MA Medieval Studies 2014/15

advertisement

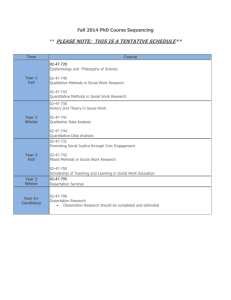

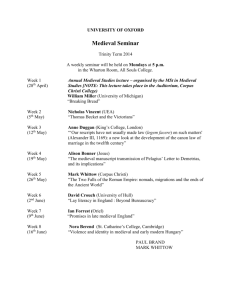

MA in Medieval Studies 2014-15 Departments of History and English, with the Departments of Drama & Theatre Studies, French, Italian, Music, and The Museum of London Medieval MA Programme Timetable 22 September 2014 Autumn Term begins: Welcome Week 23 September 2014 Welcome Party 5.00pm 10 December 2014 Progress Review with Programme Directors 12 December 2014 Autumn Term ends 12 January 2015 Spring Term begins 13 January 2015 Submission date for drafts of assessed work from Option Courses taught in Autumn Term (hand in by 3pm to History Postgraduate Office) 25 March 2015 Progress Review with Programme Directors 27 March 2015 Spring Term ends 27 April 2015 Summer Term (including Examinations for Skills Courses) begins 30 April 2015 Submission date for drafts of assessed work from Option Courses taught in Spring Term and Museum Skills (submit to course leaders) 4 June 2015 Final submission date for assessed work from Programme and Option Courses and Museum Skills (hand in by 3pm in History Postgraduate Office and submit electronically to TurnItIn) 10 June 2015 Dissertation Symposium 12 June 2015 Summer Term ends End of June 2015 Schedules of dissertation work to be agreed with supervisors Mid-Summer 2015 Progress Review (date to be confirmed) 4 September 2015 Submission date for Dissertations (hand in by 3pm to History Postgraduate Office and submit electronically to TurnItIn) Table of Contents Introduction 1 Keeping in Touch 2 About the Degree 3 Course Descriptions 9 The Dissertation 14 Medievalists at Royal Holloway 18 Appendix 1: Marking Criteria 19 Appendix 2: Marking Criteria for Oral Presentations 21 Introduction: Welcome to Royal Holloway Royal Holloway, University of London was formed by the merger in 1985 of two independent Colleges of London University, both initially women’s colleges: Bedford College, founded in 1849, and Royal Holloway, founded in 1886. The campus is located on Royal Holloway’s wooded 100-acre site at Egham Hill in Surrey, in an area rich in historic interest. Windsor Castle and Windsor Great Park are very close at hand. Nearby, at St George’s Hill Surrey, the Diggers set up the world’s first agrarian commune in 1649. Below Egham Hill stretches the Thameside meadow of Runnymede where the barons in 1215 forced King John to seal Magna Carta. The campus is dominated by the magnificent Victorian Founder’s Building, which contains the Picture Gallery and its famous collection of Victorian art. There is also a growing range of modern buildings, including a library, halls of residence, Students’ Union building, and the new Windsor Building. These resources are used by Royal Holloway’s 7,000 students, who are comprised of equal numbers of men and women and derive from more than 120 countries all over the world. Egham is situated on the A30, 19 miles from central London. It is 2 miles from the M25 (junction 13) and 6 miles from Heathrow International Airport. Fast trains travel regularly from Egham to London Waterloo in 35 minutes. Royal Holloway has a second site at 11 Bedford Square, London WC1, adjacent to the British Museum and the Senate House of the University of London. Some parts of the MA may be taught here. Students automatically qualify for membership of the Institute of Historical Research (located in the Senate House) and are encouraged to take an active part in the research seminars held there. Students are also encouraged to participate in the activities organised by the Institute of English Studies, also in Senate House, particularly the meetings of the London Old and Middle English Research Seminar. The Medieval MA This multidisciplinary MA has been running successfully for almost thirty years and has gained a high international reputation. It makes full use of the historical and scholarly environment of London. The aim of the Medieval Studies degree is to introduce students to many different aspects of medieval society and culture while allowing them to concentrate on particular areas of interest. The degree emphasises the skills that research students need, whether their focus is literary or historical, and provides an introduction to a wide range of source materials, such as artefacts, archives, manuscripts, and printed sources. Students are encouraged to combine a Programme in one discipline, literary or historical, with at least one option or skill in another. Students are thoroughly prepared for the dissertation that completes the course and they can, if they wish, develop their MA work into convincing proposals for further research at doctoral level. The MA is enhanced with the resources of the Museum of London and the research skills of its staff. Students may be able to follow courses taught at the Museum of London and to acquire specialist skills relating to the display and interpretation of the material culture of the medieval world. There is also the possibility of holding a summer internship there. 1 Keeping in Touch Please ensure that we have up-to-date contact details for you throughout your degree, including your postal address, phone number, and e-mail address. Please learn how to use the College e-mail address that will be allocated to you, even if you have messages forwarded from it to a private e-mail address (contact the Computing Centre for details). Usually we will try to reach you first via e-mail, so ensure that you check your college e-mail regularly. It is important that we can contact you quickly. If you move or change your phone number, please update your details through the Student Portal. History Department Office 01784 443314 Postgraduate Administrator: Mrs Marie-Christine Ockenden (Tues-Fri only) 01784 443311 m.ockenden@rhul.ac.uk English Department Office 01784 443215 Postgraduate Administrator: Mrs Lisa Dacunha 01784 443215 lisa.dacunha@rhul.ac.uk@rhul.ac.uk If you have a Problem... Whatever the problem—financial, academic, health, domestic—talk to someone about it as soon as possible. Please do not suffer in silence: many problems can be tackled successfully, and two heads really are often better than one. It would be best to talk in the first instance to one of the Programme Directors, who are, formally, the Personal Advisers for all students on the degree programme: Professor Peregrine Horden Dr Jenny Neville 01784 443400 01784 414115 p.horden@rhul.ac.uk j.neville@rhul.ac.uk If it is not appropriate to talk to a Programme Director, then consult Professor Jonathan Phillips, Head of the History Department (01784 443295; j.p.phillips@rhul.ac.uk), or Professor Tim Armstrong, Head of the English Department (01784 443747; t.armstrong@rhul.ac.uk), or Professor Katie Normington, Dean of Arts and Social Sciences (01784 443928; k.normington@rhul.ac.uk). If you have matters to raise concerning departmental or College policies you can talk to the postgraduate representative on either the History or English Department Postgraduate Student-Staff Committee or to the chair of the Student Union Postgraduate Committee. The former can be reached via the relevant Departmental Office; the latter can be contacted through the Student Union Welfare Office. Counselling: On personal matters you may like to talk to someone at the College Counselling Service: www.rhul.ac.uk/studentlife/supporthealthandwelfare/studentcounselling.aspx email: counselling@rhul.ac.uk 01784 443128. You may also choose to talk to the College Chaplains: http://www.rhul.ac.uk/ecampus/campuslife/thechapel.aspx email: chaplaincy@rhul.ac.uk 01784 443950. On practical matters relating to fees, accommodation, regulations, or other formal aspects of your life at Royal Holloway, you can consult the Registry: http://www.rhul.ac.uk/ecampus/academicsupport/home.aspx. 2 About the Degree Aims: to promote a multidisciplinary understanding of the Middle