Word - Skidmore College

advertisement

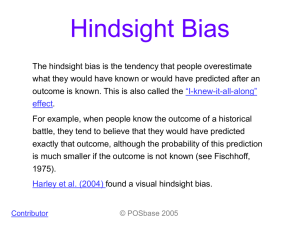

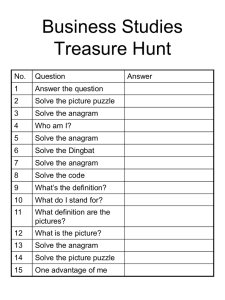

Running head: Effects of Task Difficulty on Hindsight Bias When the Shoe Won’t Fit: The Effects of Task Difficulty on Hindsight Bias 002390197 Skidmore College Effects of Task Difficulty on Hindsight Bias 2 Abstract We studied hindsight biases in the context of insight tasks, specifically anagram problems. We targeted the relationship between task difficulty and level of hindsight effects in order to understand why a positive correlation exists between these two variables. We tested each participant in both worksight and hindsight conditions, manipulating task difficulty level by using a variety of four-, six-, and eight-letter anagrams in each condition. Participants’ ratings indicated that their overestimations in the hindsight condition of the abilities of ignorant individuals to have solved the anagram increased with task difficulty, but that their underestimation of the anagram difficulties in the hindsight condition remained stagnant. By examining the interesting inconsistency of these results, we were able to more closely examine the validity of current hypotheses on the possible cause of hindsight, including the theory of mind, self-esteem protection, and memory error hypotheses. Effects of Task Difficulty on Hindsight Bias 3 Effects of Task Difficulty on Hindsight Bias Have you ever been told to “put yourself in someone else’s shoes”? Were you able to do it? This commonly used metaphor is another way of asking you to think how another person is experiencing a situation. It is a more practical way of asking you to put yourself in the mind of another person. Put this way, the task appears far more daunting. And, in fact, as extensive research on hindsight bias reveals, it is often more challenging then we think to place ourselves outside of our own minds and hypothesize about the experience of another’s. Hindsight bias is a psychological phenomenon in which an individual who knows the outcome of an event or the answer to a problem overestimates the ability of other individuals, as well as him or herself, to have foreseen the outcome or solution. Hindsight bias has been studied in a variety of contexts and with a variety of methods, including recollection of judgments before the occurrence or nonoccurrence of a significant event (Pease et al., 2003), the identification of objects in gradually clarifying photographs (Bernstein et al. 2004), and the solving of insight problems, such as anagrams (Hom and Ciaramitaro, 2001). All of these studies revealed that informed individuals tended to have difficulties putting themselves in the shoes of other hypothetical, uninformed individuals. Participants seemed unable to ignore their knowledge of an outcome or answer and consequently overestimated the abilities of an ignorant individual to have foreseen them. The evidence these and other studies have provided for the existence of hindsight bias directs our attention to the consequences of this bias in our society. Effects of Task Difficulty on Hindsight Bias 4 The most obvious consequence is that this tendency to overestimate the abilities of others when one already knows the answer can lead to unfair and ignorant expectations in educational institutions and work settings. In these situations, there is often a more knowledgeable professors or boss to whom the solution to a problem is obvious to. This may cause them to overestimate the abilities of their students or employees to find the same solution, resulting in unreasonable deadlines and minimal guidance. Hom and Ciaramitoro (2001), in their experiment on hindsight bias through the use of anagrams, indentified another consequence of the hindsight bias. They found, through comparing participants in both worksight (in which no anagram answer was provided) and hindsight (in which the anagram answer was provided) conditions that those effected by the hindsight bias were more confident in their future abilities to solve anagrams. This is another effect of hindsight bias that could help improve the performance of students and employees. If individuals had more confidence in their abilities when approaching challenging tasks, perhaps the experience would be less stressful and the quality of performance would be better. Considering these consequences of hindsight bias, we can see how valuable it would be to know how to manipulate this phenomenon. Hom and Ciaramitoro (2004) found that hindsight bias is indeed susceptible to manipulation. The five experiments within their study varied in elements such as time allocation and order of conditions, all of which resulted in different levels of hindsight consequences. Therefore we know that it is possible, through different methods, to manipulate the effects of hindsight bias. Effects of Task Difficulty on Hindsight Bias 5 But whether one wants to decrease or increase the effects of the hindsight bias, one first needs to understand what causes the hindsight bias and what aspects of it are subject to manipulation. Memory error, or the idea that an individual’s actual