Character displacement annotated bibliography

advertisement

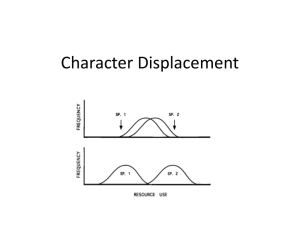

14 September 2011 Daniel Layton BIOL 6889 Space Seminar w/ Dr. Amy Zanne Character Displacement: Annotated Bibliography Introduction: Character displacement is a biological phenomenon in which two or more species in sympatry with similar characters (i.e. morphology, behavior, ecology, etc.) tend to evolve in opposite directions in order to reduce mutually harmful interactions. There are two major types of character displacement: ecological and reproductive. Ecological character displacement occurs in response to resource competition. Characters pertaining to resource use (e.g. jaw or beak size) and procurement will diverge when species are in sympatry so that a single resource is not being competed for. The two species in allopatry should thus have similar intermediate morphologies given the lack of competition. Reproductive character displacement occurs when there is selective pressure to reduce fitness-lowering interspecific sexual interactions, such heterospecific gamete transfer. Therefore, reproductive characters should be affected by this type of displacement. Proponents argue that character displacement is widespread and may be a major factor in adaptive radiations and speciation. Character displacement was first clearly defined in 1956, although the idea traces back to Darwin, and especially Lack, who studied Darwin’s finches in the first half of the 20th century. It quickly became a popular idea and many observational studies found patterns potentially consistent with character displacement. However, more robust statistical analyses later suggested that most of these apparent patterns were no different from chance. During this period, character displacement was believed to be rare and relatively unimportant. In 1992 Schluter and McPhail published an important list of six criteria that needed to be met in order to convincingly tie a observed pattern to character displacement. From this point onwards, studies tended to be more thorough and interdisciplinary in order to meet these ‘requirements’, and experimental studies also began to emerge. There are currently over 100 published studies on character displacement, and there seems to once again be consensus that it is an important phenomenon, although the difficulty of tying pattern to process remains. Annotated Bibliography: Adams, D. (2010). Parallel evolution of character displacement driven by competitive selection in terrestrial salamanders. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 10, 72. Adams addresses the possibility of multiple sympatric zones experiencing the same morphological character displacement pressures; in other words parallel evolution of character displacement. He examines three transects, each containing three populations of salamanders where two are separate species in allopatry and the third is the same two in sympatry. Data are based on the morphology of the head, with each specimen being tied to its locality and whether or not it co-exists with another species. Various statistical analyses, including MANOVA and PCA, are used to analyze the data. The results suggest each replicate transect had the same morphological differences in the same directions in the sympatric populations versus the allopatric ones. The weakness of this paper was that it did not convincingly demonstrate that these different morphologies were due to character displacement and not some other factor, such as the elevation, which would have also correlated similarly with the patterns observed. Its strength and significance lies in its attempt to connect parallel evolution with character displacement, which seems highly plausible and worth further investigation. Armbruster, W.S., Edwards, M.E. & Debevec, E.M. (1994). Floral Character Displacement Generates Assemblage Structure of Western Australian Triggerplants (Stylidium). Ecology, 75, 315-329. This study aims to tie species assemblage structure in a group of 31 species of plants with character displacement. The data are floral measurements in order to characterize niche structure, number of visits to flowers at various levels of receptivity, location of pollen placement and pollen color. The authors find that find that the low overlap in niche type (a conglomerate measure of column length, column reach, and nectar tube length) is lower than that expected by chance, and that character displacement is more likely than ecological sorting based on a null model comparison. The strength of the paper is its broad sampling and exhaustive modeling. The paper’s obvious weaknesses are that it does not demonstrate directly that competition exists and it does not give enough evidence to show if pollination morphologies are heritable, although this is likely. It’s significance lies in its suggestion that character displacement may be a very important phenomenon in adaptive radiations, at least in some groups. Brown, W.L. & Wilson, E.O. (1956). Character Displacement. Systematic Biology, 5, 49 -64. Brown and Wilson present and define the concept of character displacement (and its opposite: character convergence or release) as a common