Opening Statement by Prof. J. Kevin Nugent, Boston Children`s

Opening Statement to the Joint Committee on Health and Children,

Houses of the Oireachtas, Leinster House, Dublin 2

November 12, 2015

The first three years are a time of massive brain development, with lifelong implications for the child and for society.

J. Kevin Nugent, Ph.D., Director, Brazelton Institute,

Division of Developmental Medicine,

Boston Children's Hospital;

Lecturer, Harvard Medical School;

Professor Emeritus,

University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

1

Key Themes

The foundations of sound mental health are built early in life, so that early experiences—including children’s relationships with parents, caregivers, relatives, teachers, and peers—interact with genes to shape the architecture of the human brain.

Brain and biological pathways in the prenatal period and in the first 1000 days of life affect physical and mental health for the rest of our lives.

During the first three years of life, children’s long-term capacities to think, to trust, to feel concern for others, to understand and construct ideas are

being fundamentally shaped.

Neuroscience has highlighted the fundamental importance of early experiences on the developing brain and the associated risks of poorquality experiences and environments during the first three years.

Policies that support families are critical as the strength and quality of the relationship between parents and family and their children are fundamental to the effective development of children’s brain’s functions and capacity

Preventive intervention in the first years results in much higher economic returns than later interventions. It is never too late to intervene but by the time the child enters school it is very late.

2

Tá an-áthas orm bheith os bhúr gcomhair anseo inniú; is mór an onóir é.

Déanfaidh mé mo dhícheall bhúr gceisteanna a fhreagairt agus pé saineolaíocht atá agam a thabhairt daoibh. Go raibh míle maith agaibh.

I am especially pleased and privileged to have this opportunity to discuss some of the research in which my colleagues and I have been engaged for the past 35 years or so at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. I will summarise some of the evidence provided by the most recent discoveries in neuroscience about child health and well-being by focussing on the youngest members of our society, those who literally do not have a voice but whose voices need to be heard – infants and toddlers.

For much of the 20th century, many people, including behavioral scientists, severely underestimated the mental and social capacities of infants (Brazelton &

Nugent, 2011; Tenenbaum, Kemp, Griffiths and Goodman, 2011). We assumed that newborns could not see for example, that infants could not think or if they could their thought processes were concrete, immediate and extremely limited.

We also assumed that infants had a fragile, unreliable and narrow emotional range. We failed to be convinced that babies could grieve or be depressed or even traumatised. We – nurses, doctors, psychologists, therapists, teachers and even parents - tended to believe or perhaps wanted to believe that young children were inherently resilient and would simply “grow out of” their behavioral problems and emotional difficulties as they grew older (Osofsky & Thompson,

2000).

That infants and toddlers could develop mental health problems was beyond our ken.

The field of infant mental health had not yet emerged.

All that has changed. In the last 30 years, there has been a revolution in our scientific understanding of the capacities and the inner lives of babies and toddlers and in particular the workings of the infant brain. Brain development in the first three years of life is more extensive, more vulnerable to environmental influences and has a longer-term impact than was previously thought. Moreover, this accumulated body of evidence has confirmed that early relationships and parental caregiving play a critical role in the development of the child's brain; influences social, emotional, and cognitive development; and even mediates lifelong health outcomes (Brookes-Gunn et al. 2000; Shonkoff, Boyce, & McEwen,

2009).

3

While it was assumed that newborns, for example, functioned at a brain-stem level, we now know that the newborn at birth has most of the brain cells that she will have for her entire life and that t hrough experience, these neurons specialise and connect to organise into functional systems, beginning in pregnancy. In fact, we now know that the brain doubles in size in the first year, and by age three it has reached 80 to 90 percent of its adult volume. Even more importantly, synapses are formed at a faster rate during these years than at any other time. In the first few years of life, 700 to 1000 new neural connections are formed every second, as the brain builds connections or synapses.