recollection of their own state of ignorance is tainted by the new information, is a widely agreed upon component of hindsight bias. The memory error hypothesis It is the bias recollection that leads to the inaccurate speculations of an ignorant individual’s abilities (Pease et al., 2003). Many studies have also hypothesized about other components of hindsight bias, though, finding that memory error did not always explain all of the effects of the phenomenon (Pease et al., 2003). Researchers have speculated about other motivational, developmental, and cognitive causes. Pease et al. (2003), in their study of the effects of hindsight bias on participants’ abilities to recall their own predictions of event outcomes, proposed the self-esteem protection hypothesis. This hypothesis suggests that individuals are motivated by a desire to appear less foolish or more knowledgeable, and will therefore report having predicted the outcome of the event when, in reality, they had not. Applied to other studies, this hypothesis could also explain why individuals, when given the answers to insight problems, tend to overestimate their own abilities to have solved the problem without the answers present. Bernstein et al. (2004) approached hindsight bias from a developmental stance, comparing the extent of hindsight effects on children and adults when identifying objects in gradually clarifying photographs on a computer screen. Participants were tested in both worksight and hindsight conditions, asked in the latter condition to speculate on when a same aged peer would have identified the Effects of Task Difficulty on Hindsight Bias 6 object. Their study revealed that when the same images were used in both conditions, hindsight bias declined with age. But when different images were used in each condition, hindsight bias was not significantly different between the age groups. From these findings they proposed that the development of theory of mind, or the ability to reason about another person’s thoughts or experience, is an important part of hindsight bias. Theory of mind develops in early adulthood, which could explain why the children, in one situation, had significantly greater hindsight biases than the adults. But the results also indicate that, in some situations, even an adult’s theory of mind may be limited, resulting in the same level of hindsight effect experienced by a child. Our study aims to explore these hypotheses and to further understand what contributes to hindsight bias. In doing so, we can figure out how to better manipulate and control this variable, and in which situations biases are more likely to occur. We chose to study the relationship between insight problem difficulty and resulting hindsight biases, another known method of hindsight manipulation (Hoch & Loewenstein, 1989). Hoch and Loewenstein (1989) found that hindsight consequences are positively correlated with the difficulty level of insight problems. By investigating this relationship more closely, we can explore what components of hindsight bias allow for this manipulation. In order to study the relationship, we designed the experiment to isolate the variable of insight difficulty by using anagrams. With anagrams, we could create clear levels of task difficulty by manipulating the letters of the anagrams. We designed a repeated measures experiment, in which each participant was tested in Effects of Task Difficulty on Hindsight Bias 7 both hindsight and worksight conditions. In the worksight condition, participants solved the anagrams themselves, without the presence of the anagram solution, and were asked to rate the difficulty of the problem. In the hindsight condition, participants saw the anagrams and the anagram solution and were again asked to rate the difficulty of the problem but were also asked to speculate on the abilities of an average person to solve the anagram. In both conditions, aside from the presence or absence of the anagram solution, we manipulated only anagram length. Based on previous literature, we predicted that longer anagrams (more difficult insight tasks), due to their higher complexity, would make participants more susceptible to memory error and pose greater limitations on their theory of mind abilities. Therefore, we predicted that as task difficulty increased, participant’s overestimation of another individual’s abilities and the underestimation of anagram difficulty in the hindsight condition would also increase. Method Participants This study was conducted by 41 Skidmore College students enrolled in an Experimental Psychology course. This experiment was a required assignment for said course. Each experimenter chose 2 participants with whom they would run the experiment. Thus, there were 82 participants, 33 were male, and 44 were female. 