greta_lpfm_nyc

advertisement

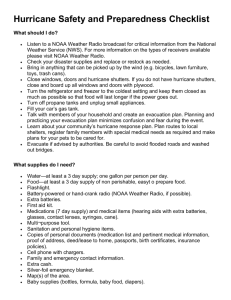

Greta Byrum December 17, 2010 Locating Low-Power FM Radio in NYC Strategic Risk Communication and Community Support for Vulnerable Populations The Planning Role of Community Radio Over the last three decades, small-scale community radio, once a staple of local news and information, has largely disappeared from the dial, especially in urban areas. Local broadcasting – of school board or community board meetings, about local candidates for office, etc. – has mostly moved to the Internet or disappeared. Some would argue that broadcast radio is an outdated medium. But many small groups of activists – and some larger, more influential actors and agencies – are advocating for small-scale radio broadcasting. They say that local noncommercial radio provides a unique service, and that the public interest would be served by policies designed to facilitate and protect it (Moyers, 2007; Prometheus, 2010; MAP, 2010). They are concerned about the media consolidation that has taken place since the passage of the 1996 Telecommunications Act, which removed barriers to media consolidation and presaged the buying-up of most of the country’s local non-profit stations, with some unfortunate consequences: “Minorities own only 7 percent of all local television and radio stations. Women own only 6 percent” (H.R. 1147, Local Community Radio Act of 2009). At issue is a class of broadcast licenses, allocated in very limited supply by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) since 2000. Low-power FM (LPFM) transmitters operate at 100 watts or less (about as much power as an incandescent light-bulb), which means they have a broadcast range of only up to three miles. Under current legislation, they are only permitted in rural areas. Yet many people argue that they may have a unique role to play in community cohesion and resilience, especially in disaster scenarios, and that licensing should be expanded. When Hurricane Katrina made landfall in New Orleans, 37 of the area’s 41 radio stations went off air. Of the remaining four, two were LPFM radio stations. One of these – WQRZ in Hancock County – stayed on-air 24 hours a day throughout the crisis and throughout the following months, broadcasting emergency information and community updates (Moyers, 2007). Small and mobile, and with minimal demands for power, it could adapt easily. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) doubled the station’s permitted broadcast range, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) started giving out radios along with water and ice. FEMA eventually requested station manager Brice Phillips to move his station to the Emergency Operations Center. This is just one case in which LPFM has proven adaptable to situations of scarcity and crisis. WQRZ was the only media organization in the area providing local information to residents throughout the Katrina crisis, mainly because of its stake in the community and its knowledge about local needs and conditions. Similarly, rural Florida’s Radio Conciencia, run by the Immokalee Workers’ Cooperative, also played an important role during Hurricane Wilma. As the only local station broadcasting in Spanish, it reached many people who otherwise wouldn’t have evacuated – a lot of those in particular danger because they were working in the fields or sleeping in trailers. People were also able to call into the station and get information and help evacuating. But even when there is not an emergency, Radio Conciencia is important for its community, broadcasting local news, culture, and politics both about Florida and about many of the workers’ home countries. Workers can listen to the radio in the fields and call in with song requests; the station is run cooperatively by community volunteers. The importance of radio in cases of disasters is clear, but I argue that this only telescopes a need that is already present in the community for locally owned and operated information networks. This study addresses two important planning areas served by LPFM broadcasting: 1. Disaster and risk mitigation and management 2. Community and capacity-building: Broadcasting local information and culture is important but so is the process of the community working together and learning the technology. The reason Radio Conciencia was able to save lives was because it already existed as a well-developed community asset beforehand. Rationale and Hypothesis Control of radio resources and spectrum occupies a pivotal position between use and occupation in a spatial sense, intellectual property rights, and freedom of expression. As such it presents unique challenges for regulation. I will show that control of the radio spectrum has consequences for planning, especially in times of scarcity and disaster. Allocation of portions of the radio spectrum to local non-profits would lead to greater community cohesion and communication, which in turn would lead to better risk management and everyday planning outcomes. Without policy provisions and spatial consideration for this allocation, control of the spectrum may be retained by commercially-driven, large-scale interests that do not have incentives to provide needed local information and