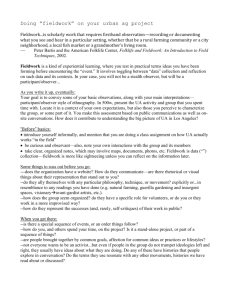

Doing Fieldwork

advertisement

Module 1, Lesson 2: What Is Fieldwork Really Like? Document #2: Doing Fieldwork Name______________________________ Date______________ Pd__________ The excerpt below comes from the book Doing Fieldwork: Warnings and Advice, by Rosalie H. Wax (1971). The author did fieldwork in the 1940s with Japanese Americans who were confined to relocation centers during World War II, and in the 1960s on several Native American reservations. In this excerpt, taken from the chapter “The First and Most Uncomfortable Stage of Fieldwork,” Dr. Wax explains some of the feelings and experiences of anthropologists’ first days in an unfamiliar culture. She discusses the kinds of learning and experience that have to occur before a fieldworker can begin to do their job. (Note that because this is an older text, the language will seem antiquated, such as the use of “he” to denote all fieldworkers). …Most field experiences that involve living with or close to the host people fall into three stages. First, there is the stage of initiation or resocialization, when the fieldworker tries to involve himself in the kinds of relationships which will enable him to do his fieldwork—the period during which he and his hosts work out or develop the kinds and varieties of roles which he and they will play. Second, there is the stage during which the fieldworker, having become involved in a variety of relationships, is able to concentrate on and do his fieldwork. Third, there is the post-field stage, when the fieldworker finishes his report and tries to get back in step with, or reattach himself to, his own people. …Usually a beginner arrives in the field ready and eager to begin “gathering data.” Then, for weeks, and sometimes for months, he gropes and wanders about, trying to involve himself in the various kinds of human or social relationships that he needs, not only in order to accomplish his work but because he is a human being. He tries to make the acquaintance of as many people as possible, and he tries to tell them who he is and what he hopes to do. He may also try to obtain permission to attend meetings or ceremonies, or he may tag along, as a quasi participant, with various groups. He may try to find a good language teacher, a competent interpreter, or, sometimes, a good clerical assistant. All this time, of course, he is trying hardest of all to find some person or persons who will advise, assist, and teach him, introduce him, or, as the Indians put it, “go around with him.” What happens to the fieldworker and his hosts during this involvement-seeking or roleconstructing period varies with each fieldworker and each situation. Nancy Lurie (1970), in her study of the Winnebago, seems to have had a remarkably agreeable first field experience, which she ascribes to the instruction and assistance given her by a wonderful old man. William F. Whyte also seems to have been relatively lucky. After several unsuccessful experiments such as knocking on doors and trying to discuss “living conditions” or approaching strangers in a bar and almost being thrown downstairs, he encountered Doc, the leader of a street corner gang. Whyte and Doc thereupon began a relationship which, whatever it meant to Doc, the sponsor-guide, was to be of enormous assistance to Whyte, the student-researcher. Powdermaker (1966) in her first field trip to Melanesia also seems to have made out very well, for she mentions only that for a few hours she felt frightened and isolated. But initiations so easy as these are, I suspect, rare. Carpenter (1965) tell us that when he began his work with the Eskimo, he felt for months like a mental defective. Gradually, however, his “feelings of stupidity and clumsiness diminished, not as a consequence of learning skills so much as becoming involved with a family, with individuals. If they hadn’t accepted me, I would have remained less than an outsider, less than human.” I had a similar experience on my first field trip to the Gila center, where it took me four months to develop any kind of social relationship, not because the Japanese Americans or I were socially maladept, but because almost everyone automatically defined me as “a spy for the administration.” Like Carpenter I often felt like a mental defective, and for about six weeks I felt as if I were losing my mind…Margaret Mead had even more difficulty among the Omaha: “This is a very discouraging job, ethnologically speaking. You find a man whose father or uncle had a vision. You go to see him four times, driving eight or ten miles with an interpreter. The first time he isn’t home, the second time he’s drunk, the next time his wife’s sick, and the fourth time, on the advice of the interpreter, you start the interview with a $5 bill, for which he offers thanks to Wakanda, prays Wakanda to give him a long life, and proceeds to lie steadily for four hours” (Mead 1966: 313-14). During this first