Ages. to provide the skills and knowledge necessary for the study of the Middle Ages, whether for further research or for personal intellectual development. to provide advanced study of specialised topics within Medieval Studies. to expand and enhance the intellectual community devoted to the study of the Middle Ages. Learning Outcomes: Students who successfully complete this degree will: know how to find, organise, deploy and assess the primary and secondary sources of their research. be able to apply specific skills relevant to the study of the Middle Ages. comprehend a wide variety of materials and approaches related to the Middle Ages. be able to analyse, assess and formulate arguments related to specific medieval topics. be able to conduct independent research. Workload If you are following a post-graduate taught degree, you can expect to put in 1,800 ‘notional learning hours’. This includes your own private study as well as contact time with your tutors and examinations. If you are following the degree full-time, over fifty weeks this averages out at thirty-six hours per week. Of course, you may work more in some weeks than in others. If you follow the degree part time (over two years), you can expect to put in 900 learning hours per year—about eighteen hours per week. As you will discover, most of these hours will be taken up with private study, so you can tailor your workload to suit your own study habits and other commitments. For example, if you are following the degree full-time, you will probably have six and half hours of contact time per week. You will, however, have preparation and research to do in your own time. Attendance Please remember that attendance at all classes or seminars is compulsory. Non-attendance, other than in documented extenuating circumstances, may result in the termination of your registration. Coursework and Drafts You may be asked to give oral presentations, submit drafts of essays, or carry out other exercises during courses on the degree. Even if this work is not assessed and thus does not count toward a final mark, it is an essential component of the course, and you may be issued with a Formal Warning if you do not complete it. 3 About the Degree Structure of the Degree The degree is composed of 180 credits. The weighting of each element of the degree is indicated below: Option 2 20 credits Option 1 Dissertation 20 credits 60 credits Skill Course 20 credits RDC 20 credits Programme Course 40 credits Full-Time Study A full-time student will complete all the above elements in one academic year (fifty weeks). The schedule normally follows this pattern: Autumn Term: Programme Course (2 hours per week) First Option Course (2 h/wk) Research Development Course (1½ h/wk) Skills Course (average of 1 h/wk)* Spring Term: Programme Course, continued (2 h/wk) Second Option Course (2 h/wk) Research Development Course, continued (1½ h/wk) Skills Course, continued (1 h/wk) Summer Term: Examination for Skills Course (if applicable) Dissertation (May to September) * The number of hours per week varies; some Skills courses take place over one term instead of two and so meet for two hours per week 4 About the Degree Part-Time Study Part-Time Students complete the same elements over two years (102 weeks). They usually take the courses as follows: Year one: Programme Course Research Development Course Year two: Option Course Option Course Skills Course Dissertation Assessment What follows is a brief summary of the main regulations for this MA programme. For full regulations pertaining to Assessment, please see the PGT Student Handbooks produced by the Departments of History and English. PLEASE NOTE: Other than work written during a formal examination, all assessed work (essays, assignments, etc) must be submitted in hard copy ANONYMOUSLY and in DUPLICATE. An identical version must also be submitted electronically to TurnItIn. All assessed work must be accompanied by the official coversheet and Declaration of Academic Integrity. Be sure to write your candidate number accurately on the coversheet. You must include your word-count at the end. Submission by email is not acceptable. The Research Development Course is assessed continuously (i.e. throughout the running of the course, not after its completion) as follows: First Essay (50%), Second Essay (50%). Programme Courses are assessed by two essays of 4,500 – 5,000 words, for a total of 9,000-10,000 words (including footnotes but excluding bibliography). The course teacher will inform you about the selection of topics. Deadlines for the submission of drafts and final versions of these essays can be found on the inside cover of this Handbook. Option Courses are assessed by one essay of 4,500 – 5,000 words (including footnotes but excluding bibliography). The course teacher will inform you about the selection of topics. Deadlines for the submission of drafts and final versions of essays can be found on the inside cover of this Handbook. The Skills Courses are assessed by examinations which take place during the Summer Term (in May), with the exception of the Museum Skills course, which is assessed in the same way as the Option Courses (see above). All MA work is to be presented word-processed, in a clear, scholarly form, and must conform to postgraduate standards. Drafts do not need to be submitted anonymously and do not require coversheets. 5 About the Degree The Marking Scheme All work which contributes to the award of the MA degree is assessed by two internal examiners; it may also be read by an external examiner. The Examination Sub-Board (which meets in October or November) considers all the marks. All four elements of the MA degree (Programme Course, Option Courses, Skills Courses, Dissertation) carry equal weight. The marking scheme is as follows: 70-100% 60-69% 50-60% 0-49% Distinction Merit Pass Fail Please see Appendix 1: Marking Criteria for further details of the marking scheme. To be awarded the degree a student must achieve a mark of at least 50% in each course. Failure marks of between 40 to 49% may, at the discretion of the Examining Board, be condoned in one or more courses constituting up to a maximum of 40 credits, but the Dissertation and the Programme Course must be passed with a mark of 50% or more. A student who does not pass a course at the first attempt may be allowed to re-sit on one occasion, according to the discretion of the Examination Board. This attempt must take place at the next available opportunity—that is, in the following year at the same time as the original examination. To be awarded a Merit a student must achieve a weighted* average of at least 60% over all courses, with no mark falling below 50%, and normally with a mark of at least 60% in the dissertation. A Merit cannot be awarded if a student re-sits or re-takes any element of the Programme. To be awarded a Distinction a student must achieve a weighted* average of at least 70% over all courses, with no mark falling below 60%, and normally with a mark of at least 70% in the dissertation. A Distinction cannot be awarded if a student re-sits or re-takes any element of the Programme. Penalties for Over-length Work All over-length work will be penalised as follows: for work which exceeds the upper word limit by at least 10% and by less than 20%, the mark will be reduced by ten percentage marks, subject to a minimum mark of a minimum pass. for work which exceeds the upper word limit by 20% or more, the maximum mark will be zero. An accurate word-count should be included at the end of each essay. Note that this count should include footnotes but exclude bibliographies. Under-length Work is not penalised as such. You should normally aim to produce assessed work that is no more than 100 to 200 words under the stipulated maximum. But what matters is the quality of your argument, and concision is almost always a virtue. Do not