5 participants did not report their gender. The age of the participants was not recorded. Materials Effects of Task Difficulty on Hindsight Bias 8 The experimenters conducted the experiment on their two participants at different times over the course of a week. All experimenters conducted the lab in the same computer classroom, using the same software, set of instructions, and pre-set anagram program. The anagram program consisted of two different anagram designs, Anagram 1 and Anagram 2. Each design consisted of two, 15 word anagram sets. Each set consisted of and four-letter anagrams presented in a randomized order. For each anagram, the first letter of the anagram was also the first letter of the word solution. For example, “yolk” was represented in the four-letter anagram “ylok,” “weasel” was represented in the six-letter anagram “walseel,” and “hydrogen” was represented in the eight-letter anagram “hogdreny”. In Anagram 1, the first set of anagrams was used in the worksight condition while the second set was used in the hindsight condition. Anagram 2 used the sets of anagrams in the reverse order, using the second set of anagrams in the worksight condition and the first set of anagrams in the hindsight condition. Thus, the two designs consisted of identical sets of words, but differed in the conditions in which they used them. Procedure Each experimenter used both anagram designs, one on each of their two participants. The anagrams allowed for a repeated measure design, exposing each participant to both the worksight and hindsight conditions. The participants were read the instructions of the anagram task before beginning each condition. First, participants were tested in the worksight conditions. Anagrams appeared on the computer one at a time. Participants pressed Effects of Task Difficulty on Hindsight Bias 9 the space bar upon solving the anagram and then rated the difficulty of solving the anagram by entering a number from 1 to 5, 1 indicating the anagram was very difficult and 5 indicating that the anagram was very easy. The participants were not limited in the amount of time they had to solve the anagram, and were allowed to ask the experimenter for subsequent letters if they had difficulty solving the anagram. After the first set of 15 anagrams, the participants were then tested in the hindsight conditions. Anagrams appeared on the computer one at a time, this time with the solution to the anagram appearing above the anagram itself. The participants pressed the space bar when they thought a typical person would have solved the anagram. They then rated the difficulty of the anagram by again entering a number from 1 to 5 (1=very difficult, 5= very easy). After exposure to all 30 anagrams, the participants were debriefed on the purpose of the experiment. Ratings. Two composite variables were created and utilized after collecting the data from the experiment. These two variables are the dependent variables of our experiment and measure the extent of the hindsight effect on the participants. The number of letters in the anagrams (three levels: four, six, and eight) is the independent variable, which we will refer to as anagram length. Each anagram length corresponds with two variables, Difference in Response Times and Difference in Difficulty Rating between the worksight and hindsight conditions. Our ratings allow us to examine the relationship between the number of letters in the anagram and the extent of the hindsight effect. Effects of Task Difficulty on Hindsight Bias 10 The Differences in Response Times were computed by subtracting the mean response time, measured in milliseconds, of each anagram length in the worksight condition from the mean response time for each corresponding anagram length in the hindsight condition. Thus, if a participant had a mean response time of 6315 ms for the four-letter anagrams in the worksight condition and a mean response time estimate of 1620 ms for the four-letter anagrams in the hindsight condition, the participant’s Difference in Response Time for four letter anagrams would be 6316 – 1620, which yields 4694.8. The Differences in Difficulty Ratings were computed by subtracting the mean difficulty rating of each anagram length in the worksight condition from the mean difficulty rating of each corresponding anagram length in the hindsight condition. Thus, if a participant had a mean difficulty rating of 3.2 for the six-letter anagrams in the worksight condition and a mean difficulty rating of 3 for the six-letter anagrams in the hindsight condition, the participant’s Difference in Difficulty Rating for the six-letter anagrams would be 3.2 – 3, which yields .2. Both composite variables allowed us to determine by how much the participant over or under estimated another person’s abilities and the difficulty of the anagrams in the hindsight condition. Because the mean scores of the hindsight condition are being subtracted from the mean scores of the worksight condition, for both Differences in Response Times and Differences in Difficulty Ratings, a positive score indicates an underestimation of response time or anagram difficulty in the hindsight condition and a negative score would indicate an overestimation. Thus, Effects of Task Difficulty on Hindsight Bias 11 these two variables allow us to assess the effect of the three anagram lengths on the extent of the hindsight bias. Results Two, repeated measure one-way analyses of variances (ANOVA) were conducted to analyze the two