Experience and Brain Development in the First Three Years (or the first 1000 days!)

The basic architecture of the brain is constructed through a process that begins soon after conception and develops sequentially and cumulatively (Champagne,

2015; Nelson et al. 2013; Shonkoff et al., 2009, 2012). The process of building the architecture of the brain is influenced by life experiences. It is not genetically hardwired. These neural connections are formed through the interaction of genes and a baby’s environment and experiences, though especially through interaction with adults. Neural connections that are used more often become stronger, such that repeated, regular, positive communication between a caregiver and infant will likely lead to a more positive parent-infant relationship .

These are the connections that build brain architecture the foundation upon which all later learning, behavior, and health depend (Center for the Developing

Child at Harvard University, 2010).

Caregiver responsiveness and sensitivity of the very young child has been found to be a major predictor of effective brain development and social emotional functioning (Shonkoff et al., 2005; Perry, 2009). This means that experiences such as children’s relationships with parents, caregivers, relatives, teachers, and peers shape the architecture of the developing brain. However, if a child experiences persistent chaos and unpredictability the developing neural systems and functional capabilities will reflect the disorganization .

I would like to make the case today that the foundation for sound mental health is built during these first years. Sound mental health provides an essential foundation of stability that supports all other aspects of human development— from the formation of friendships and the ability to cope with adversity to the

4

achievement of success in school, work, and community life. The first three years of life, therefore, are critical to the long-term outcomes for children as the rapidly developing brain is building its architecture. The strength and quality of the relationship between parents (and close family) and their children is seen as fundamental to the effective development of children’s brain architecture, functions and capacity. Sensitive and responsive caregiving is a requirement for the healthy neurophysiological, physical and psychological development of a child. W e also know that during the first three years of life, children’s long-term capacities to think, understand and solve problems, to trust, empathise and feel concern for others are being fundamentally shaped. While there are consistent findings in the literature that brain adaptation and learning is lifelong, we can now confidently assert that the child’s capacity to learn when he or she enters school is strongly influenced by the neural wiring that takes place in the first three years of life.

The effects of adverse experiences in the early years

Between birth and about age three, children’s brains are more malleable than they will be at any other stage in life, and the brains of very young children whose development is already compromised through genetic or environmental circumstances are more vulnerable than those of children growing up in stable, healthy environments.

Early experiences either enhance or diminish innate potential, laying down either a strong or a fragile platform on which all further development and learning is built. Because of the brain’s plasticity during the early period of rapid development, the younger the child the more vulnerable is their developing brain to the effects of the environment. Adverse environments can be particularly harmful and have long lasting effects, altering the developmental trajectory of a child’s learning. Compromised brain development in the early years increases the chances of later difficulties. While responsiveness and sensitivity of care of very young children has been found to be a major predictor of effective brain development and social emotional functioning (Bryck et al. 2012; Shonkoff &

Fisher, 2013), the longer children spend in adverse environments, the more pervasive and resistant to recovery are the effects.

Chronic, extreme stress during this period can damage the developing brain

(Center for the Developing Child, 2019; Shonkoff et al. 2012). Strong, frequent,

5

prolonged adverse experiences (toxic stress) such as extreme deprivation, repeated abuse, neglect, exposure to violence - without supportive adult relationships, can lead to changes in the physical structures and the functioning, including chemical responses, of the brain, impairing cell growth, changing the kinds of proteins and other molecules produced by the brain, death of neurons, interference with the formation of healthy neural networks. If children feel excessively stressed, fearful or anxious, neural processes are compromised and this can lead to decreased academic achievement, early school dropout, delinquency, drug and alcohol problems and mental health problems (Anda et al.,

2006; Perry, 2009). Sameroff has demonstrated that it is a combination of risk factors (depression, mother’s low educational attainment, lack of social support) rather than one factor alone, which has negative effects on children’s outcomes

(Sameroff, 2010).