artificially inflate your writing simply to achieve a higher word count. That is, the average must take into account the fact that a 40-credit course counts for twice as much as 20-credit course. * 6 About the Degree Lateness All your assessed essays and your dissertation must be submitted by the deadlines specified on the inside cover of this booklet. Be sure that you are aware of these dates and have made a note of them. All unauthorised late submissions will be penalised as follows: for work submitted up to 24 hours late, the mark will be reduced by ten percentage marks, subject to a minimum mark of a minimum pass. for work submitted more than 24 hours late, the mark will be zero, although it will still be eligible to count for the purposes of course completion. Extensions Extensions to deadlines for assessed work must be negotiated in writing, in advance, with a Programme Director; it is not sufficient merely to inform a course instructor, as he or she does not have the authority to agree to late submission. Extensions to deadlines will be granted only under exceptional circumstances (see below) and, where appropriate, on the submission of satisfactory supporting documentary evidence. If students encounter problems during the programme that necessitate suspension of studies or a switch from full-time to part-time study, such changes should be approved by the end of the Spring Term. Proposed changes must be discussed with a Programme Director before any administrative action is taken. Advice on the procedure is available from the Departmental Administrators of both departments. Please note that College accommodation needs to be vacated at the end of the 50-week term; i.e. very near the date for submission of the dissertation. You should check the date by which you need to leave with the Accommodation Office in advance, and be prepared to make any necessary arrangements. It is particularly important to make these enquiries if there are extenuating circumstances that might necessitate an extension to the deadline for the dissertation. Illness and Extenuating Circumstances If illness or other extenuating circumstances are disrupting your work, please contact a Programme Director as soon as possible. If your condition seems likely to detract from, or delay submission of, any assignments, you should obtain medical evidence (if possible) and document as precisely as possible when and how your condition has affected you. Please consult the College’s ‘Instructions to Candidates’ if you believe that illness or other extenuating circumstances have adversely affected your assessed work. These instructions can be found at: http://www.rhul.ac.uk/ecampus/academicsupport/examinations/examinations/home.aspx Requests for special consideration of circumstances affecting assessed work must be received by the Programme Directors by 31 August 2015. Results Students can find out whether they have gained a Distinction, Merit, Pass, or Fail after the meeting of the College MA Board, which takes place at the end of the candidate’s course (usually in October or November). Detailed results will then be sent by the Registry in the post (please ensure that the Registry has your up-to-date address). The Graduation ceremony takes place in December. Small prizes are awarded to the students gaining the highest distinctions in History and English courses respectively. 7 About the Degree Feedback Feedback on student performance during the course (formative assessment) is provided through course tutors’ comments on drafts of assessed work and through interviews with the Programme Directors. Plagiarism Plagiarism, the presentation of other people’s work as if it were your own, is a very serious issue. Please ensure that you understand fully what plagiarism and its penalties are. More detailed discussion of it can be found in the booklet for the Research Development Course. The Research Development Course will address the methods whereby you acknowledge your sources in detail, but please ask one of your course teachers if you are in any doubt about your practice. Duplication You should be careful not to duplicate source material or arguments used for one essay in another essay or other assessed work. Ideally, you will use the assessed essays and dissertation to demonstrate your intellectual range. Repeated material may be awarded a mark of 0%. If you are in any doubt, please consult your course teachers before you submit your essays. More Information Available Online For an overview of the programme, see: http://www.rhul.ac.uk/english/coursefinder/mamedievalstudies.aspx For the programme’s website, see: http://www.rhul.ac.uk/english/informationforprospectivestudents/postgraduatetaught/ mamedievalstudies.aspx 8 Medieval MA Course Descriptions The Research Development Course (RDC) (HS5217) Dr Jenny Neville and Professor Peregrine Horden (along with other instructors on the degree) Taught at Royal Holloway, on Wednesdays 1 - 2.30 pm. Term 1: Arts Buiding, First Floor, Room F-001. Term 2: Windsor Building, First Floor, Room 1-02. This is a mandatory course taken by all students pursuing the Medieval MA. It has four main aims. 1. This course makes students aware of issues and topics associated with the study of the Middle Ages on a wide and interdisciplinary basis. It especially seeks to counteract the traditional distinctions between literary and historical approaches. Staff members from all the departments and institutions involved in the Medieval MA will lead discussions based on their research so as to demonstrate the range of approaches and issues currently under investigation in the field of Medieval Studies. 2. This course trains students in the skills needed to undertake research in the field of Medieval Studies. These skills will vary from year to year (depending, for example, on the availability of staff members), but they will normally include the following types of activity: referencing techniques (footnotes and bibliography), reviewing, finding and dealing with primary sources, and reading non-textual sources. There will also be a session on preparing a dissertation. 3. This course provides opportunities for students to engage in and practice academic discourse. Students will have the opportunity to present their ideas to their peers with the advantage of instruction and example, in an atmosphere of mutual support. A significant proportion of the meetings will be devoted to student presentations, with students in charge of leading and managing discussion (‘chairing’). Students are also expected to respond to each other’s presentations. 4. This course provides a venue in which the MA cohort as a whole may form an intellectual community. Students who might otherwise never meet will have an opportunity to interact with each other and hear the ideas and opinions of those taking different courses from their own. The course is assessed throughout the course, with grades assigned for two essays, one in the Autumn and one in the Spring term. The final grade for the course will be made up from the combined average of both assignments. The Programme Courses Medieval London (HS5200) Dr Clive Burgess To be taught in Royal Holloway, Egham, on Wednesdays 10-12 over two terms, in McCrae 333. Despite the onslaught of the plague in the mid fourteenth century, London remained by far the largest, the most populous and the wealthiest city in England. Its population may have been sustained by constant immigration, but its institutions had developed in a manner that sustained and consolidated its distinctive character and, in the fifteenth century, the city went on to flourish commercially and increasingly dominated the English economy. In many respects, London has never faltered since. This course, then, analyses London at a particularly formative time. It looks at the way in which it was governed, at the ways in which it organised