apacomments - Feminist Philosophers

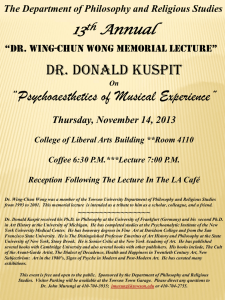

advertisement

“Is this really the topic of the conference?” Jason Stanley Draft of December 28, 2013 My remarks today are not original. They are elaborations of the points made in Kristie Dotson’s 2012 paper in the journal Comparative Philosophy, called “How is this paper philosophy?” Dotson’s paper is a brilliant paper in political philosophy that takes as an example the various strategies used in philosophy as mechanisms of subordination. I’m going to emphasize the descriptive and prescriptive accuracy of her points about the field. But I’ll also try to bring out its importance as an analysis of how mechanisms of subordination are employed in competition over resources, and in particular the role normative language plays in enforcing entrenched structures of dominance and subordination. Dotson makes a point about the culture of philosophy that is correct. She then recommends a solution that is also correct. Here is the insight Dotson brings our attention about the culture of philosophy, and her suggested solution. Dotson points out that the boundaries of philosophy are heavily policed. The question, “how is this philosophy?” is one that all of us who have served on hiring committees have heard or made ourselves. She calls this “privileging legitimation narratives”. She argues that the extensive policing of the boundaries of philosophy is a sign that the discipline allows too much space for implicit bias. She recommends instead what she calls “a culture of praxis”, which she characterizes as: . (1) Value placed on seeking issues and circumstances pertinent to our living, where one maintains a healthy appreciation for the differing issues that will emerge as pertinent among different populations and . (2) Recognition and encouragement of multiple canons and multiple ways of understanding disciplinary validation. In what follows I will explain the basic problem to which Dotson brings our attention, and motivate her prescriptive solution. Because I can’t help it, I will also situate it as a contribution to the small but insightful literature in political theory that argues how normative concepts are especially susceptible to abuse as strategic instruments in battles over resources. Section I. The Nature of the Problem This year is the middle of my 20th year as a professor of philosophy. During this time, my social life mainly involved professors in neighboring humanities and social sciences disciplines. Here are are three salient distinctions between philosophy and the other disciplines. (1) In other disciplines in the humanities, social sciences, and psychological sciences using actual examples of social injustice as premises for a theoretical argument is not a barrier towards employment in the very best departments. (2) In many such disciplines, consequential breakthroughs were made by members of once marginal groups in that field. Furthermore, it is clear that in many cases membership it was precisely the distinctive epistemic vantage point provided by membership in these historically excluded groups that allowed for the relevant field-changing insights. (3) Such fields do not have the same barriers to access for politically disadvantaged groups that philosophy seems, for whatever reason, to possess. The presence of groups not adequately represented in philosophy is much less of an anomaly. These three distinctions are of course related. Philosophers do not like comparisons between philosophy and other humanities and social science disciplines. We widely regard ourselves as holding to standards that are considerably higher than those in other humanities disciplines, standards that are more akin to, for example, fields such as psychology. In the face of this fact about our assumptions, it is a mistake to change minds by appeal to ordinary practice in for example French Literature or Comparative Literature. I propose then to bring out the problem by contrasting philosophy with the discipline of History. History is a field with extremely high intellectual standards. Serious work in history takes facility with archival research, and intense care about one’s claims to avoid easy refutation by empirical fact. History is also an extremely competitive field, with many job candidates for each opening. Given the ratio of PhDs to jobs, competition for jobs at the leading departments must be reckoned to be as competitive as in any major field. Yet despite the obviously very high intellectual standards required for professional success, History departments clearly differ from philosophy departments along all three measures we have discussed. The other day I took my three year old son to the playground. It was a very cold day in New Haven, and the only people on the playground besides my son and me were a woman and some children she had brought there. Recognizing her from Yale College Faculty meetings, I struck up a conversation. It was Beverly Gage, of the Yale Department of History. Yale’s History department is widely regarded as the leading