biological phenomenon for the first time, citing numerous examples from their own work as well as the literature. It addresses in particular many cases where hybridization was initially suggested to explain convergence in allopatry, but given noticeable divergence in sympatry, the authors believe character displacement to be a more plausible explanation. Data are derived primarily from other studies, but also includes some original work. Data center always around various character measurements (usually ones related to feeding) as they interact with biogeography. Data are presented from birds, ants, fish, frogs, beetles, and crabs. The authors find that a pattern consistent with character displacement is common in many species in diverse environments and geographical locales. The paper presents a strong case due to this similar pattern having been observed frequently and diversely, but its weakness is that pattern is emphasized and process is only speculated at, if at all. Furthermore, data are nearly always morphological, not ecological, behavioral, etc. Nonetheless, this paper defined the field by presenting a common biological pattern. Grant, P.R. & Grant, B.R. (2006). Evolution of Character Displacement in Darwin’s Finches. Science, 313, 224 -226. Here character displacement in Geospiza finches on the island of Daphne Major in the Galápagos is supported from start to finish by 33 years of data. It focuses specifically on a severe drought in the presence of a new competitor that led to strong morphological changes in the opposite direction that previous droughts had produced. Various measures of bill dimensions, body size, diets, weather, population size, each taken each year, comprised the data. Geospiza fortis, which initially lacked close competitors on the island and had thus evolved a beak allowing it to be a generalist seed eater, was later subject to competition from Geospiza magniostris, a bird about twice as large and specializing on larger seeds. Competition produced no measurable impact until a severe drought 22 years after the establishment of G. magniostris, which led to nearly a full SD reduction in beak size for G. fortis due to intense competition and high rates of starvation in both species. The huge amount of data and the strongly significant results are very strong points. Perhaps the lack of genetic data to back up their determinations, especially considering they are dealing with morphologically overlapping species, can be considered a weakness. This paper, in the words of the authors, is the first line of evidence for character displacement “from the initial encounter of competitors to the evolutionary change in one or more of them as a result of directional natural selection”, making it exceedingly important for the field. Le Gac, M. & Giraud, T. (2008). Existence of a pattern of reproductive character displacement in Homobasidiomycota but not in Ascomycota. J. Evol. Biol, 21, 761-772. This paper examines the literature for evidence of potential reproductive barriers in experimental crosses of fungi in pairs of species that are either allopatric or sympatric. The authors consider evidence of reproductive isolation in sympatric species as a potential corollary for reproductive character displacement. Data include genetic distance based on Genbank resources, a reproductive isolation index based on percentages of successful crosses, phylogenetic information, and ecological data. The study finds that premating isolation is greater amongst sympatric species pairs of homobasidiomycetes versus the allopatric pairs in their sample, but no such pattern occurs in ascomycetes. This suggests some unknown trait of the former may help to promote character divergence that the latter lacks. They also find that reproductive isolation is correlated with genetic distance in allopatric homobasidiomycetes, but not in sympatric species pairs. The major weakness of the paper was a lack of investigation into character divergence itself. Identifying reproductive isolation is only one of many criteria necessary to convincingly suggest character displacement is taking place rather than some other phenomenon. The paper’s strong point is it use of good genetic data and a relatively high sample size. The fact that some life history component of a large higher grouping of fungi may be responsible for promoting vs. repressing sympatric reproductive isolation makes this paper significant. Whether or not particular biological groups are prone to character displacement has been much discussed, but very rarely suggested with evidence. Losos, J.B. (1990). A phylogenetic analysis of character displacement in Caribbean Anolis lizards. Evolution, 558–569. Losos tests for character displacement (here often called ‘size adjustment’) versus presumed competitive exclusion (or ‘size assortment’) in a genus of lizards which have diversified on 27 islands. Specifically, he tries to explain why islands with two species always have one large species and on small species, while islands with one species always have an intermediately sized species. The paper marks an important early use of phylogenetic data (based on immunology, electrophoresis, karyology, and