the behaviour of its citizens and at the developments in its commercial life in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. It attempts, too, to integrate the City’s religious life into an understanding of its broader social fabric, and as an integral part of this will consider both educational provision and the access that Londoners had to books. The course also asks what it was like to live in medieval London - how clean were its streets, how did its citizens feed 9 Courses themselves and how did they entertain themselves? As well as considering heresy and revolt within the city in the later fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the course will also devote attention to the important questions of the contribution made both by women and by young people to the economic and social life of England’s capital city. Students will work from a variety of historical texts for each session, and will make class presentations two or three times a term. A detailed reading list will be provided. Most books are available in the Royal Holloway library (Egham campus) and in London at the Senate House Library, the Institute of Historical Research and the Guildhall Library. Introductory reading: Barron, Caroline M., London in the Later Middle Ages (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004) Strohm, P., Social Chaucer (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989) Thrupp, Sylvia, The Merchant Class of Medieval London, 1300-1500 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1962) Wallace, D., ed., The Cambridge History of Medieval English Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999) Medieval Narratives (EN5607) Dr Alistair Bennett, with Dr Catherine Nall, Dr Pirkko Koppinen, Professor Ruth Harvey, and Dr Stefano Jossa To be taught in the International Building at Royal Holloway, Egham, on Wednesdays 10-12, over two terms. This course explores the traditions and forms of medieval story-telling. In addition to texts in Old and Middle English, the course will include key French texts in translation. We will explore various narrative genres, such as epic, chronicle, romance, and fabliau, and one of the major tale collections of the period, the Canterbury Tales. The aim of this course is to broaden your knowledge of the range of medieval narratives and to provide you with relevant theoretical approaches so that you can develop the types of analyses that you perform on them. Introductory Reading: Davenport, W. A., Medieval Narrative: An Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004). [a good book to buy] Ong, W., Orality and Literacy (London: Routledge, 1982) Chaytor, H., From Script to Print (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press,1945) Vitz, E. B., Medieval Narrative and Modern Narratology: Subjects and Objects of Desire (New York: New York University Press, 1989) Wallace, David, ed., The Cambridge History of Medieval English Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999) Option Courses Term 1 EN5611 Literature of Medieval London Dr Alastair Bennett To be taught in the English Department in term 1, on Wednesdays 3-5 pm, in IN208. The course invites students to read and discuss a wide range of late medieval texts in relation to the city of London. It interrogates the way that London, its inhabitants and its institutions are represented in medieval literature, from the court at Westminster to the pulpit at St Paul’s, the ‘lewed ermytes’ of Cornhill and the inns of Southwark. It considers London as a site of literary composition, home to poets including Langland, Gower and Chaucer, and as a locus of textual production, where many important literary manuscripts were copied and circulated. And it also offers opportunities to think about other medieval cities, real and imagined, in their relation to London. How and why did medieval writers imagine London as a ‘new Troy’, and how did the realities of this earthly city inform their thinking about the heavenly city, New Jerusalem? The reading for this course includes some of the 10 Courses very best late medieval literature and a number of rich and interesting lesser-known texts. Students will read selections from Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde and The Canterbury Tales, Langland’s Piers Plowman, Gower’s Vox Clamantis and Confessio Amantis, Hoccleve’s Complaint and Dialogue and Lydgate’s Siege of Thebes, amongst others. We will read Middle English texts in glossed editions, and Latin texts in modern English translations. Introductory Reading: Barron, Caroline, London in the Later Middle Ages: Government and People, 1200-1500 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004) Hanna, Ralph, London Literature, 1300-1380 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005) Hsy, Jonathan, ‘City’, in A Handbook of Middle English Studies, ed. by Marion Turner (Oxford: WileyBlackwell, 2013), pp. 315-29 Lindenbaum, Sheila, ‘London texts and Literate Practice’, in The Cambridge History of Medieval English Literature, ed. by David Wallace (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), pp. 284309 Mooney, Linne R, and Estelle Stubbs, Scribes and the City: London Guildhall Clerks and the Dissemination of Middle English Literature, 1375-1425 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2013) Turner, Marion, Chaucerian Conflict: Languages of Antagonism in Late Fourteenth-century London (Oxford: Clarendon, 2007) Byzantium and the First Crusade (HS5219) Professor Jonathan Harris Term 1. To be taught at Royal Holloway, Egham. Date and time to be confirmed. This course traces the response of the rulers of the Byzantine Empire to the First Crusade and to the establishment of the Latin East. Early classes will focus on the background of the empire as it was in the middle of the eleventh century, its relations with the Latin West and the accession and reign of Alexios I Komnenos (1081-1118). We shall then turn to the lead-up to and events of the crusade. A range of Byzantine and Western source materials will be examined in translation in an attempt to determine how the Byzantines viewed the crusaders, what they considered their aims to be, what policies they adopted towards them, and—perhaps most important of all—what mistakes they made in dealing with this unprecedented phenomenon. Introductory Reading: Angold, Michael, The Byzantine Empire, 1025-1204: A Political History, 2nd edn (London: Longman, 1997) Harris, Jonathan, Byzantium and the Crusades (London: Hambledon, 2003) Phillips, Jonathan, Holy Warriors: A Modern History of the Crusades (London: Bodley Head, 2009) The Court in England and Europe, c.1350-c.1450 (HS5235) Professor Nigel Saul Term 1. To be taught at Royal Holloway, Egham, on Wednesdays, 2.30-4.30, in McCrae 322. The main aim of the course is to examine comparatively the development of princely courts in late medieval Europe, with particular reference to the social and governmental functions of the court, the role and composition of the courtiers, the imagery and propaganda of the court, and the popular responses to it. The course will look at court history from a comparative perspective, examining developments in England alongside those on the continent. Particular attention will be given to the following topics: the social and governmental functions of the court, the role and composition of the courtiers, the imagery and propaganda of the court, and the popular responses to it. The principal courts to be studied will be those of England and France, although evidence from Burgundy and the German Empire will be considered, too. Introductory Reading: Starkey, David, ed., The English Court from the Wars of the Roses to the Civil War (London: Longman, 1987) 11 Courses Term 2 Arthurian Literature and Tradition in England (EN5604) Dr Catherine Nall Term 2. To be taught at Royal Holloway, Egham. Date and time to be