History Department in the country. Gage works on American political ideology. Her first book, The Day Wall Street Exploded, was about the state coercion surrounding class tensions during the gilded age. She continues to work on ideology, and her newest book project is about J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI. Adorno famously defines ideology as “necessary false consciousness”. There are various different ways of making this precise.1 One way to think of propaganda is as the There are also less negative senses of “ideology”. In Chapter 1 of Raymond Geuss’s The Idea of Critical Theory: Habermas and the Frankfurt School (Cambridge: Cambridge 1 conscious attempt by means of various rhetorical devices to instill an ideology in a subordinate class, paradigmatically (though not necessarily) carried out by those in power as an instrument of cohersion and control, to maintain their power.2 Professor Gage did not ask me about who was working on ideology and propaganda in what on some views would be regarded as leading philosophy departments. It would only be possible to list a few names in response. Tommie Shelby has written subtle and brilliant articles on ideology, such as “Ideology, Racism, and Critical Social Theory” (Philosophical Forum 34, 2003, 153-188). Shelby’s work is notable for its attempt to argue for the compatibility of ideal democratic political theory and the multiple traditions of ideology critique one could locate in both the United States, in the work of Du Bois, and in Europe, principally the Frankfurt school. For example, Shelby has written a reply to Charles Mills’s masterwork, The Racial Contract (Cornell University Press, 1997) that tries to fit ideology critique together with ideal political theory. Elizabeth Anderson has been working on the topic for many years. To my knowledge, the most important and sustained attempt by an American philosopher to move past gross characterizations of ideology and provide some structure for it is by the MIT philosophy Professor Sally Haslanger. Haslanger has been working on this topic intensively for over a decade, marshaling the full resources of the philosophy of language to explain the phenomenon. Haslanger is after what Raymond Guess calls “ideology in the descriptive sense”. Though her views about the metaphysics of social kinds have changed over the years, she does return repeatedly to what she has always regarded as “the basic sense of ideology”, “ideologies are representations of social life that serve in some way to undergird social practices.” You can see in her work a sustained-multi year attempt to place structure on ideology. In her 2007 paper, “BUT MOM, CROP-TOPS ARE CUTE!” SOCIAL KNOWLEDGE, SOCIAL STRUCTURE AND IDEOLOGY CRITIQUE”, she appeals to relativism to explain the phenomena; in later papers, such as her 2012 Carus lectures, an externalist meta-semantics takes its place.3 Her recent colleague Rae Langton has also contributed a great deal to the systematic study of ideology critique, and Jennifer Saul’s work on the topic is starting to emerge. Miranda Fricker 2007 book, Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing (Oxford: Oxford University Press) is an important recent contribution. There is also a “positive rhetoric tradition”, exemplified by Melvin Rogers as Emory University, using Du Bois as an example.4 What is interesting about these philosophers is that all of them were led to University Press) distinguishes three senses of “ideology”; ideology in the pejorative sense, ideology in the descriptive sense, and ideology in the positive sense. It has proven difficult to characterize the relevant sense of “false consciousness” (see the first two chapters of Michael Rosen, On Voluntary Servitude: False Consciousness and The Theory of Ideology (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1996)). For this reason those writing on the topic tend to focus on ideology in the descriptive sense, as in the work of Sally Haslanger. 2 See e.g. Rosen (1996, p. 52). 3 See Haslanger’s Resisting Reality: Social Construction and Social Critique (Oxford: OUP, 2012). 4 American Political Science Review, 106.1 (February, 2012): 188-203 the project by reflection about their own situation as members of marginalized groups. It’s worth emphasizing how large a lacuna in the field the study of ideology is. At Yale, explicitly influenced by Adorno and Arendt, Stanley Milgram did his famous experiments on obedience to authority, one of the foundational discoveries of social psychology.5 Adorno’s work on ideology continues to guide serious research in the psychological sciences; it is essential reading in central areas of social psychology. As the psychologists John Jost, Christopher Frederico, and Jamie Napier note in the abstract of their useful 2009 review article on the psychological study of ideology, (“Political Ideology: Its Structure, Functions, and Elective Affinities”, Annual Review of Psychology 60:307-337), “Ideology has re-emerged as an important topic of inquiry among social, personality, and political