Preventive Strength-based Models of Intervention

In the search for evidence-based guidelines for intervention, this body of research confirms the assertion that early experiences can either enhance or diminish innate potential, providing either a strong or a fragile platform on which future development and learning is built. The research we have reviewed has demonstrated the early years of life offer the greatest opportunity for preventing or mitigating harm from trauma and setting the course for optimal development

(Lyons-Ruth et al., 2003; Sheridan et al. 2012; Shonkoff et al. 2009).

Early disadvantage, such as the impact of poverty, ill health and other adversities, such as homelessness, can have a significant influence on children’s future progress, and are more often than not beyond the control of individual families. It is not poverty per se that makes the difference, but it is the kind of poverty that impoverishes the parent-child experience that leads to poor child outcomes rather than poverty of a material kind. Family characteristics correlated with income and parenting style (related to warmth/responsiveness, attachment and discipline), confidence and self-esteem (Halfon et al., 2003). While there is some compelling evidence that impoverished environments inhibit neural development, there is also a strong theme in the literature that positive stimulation will increase intellectual capacity (Halfon et al., 2003).

These research advances have resulted in an important paradigm shift in our understanding of early intervention by including an increased focus on a

6

strengths-based approach to prevention work with children and families as an alternative to a deficits-based model (Nugent et al., 2007, 2015). Whereas traditional intervention models aim at preventing a recurrence of maltreatment, for example, once it has already taken place, these approaches focuses on strengthening protective factors and building family and social networks to reinforce the ability of parents to care for their children. The aim is to strengthen the capacity of parents and communities to care for their children in ways that promote optimal health and well-being. In the case of child maltreatment, there is a shift toward the prevention–promotion framework that addresses child maltreatment before it occurs (primary prevention) and places it within the context of supporting parent capabilities. Preventing child maltreatment must also incorporate a focus on both increasing protective factors and decreasing risk factors.

Although they may use different terms and frames of reference, most researchers and theorists today agree on one thing: the importance of supporting healthy, satisfying relationships between infants and their primary caregivers. Positive relationships enable young children to develop self-confidence, sound mental health, the motivation to learn and to achieve, an understanding of the difference between right and wrong, the capacity to develop and sustain relationships, and, ultimately, the ability to be successful parents themselves (Sameroff, 2010;

National Council on the Developing Child, 2005).

In contrast, children who are deprived of positive relationships with caregivers in infancy may suffer impaired development that lasts into their adult lives. Thus, there is strong theoretical support for the notion that enjoying a secure relationship with caregivers is essential to infants’ social and emotional development. Supporting and engaging parents and families as an intervention strategy is therefore seen as fundamental to the effective development of children’s brain architecture, functions and capacity.

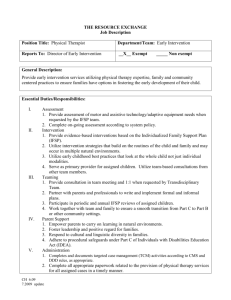

Professional Training in Infant Mental Health

As we have pointed out, supporting the relationship between parents and their young children is a primary task for early childhood professionals. Moreover, the emotional and behavioral needs of vulnerable infants, toddlers, and preschoolers are best met through coordinated services that involve parents, extended family members, home visitors, providers of early care and education, and/or mental health professionals. Consistent with the findings from the Growing up in Ireland

7

Longitudinal stud y (Williams, Greene, McNally, Murray, Quail, 2010), we believe that mental health services for adults who are parents of young children would have broader impact if they routinely included attention to the needs of infants and toddlers. By incorporating the skills and capacities of adult caregivers, creative new interventions could aid children whose developmental needs are not being met (Bryck & Fisher, 2012; Champagne, 2015; Nugent, 2015; McManus and

Nugent 2012; Shonkoff, 2013).

