Mining in Northern Wisconsin

advertisement

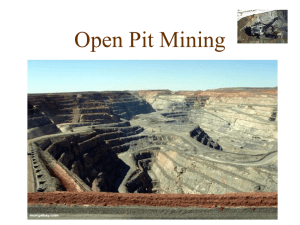

State Politics, Corporate Interest, and Native Rights: Mining in Northern Wisconsin Presented by Atty. Sandra Edhlund to the 18th Congress of the International Association of Democratic Lawyers. April 2014. The Penokee Hills of Northern Wisconsin stretch for 25 miles, roughly the distance between Brussels and Antwerp, or Liverpool and Manchester, or Tel Aviv and Gaza City. The Penokees and the land around them are the product of glaciers that receded thousands of years ago, leaving behind a complex grouping of streams, rivers, and wetlands that all deposit into Lake Superior, the largest of the United States’ Great Lakes. There are more than a dozen headwater lakes found in the Penokees, as well as the Bad River and its subsidiary waterways, which flow through the area’s forested hills before entering Lake Superior. There are also a number of ‘sloughs’ – essentially marshes – directly adjacent to the Penokees that, along with the headwater lakes and Bad River network, provide drinking water, fish and bird habitats, wild rice fields, and ground water displacement. From an ecological perspective, the Penokee Hills are not only an area of beauty in an increasingly industrialized world, but also a crucial part of the ecosystem of Northern Wisconsin. In addition to their environmental importance, the Penokees retain a spiritual and cultural importance to American Indian populations in the region. In particular, the Bad River Ojibwe, whose lands are situated in and around the Penokee Hills, attach incalculable historical importance to the lakes, rivers, streams, and especially sloughs of Penokees, where wild rice presently grows as both a food source and sacred plant. But there is one thing the Penokees hold – in addition to scenic beauty, ecological necessity, and tribal history – that appears poised change things dramatically: iron ore. -Northern Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan have long been mining country in one form or another. Modern copper mining arose in the Upper Peninsula in the 1840s and iron ore mining followed in subsequent decades. Town names – Copper Harbor, Copper City, Ironwood, Iron River, Iron Mountain, and so on – reflect the historical importance of the precious minerals in the area. By the turn of the 20th century, companies based in Chicago, Milwaukee and Minneapolis - all hundreds of miles away from the actual mines - were turning huge profits out of immigrant labor and readily accessible copper and iron. Port cities like Ashland, WI; Duluth, MN and Sault Ste. Marie, MI served as maritime hubs. Copper and iron were shipped across the Great Lakes to larger port cities like Chicago, Detroit, and Toronto, where the booming industrial economy hungered for the precious metals. As early as the 1910s, however, the mines began to slow down, as copper and iron ran out and the realities of supply and demand set in. Towns began to shrink at a dramatic rate, often by as much as 50 percent, leaving impoverished workers, the one-time labor force of the great mining operations, to fend for themselves. By the second half of the 20th Century, mining had ceased to be the economic engine of Northern Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula, though many residents did and still do long for the jobs it once provided. Simply put, there is not much copper and iron left to be mined, and therefore not many mining companies hiring, and therefore thousands of people out of work. But, as has recently been discovered, there is still iron ore in the Penokee Hills, which were left untouched by mining companies in the past. And in turn, there are people who would very much like to open the Penokees for mining and the money mining promises to deliver to them and their companies’ shareholders. -Leading the charge in the effort to mine the Penokees is the Gogebic Taconite Corporation (GTC). Founded in Florida less than five years ago, GTC is the brainchild of Chris Cline, one of the most powerful figures in American mining. Cline, who hails from West Virginia, made his early money in the coal business in his native state before branching out to operations in other parts of the country, most notably Illinois. With GTC, Cline and his partners now look to venture into the world of iron ore. Cline’s rise to power in the mining industry came at a time when so-called “clean coal” was emerging as America’s answer to a seemingly intractable conundrum: the country needed energy, the economy needed jobs, and the environmental impact of traditional mining could no longer be denied. Suddenly, the coal industry was operating in the 21st century. Mine shafts running hundreds of meters below ground and filled with soot-faced laborers constantly under threat of collapse (or fire, or toxic gas) were replaced by machines that literally removed the tops of mountains in order to access coal. Power plants belching black clouds into the atmosphere were replaced by newer, cleaner facilities. Skeptics maintained that there is really no such thing as “clean coal,” and that the environmental impact of mountaintop removal mining is devastating - diverting nearby streams, destroying forests and topography, and contaminating drinking water supplies in and around the mining zones. The mining companies, however, including Cline’s Foresight Reserves, quickly identified a winning strategy to trump environmental concerns: promise jobs, financially support politicians who do the companies’ bidding, and blame environmentalists for “job killing” policy aims when they voice opposition. It is a strategy limited neither to West Virginia nor to coal. In recent decades, as the American thirst for energy and valuable minerals has remained insatiable and the desire to become less reliant on foreign supply has grown, energy interests across the country have found friendly politicians and eager labor in equal measure. In North Dakota, for example, extracting petroleum via hydraulic fracturing – better