psychologists.” Though its definition and characterization are heavily contested, something like ideology, in the sense of the study of the implicit assumptions that guide and structure our social behavior is central to many disciplines. If philosophy is the study of the foundational concepts that reveal the human condition, then it would be bizarre it did not include ideology. Yet if it were not for the work of members of underrepresented groups in philosophy, it is as if this subject area did not exist as a philosophical topic (and of course that fact itself is a datum for an “ideology critique” of philosophy). The work done by in philosophy on this topic is excellent. However, we cannot credit ourselves. Most of those who work on the topic, such as Haslanger and Langton, earned tenure as analytic metaphysicians and historians, thereby permitting them to “branch out” to a topic that is not discussed in philosophy, but central to virtually all areas of human inquiry. It is difficult to imagine a junior candidate with a dissertation on ideology and propaganda landing a job in a top department, except in the rare case in which a top department is seeking to fill a slot in a marginalized area, such as so-called “continental philosophy”. Compare the situation to History. The named chairs in Yale’s elite history department include at least four figures working mainly on African-American history, one figure working in Lesbian and Gay History, another on Native American History, and someone working on both African American history and Women’s History. Multiple newly minted PhDs hired into the department work on nationalism, ideology, gender, and race. The three upcoming events listed in Yale’s history department are a lecture by a Princeton History professor entitled “Radical Relations: Lesbian Mothers, Gay Fathers, and their Children in the United States Since World War II”, a symposium on the topic “Free Love, Free-Markets: Histories of Capitalism and Sexuality” and a lecture entitled “Charity and Sylvia: A Same-Sex Marriage in Early America”. Nor is History univocally oriented towards what some may consider a leftist direction. Niall Ferguson’s work is mainly devoted to defending the worst excesses of imperialism. He too is a respected Milgram, Stanley (1963), “The Behavioral Study of Obedience”, Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 67 (4): 371–8. 5 historian, at Harvard. Historians of gender and slavery co-exist pleasantly at Yale as colleagues with historians of Western Europe and ancient Rome. The fact that leading History departments seek out the perspective of historically marginalized groups reflects the reality of the impact of the work by members of such groups. Consider for example the effects on the discipline of of W.E.B. Du Bois’s 1935 masterwork, Black Reconstruction. Du Bois there argues against the then prevailing view of Reconstruction that its failure was due to the unpreparedness of blacks for managing their own affairs, that the failure was instead due to the white upper classes’s efforts to ensure that white and black workers would not unify interests to promote labor rights. Du Bois’s work was widely rejected by historians, until the 1960s, when it was recognized that Du Bois’s study of Black Reconstruction was much accurate than the prevailing view. Historians were left to face the obvious conclusion that racism had masked itself with the vernacular of objectivity. Because of Black Reconstruction and other works, such as The Souls of Black Folks, Du Bois is a major figure in multiple disciplines, including history, sociology, and political science. He is however a marginal figure in philosophy. Even the philosopher Alain Locke, who was a central figure in professional philosophy for his entire lifetime, is not widely studied in leading philosophy departments, though he is widely studied in other disciplines (though see Leonard Harris’s edited collection, The Philosophy of Alain Locke, Harlem Renaissance and Beyond (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1989), and Jacoby Carter’s Stanford Encyclopedia article). The work of feminist historians was equally important in awakening historians to the fact that there are other features of history besides war. In short, the field of History clearly reflects the view that the study of oppressed groups is a source of potentially great theoretical insight. Finally, though History still is not perfect, comparing the representation of blacks and women in leading departments to the representation of blacks and women in philosophy is embarrassing. Dotson’s paper is a brilliant contribution to ideology critique. Using her own discipline, she explains how the mechanisms of control function to keep the discipline in the hands of the group that has traditionally controlled it, white men. It is also a very important contribution to moral and political theory. Dotson uses the field of philosophy as a demonstration of the special role normative language plays in subordination and control. This has important ramifications for moral and