appropriate to Gregory’s own context it should include not just the beautiful, but the useful. This is a sweeping contention, which is the subject of my forthcoming monograph, Theology, Art and Craft; however, for a summary justification of the claim with regard to Roman visual art, see Peter Stewart, The Social History of Roman Art (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008), especially p.2 and p.59. 40