known as “fracking” – has become the state’s primary industry. Along the Gulf of Mexico, conventional off-shore oil drilling continues to draw massive investment from global corporations. In the American Southwest and Rocky Mountains, natural gas is the subterranean resource of the day. Everywhere in the country, it seems, wherever there is a valuable rock or substance beneath the earth’s surface, whether related to energy production or not, there are companies looking to profit. But at what cost? Fracking in particular has come under intense criticism from environmental groups in recent years. Groundwater contamination, air pollution, and dangerous gas leaks have all been observed in connection with the practice. In addition, scientists believe there may be heath consequences to those living in and around the areas where fracking occurs – infertility, birth defects, and cancer, to name a few. But as environmentalists call for greater regulation, and as locals suffer and even die, the industry moves ahead and the mining companies rake in profits. What’s more, there are jobs to be had, whether in fracking, or coal mining, or working on an oil rig, or doing anything else connected to an ongoing, successful natural resource operation. At one point not too long ago, even the promise of jobs and cheap energy would not have been enough to overcome the protections of the Federal Environmental Protection Agency, as well as the various regulatory bodies and laws in place in each in individual state. If mining promised to cause serious, irreversible environmental damage, the EPA was supposed to say so, and to deny the mine’s permission to operate. Likewise, if a company arrived in a given state proposing an undertaking that threatened the wellbeing of the citizens, state governments were empowered to refuse permission to move ahead. The paradigm has changed, however, and the days of governmental protection from unscrupulous mining companies may now be in the past. Because recently, mining companies began to wonder: why bother complying with laws when we can just pay to have the laws changed altogether, and even write the new laws ourselves? Why should a company such as GTC, for instance, worry about Wisconsin’s long tradition of environmental conservation when an aggressively unconcerned Republican Governor and a Republican state legislature was encouraging them to make their own rules on the spot? -In late 2011, the Wisconsin Legislature introduced a new mining bill aimed at dramatically altering the legal and regulatory environment surrounding iron mining in Wisconsin. The timing of the proposed bill was no coincidence. Governor Scott Walker had taken office in 2010 promising to turn Wisconsin politics decidedly to the right. Funded by the infamous Koch brothers of Kansas, Walker announced that the state was “open for business,” backed a law stripping public employee unions of collective bargaining rights, and took aim at various social welfare programs designed to sustain the state’s poorest citizens. Walker pursued his policy goals with the fervent backing of the Republican-held state legislature, as well, which meant it was not entirely surprising when the 2011 mining bill became public. What was surprising, however, was the extent to which GTC had been involved in drafting a bill that in practice would apply solely to GTC and its efforts in the Penokee Hills, where it had recently purchased a large tract of land. By December 2011, journalists and concerned citizens were left to wonder: who exactly wrote the Wisconsin Assembly’s mining bill? The answer, it turned out, was not entirely clear, but there was no doubt that GTC had been heavily involved. The bill was written over the course of several months at the direction of five Republican state legislators, whose staffs worked in close consultation with GTC. Although official records do not detail the precise extent of GTC’s collaboration, all parties involved acknowledged that GTC – which claimed its mine would generate $1.5 billion (€1.15) in revenue – was involved. It is worthwhile to note that it was not illegal for GTC to offer input on the bill, and indeed Wisconsin Republican’s defended GTC’s role as a relevant party to the legislation. However, leading environmental groups were not consulted and a review of the bill suggests that GTC’s assistance in drafting a bill that would then govern GTC was quite extensive. Following the bill’s introduction, environmentalists and other concerned citizens began to express outrage at some of the changes proposed. To name a few of the bill’s proposed effects: -Removing protections for wetlands deemed Areas of Significant Natural Resource Interest -Weakening wetland mitigation requirements and allow superficial mitigation efforts to be considered as roughly equal to full restoration -Allowing mining companies to cause significant environmental impact on all streams and bodies of water not deemed to be part of the Great Lakes or the Mississippi River Basin -Requiring the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) to consider ‘economic benefits’ when deciding whether to issue water withdrawal permits -Stripping the Wisconsin DNR of authority to monitor mining sites for environmental risks -Removing the requirement that mining companies and the DNR study the nature and depth of ‘overburden’ on streams and bodies of water created by mining waste -Allowing waste piles to be 50% taller than under preexisting law, as well as to be placed in flood plains and shorelands -Removing the requirement that waste sites be placed, if possible, in areas that minimize environmental damage -Limiting the period of DNR permit review to less than a year -Removing the requirement that mining companies share data collected during their own environmental studies that could reflect negatively on the environmental impact of a proposed mine -Requiring that the DNR treat the scientific findings submitted by mining companies as sufficient to complete a mining permit application, even when the