political theory. For example, according to “ideal political theory”, the goal of political philosophy is to describe an ideal conception of a state that perfectly realizes the ideals of justice. In Political Liberalism, Rawls is clear that the ideal conception is to play a practical role in the project of Public Reason in an actual states seeking to become more democratic (Rawls, 1993, pp. 86-7). Habermas has a similar view. If Dotson is correct that normative language has a special role to play in subordination and control, then there is a serious problem about pursuing political philosophy in this manner. As Melvin Rogers has reminded me (p.c.), advocates of non-ideal theories are usually just advocating a less rationalistic version of ideal theory. Instead of relinquishing ideal conceptions as playing a guiding role, they allow the ideal reasoning to include appeal to explicitly moral concepts or emotions.6 Dobson’s challenge to ideal theory is more foundational.7 If we cannot appeal to moral and political notions in Public Reason, it is hard to see how any ideal of Public Reason is feasible. Section II. Ideology critique and implicit bias Pierre Bourdieu is hardly ever mentioned in departments of philosophy, despite the fact that Google Scholar records over 300,000 references to his work. A central theoretical concept he employs in his analysis of ideology is that of the habitus. The habitus is a collection of habits that we employ usually unconsciously to navigate our social world. Bourdieu uses the habitus to explain a distinctive feature that is possessed by cases of ideological false consciousness. It is not possible to undermine practices based on ideological false consciousness by rational reasoning and deliberation. The person committed to viewing Americans blacks as genetically less intellectually gifted will not see the contradiction in his behavior when he treats for example African blacks differently. In The Logic of Practice, Bourdieu uses this feature to argue that the social practices that paradigmatically exhibit false consciousness are not mental states. The American philosopher who has to my knowledge provided the clearest alternative picture of the source of false consciousness is Tamar Gendler, in her well-known work on Alief (“Alief and Belief”, Journal of Philosophy, 2008, “Alief in Action and Reaction”, Mind and Language, 2008). Gendler argues that we must recognize a new mental state, indeed a new propositional attitude, which she calls “Alief”. According to Gendler, the attitude of Alief guides much of our social behavior; positing it explains such behavior. But since it is not accessible to consciousness, it is not subject to rational revision. Peter Railton has defended the view that social practices are beliefs, holding that failure to do so frees for example the racist from blame; in my own work, I also treat social practices as beliefs, and argue that certain very central beliefs to the mechanism of our social functioning cannot be rationally dislodged. As is clear from her 2012 Carus lectures, as well as her trenchant criticisms of a purely cognitive account of ideology, found also in Langton, Haslanger has increasingly more forcefully aligned herself with Bourdieu’s view. It is not important for our purposes to decide on this otherwise very critical philosophical question. We need some concept that plays the right explanatory work. Social practices cannot be altered by intervention in the form of deliberation and reason. That is something that requires explanation. The example Gendler gives is racism. Implicit attitudes towards race control our behavior in ways that we cannot or will not see. Bourdieu in contrast does not chose to see practices as propositional attitudes, even 6 For the first, see Amy Guttman and Dennis Thompson, Democracy and Disagreement. (Belknap Press, 1998). For the second, see Sharon Krause, Civil Passions: Moral Sentiment and Democratic Deliberation (Princeton: Princeton University Press). 7 In my forthcoming book, The Noble Lie: Why Propaganda Matters, I pursue a similar criticism of ideal theory. novel ones of the sort Gendler describes. Both accounts are designed to explain something that is hard to deny. There are patterns of behavior that cannot be dislodged by reasonable deliberation. The model of reasonable deliberation from John Rawls and Jurgen Habermas does not fit such cases. In fact, someone who assumes that it is mutually assumed that the model of reasonable deliberation fits such cases will be at a systematic disadvantage to the one who does not. Like Gendler, I reject a behavioral account of practices of the sort that is suggested by Bourdieu’s habitus. My own view is that one doesn’t have to abandon the cognitivist position that these states are beliefs to explain the fact that they cannot be undermined by rational deliberation. What Jennifer Nagel calls “settled belief” is very difficult to undermine by deliberation deliberation. I do think there is a category of beliefs that guides our behavior that is central to our belief system, but