morphology) to answer an ecological question. These data were then analyzed with various algorithms and statistical tests. His models support character displacement in the northern islands but not in the south, and a separate analysis indicates competitive exclusion played a role on all islands. Unfortunately, his phylogeny has multiple polytomies, is based on outdated techniques, and is compiled from multiple sources, suggesting the true phylogeny would look substantially different if repeated with modern methods, thus changing the results of the analyses in kind. In the discussion he acknowledges this, but argues some evidence is better than no evidence. The paper’s strong point, as well as its significance in the field, is its acknowledgement that current ecological conditions alone cannot be expected to explain a fundamentally historical process; phylogeny must be integrated. Losos, J.B. (2000). Ecological character displacement and the study of adaptation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97, 5693 -5695. This paper summarizes the state of character displacement research, and also looks at a case study with two species of eastern North American salamanders. The data from the case study include morphological measurements of the jaw in allopatric and sympatric populations and surveys of insect prey availability to demonstrate similar resource availability in both situations. The results of this case study suggest that competition led one species to become smaller and focus on smaller prey and the other to become larger and focus on larger prey. The paper also argues that character displacement studies have only recently overcome something of a technology barrier due to the multi-disciplinary approach required to convincingly show that character displacement has occurred. It also reviews these criteria in the context of the case study. This paper (and moreover the corresponding study, Adams and Rohlf 2000) is strong in that it is able to demonstrate that competition for a limiting resource is the driver of a morphological change clearly tied to that competition. Its weakness is it failure to incorporate genetics or show that the morphological characters of interest are heritable. The study’s significance lies in its correlation of what seems at first glace to be an unimportant morphological trait with resource competition on closer inspection. Marshall, D.C. & Cooley, J.R. (2000). Reproductive Character Displacement And Speciation In Periodical Cicadas, With Description Of A New Species, 13‐Year Magicicada Neotredecim. Evolution, 54, 1313-1325. Marshall and Cooley examine potential reproductive character displacement in two species of cicada in which the decibel level of mating calls diverge when the species are sympatric but are similar in allopatry. Data include field surveys of range overlap, call recordings, measures of female preference, and morphological measurements. The study finds a strong relationship between morphology and call pitch, as well as female preference for one or the other of these calls, confirming the presence of two species. They also find that in allopatry, the pitch of one species’ call drops from 1.7-1.9 to 1.4-1.5 kHz, but the other species call remains constant in both allopatry and sympatry at 1.1 kHz. Female preference co-varies male pitch changes. The strength of this paper was simultaneous recognition of a new species coupled with data suggesting character displacement. Sampling was also quite strong considering the once-in-13-years opportunity to examine the species of interest. One weakness was that the authors only had time to characterize allopatric vs. sympatric characters in one of the two species. The paper is significant because it is one of the few examples of character displacement in insects. Muchhala, N. & Potts, M.D. (2007). Character displacement among batpollinated flowers of the genus Burmeistera: analysis of mechanism, process and pattern. Proc. Biol. Sci, 274, 2731-2737. Muchhla and Potts explore the notion that the reduction in fitness caused by interspecific pollen transfer may be a driver of character displacement in flowering plants. They examine bat-pollinated plants in the neotropical genus Burmeistera, looking at the distribution of anther exertion as the character potentially being displaced. The important data is of two types: (1) distance from the end of the anther to the point of petal fusion for 19 species of Burmeistera encountered in 50 populations in 18 cloud forests; and (2) interspecific pollen transfer rates for a variety of species pairs obtained using caged bats and manipulated flowers. The cage experiments were later correlated with wild measurements. The results support the idea that greater anther exertion differences between species reduce interspecific pollen transfer. Comparisons with null models also indicate the mean exertion differences are overdispersed compared with random expectations. This paper’s strength is its combination of experimental and observational data to demonstrate the existence of competition and character displacement. However, the experiments are also its weakness: they do not demonstrate that significant loss of fitness is