findings are incomplete and/or inaccurate -Exempting companies from mining taxes Given that the bill threatened to obliterate the existing regulatory scheme and allow for extensive mine-related pollution, the Democratic response was immediate and vocal. In turn, it soon became apparent in early 2012 that the bill would not become law in its original form. So GTC did what mining companies have grown accustomed to doing all across the United States: it posted a large sign in the Wisconsin Capitol Building announcing that it was leaving Wisconsin and never coming back – and taking the promises of jobs and money with it - unless the state legislature produced a law that was sufficiently GTC-friendly. Over the next year, Democratic legislators continued to voice opposition to the original bill while Republicans refused to offer meaningful compromise on key environmental issues. When a bi-partisan group of legislators produced an alternate bill, which would still have allowed for GTC’s proposed mine following regulatory and public approval, it was rejected by the Republican majority. Meanwhile, a group of Republicans split off to secretly marshal support for a practically unchanged version of the original bill, which they re-introduced in March 2013. On March 11, 2013, Wisconsin Act 1 – virtually the same piece of legislation that was drafted after extensive ‘consultation’ with GTC in 2011 – became law. With the legislative work done, the only remaining opposition to the law, and the mining the law seeks to enable, comes in the form of the Bad River Ojibwe, the American Indians who have lived in and around the Penokee Hills since before European settlement. Of course, U.S. history offers a fairly grim picture of what happens when corporate business interests come into conflict with native rights. And the current situation in Wisconsin threatens to be no different, as the GTC mine would appear to come into direct conflict with notions of tribal sovereignty and preexisting treaties between the government and the Bad River Ojibwe. The legal status of native American tribes in the USA is rather unique in that the tribes maintain their own police, schools, and courts subject only to federal government authority and not governed by the individual states. As the issues relating to the Gogebic mining proposal are being legislated by the State of Wisconsin for the area that is next to but not near the Bad River Band of the Ojibwe’s reservation, the focus of legal attention has been on the state law. The Bad River Band of the Ojibwe, headed by Chairman Mike Wiggins, has major reservations about the fast paced legislative moves to undercut both the legislative process and the appropriate testing to determine potential environmental damage to the watershed area and the reservation lands. In 2011, the Bad River Band became the third Wisconsin tribal community to seek authority from the federal government under the Environmental Protection Agency to set water quality standards for the reservation on the shore of Lake Superior. This power also allows the tribe to control pollution limits on other land outside the reservation that could harm tribal rivers, streams and wetlands. In August of 2013, Chariman Wiggins and five other tribal leaders petitioned President Obama to direct the Department of the Interior to prevent thte construction of the Gogebic mine. That request is currently pending. However, the federal response may be promising as the EPA has just refused a Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources request to jointly (do something-look it up) because of the disparity between Wisconsin’s new mining requirements and the stricter mining controls under the federal government. Central to the Ojibwe claim is the issue of testing the rocks in the area for environmentally dangerous minirals and for testing the effects of the extracting process on the water. The local tribes are interested in the testing and results and Gtac appears to be interested in keeping those private. Access or restricting accessto the area is an important issue. In May 2013, the Lac Courte Oreilles (LCO) Band of Ojibwe began to occupy their harvest camp in a five mile area, exercising rights they claim under an 1842 treaty with the U.S. The Wisconsin legislature responded by introducing another bill that would establish an exclusionary zone around the proposed mining site, while GTC reacted by hiring armed guards to keep citizens off the land under the threat of injury and even death. When it was discovered that the guards did not have permits to carry weapons in Wisconsin, they briefly departed, only to return shortly thereafter with now-legal weapons in hand. For now, the Penokee Hills remain the wilderness that they have been for centuries, but GTC would like to change that as soon as possible. Increasingly, as various statefederal issues work out and the company continues to prepare to break ground, it seems only a matter of time before open pit iron ore mining becomes the defining trait of the region. But there is still hope. Though the law has been enacted, the Bad River Tribe and a number of lawyers are working together to oppose the GTC mine. Should their efforts fail – and provided the U.S. government does nothing to stop the mine - streams will be diverted, polluted, and potentially eliminated altogether. Wildlife populations will see their habitats altered and in some cases entirely destroyed. Native peoples will find the wild rice fields that have nourished tribes since time immemorial replaced by chemical runoff and industrial waste. And it will all have been done under the auspices of a law vicariously drafted by the same company the law was meant to regulate, a company that bought its way to the table with money and promises of jobs and economic development. At some point in 2011, the Penokee Hills of Northern Wisconsin went up for sale, and GTC was happy to buy. Wisconsin Act 1 can be found at http://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/2013/related/acts/1