about which it is easy to be self-deceived, to believe it, without believing that one believes it. Whether implicit beliefs are aliefs or beliefs is irrelevant. What is relevant is that they are firmly held, certainly in the face of clear, very high statistical likelihood of their falsity. Let’s call these “implicit beliefs.” Haslanger and Langton have good arguments against such a way of thinking of the source of our social practices. But for now I am choosing the vocabulary of belief because it is the easiest one in which to state Dotson’s point. I am sure there is a way of recasting the point in terms more friendly to Haslanger’s conception of social practices. Supposing that our social practices are guided by implicit beliefs, it is not hard to see that it would be especially easy to align these beliefs with one’s sense of justice. For example, the process of self-justification in the face of awareness of possession of those beliefs plausibly involves a conscious such alignment. If I may indulge in a bit of introspective phenomenology, in the many times in my life when I have acted on sexist and racist beliefs, it is because I felt a special twinge when certain assumptions of mine were upset, for example that it was not fair that a woman occupied a role in the power structure that was rightfully mine. The twinge reflected my automatic reaction that my sense of justice was violated. But my sense of justice in these cases was nothing other than my underlying assumptions about the structure society is expected to take. As an American, I expect the various goods of society to go to me first, as a white man, and when these expectations are upset, it yields disequilibrium that is easily mistaken for a detection of a violation of fairness. If it is true what we have learned, that justice is fairness, then it’s easy to misperceive such disequilibrium as unjust. This point requires no dramatic psychological assumptions. It is easy to see how pre-conceived notions of how society is supposed to be structured, according to what one’s personal path through the social world has led one to expect, with can be unreflectively mistaken for a conception of how society ought to be structured, if it is to be free of oppression and coercion. In his massive tomb, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change (Cambridge, Harvard University Press), Randall Collins reminds us that philosophy is and always has been a competition for scarce attention space. When one adds to that the scarcity of resources, of professional positions, one has a political situation. Battles over resources are what the philosopher Elizabeth Camp calls in forthcoming work, “antagonistic situations” (see also the discussion of “strategic action” in Jurgen Habermas’s “Some further clarifications of the concept of communicative rationality”, in his On The Pragmatics of Communication (Cambridge, MIT Press): 307342). In such situations, we cannot rely on words being used straightforwardly.8 Moral and political terms are most often brought to bear in the resolution of political conflicts. Political conflicts most often take the form of struggles over limited resources, where one party, the one already with the resources, seeks to retain the upper hand. In his 1927 book, The Concept of the Political, Carl Schmitt argues that: All political concepts, images, and terms have a polemical meaning. They are focused on a specific conflict and are bound to a concrete situation; the result (which manifests itself in war or revolution) is a friend-enemy grouping, and they turn into empty and ghostlike abstractions when this situation disappears. (pp. 3031, Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political (Chicago, Chicago University Press, 1996) Schmitt adds that “the worst confusion arises when concepts such as justice and freedom are used to legitimize one’s own political ambitions.” Given that political expressions are most often wielded to resolve struggles over resources, and such struggles typically involve one party attempting to retain control over all of the resources, we may expect, as Schmitt notes, that political terms have mainly strategic uses. We have already seen that it is natural to misidentify the disequilibrium one feels upon having one’s assumptions about the social world upended with the disequilibrium one feels upon encountering a violation of justice. So Schmitt is correct to suspect that “the worst confusion” arises in the use of a term like “justice” or “fairness”. Schmitt also holds that political terms are meaningless when not used strategically. But this further assumption is not entailed by the premises about the ubiquity of strategic uses, and in any case is not required to explain Dotson’s point. Section III. “A Culture of Justification” Here are some of Dotson’s comments about the notion of a culture of justification: I take the question of how this or that paper is philosophy to betray at least one circumstance that pervades professional philosophy. It points to the prevalence of a culture of justification. Typified