caused by the presence heterospecific pollen transfer, however plausible this might be. The paper is significant because it suggests that reproductive competition may be a major driver of speciation via character divergence in flowering plants. Pfennig, K.S. & Pfennig, D.W. (2005). Character displacement as the “best of a bad situation”: fitness trade-offs resulting from selection to minimize resource and mate competition. Evolution, 59, 2200-2208. This paper addresses the balance between potential benefits of character displacement (i.e. reduced competition) with potential downsides (i.e. reduced fitness) in two sympatric species of spadefoot toads. The authors aim to determine if the two species differ in size due to character displacement, if so why, and finally whether this has impacted the fitness of one or both species. Data include clutch size for fitness measures, adult length for morphological character displacement analysis, mtDNA allozymes for species identification, and survivorship numbers in identical aquarium conditions. The study shows a significant difference in size between the two species in sympatry as well as lower survivorship and reduced clutch size for the smaller species. The paper’s strength lies in its combination of observation and experimentation to attempt to answer a novel question about the potential negative “side-effects” of character displacement. A potentially large flaw in the study was the use of mtDNA allozymes for tadpole identification. Because mtDNA is maternally inherited and because hybridization is known to occur between these species, this is likely a rather poor method of identification. Furthermore, they equate reduced clutch size with lower fitness, which is not demonstrated. The paper is important in the field because it examines character displacement more holistically by looking at potential negative pleiotropy. It also introduces a limited (albeit imperfect) use of genetics to confirm tricky species identifications. Reifová, R., Reif, J., Antczak, M. & Nachman, M.W. (2011). Ecological character displacement in the face of gene flow: evidence from two species of nightingales. BMC Evol. Biol, 11, 138. This study addresses ecological character divergence in sympatric species where hybridization and gene flow are still occurring. The paper seeks to determine to what degree, if any, species must be reproductively isolated before ecological character displacement can take place. The authors use two Z-linked (i.e. sex linked for birds) nuclear genes in order to detect hybrid males in a genetic sample, as well as morphological measures for body and bill size. The results show that body size converges but bill size diverges in sympatry despite evidence of at least 3% hybridization. Controlling for latitudinal shifts in morphology, the body size convergence is shown to be an environmental effect, while bill size divergence remains better explained by displacement. They also find evidence of displacement as opposed to character sorting by comparing the range of allopatric and sympatric variation. The use of z-linked genes for haplotyping and environmental controls in the statistical analyses were a strong point of the research. The rather crude quantification of hybridization was a weak point; better work in this area would have made the results much more interesting. Overall, the paper is significant because it provides a robust observational example of character displacement despite the fact that hybridization is known to occur. Rice, A.M. & Pfennig, D.W. (2007). Character displacement: in situ evolution of novel phenotypes or sorting of pre-existing variation? J. Evol. Biol, 20, 448459. This paper asks if an invading species vs. an invaded species is more or less likely to ‘win’ during asymmetric character displacement. That is to say, when displacement leads to mutually exclusive use of two unequal resources by two species, is one more likely to get the better resource than the other? The authors examine two species of spadefoot toads to attempt to answer this question. The data are 663 bp of cytochrome b mtDNA for haplotyping, assessing genetic diversity, and reconstructing ancestral distributions. Spea bombifrons has low haplotype and nucleotide diversity, shows no isolation by distance in an IBD analysis, and a coalescent-based analysis shows high population growth. S. multiplicata shows opposite trends. This is a strong paper because of its use of population genetics, a powerful tool underutilized in the field. The weaknesses lie in the deceptive question it claimed to address (a study of two species cannot tell us if invaders are more commonly ‘winners’), and its use of only 663 bp of genetic material from the mitochondrion, which, as it were, only tells a small part of half the genetic story. The significance of this approach is that it has the potential to bridge invasive species biology (a study largely of the present) and speciation studies (a study largely of the past and future), potentially leading to the ability to make predications about how speciation might proceed given contemporary widespread introduction of invasives. Schluter, D. (1994). Experimental Evidence That Competition