Dualism paper - St. Olaf Pages

advertisement

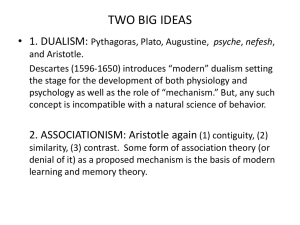

Wagnild 1 Elayna Wagnild Professor Rudd Philosophy 231 10/7/13 I’ve Lost My Mind! We live with the assumption that we have a mind. “That blew my mind!” “I think I’m losing my mind.” “I can’t make up my mind!” We say all of these expressions, sure that we have a mind to blow, to lose, or to make decisions. Is it necessarily true that we have a mind, though? It is possible, I suppose, that we are a body and our mind is something different, something separate from our body. Dualism is that idea that the mind and the body are inherently different. The body is a part of the physical world, while the mind is part of a different realm, a metaphysical realm. But others, reductionists, take the view that our body and mind are one; our mind is simply physical brain functions. So, which theory is most compelling? Descartes is a major figure in the debate on the body-mind issue, arguing from a dualistic perspective. In his Discourse 4, he says, …Intelligent nature is distinct from corporeal nature, taking into consideration that all composition attests to dependence and that dependence is manifestly a defect, I judged from this that being composed of these two natures could not be a perfection in God and that, as a consequence, God was not thus composed, but that, if there are bodies in the world, or even intelligences, or other natures that were not at all entirely perfect, their being had to depend on God’s power in such wise that they could not subsist without God for a single moment. (Descartes, Discourse 4, page 20) For most, it is easy just to buy into the whole idea of a mind and metaphysical realm. It is natural to reference something that is beyond the physical because we have been raised in a world where a theistic view, a belief in a metaphysical being, is Wagnild 2 very prevalent. For people who believe in something beyond the physical, therefore, dualism is a natural response to the mind/body problem. The idea of two separate realms explains the phenomena of consciousness and is a comfortable answer to how we function. We, as humans, live in our physical world, and our mind exists in another, less concrete world. Dualism perfectly complements theism. As Descartes argues, our intelligent nature is distinct from our corporeal nature. Descartes also argues that while the body and the mind are parts of separate worlds, they are also very closely linked, and the mind is “knowable.” In his letters to Princess Elizabeth, he tells her, “...[F]or the soul and the body together, we have only that of their union, on which depends that of the force of the soul for moving the body, and of the body for acting upon the soul by causing its feelings and passions (p. 13). Dualism is a wonderful theory for people who believe in a higher being or the possibility of a metaphysical realm. It makes the phenomena of consciousness easy to swallow by keeping the mind dependent on a metaphysical reality. For people who tend to think more scientifically and systematically, however, explaining the phenomena of consciousness by relying on a metaphysical reality can seem like a cop-out. By assigning the mind to a metaphysical existence, humans are able to categorize it as something magical, and simply leave it at that. How can we possibly understand something we have no control over? It is possible to begin to understand human reality without referring to the metaphysical. In functionalism, mental states are expressed by cause and effect. The mind and body are not separate; the mind is the body just responding to input. Wagnild 3 Functionalism is about cause and effect: mental states are causes, effects, and relations to other mental states. Jerry A. Fodor is a functionalist who thinks, “The chief drawback of dualism is its failure to account adequately for mental causation (The Body-Mind Problem 82).” He questions how a “nonphysical” mind is able to be in a physical space, and “…give rise to the physical without violating the laws of the conversation of mass, of energy and of momentum (The Body-Mind Problem 82).” Materialism is another body/mind theory where only matter exists and consciousness is the result of material interactions. J. J. C. Smart is a materialist who derides the idea of dualism by using Ockham’s razor, the idea that when presented with multiple hypotheses, one should go with the simplest hypothesis. Smart finds it hard to believe that everything but sensations and conscious states can be described by science. In his article titled Sensations and Brain Processes, he states, “It seems to me that science is increasingly giving us a viewpoint whereby organisms are able to be seen as physic-chemical mechanisms: it seems that even the behavior of man himself will one day be explicable in mechanistic terms (36).” Growing up, I went to church almost every Sunday. My grandfather and one of my uncles are pastors. My mother is on the church council. My sister was a religion major. I know theistic rhetoric inside and out. It would be easy to stay in the comfortable zone of assigning my mind to the metaphysical realm, and yet I find that place uncomfortable. When I came to St. Olaf, I began studying psychology and applying it to my knowledge of dance. My “mind” and body constantly work seamlessly together. Thought and movement are inseparable on the dance floor. While I am learning movement, my “mind” is constantly working. It tells me the Wagnild 4 sequence of movements, where I am supposed to be in space, and how my alignment should be working. Once I have the movement memorized, my “mind” is able to wander and think of non-dance related things. Farther down the process, there is a moment in time when it is obvious to me that my “mind” has shut off completely. Now, though, I am beginning to believe that it has always been my brain, and never my “mind,” making my body move. It learns the sequences, and patterns them into my memory. My brain learns the movements and signals my body to dance. Brain function does not need a metaphysical realm. (Although my dancing is often other worldly ;) ) A dualist view seemed plausible for my “mind” when I am dancing because of the moment when my body is moving, and my “mind” is thinking of non-dance things. It is like when Descartes talks about the body and the mind being unified. He says that it is something that we can’t understand, but we are able to experience it. It is a very first personal thing, just like dance is. Now, though, I question if it is plausible because I know my brain is learning the sequences of movement and signaling my body to move. I see Descartes point of view when he talks about the unity of body and mind, and only being able to understand it through experience. I also agree with Fodor when he talks about the conservation of mass, energy and momentum. It seems completely unnecessary to assign the mind metaphysical qualities when there is so obviously a direct connection between brain and body. I feel it every day when I dance. I agree with Smart, too. Why must we twist ourselves around so much, trying Wagnild 5 to explain our minds, when the simplest answer is so satisfying. My brain controls my body. However, I realize that I have not fully explored the study of the body/mind problem. Emotions are another phenomena we freely assign to the “mind.” It seems plausible to me that, as we begin to learn more about our brains, as the science behind brain function advances, we will understand how our brains facilitate emotion. I know that when I dance, when I feel my brain moving my body, I am filled with emotion. There must be a connection. So far, dualism, functionalism nor materialism offer me an explanation full enough to encompass emotion. It is possible, though, that someday I might change my mind! Works Cited Descartes, Rene. “Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One's Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences, Part Four.” 1637. Moodle. Eckert, Maureen. "Jerry Fodor, The Body-Mind Problem." Theories of Mind: An Introductory Reader. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006. 81-96. Print. Wagnild 6 Eckert, Maureen. "J. J. C. Smart, Sensations and Brain Processes." Theories of Mind: An Introductory Reader. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006. 35-45. Print.