confirmed. This course will centre on a study of Arthurian literature in England from Geoffrey of Monmouth to Malory’s Morte d’Arthur. It involves comparative study of texts across three centuries and at least two languages (foreign language texts may be read in translation) and examines the critical issues raised by intertextuality and the literary treatment of myth and legend. We will also investigate non-literary material (chronicles, art, political events) in order to relate developments in Arthurian literature to the changing political and cultural context. Introductory Reading: Vinaver, Eugene, ed., Malory: Complete Works (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971) [or later editions] Barron, W. R. J., ed., The Arthur of the English (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2001) Burgess, Glyn S. and Karen Pratt, eds., The Arthur of the French: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval French and Occitan Literature (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2009) Archibald, Elizabeth and Ad Putter, eds., The Cambridge Companion to the Arthurian Legend (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009) Byzantium and the Fourth Crusade (HS5220) Professor Jonathan Harris To be taught at Royal Holloway, Egham. Date and time to be confirmed. This course takes a long term view of the crusade which captured and sacked Constantinople, the capital city of the Byzantine empire, in April 1204. Starting in 1180, it places events in the context of relations between the Byzantines and previous crusades and assesses how key developments such as the usurpation of Andronicus I, the Third Crusade and the empire’s internal weakness contributed to the ultimate outcome. We shall then turn to the events of 1198-1204. Translations of accounts left by contemporaries and eyewitnesses (both Byzantine and Western) will be studied in detail as we try to discover why an expedition that set out with the intention of recovering Jerusalem from Islam ended up pillaging the greatest city in the Christian world. Introductory Reading: Angold, Michael, The Byzantine Empire, 1025-1204: A Political History, 2nd edn (London: Longman, 1997) Harris, Jonathan, Byzantium and the Crusades (London: Hambledon, 2003) Phillips, Jonathan, The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople (London: Cape, 2004) The English Reformation and its Medieval Background (HS5306) Dr Clive Burgess To be taught at Royal Holloway, Egham in term 2 on Wednesdays, 4-6pm.. This course will make a concerted effort to look at, and evaluate, the Reformation paying as much regard to what was going on before as what emerged in the long-term – ordinarily the longer-term perspective has proved far more dominant, to the detriment of a balanced perspective. Having briefly considered what was done in the 1530s and 1540s, the course will attempt to put these turbulent decades into their own long-term context by outlining the social and political conditions of the fifteenth century. Appropriate attention will be paid to the ‘major’ players of pre-Reformation institutional religion, looking in particular at the role of the monasteries and colleges, and also at parish religion. Individuals, both orthodox and heretical, will be studied, again to derive a better sense of context for the changes that were to come in the sixteenth century. Having prepared the ground, events such as the monastic and collegiate dissolutions, the Pilgrimage of Grace, and the mid Tudor rebellions will be appraised as part of an attempt to gauge the tenor of society in the mid and later sixteenth century, and the part that the Reformation had played in defining the prevailing atmosphere. 12 Courses Introductory Reading: Swanson, R., Church and Society in late Medieval England (Oxford: Blackwell, 1989) Duffy, E., The Stripping of the Altars, 2nd edn (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005) Haigh, C., English Reformations (Oxford: Clarendon, 1993) Heath, P., Church and Realm (London: Fontana, 1988) Rex, R., The Lollards (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2002) Glasscoe, Marion, English Medieval Mystics: Games of Faith (London: Longman, 1993) Clark, J., ed., The Religious Orders in Pre-Reformation England (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2002) Skills Courses Latin for Medievalists (HS5250) Dr Hannes Kleineke Terms 1 & 2. To be taught at Royal Holloway. Day and time to be arranged. The aim of the course is to enable students to learn enough Latin to be able to use it for research purposes, especially if they are going on to doctoral work following the MA. Students will be strongly recommended to take a summer follow-up course in Latin to confirm what they have learnt. By the end of the course students will be able to: Read simple texts in classical Latin at a level approaching that of GCSE Parse all five declensions and indicative verbs Read and understand documents in basic medieval Latin such as wills, deeds and accounts Assessment: by written examination (3 hours), including a translation of medieval material, as well as a comprehension test; use of dictionaries is allowed. Suggested Reading: Hendricks, Rhoda A., Latin Made Simple (London: Heinemann, 1982) Cheney, C. R., ed., A Handbook of Dates for Students of British History, Royal Historical Society Guides and Handbooks 4, new edn. rev. by Michael Jones (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000) Stuart, Denis, Latin for Local and Family Historians: A Beginner’s Guide (Chichester: Phillimore, 2000) Gooder, Eileen A., Latin for Local History: An Introduction, 2nd edn (London: Longman, 1978) Museum Skills (HS5237) Term 2. Taught at the Museum of London over one term. Mondays 2.30-4.30. This course aims to promote an appreciation and critical understanding of the history and nature of the museum sector in Britain. Taught at the Museum of London, it will use this institution as an example to explore the nature of museum collections, how these are acquired and cared for, and how museums go about using these collections to communicate to a range of different audiences. Using archaeological and early social history collections it also aims to encourage and improve the use of museum resources for research. Students will learn how museum collections are cared for, catalogued and used, and how exhibitions and other museum projects are organised. Introductory Reading: Kavanagh, Gaynor, ed., Museum Provision and Professionalism (London: Routledge, 1994) Merriman, Nick, ed., Making Early Histories in Museums (London: Leicester University Press, 1999) Assessment: one essay of 5,000 words or an appropriate exercise at the tutor’s discretion. 