Great-Teaching-As-Conducting-1 - Maru-a

advertisement

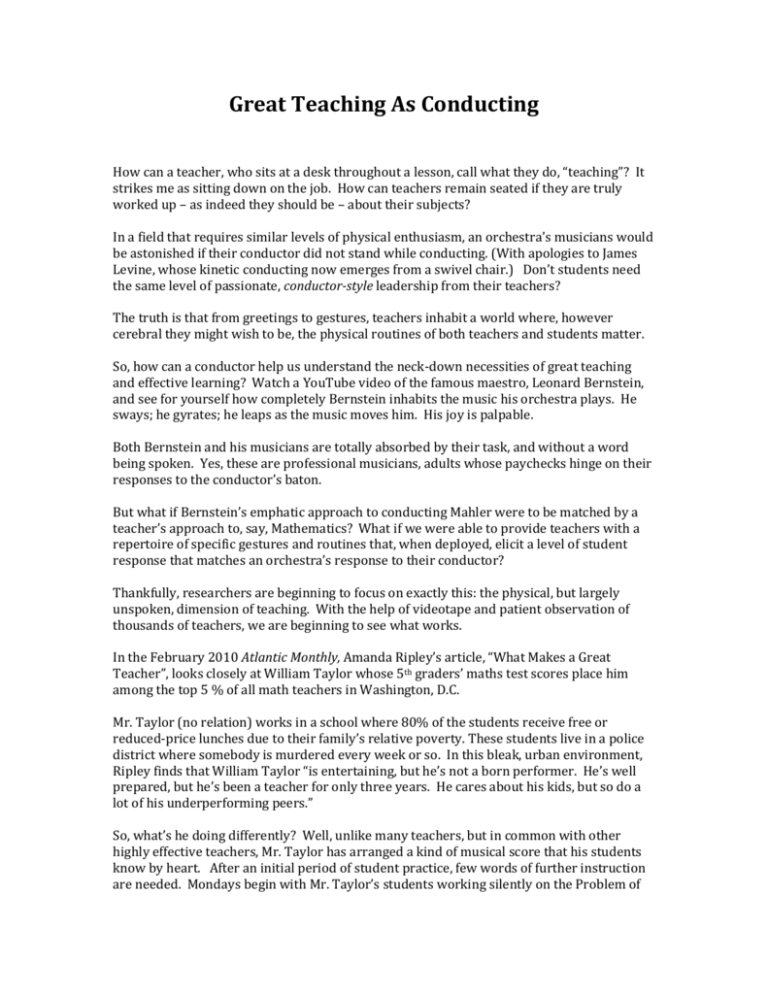

Great Teaching As Conducting How can a teacher, who sits at a desk throughout a lesson, call what they do, “teaching”? It strikes me as sitting down on the job. How can teachers remain seated if they are truly worked up – as indeed they should be – about their subjects? In a field that requires similar levels of physical enthusiasm, an orchestra’s musicians would be astonished if their conductor did not stand while conducting. (With apologies to James Levine, whose kinetic conducting now emerges from a swivel chair.) Don’t students need the same level of passionate, conductor-style leadership from their teachers? The truth is that from greetings to gestures, teachers inhabit a world where, however cerebral they might wish to be, the physical routines of both teachers and students matter. So, how can a conductor help us understand the neck-down necessities of great teaching and effective learning? Watch a YouTube video of the famous maestro, Leonard Bernstein, and see for yourself how completely Bernstein inhabits the music his orchestra plays. He sways; he gyrates; he leaps as the music moves him. His joy is palpable. Both Bernstein and his musicians are totally absorbed by their task, and without a word being spoken. Yes, these are professional musicians, adults whose paychecks hinge on their responses to the conductor’s baton. But what if Bernstein’s emphatic approach to conducting Mahler were to be matched by a teacher’s approach to, say, Mathematics? What if we were able to provide teachers with a repertoire of specific gestures and routines that, when deployed, elicit a level of student response that matches an orchestra’s response to their conductor? Thankfully, researchers are beginning to focus on exactly this: the physical, but largely unspoken, dimension of teaching. With the help of videotape and patient observation of thousands of teachers, we are beginning to see what works. In the February 2010 Atlantic Monthly, Amanda Ripley’s article, “What Makes a Great Teacher”, looks closely at William Taylor whose 5th graders’ maths test scores place him among the top 5 % of all math teachers in Washington, D.C. Mr. Taylor (no relation) works in a school where 80% of the students receive free or reduced-price lunches due to their family’s relative poverty. These students live in a police district where somebody is murdered every week or so. In this bleak, urban environment, Ripley finds that William Taylor “is entertaining, but he’s not a born performer. He’s well prepared, but he’s been a teacher for only three years. He cares about his kids, but so do a lot of his underperforming peers.” So, what’s he doing differently? Well, unlike many teachers, but in common with other highly effective teachers, Mr. Taylor has arranged a kind of musical score that his students know by heart. After an initial period of student practice, few words of further instruction are needed. Mondays begin with Mr. Taylor’s students working silently on the Problem of the Day written on the blackboard. On the front wall, Mr. Taylor has posted time-saving hand signals: for the bathroom, you raise a closed hand; to ask or answer a question you raise an open hand. If you’re having a terrible day, and cannot bear to participate, you are supposed to signal this fact by putting your head down on your desk. No student has done so in three years. When Mr. Taylor calls on his students to help solve a Maths problem, he does so in a particular way. He poses the question and, while every student is pondering the correct response, he dips into a can of clothespins – what he calls his “equity sticks” – each of which has a student’s name on it. By drawing out a randomly-chosen clothespin he ensures that reluctant responders are not ignored. From the intensity of Multiplication Bingo – “one girl is literally shaking with excitement” – to the no-pencil rigours of Mental Math, where students thrust orange index cards up in the air, Mr. Taylor has designed routines and quick transitions between activities that save enormous amounts of time. There is a tempo and a rhythm to all this, a brisk sequencing that any conductor would be thrilled to witness. One of Leonard Bernstein’s veterans said, "When he gets up on the podium, he makes me remember why I wanted to become a musician." When Mr. Taylor conducts a Maths class, I bet more than a few of his students think of becoming mathematicians. Or teachers. As you might expect, Mr. Taylor has little use for his desk, except as a place to sit and recover – but only when class is over. (Teachers wishing to learn more would do well to go online and read the 7 March, 2010, New York Times Magazine article by Elizabeth Green, “Building A Better Teacher”, featuring the work of a maestro of the classroom, Doug Lemov.) Andrew Taylor is the Principal of the Maru-a-Pula School in Gaborone, Botswana. His email address is: principal.map@gmail.com. Maru-a-Pula’s website is: www.maruapula.org