connections. If the airwaves are viewed as a common-pool resource, then portions of the spectrum should be dedicated to LPFM broadcasting. This is a policy challenge since the spectrum is a valuable asset, continually being auctioned off for wireless and broadband. LPFMs have been the focus of intense debate, and although legislation has been introduced many times for the expansion of LPFM, and although the FCC has shown support for it, each time these bills have stalled in Congress. Since the Telecommunications Act of 1996, which resulted in massive media consolidation, institutions such as the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) and NPR have consistently fought against licensing LPFM stations on adjacent frequencies, citing concerns about broadcast interference. A 2003 study commissioned by the FCC, however, showed that the risk of interference is actually low to negligible (MITRE, 2003). Legislation currently in Congress will decide the future of LPFM by potentially opening the spectrum up to low-power operators in urban areas. If H.R. 1147, Local Community Radio Act of 2009, were to pass, it would open up LPFM licensing in New York City, an area that is currently dominated by large commercial broadcasters. Where could LPFM towers be placed in order to provide the best services to the community, especially in the case of emergencies or disasters? Literature Review The cases of WQRZ and Radio Conciencia represent the convergence of several planning issues, especially with relation to the emerging field of disaster planning. WQRZ clearly provided a valuable service to the community by issuing information that was unavailable through state agencies or national-media channels. This included vital information about evacuations and emergency resources, both of which are central to community preparedness and disaster planning (Kapucu, 2008). Hancock County, though it was located at the epicenter of the storm’s fury, clearly benefitted from having an established, resilient, adaptable local news source. New Orleans was not so lucky. Qualitative interviews conducted in 2005 among Katrina evacuees living in the Houston Astrodome revealed that the lack of local information compounded the effects of the disaster for many of those hardest-hit. Respondents indicated that their main source of information about the storm and the evacuation was television, but that “televised warnings about the hurricane but evacuation messages were recalled as nonspecific or ambiguous, for instance, messages to ‘go somewhere’ but not where and how to evacuate” (Eisenman et al, 2007). This is a crucial distinction in thinking about local information networks: these, presumably, could have offered more specific information or resources for ride-sharing, local emergency shelters, etc. In disaster literature, vulnerability is generally defined as “the characteristics of a person or group and their situation that influence their capacity to anticipate, cope with, resist and recover from the impact of a natural hazard -- an extreme natural event or process” (Wisner, 2004) Much post-Katrina literature analyzes the reasons why organizations failed to reach those marginalized by economic, political, social, or cultural circumstances (Philips and Morrow, 2006). The poorer citizens of New Orleans did not evacuate for a variety of reasons such as, for example, a lack of transportation. Those who were eventually forced to relocate now face other problems. A subset of disaster vulnerability research deals in particular with risk communications – that is, the extent to which people understand or heed warning messages. An example of vulnerability associated with warning messages in particular is the Saragosa, Texas, tornado of 1987, where two problems occurred. First, local media outlets attempting to warn those at risk mistranslated the word “warning” from English into Spanish. Second, a Spanish-language television station, originating outside of the local area but watched by locals, did not broadcast local warnings. Twenty-nine lives were lost. (Aguirre, 1988; Philips and Morrow, 2006) More literature regarding the variables that affect risk communication is in the “Findings” section below, in particular the factors of age, poverty, race or ethnicity, and linguistic isolation, all drawn from Philips and Morrow’s work on social science research needs for vulnerable populations. Methodology What is being targeted in this study is not the universe of vulnerable populations, but those which may not be reachable with existing media, or may not respond to warning messages. Further, many researchers believe that vulnerability factors tend to cluster, multiplying the risk spatially for certain segments of the population (Philips and Morrow; Wisner et al). Using a combination of demographic indicators for vulnerability, I have developed a methodology for weighting variables for communities that would most benefit from LPFM broadcasting. Then I created a vector decision map showing clustering of vulnerable populations, and indicating possible FM LPFM licensing locations. Steps: 1. Identify the variables that make populations vulnerable with regard to risk communication according to existing literature. 