13 The Dissertation (HS5218 or EN5610) The dissertation is an independent research project, which results in a piece of original work of 12,000 – 15,000 words. It is usually researched and written in the months following the completion of the other courses on the programme (i.e. from June to September). Part-time students normally complete the dissertation in the second year of their programme, although they are strongly advised to arrange a supervisor and begin their research during their first Summer Term. Getting Started It can be daunting to begin such a large project, so we have a session in March, as part of the RDC, to help you to begin thinking about your dissertation and to offer advice. In addition, at the beginning of June we ask you to prepare an abstract of your proposed topic, a preliminary bibliography, and an oral presentation explaining your intended research. The marks for these assignments will contribute to the final grade of your dissertation as follows: Abstract Preliminary Bibliography Oral Presentation 5% 5% 15% The main dissertation itself will contribute the remaining 75% of the final mark for this component of your degree. More information about these components can be found below. Suggested Dissertation Schedule By mid May By early June Early in June By 1 July By mid August Early September All students should have had initial consultations with supervisors and settled upon a provisional title. Students should have seen their supervisors to discuss a detailed plan of chapters and receive advice on the writing of the first draft. All students will submit their abstracts and bibliographies; the RDC Dissertation Symposium will take place. See inside front cover for date. Supervisors should have received a final title plus the detailed plan of chapters in writing. Students and supervisors should have arranged a timetable for: a) receiving and returning the first draft; and b) supervisions during the summer vacation. Students should have submitted any drafts for comment to their supervisors. Note that a rough or incomplete draft early in the summer is more useful to you than a more polished effort at the last minute. Submission deadline 14 The Dissertation The Abstract (5%) The abstract should be no more than 500 words. It should set out the research question that you intend to answer with your dissertation, briefly situate it in the context of previous scholarship, indicate what kind of methodology you intend to adopt, and suggest the likely implications of your research. That is, you may not yet know what the answer to your research question will be, but you should be able to suggest how you will find that answer, what kind of answer it will be, and what significance it might have. References to previous scholarship must be properly referenced according to the MHRA Style Guide. Credit will be given for: the originality and suitability of the research question knowledge and presentation of the scholarly context the clarity and appropriateness of the methodology to the chosen topic clear exposition of the implications of your research good, scholarly writing, including referencing style The Bibliography (5%) The bibliography should demonstrate your knowledge of the field in which you have decided to conduct your research. It should be a working bibliography, not a final one. That is, we do not expect you to have read all the scholarship for your dissertation already, but we do expect you to have a good idea of what you will have to read as part of your research. Although the lengths of bibliographies vary widely, good MA dissertations normally have a bibliography of around thirty items. The bibliography should be formatted according to the MHRA Style Guide (http://www.mhra.org.uk/Publications/Books/StyleGuide/index.html). Be sure to include a list of the primary sources that you intend to use. Credit will be given for: coverage of important scholarship relevance to the topic correct formatting (according to the MHRA Style Sheet) The Oral Presentation (15%) When embarking on a research project, scholars try out their ideas on other members of the research community, often by presenting their preliminary findings in conference papers. We mimic this process by requiring you to present your proposal for your dissertation as an Oral Presentation. At the beginning of June, we will meet for our own Dissertation Symposium, in which each student will present his or her proposal for the dissertation in a fifteen-minute Oral Presentation. The Roles and Rules will be the same as for the Oral Presentations given during the RDC. Note especially that you must not read from a script. You should ensure that your topic is comprehensible to the range of interests and knowledge represented in your audience, and you should support your communication with appropriate audio-visual aids. In this assessed presentation you will need to explain (briefly): the title of the dissertation the wider area of study from which your project arises the precise research questions and/or hypotheses that you bring to the task how they relate to the existing secondary literature of your topic: are you opening up a new front, extending an established one in a new direction, questioning received wisdom…? the type(s) of evidence you will use methodological problems associated with that evidence your expected conclusions The Oral Presentation will be double-marked by the two members of staff attending the Dissertation Symposium. They will use the marking criteria listed in Appendix 2 of this Handbook. 15 The Dissertation The Dissertation (75%) As the dissertation is an independent project, students are expected to arrange their own topics and supervisors. The programme directors are available to provide general advice about topics and suggestions for potential supervisors, but students are responsible for arranging to meet their supervisors, agreeing a dissertation timetable, and ensuring that their supervisors are provided with their summer address and are aware of any periods when they will not be available. Note that it is the students’ responsibility to keep in touch with their supervisors, not the other way around. Each student will be supervised for the dissertation by a member of staff teaching on the degree. The supervisor will help the candidate to select a manageable topic and provide guidance and help with the location of appropriate sources and secondary reading. The supervisor should meet with the candidate twice between the beginning of June and the beginning of September to discuss the dissertation and offer further guidance and suggestions. The supervisor may read a draft of the whole dissertation (including the bibliography) once, if it is submitted in adequate time (approximately a month before the final submission date, for example). It is advisable that the supervisor see at least part of the dissertation early during the summer so that any basic flaws in presentation can be corrected at the outset. The supervisor must ensure that the candidate is aware of any long periods when she/he will not be available. It is important for the supervisor and candidate to agree upon a dissertation timetable by the end of June, as members of the academic staff are not continuously available throughout the summer months. Please note also that a supervisor may be unable to contribute constructively to a dissertation if he or she is presented with a long draft late in the summer. The MA dissertation must: be 12,000 to 15,000 words long including footnotes but excluding bibliography and appendices. Remaining within the prescribed word count is part of the challenge of writing a dissertation, not an optional or unimportant detail; please note the College penalties for overlength work (p. 5 above). Quotations count towards the total and should thus be brief; quotations from foreign languages should be accompanied by a translation added in a footnote; translations, too, count toward the word count. Please note that appendices should be used for giving supporting data only; they must not contain additional discussion. contain an accurate word count at the end. be ANONYMOUS. Although the dissertation may seem to be a very individual piece of work, it is examined anonymously as are all other pieces of assessed work. For this reason, candidates should never include dedications, thanks to supervisors, or other personal expressions in their work. be typed in double-spacing, with pages numbered consecutively. have a table of contents with page numbers. be submitted in TWO hard copies to the History Postgraduate Office, and in one electronic copy to TurnItIn, by the deadline listed on the inside cover of this Handbook. Be sure to keep a copy for yourself. be submitted with the official coversheet. Be sure to write your candidate number accurately on the coversheet. be written in clear and grammatical English, properly spelled and punctuated. be provided with footnotes showing the sources that have been used, formatted according to the guidelines published in the MHRA Style Guide. be provided with a bibliography formatted according to the guidelines published in the MHRA Style Guide. be either work based on hitherto unused material or a new critical exposition of existing knowledge in an appropriate field of study. show an awareness of previous scholarship done in the area. be appropriate to a degree in Medieval Studies. be approved by the supervisor. be the candidate’s own work. Any quotation from the published or unpublished work of other persons must be clearly indicated as such and acknowledged: failure to do so will be considered an examination offence and will render the candidate liable to the penalties incurred by cheating (please see also the discussion of plagiarism in the RDC booklet). 