in the question “how is this philosophy” is a presumption of a set of commonly held, univocally relevant historical precedents that one could and should use to evaluate answers to the question. By relying upon, a presumably, commonly held set of normative, historical precedents, the question of how a given paper is philosophy betrays a value placed on performances and/or narratives of legitimation. Legitimation, here, refers to practices and processes aimed at judging whether some belief, practice, and/or 8 Camp argues that even in antagonistic contexts, there is a core of shared meaning. I criticize Camp’s claim in forthcoming work. process conforms to accepted standards and patterns, i.e. justifying norms. A culture of justification, then, on my account, takes legitimation to be the penultimate vetting process, where legitimation is but one kind of vetting process among many. within a culture of justification a high value is placed on whether a given paper, for example, includes prima facie congruence with norms of disciplinary engagement, or justifying norms, and/or can inspire a narrative that indicates its congruence with those norms for the sake of positive status. 1) manifest a value for exercises of legitimation, 2) assume the existence of commonly-held, justifying norms that are 3) univocally relevant. One can expect a high degree of uniformity of opinion about “philosophical value” in a culture of justification, and a restricted set of permissible starting points, methodologies and questions. Participants in cultures of justification fetishize policing the boundaries of the discipline by ensuring conformity with a commonly-held set of norms. When someone’s work does not so conform, granting them a scarce resource such as a tenuretrack position will seem to the participants in a culture of justification to be a violation of justice. There are signs in the discipline that there is strategic jockeying for scarce resources. The ever more pervasive splitting of disciplines into micro-fiefdoms is one such. If a discipline includes only twelve scholars, then by definition referencing their work is required for entry into that discipline. All of us have seen this process of disciplinary division occur. Its strategic nature is masked by thinking of philosophy as a science, requiring ever greater “specializations”, which in reality are just different clusterings of people working on the same question allegedly in different fields. Philosophy quite clearly manifests the symptoms of a culture of justification, and Dotson is right to hold that this is suspicious. It’s natural to think that a discipline that polices its boundaries so vigorously is one whose participants sense a constant threat of danger from the outside. Those of us with social capital are free to be unreflective about the structure of the society that grants us this capital. It is natural to expect, as Dotson also points out, members of groups that are more likely to have experienced clear instances of social injustice to be motivated to address the sources of the injustice in their academic work. There is no reason to think such work will not pay off in philosophy, as it has in other disciplines. For example, one of the main topics of recent philosophy is after all methodology. No one knows which methodologies will lead to novel insights on which topics. It is however highly likely that a diversity of methods is more likely to lead to insight than a paucity of methods. It may be that it is not directly the presence of members of underrepresented groups that is felt to be so threatening, but rather the possibility of diversity of method and subject matter of inquiry that is required to admit members of underrepresented groups into the discipline. It isn’t necessary to adjudicate between these alternative explanations of what is felt to be so threatening to see that there is a problem. Section IV. Patterns of Exclusion By assumption, the social practices that undergird philosophy’s culture of justification are implicit beliefs or (as in Haslanger) practices and habits that have no cognitive basis. As a result, they cannot be identified norms that explicitly exclude members of underrepresented groups, since that would be too obvious to ignore. These patterns of justification also did not just magically appear a decade ago. In Eileen O’Neil’s 2005 paper, “Early Modern Women Philosophers and the History of Philosophy”, she calls attention to the fact that there were many recognized and influential female philosophers in the 17th and 18th century. To explain the current sense that early modern philosophy consisted solely of men, O’Neil here as in earlier work calls attention to what she calls “the purification of philosophy”. As she writes about the now neglected female philosophers of the early modern era: The bulk of the women's writings either directly addressed such topics as faith and revelation, on the one hand, or woman's nature and her role in society, on the other. But the late eighteenth century attempted to excise philosophy motivated