stage of fieldwork, the fieldworker lives in a kind of social limbo, trying to behave as if he “belonged” and as if he knew what he was doing. He may give the superficial appearance of working very hard. He may approach many different people with his carefully composed description of who he is and what he is doing, carrying his list of carefully structured, “inoffensive” questions, and may wonder why they giggle, shake their heads, simply stare at him, or mumble, “I don’t know.” Or, like a young anthropologist friend of ours, he may energetically explore the paths of his new living quarters, only to find that most of them lead to his neighbors’ privies (outdoor bathrooms). Or, in his enthusiasm to participate in the lives of his hosts, he may settle down unwittingly, as Murray (the author’s husband) and I did, with a family notorious for its skill in relieving unsuspecting strangers of their money. He may, as we did, take extremely voluminous notes (sometimes because he has nothing else to do), and months later find that a good part of these early notes consist of amateurish observations that could have been made by any outsider—naïve hypotheses about the meaning of things various people did or said…or, when all else fails, long and detailed descriptions of the scenery…Painful and humiliating experiences are easier to talk about if one does not take them too seriously, and it is less distressing to picture oneself as a clown or figure of fun than as a dolt or a neurotic. The process by which a fieldworker moves out, and is moved out, of this uncomfortable and frustrating first stage is complicated, and it varies with each situation and each individual fieldworker. It may be as complicated and variable as the process by which an individual infant becomes a socialized and civilized member of his community. It resembles the latter process in that, among other things, it involves a great deal of learning or socialization (or, better, relearning and resocialization) on the part of the fieldworker (and sometimes of his hosts) and the mutual desire and ability to establish reciprocal relationships of the kind that will help the fieldworker learn what he wishes to learn and do what he wishes to do. Frequently it is during this period that the fieldworker also discovers that he cannot possibly do what he had hoped to do and, simultaneously, that there are many unsuspected avenues of investigation open to him. Usually the essential factor in this transformation is the assistance and support—the reciprocal social response—given him by some of his hosts. It is in their company that he begins to do the kind of “participation and observation” that enables him to “understand” what is going on about him at his own speed and at his own level of competence. It is his hosts who will let him know when he behaves stupidly or offensively, and will reassure him when he thinks he has made some gross blunder. It is they who will help him meet the people who can assist him in his work, and it is they who will tell him when his life is in danger and when it is not…He begins to learn how to accept obligations and how to repay them, when to ask questions and when to keep his mouth shut—in short, how to stay out of the most obvious kinds of trouble. Indeed, in the literal, ancient, and comforting sense of the phrase, he now begins “to know what he is doing.” From: Wax, Rosalie H. (1971). Doing Fieldwork: Warnings and Advice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Module 1, Lesson 3: What Is Fieldwork Really Like? Student Handout #8: Doing Fieldwork Questions Name______________________________ Date______________ Pd__________ DIRECTIONS: Read Document #2, Doing Fieldwork, which accompanies these questions. Write answers to the questions below, using your own words. Identify any words in the document that you don’t know. 1. What are the three stages of fieldwork? ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ __________________ 2. What do you think are the EMOTIONS of a new fieldworker? Why? ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ __________________ 3. Does the author seem to suggest that first days in the field are easy or difficult? What examples does she give? ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ __________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ____________ 4. What does the author mean by “social limbo”? Give examples. ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ____________ ________________________________________________________________________ ______ 5. How is learning a new culture as an anthropologist like an infant becoming socialized? ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ____________ ________________________________________________________________________ ______ 6. Why are hosts, or trusted members of the new culture, so important to the anthropologist’s research? ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ____________