2. Based on the literature, choose the 4 most common dependent variables affecting vulnerability with regard to risk communication: poverty, age, race, and linguistic isolation. These were chosen because they cluster spatially and were commonly cited in multiple studies. Age -- Seniors do not access emergency services at the same rate as younger disaster victims. It is not clear exactly why, though it may be due to technological barriers. At least one study found that the elderly did evacuate at similar rates to others if they received the warning, though most have found that households with older members are reluctant to evacuate. Many researchers also believe that support networks are crucial in getting warnings to the elderly. (Philip and Morrow, 2006) The level of access to technology and the reliance on local support and social networks are reasons that the elderly are an important audience for LPFM. Race and Ethnicity -- Cultural groups, including racial and ethnic groups, “may be less likely to accept a warning message as credible without confirming it through other sources such as family and social networks, often delaying reaction” (Fothergill et al. 1999; Lindell and Perry 2004, as qtd in Philip and Morrow, 2006). This is due to distrust of those outside their immediate circles, including media and government figures. I have only used data on the African-American population here, partly because I thought that New York’s other largest ethnic populations (Latino and Asian) would be captured through the next variable, which is about linguistic isolation. Also, much of the literature examining the effects of Katrina, African Americans were identified as the racial group that was primarily affected. However a more comprehensive look at race might benefit the study. Poverty -- Poverty affects availability of resources/transport and ability to pay for lodging in motels, etc. Cities also have clusters of poverty, which creates difficulty for emergency services because of concentration of need. Linguistic Isolation – the US Census Bureau defines “a linguistically isolated household” as one “in which no one 14 years old and over speaks only English or speaks a non-English language and speaks English ‘very well.’” In other words, all members of the household 14 years old and over have at least some difficulty with English. Linguistic isolation is the variable most discussed in disaster planning for risk communication, since it has the most obvious effect on peoples’ ability to understand and respond to warning messages. In addition, linguistically isolated populations may not have an extended social network they can tap into for resources, lodging, and support in the case of evacuation. This is actually true of the other vulnerable populations as well. US Census Data at the block group level was used to show where these populations cluster in New York. 3. Create choropleth maps showing areas with densities of these populations in NYC. 4. Based on literature, create a rating system to weight the variables most important in affecting vulnerability. I weighted my chosen variables according to the literature. The two categories “very hard to reach” and “moderately hard to reach” are determined by looking at the standard deviation from the mean when all these weighted variables are combined. Weighting: Linguistic isolation: 40% Age: 25% Race (African American): 20% Poverty: 15% Since linguistic isolation is the clearest and most common determinant in the rate of comprehension and response to warnings, it got the highest weighting. Age and race were weighted similarly, since according to literature on Katrina they were the two most common variables. Age is weighted slightly higher because the link between technological access and risk communication (radio may be an easier media access tool for the elderly) was factored in, and also because several articles called for more attention to the problem of age in risk management. Poverty was weighted lowest because, although there seems to be a correlation between poverty and vulnerability in past disasters, this study is concentrating in particular on communication. The poverty issue creates difficulty more around the logistics of evacuation (transport, lodging) than receiving warning messages. 5. Creating a vector decision map identifying block groups that have the highest vulnerability index according to the above criteria. 6. Identify optimum LPFM placement in relation to these vulnerable block groups and other variables, for example proximity to OEM hurricane evacuation zones and centers. Using OEM data I was able to map hurricane evacuation zones in NYC as well as evacuation centers. Many of the block groups identified as being “very hard to reach” were located in evacuation zones, for instance in Harlem, Coney Island/Sheepshead Bay, Northern Queens, Greenpoint/Williamsburg, and Chinatown. These are areas that could were then targeted for LPFM licensing recommendations. 7. Create 2-mile buffers around possible LPFM sites at the block groups with the highest vulnerability indexes. Usually LPFM broadcast range is 3 miles, but in a dense city interference from buildings may block the signal. Create buffers also around the sites of the central hurricane centers, which are OEM distribution centers surrounded by smaller shelters whose locations are not disclosed. LPFM transmitters could be temporarily placed at hurricane shelters in the case of emergency. 