In Ireland, the field of infant-family mental health is an interdisciplinary field of study and practice that focuses on the social-emotional development and wellbeing of infants and young children within the context of their early relationships, family, community, and culture (Maguire, 2012). The Irish

Association of Infant Mental Health provides training to professionals to prepare them to promote early social and emotional development in babies and toddlers and the establishment of healthy and secure attachment relationships The goal is not just to treat existing problems, but also to prevent problems from developing in the first place (Osofsky & Thompson, 2000; Weatherston et al. 2009). As we have pointed out, practice and research on the first three years of life, on newborn and early behavior, on parent-child interactions, on attachment, on factors that influence early brain development and on intervention have radically changed clinical practice with infants and their families in recent times.

We believe therefore that physicians, nurses, teachers, social workers, providers of

Early Care and Education, physiotherapists and occupational therapists, speech therapists – and anyone who has responsibility for the care of infants and toddlers – be required to seek professional training in Infant Mental Health to enable them to understand and manage the emotional and behavioral problems of very young children and their families . Action is therefore imperative to reduce the burden of mental health problems in future generations and to allow for the full development of vulnerable children throughout the country.

Conclusions and Implications for Public Policy

I have tried to present an evidence base to support the development of policies, resources and optimal environments for children, while being mindful of other evidence bases that recognise the combined responsibilities of family, community and governments to promote the healthy development of all young children.

Policies that support families are critical as the strength and quality of the relationship between caregivers and family and their children are fundamental to

8

the effective development of children’s brain’s functions and capacity. This approach puts families and children in the center of a multifaceted model that includes building protective factors for families, reducing risk factors for children, strengthening local communities, and connecting all of this to systems change and policy. All adults who spend significant time with young children have a responsibility to help them develop to their full potential. That is why we focus here is on caregivers, a term that includes all adults who have regular contact with infants and toddlers--such as parents, grandparents, foster parents, child care providers, etc.

James J. Heckman, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2000 for his innovative work on the economics of human development, analyzed investments in early childhood programs and determined that the greatest gains can be made at early ages, because the social and cognitive skills learned by the very young set a pattern for acquiring important skills later in life. He believes that early interventions result in much higher economic returns than later interventions.

Research on the effects of educational programs for infants and toddlers show that investment in high-quality early childhood development for disadvantaged children yields an 8 to 10% annual rate of return through better education, health, and social outcomes (Heckman, 2006). Investing in education in the early years generates economic development for communities in the form of jobs and the purchase of goods and services, and makes for a more efficient workforce.

Above all, children who receive quality early experiences arrive at school ready to learn. As a result, they do better in school and need fewer costly special education classes. They also are more likely to graduate from secondary school and to hold jobs. Heckman’s message, that high-quality early intervention can narrow the economic divide may be relevant today as you are faced with difficult decisions about how to use funds to benefit children and families.

Key Messages for the Committee

Neuroscience has highlighted the fundamental importance of early experiences on the developing brain and the associated risks of poor-quality experiences and environments during the early years, particularly, the first three years. Meeting the developmental needs of very young children is as much about building a strong foundation for lifelong physical and mental health as it is about enhancing readiness to succeed in school. In other words, significant progress in lifelong

9

cognitive, social-emotional and health promotion could be achieved by reducing the burden of significant adversity on young children—and this progress could be accelerated through science-based enhancements in a wide range of policy domains, including child care and early education, child welfare, public assistance and employment programs for low-income parents, housing policies, and community development initiatives, to name just a few.

Policies that support families are critical as the strength and quality of the relationship between parents and family and their children are fundamental to the effective development of children’s brain’s functions and capacity. I hope I have demonstrated the need for multidisciplinary infant mental health training programmes that will enable professionals to understand and manage the emotional and behavioral problems of very young children and their families and to initiate programmes that will promote the kinds of infant and toddler experiences that will foster brain development, remediate early difficulties and prevent later problems for infants and their families.

Finally, I would like to thank you for giving me this privileged opportunity to address you.

10