composite variables separately. ANOVA revealed significant results for the Differences in Response Times across the three letter levels (F (2, 162) = 24.849, MSE = 1.248E8, p = .00, ² = .235). Post Hoc tests using Tukey’s HSD revealed, as shown in Table 1, that Differences in Response time for both six- (M = 12930.001) and eight-letter anagrams (M = 1197.870) were significantly greater than Differences in Response time for four-letter anagrams (M = 1520.484). Thus, hindsight bias effects were greater on participant’s judgments of other’s abilities to solve six- and eight-letter anagrams than on their judgments their abilities to solve four-letter anagrams. ANOVA revealed insignificant results for the Differences in Difficulty Ratings across the letter levels (F (2, 154) = .344, MSE = .465, p =. 160). Discussion The results both support and qualify our hypothesis that an increase in anagram length, which increases the difficulty of the task, would lead to increased hindsight effects. When looking at a six- or eight-letter anagrams, participants overestimated the ability of a typical person to solve the anagram by a significantly greater margin than when looking at four-letter anagrams. But participants underestimated the difficulty of the anagrams equally across all three anagram lengths. These results agree with Hoch and Loewenstein’s (1989) discovery that Effects of Task Difficulty on Hindsight Bias 12 with more complicated or difficult insight problems appear to have greater hindsight consequences, but only relative to the participant’s estimated response times. Anagram length, or task difficulty, had no effect on hindsight effects relative to the participant’s difficulty ratings. It is possible that the range of our difficulty rating scale, from 1 to 5, was not large enough to detect a significant difference in the participants’ ratings of the anagrams in the three different letter levels. It is also possible, though, that task difficulty only manipulates one aspect of hindsight effect. These results do not support, as Pease et al. (2003) suggested, that selfesteem protection could be this other component. If the self-esteem protection hypothesis were true then the participants in our experiment would have estimated the response time of a typical person to be longer than or equal to their own response time. On the contrary, our participants estimated the anagram solving ability of a typical person to be greater than their own ability. Therefore, hindsight bias, at least in regards to insight problems, is not a product of the individuals’ motivation to make him or herself appear less foolish or more intelligent. In fact, the more difficult the task, the more severely the individual tends to underestimate their own ability by overestimating the ability of others. These results suggests that either individuals are actually motivated by a cautious tendency to underestimate their own ability, or that conscious awareness of comparative ability and intelligence representation are not a factor in hindsight bias. Because the former suggests a complicated thought process that would have been unlikely to occur in the several seconds of response time, the latter hypothesis seems more likely. Effects of Task Difficulty on Hindsight Bias 13 Pease et al. (2003) made a valid point in saying that memory error does not completely explain hindsight bias, but our study reveals that conscious, motivated thought is most likely not the other explaining factor. The illogical, uncorrelated relationship between response time estimates and difficulty ratings suggests that hindsight bias is more likely the product of both memory error and the limitations of the theory of mind that Bernstein et al. (2004) discussed in their study. Both response time estimates and difficulty ratings were subject to memory error in this study because both tasks required the participant to reflect upon their own experience with the anagrams they had just completed in order to assess the new anagrams. But only response time estimates were subject to theory of mind limitations. The opinion of difficulty rating did not require our participants to reason about another person’s state of ignorance. Therefore, rating the difficulty on the anagram did not engage the participants’ theories of mind. Response time estimates, on the other hand, required the participants’ to put him or herself in the place of an individual that did not know the anagram solution, which did require theory of mind reasoning. Because the hindsight bias on the difficulty rating was unaffected by anagram length, we can hypothesize that memory error is a component of hindsight bias that is unaffected by task difficulty. Participants did err in their recall of how difficult the previous anagrams had been, which is apparent in their under and overestimations of the difficulty of subsequent anagrams, but this misjudgment did not vary significantly with anagram difficulty. The effects of hindsight bias on the response time estimates, though, actually increased with anagram length. This suggests that theory of mind is a component of hindsight bias Effects of Task