8. Make recommendations for placement that could help the FCC decide where in NYC to approve licenses if Community Radio Act of 2009 passes. Limitations In terms of social science limitations, this study does not address many of the important factors that affect vulnerability in disasters, such as disabilities and gender. The reason for this is the focus on risk communications. Disabled populations and women do have particular difficulties with evacuating, as the disabled have trouble with mobility and transport, and women are often caretakers who must arrange logistics for others, such as children and the elderly. I did not focus on these variables the issues around their vulnerability are not primarily warning communications problems. Similarly, I did not address transport needs in disasters at all, since this study is about communication of risk and not what is communicated. In addition, I only looked at linguistic isolation, and not which languages in particular are spoken in NYC. This is because I was interested not in broadcast content (i.e. which language it is in) but in the presence of broadcasting. There are also technical limitations to this study. First, I did not perform ground elevation or building height analysis. Although these factors do affect broadcast range, LPFM broadcasting is so limited in scale that these factors are not as important as the others – LPFM will reach about 2 miles from any point if a transmitter is placed on a rooftop. Also, I am concentrating on FM and not AM broadcasting, as FM equipment is easier for communities to use and FM audio is not as compromised as AM by static and interference, especially in storms. Findings Based on this analysis, I have some recommendations for LPFM licensing in NYC if the FCC does allow for expansion into urban areas. I have identified the areas with the highest index of clustering of vulnerability factors, and mapped potential coverage if LPFM stations were placed in the 13 block groups with the highest rate of vulnerability. Most of the areas identified for clustering of vulnerability factors have multiple block groups that fit the criteria, so one or two LPFMs would probably suffice. Based on these criteria, I would recommend 5 or possibly 6 LPFM licenses in these areas. Ongoing presence of LPFMs in these areas would enable the second planning goal I identified as a possible benefit of LPFM – community development and empowerment. However, when you compare these broadcast ranges against the hurricane evacuation zones, there are still some high-risk flooding areas that wouldn’t receive broadcasting in the case of a disaster. However, hurricanes aren’t the only kinds of disasters. It’s just hard to predict where the others will happen. Another possibility would be to put temporary LPFMs at evacuation centers themselves. However, there is a lot of redundancy and overlap in this scenario – many of the centers are close together, so you wouldn’t need LPFMs at all of them. Also, the FCC would have to allot far more spectrum to LPFM for this many licenses. Based on this, my overall recommendation would be: six permanently available LPFM licenses for the 13 block groups identified as most vulnerable, with further frequencies reserved for LPFM use at evacuation centers in emergencies. Bibliography Mitre Technical Report: Experimental Measurements of the Third- Adjacent Channel Impacts of Low-Power FM Stations, Volume One: Final Report May 2003 Kapucu, Naim. “Collaborative emergency management: better community organising, better public preparedness and response.” Disasters, Volume 32, Issue 2, June 2008, Pages: 239– 262. Kim, Yong-Chan and Jinae Kang. “Communication, neighbourhood belonging and household hurricane preparedness.” Disasters, Volume 34, Issue 2, April 2010, Pages: 470–488 Coase, Ronald H. “The Federal Communications Commission.” Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 2. (Oct., 1959), pp. 1-40. Hazlett, Thomas, with David Porter and Vernon L. Smith. “Radio Spectrum And The Disruptive Clarity Of Ronald Coase.” Paper provided by Chapman University, Economic Science Institute in its series Working Papers with number 10-02. Media Access Project, “Low Power Radio.” Accessed November 18, 2010. http://www.mediaaccess.org/issues/lpfm/ Moss, David, and Michael Fein. “Radio Regulation Revisited: Coase, the FCC, and the Public Interest.” Journal of Policy History - Volume 15, Number 4, 2003, pp. 389-416 Bill Moyers Journal, “A Low Power Radio Katrina Story and Bill Moyers talks with Hannah Sassaman and Rick Karr.” PBS, August 24, 2007. <http://www.pbs.org/moyers/journal/08242007/watch2.html> Philips, Brenda D. and Better Hearn Morrow. “Social Science Research Needs: Focus on Vulnerable Populations, Forecasting, and Warning.” Natural Hazards Review, August 2007. Prometheus Radio Project. “Spotlighted! LPFM and the Local Community Radio Act. Accessed November 18, 2010. < http://prometheusradio.org/node/2367> Wisner, Ben et al. At Risk: Natural Hazards, Peoples’ Vulnerability, and Disasters. New York: Routledge, 2004.