16 The Dissertation Please consult the marking criteria in Appendix 1 at the back of this Handbook for information regarding how the dissertation will be assessed. Some advice: Start work on the dissertation as soon as possible: three months melt away very quickly. Right from the start, always take detailed notes, with full bibliographical details, including page references, for everything you read. You will not want to waste time at the end rushing back to a distant library for a detail that you omitted to note the first time around. If you are unsure about the best way to approach writing a longer piece of writing like this, seek help as early as possible. In addition to instructors on the degree, you may wish to consult a writing guide, such as: Nigel Fabb and Alan Durant, How to Write Essays and Dissertations: A Guide for English Literature Students, 2nd edn (Harlow: Pearson, 2005). Aim to have the whole dissertation in draft by the beginning of August. This gives your supervisor time to look it over carefully; it also allows you time for checking, correcting, and responding to your supervisor’s comments. Keep in contact with your supervisor and try to submit a draft chapter to her/him as soon as possible so that, if you are not on the right lines, the problem can be quickly corrected, and, if you are on the right lines, you can feel encouraged. Ensure that your supervisor can contact you, especially over the summer. Try not to go off at tangents: keep your main objective in mind and do not waste precious time on interesting sidelines. Do the most difficult and distant research first. Check very carefully before and after word processing. Ensure that footnotes correlate with numbers in the text. Remember that this is not your final word on the subject: the dissertation is unlikely to be published as it stands, and there is time for rethinking after the dissertation has been examined. Keep your department informed of illness or problems that might delay your submission. 17 Medievalists at Royal Holloway Dr Alastair Bennett, Lecturer in Medieval Literature. Specialises in Middle English literature, particularly the complex relationship between Middle English sermons and literary texts. (alastair.bennett@rhul.ac.uk) Dr Hannes Kleineke, Senior Research Fellow in the History Department. He specialises in the History of Parliament and has published a biography of Edward IV. Professor Caroline Barron, Professor of the History of London. Has written on various aspects of the history of London in the medieval period, on the reign of Richard II, and on medieval women. (c.barron@rhul.ac.uk) Dr Pirkko Koppinen, Senior Teaching Fellow in the Department of English. Specialises in Old English literature, with particular emphasis on semiotic approaches to Anglo-Saxon culture. (p.a.koppinen@rhul.ac.uk) Dr Clive Burgess, Senior Lecturer in Late Medieval History. Editor and author of numerous books and articles on late medieval urban religion in England. Dr Catherine Nall, Lecturer in Medieval Literature in the English department. Works on late medieval literary and manuscript culture, with emphasis on the relationship between war, politics and literature. (hannes.kleineke@rhul.ac.uk) (c.burgess@rhul.ac.uk) (catherine.nall@rhul.ac.uk) Dr Helen Deeming, Senior Lecturer in Music. Specialises in medieval music, the history of the book, and the history of musical notation. Dr Jenny Neville, Reader in Anglo-Saxon Literature. Specialises in Old English literature. She is currently working on the Old English riddles, but has previously written on the representation of the natural world, seasons, monsters, law codes, and chronicles. (helen.deeming@rhul.ac.uk) Dr David Gwynn, Reader in Ancient and Late Antique History. His primary field of research is the Later Roman Empire (AD 200-600), with a particular focus on the reign of Constantine the Great (the first Christian Emperor), the development of Christianity, and the interaction between Christianity and other religions. (david.gwynn@rhul.ac.uk) (j.neville@rhul.ac.uk) Professor Katie Normington, Vice-Principal (Staffing) and Dean of Arts and Social Sciences; Professor of Drama and Theatre. Has taught and researched in the areas of medieval and contemporary drama. (k.normington@rhul.ac.uk) Professor Jonathan Harris, Professor of Byzantine History. He has published widely on aspects of Byzantine relations with Western Europe, particularly in the periods of the crusades and the Italian Renaissance, and on the last centuries of the Byzantine empire. Dr Danielle Park teaches in the Department of History. She wrote her PhD thesis on the legal and social history of Crusader privileges. (Danielle.Park.2007@live.rhul.ac.uk) (jonathan.harris@rhul.ac.uk) Professor Jonathan Phillips, Professor of Crusading History. Has written on the diplomatic relations between the Latin Christian settlers in the Levant and Western Europe at the time of the crusades and on the First, second, and Fourth Crusades, as well as a general history of crusading. Professor Ruth Harvey, Professor of Medieval Occitan Literature in the French department. Specialist in medieval French poetry. She has edited the works of the troubadour Marcabru. (r.harvey@rhul.ac.uk) Professor Peregrine Horden, Professor of Medieval History. Works on the social history of medicine in the early Middle Ages, Byzantine and Western, and on the environmental history of the Mediterranean world. (p.horden@rhul.ac.uk) (j.p.phillips@rhul.ac.uk) Dr Stefano Jossa (Reader in Italian Literature). Works on the Italian Renaissance, particularly on the process of nation-building in Italy as expressed through literature. (n.saul@rhul.ac.uk) Professor Nigel Saul, Professor of Medieval History. Has published books on gentry and knightly families in medieval England and on church monuments, and chivalry, as well as a major biography of Richard II. (stefano.jossa@rhul.ac.uk) 18 Appendix 1: General Marking Criteria These are general criteria which apply to all work completed during the Medieval MA. More specific criteria for individual assignments may also be supplied. High Distinction 85-100% To award a high distinction, examiners will be looking for: conformity with the requirements of the assignment (i.e. word-length, format, etc) publishable quality the ability to plan, organise and execute a project independently to the highest professional standards exceptional standards of accuracy, expression, and presentation the highest professional levels of fluency, clarity, and academic style outstanding engagement with and analysis of primary sources leading to strikingly original lines of enquiry an outstanding ability to analyse and evaluate secondary sources critically and to formulate questions which lead to original lines of enquiry exceptional creativity, originality and independence of thought Distinction 70-85% To award a distinction, examiners will be looking for: conformity with the requirements of the assignment (i.e. word-length, format, etc) potentially publishable ideas, arguments, or discoveries the ability to plan, organise and execute a project independently to a professional standard excellent standards