Difficulty on Hindsight Bias 14 that is subject to greater limitations, and therefore greater hindsight effects, as task difficulty increases. Our participants’ difficulty ratings suggest that the participants recognized the increased difficulty of the longer anagrams, and yet their estimates do not reflect this recognition. Therefore it is in the theory of mind process, in the predictions of the abilities of another individual, that the error is being made. Participants knew the six- and eight-letter anagrams were more difficult than the four-letter anagrams, but were cognitively unable to translate this into their estimations of another person. As the task became more complicated, it is became more difficult for the individual to place him or herself in the shoes of an ignorant individual. The participants appeared to disregard the increased complexity, relative to the fourletter anagrams, of the six- and eight-letter anagrams when making their estimations. Theory of mind, it appears, is limited in its abilities to account for increased difficulty when making a judgment. Perhaps this is because individuals have a tendency to generalize an experience, and therefore make consistent estimations regardless of increased complexity. The illogical correlation could also be due to invalidity in the design of the experiment. For example, it is possible that theory of mind estimates simply do not translate well into behaviors. We asked the participants to essentially behave as an ignorant individual by actually pressing the space bar when they thought the ignorant individual would have solved the anagram. Perhaps if we had only asked the participants to write down the how long (in seconds) it would take a typical person to solve the anagram, the estimations would have been more accurate. The Effects of Task Difficulty on Hindsight Bias 15 results are also not very generalizable since the participants were most likely college students or professors. These types of participants may make the estimations of a “typical individual’s” abilities with other well-educated peers or coworkers in mind, which could result in the gross overestimation of that other person’s abilities. Also, to completely support our hypothesis, six-letter anagrams would have had to have lead to significantly greater overestimations in response times than did four-letter anagrams. This did not occur in our data, which may be because two letters did not produce enough difference in difficulty between the two anagrams to result in significant manipulation of theory of mind. Regardless of generalizability, though, the findings of this study reveal not just a component of hindsight bias, but also a component of hindsight bias that can be manipulated. The increasing error in estimations of the abilities of others as a result of increasing task difficulty implies that higher education may be subject to greater hindsight biases. Teachers of more complicated subject matter may be more likely to grossly overestimate the abilities of their students to solve problems or understand concepts in a certain amount of time. Teachers, especially at higher education levels, should be more aware of this and take it into account when designing tests and assigning due dates for crucial papers or projects. Further studies could examine this relationship of task difficulty and hindsight in the societal setting. Do professors at university tend to overestimate their students’ abilities more than high school teachers? More than elementary schoolteachers? Also, our study indicates only one method of manipulating hindsight bias. Are there methods that can manipulate memory error? Are there Effects of Task Difficulty on Hindsight Bias 16 other components of hindsight bias that can be manipulated? By understanding the contribution of theory of mind to hindsight bias, we can control future experiments to reveal these other possible components of hindsight bias. In doing so, we can continue to better understand this phenomenon, the methods we can use to control it, and the situations in which we are most vulnerable to it. References Effects of Task Difficulty on Hindsight Bias 17 Bernstein, D. M., Atance, C., Loftus, G. R., & Meltzoff, A. (2004). We saw it all along: Visual hindsight bias in children and adults. American Psychological Society, 15, 264-267 Hoch, S. J., & Loewenstein, G. F. (1989). Outcome feedback: hindsight and information. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 15, 605-619. Hom Jr., H. L., & Ciaramitaro, M. (2001). Gtidhnihs: I knew-it-all-along. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 15, 493-507 Pease, M. E, McCabe, A. E., Brannon, L. A., & Tagler, M. J. (2003). Memory distortions for pre-y2k expectancies: A demonstration of the hindsight bias. The Journal of Psychology, 137, 397-399. 18 Effects of Task Difficulty on Hindsight Bias Table 1 Mean Differences in Response Times and Difficulty Ratings Condition Measures Difference in (15292.7) Response Times Difference in Difficulty Ratings Four-Letter Six-Letter Eight-Letter 1520.484 (2376.8) 12930.001 (15569.5) 11197.869 -.087 (.52) -.019 (.69) -.001 (.88)