Promotes Divergence in Adaptive Radiation. Science, 266, 798 -801. British Columbian Stickleback fishes were examined experimentally in artificial ponds in order to provide direct experimental evidence of character displacement. A generalist species occurring alone in nature was subjected to the presence of a limnetic specialist, the latter naturally occurring with a benthic specialist, from which it was believed to have separated via character displacement. The author expected generalists with more limnetic characters to be most severely impacted by competition with limnetic specialists. The data are experimentally derived and consist primarily of a number of morphological measurements to assess growth rate taken at the beginning and end of the 90-day trial. The experiment found limneticleaning generalists were most strongly affected by competition with limnetic specialists as reflected by a much reduced growth rate in the former. The use of an experimental approach was the paper’s strong point. Two weaknesses were the short duration of the experiment and the fact that growth rates and not mortality rates were shown to have been caused by competition. Nonetheless, the fact that an experimental approach was brought to the field through this study makes it a landmark paper. Schluter, D. (2000). Ecological Character Displacement in Adaptive Radiation. The American Naturalist, 156, S4-S16. This work assesses existing research on character displacement by performing a meta-analysis on 61 published studies. The paper also assesses progress in the field, searches for commonalities between studies, and reviews the author’s experimental work on stickleback fishes. The data include character ratios and displacement symmetry ratios obtained from the literature, as well as statistics on the number of published studies meeting six criteria laid out to assess how well character displacement has been demonstrated. He finds that divergence is greater where divergence is also symmetrical (i.e. affecting both competitors), that carnivores are overrepresented in the existing studies, and that a demonstration of competition is the most likely factor to be missing from a character displacement study. The paper makes a thorough critique of existing work and points out the more experimentation and demonstration of competition is needed. The focus on the author’s own work at the expense of others could be seen as a weakness, as could his omission of examples that counter rather than support character displacement. The paper’s most significant contribution to the field is likely its recognition that observation alone cannot be relied upon to convincingly demonstrate character displacement in most cases. Smith, R.A. & Rausher, M.D. (2008). Experimental evidence that selection favors character displacement in the ivyleaf morning glory. Am. Nat, 171, 1-9. Smith and Rausher examine character displacement due to reproductive competition in plants. Because one species of morning glory (Ipomoea purpurea) can reduce fitness in another species (I. hederacea) by producing sterile hybrid seeds where they co-occur, the authors test with a selection analysis whether character displacement occurs to reduce hybridization in sympatry vs. allopatry. Data include flower number per plant, several floral measurements, and fitness values based on seed set for two different treatments (exposed to interspecific pollen or not). The selection analysis found directional selection in I. hederacea when it was exposed to I. purpurea pollen, but no directional selection in its absence. Stigma position and anther position were both selected in such a way as to potentially increase selfing and increase anther coverage of the stigma. The well-planned experimental design that accounted for confounding environmental factors was a strength, while the lack of second or third generation plants in the study was a weakness. The experimental demonstration of directional selection in plants in sympatry, but not in allopatry is significant because previously almost all character displacement studies were animal centered. Conclusion: As mentioned in the introduction, studies of character displacement have seen a major resurgence in the last two decades. Nonetheless, much remains to be done, and further integration of diverse methods will be the key to further solidifying the theory. For example, population genetic approaches have only very recently been adopted, but their explanatory power for evaluating competitive interactions, how sympatry might have arisen, and genetic structure in sympatric species groups is potentially huge. Phylogenetics has also been largely neglected in observational studies of community assemblages, perhaps due to cost and time constraints, although this should change in the future. Phylogenetics, like population genetics, helps to get at the historical context for character displacement, which is unknowable from direct observation alone. Finally, experimentation has only recently been shown to be a powerful tool in the field, and surely further experiments will serve to provide more direct evidence of character displacement while complimenting the wealth of observational data.