by religious concerns from philosophy proper. And many German historians, taking Kantianism as the culmination of early modern philosophy and as providing the project for all future philosophical inquiry, viewed treatments of “the woman question” as a precritical issue of purely anthropological interest. So, by the nineteenth century, much of the published material by women once deemed philosophical no longer seemed so. An account of the result of purification must explain not only philosophy’s culture of justification, but also its distinctive patterns of exclusion. It is difficult to deny the centrality to the history of western philosophy of two topics. One topic is social theory, philosophical reflection about the structure of society under various political or economic conditions. It is very difficult to excise social theory from, for example, Book viii of Plato’s Republic, or some of the central points of Aristotle’s Politics. The important point here is that premises about the structure of society play central roles. A second topic of great centrality to the history of philosophy is the topic of education. As Lisa Shapiro reminded me, education is the topic is at least on the face of it the topic of Plato’s Meno. More generally, education has always played a central role in responding to Plato’s arguments against democracy in The Republic. Aristotle concludes the Politics with book viii, a short treatise on education, a subject Aristotle clearly regards as central to political philosophy. Yet neither social theory nor the philosophy of education can be said to enjoy such centrality today. As a result, we find the exclusion from philosophy of much of what would be of interest to those who are concerned with systemic barriers to the full realization of their autonomy in society. It is not just members of underrepresented groups who disappear; it is major important works of great philosophers, such as Rousseau’s Emile, and in some cases, great philosophers themselves, such as John Dewey, one of the 20th century’s most influential philosophers (just not in philosophy).9 Nor is it plausible, inspecting the work that counts as pure philosophy today, that the distinction can be drawn along the lines of philosophy that is purely a priori versus philosophy that is empirical. Too much contemporary philosophy of mind, philosophy of language, epistemology, and metaphysics would fall on the impure side of the divide. The process of purification occurs unwittingly in response to structural problems created by the process of purification itself. How do we address the systematic problems facing democratic legitimacy to which Plato draws our attention in the Republic without a theory of democratic education, the topic of many of John Dewey’s essays?10 How do we prevent the formation of alliances between politicians and the wealthy that Plato argues lead to coercion of the majority of the population, who provide the bulk of society’s labor? Such problems cannot be addressed without a philosophical theory of democratic education and a philosophical account of the problems posed by the division of labor. The solution to which political philosophy has resorted is to re-conceptualize itself as the description of an ideal state, relegating the study of barriers to its realization to the discipline that Rawls, in A Theory of Justice (pp. 226-7) calls “political sociology”. One goal of John Rawls’s 1993 book, Political Liberalism (New York: Columbia University Press) is to make political philosophy an autonomous discipline. But Rawls admits that the possibility of the realization of an ideal state is a constraint on the ideals themselves. It seems plausible to suppose that the autonomy of political philosophy is not just intended to be autonomy from moral philosophy, but also autonomy from “political sociology”. Since Rawls himself excludes the study of the possibility of the realization of an ideal state from the discipline of political philosophy, Rawls’s project could hardly be thought of as a success. It is also not possible to extrude from philosophy the study of the nature of a just state. Philosophy without this question at its center has no clear continuity with its own acknowledged canon. The process of purification ends up necessarily removing premises from the philosophical arguments, leaving but a skeleton of a discipline behind. If the story Dotson and O’Neill tell is anything close to correct, the solution required is a de-purification of philosophy. And this is exactly Dotson’s prescription, which I conclude by repeating: . (1) Value placed on seeking issues and circumstances pertinent to our living, where one maintains a healthy appreciation for the differing issues that will emerge as pertinent among different populations and . (2) Recognition and encouragement of multiple canons and multiple ways of 9 Thanks to Lisa Shapiro for discussion. E.g. the essays in John Dewey, Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education (New York: Macmillan Press, 1916). 10 understanding disciplinary validation.