of accuracy, expression, and presentation fluency, clarity, and mastery of academic style strong engagement with and analysis of primary sources leading to original lines of enquiry the ability to analyse and evaluate secondary sources critically and to formulate questions which lead to original lines of enquiry creativity, originality and independence of thought Merit 60-69% To award a merit, examiners will be looking for: conformity with the requirements of the assignment (i.e. word length, format, etc) evidence of the potential to undertake original research given appropriate guidance and support high standards of accuracy, expression and presentation skilful handling of academic style sustained engagement with and analysis of primary sources some ability to analyse and evaluate secondary sources critically some creativity, originality and independence of thought work that is approaching the level of a distinction 19 Marking Criteria Pass 50-60% To award a pass mark, examiners will be looking for: conformity with the requirements of the assignment (i.e. word length, format, etc) the ability to engage in research involving a moderate degree of originality a competent standard of organisation, expression and accuracy competence in the handling of academic style sound knowledge and understanding of key sources of information the ability to construct coherent and relevant answer to questions work that is at a basic postgraduate level Marginal Fail 40-49% Examiners will award a marginal fail if they find: non-conformity with some of the requirements of the assignment insufficient knowledge and comprehension of essential sources of information poorly developed argumentation poor levels of clarity and accuracy in written presentation occasional errors and confusions little evidence of independent thought work that is slightly below an acceptable postgraduate standard Fail 0-39% Examiners will award a failing mark if they find: non-conformity with the requirements of the assignment work that is not recognisable as academic writing confused, fragmentary, or only rudimentary knowledge and comprehension of essential sources of information incomplete or incoherent argumentation a lack of clarity and accuracy in written presentation substantial errors and confusions no evidence of independent thought work that is clearly below an acceptable postgraduate standard 20 Appendix 2: Marking Criteria for Oral Presentations The following criteria will apply to the assessment of oral presentations. Distinction 70-100% The presenter demonstrated a strong engagement with and analysis of primary sources. The presenter demonstrated an ability to analyse and evaluate secondary sources critically and to formulate questions leading to original lines of enquiry. The presentation included potentially publishable ideas, arguments, or discoveries. The structure of the presentation was clearly evident and was appropriate to the topic and the context. Ideas were linked coherently and the stages of the presentation were explicitly signposted. The presenter commenced and concluded the presentation with professional confidence. Hypotheses, research questions, and expected conclusions were stated appropriately and methodological problems clearly addressed. Equipment and/or audio-visual aids were prepared to a professional standard and increased the effectiveness of the presentation; they did not impede the audience’s comprehension. The presentation ran exactly to time and was paced appropriately for the audience. The presenter used the pitch of his or her voice, eye contact, and body language to engage the audience throughout the presentation. The presenter had correctly gauged the audience’s needs and interpreted these in order to deliver a inspiring presentation. The presenter encouraged appropriate audience involvement and questioning and responded to questions with authority and originality. Merit 60-69% The presenter demonstrated a sustained engagement with and analysis of primary sources. The presenter demonstrated some ability to analyse and evaluate secondary sources critically. There was some evidence of creativity, originality and independence of thought The structure of the presentation was evident, but it could have been made more explicit. It was appropriate to the topic and the context. There was evidence of coherent links between most ideas; some stages of the presentation were clearly sign-posted. The presenter commenced and concluded the presentation appropriately. Hypotheses, research questions, and expected conclusions were partially stated. Methodological problems were partially addressed. Equipment and/or audio-visual aids were used to increase the effectiveness of the presentation. The presentation ran closely to time and was almost entirely paced appropriately for the audience. The presenter used the pitch of his or her voice, eye contact, and body language to engage the audience for most of the presentation. The presenter had made an obvious attempt to gauge the audience’s needs and to interpret these in designing the presentation. The presenter encouraged appropriate audience involvement and questioning and demonstrated knowledge and understanding in response to questions. 21 Marking Criteria Pass 50-60% The presenter demonstrated a sound knowledge and understanding of key sources of information. The presenter was able to construct a coherent and relevant answer to a research question. The presentation had a structure, but it may not have been entirely evident. It was appropriate to the topic and the context. There was evidence of links between most ideas, and some stages of the presentation were sign posted. The presenter commenced and concluded the presentation appropriately. Hypotheses, research questions, and expected conclusions were stated, but not always appropriately, and without addressing methodological problems fully. Equipment and/or audio-visual aids were used, although they did not noticeably increase the effectiveness of the presentation; nevertheless, they did not impede the audience’s comprehension. The presentation ran closely to time and was for the most part paced appropriately for the audience. The presenter was audible throughout the presentation and used eye contact to engage the audience. The presenter made some attempt to anticipate and fulfil the audience’s needs. The presenter demonstrated knowledge and understanding in response to questions. Fail 0-49% The presenter conveyed confused, fragmentary, rudimentary, or erroneous knowledge of essential sources of information The argument was incomplete or incoherent, or lacking altogether. The presentation lacked structure and was rambling or unfocussed. Ideas were not linked coherently. The presentation commenced and concluded with hesitation or confusion. Hypotheses, research questions, consideration of methodological problems, and expected conclusions were largely omitted. Equipment and/or audio-visual aids were not used, or were used ineffectively. The presentation ran severely over or under time, or had to be cut well before the presenter had finished, or was paced too fast or too slow to be effective. The presenter was partially inaudible and did not make use of eye contact to engage the audience. The presenter had not taken the audience’s needs into account in designing the presentation. The presenter gave responses to questions which were largely erroneous or had little or no relevance. Appeals The marks for oral presentations will be determined by two examiners, like all your marks for this degree, so there should be little reason to doubt their fairness. If, however, you wish to dispute your mark, you have the following options: You can repeat your presentation to a panel of departmental staff. You can repeat your presentation in a room where it can be videoed, so that it can be sent to an external examiner. 22