The relationship between graduate development

advertisement

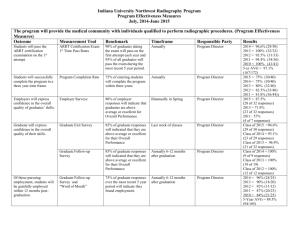

The relationship between graduate development programs and organisational commitment in the construction industry. Guinevere Gilbert Lecturer, School of Property, Construction and Project Management, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia. Guinevere.gilbert@rmit.edu.au Stream: Assessment, measurement and evaluation of HRD Refereed paper 1 8/02/2016 ABSTRACT Purpose Sequential mixed methods research was conducted to evaluate the success of graduate development programs implemented by construction organisations. The current paper reports on the second phase of the investigation which presents the likelihood of retention in the organisation as a result of experiencing a GDP. Methodology Semi-structured interviews of graduates and HR managers identified implemented developmental activities at the same time as quantitative measurement of commitment using the Three Components Model of commitment tool. Findings The overall results show no statistically significant increase in any form of commitment as a result of participating in a GDP. However results reveal a “trend in the right direction”: higher affective and normative commitment and lower continuance commitment where GDPs are implemented. Detailed analysis shows job rotation and attending more than one interview were associated with desirable outcomes. Implications These results are important because GDPs and their benefits might be perceived as a privilege associated with large employers; in reality, multiple interviews during recruitment and job rotation can both be implemented by all construction organisations, regardless of size. All construction organisations should be encouraged to implement carefully designed development programs. Keywords Graduate, development, commitment, construction. 2 8/02/2016 Introduction In the late 20th century, literature reported that construction organisations were slow to adopt innovative HRM strategies such as the design and implementation of formal development programs (Druker, White, Hegewisch & Mayne, 1996). Reasons given for this include the dominance of small organisations; contracted or transient labour; economic fluctuations not facilitating long term return on investment in HRD and the temporary human resource demands of construction projects (Druker et al., 1996; Dainty et al., 2000). There is some evidence that in the early 21st century, construction organisations changed their perception of the importance of human resource management. Raiden (2004) found that large construction organisations demonstrated significant investment in human resource development with the intended outcome of improved staff retention. Retaining qualified staff is an important outcome for organisations. The cost of recruiting and training staff is estimated to be equivalent to 75% of the annual salary (inSync, 2012) where the cost includes reduced productivity during the recruiting and training process as well as the cost of advertising and selecting the replacement. Further, the organisation loses unquantified skills and knowledge when an employee resigns. Formal development programs are a structured series of professional development activities implemented by an organisation. The general aim of such programs is the development of knowledge and skills to enhance job performance and achieve organisational goals. Graduate development programs as a subset of general development programs are characterised as having a limited lifespan, typically of two to three years, and having the outcomes of providing future managers for the organisation at the same time as developing skills the organisation perceives to be important (Gilbert, 2011). Arnold and Mackenzie Daveys’ seminal work in the 1990s explored the role and outcomes of such programs that specifically target graduates. They conclude that the suggested benefits of 3 8/02/2016 GDPs run by large organisations include increased employee commitment, job satisfaction, motivation and decreased intention to leave (Arnold and Mackenzie Davey, 1994a; Arnold and Mackenzie Davey, 1999; Sturges, Guest and Mackenzie Davey, 2000). This work was the first to explore the specific development strategies for graduates, but although they included a range of industries, the construction industry was not one of those. In the early 21st century, we have no clear picture of the nature of, and success of, graduate development in an industry still apparently trying to rid itself of its sleepy HR reputation. The research reported here was conducted to evaluate the success of graduate development programs (GDPs) implemented by construction organisations. The first phase established how construction organisations define “success” with regard to their GDPs. This phase defined success as retention of graduates as employees and future managers. As a result, the second phase examined the relationship between the presence of GDPs and graduate retention. The phase two research uses the Three Components Model of commitment (TCM) by Meyer and Allen (2004) as the framework for the study, accepting the relationship between retention and commitment which is widely reported. The complete investigation is reported by Gilbert (2011). The current paper reports on the second phase of the investigation only; it presents the relationship between formal graduate development programs implemented in the construction industry in Melbourne, Australia, and graduate commitment. The findings argue that specific developmental activities have a strong association with organisation commitment. The implications of such findings are that these activities are not the exclusive domain of the few large construction organisations, but can be implemented at low cost by the many small construction organisations. The research question asked: is there a significant relationship between graduate development programs in the construction industry and organisational commitment? The hypothesis to be argued is that graduates employed by construction organisations implementing a graduate 4 8/02/2016 development program are more committed than graduates employed by construction organisations not implementing a graduate development program. Literature review Construction industry The construction industry is characterised by many small enterprises, with few large organisations undertaking the very public commercial work. In 2014 only 1.5% of construction enterprises have more than 20 employees and concentration of work is low 62.7% of enterprises generate less than $200,000 in annual revenue (IBISWorld, 2014). Work undertaken by the industry is project work, ie. temporary, unique, with a definite outcome. This project focus means organisations find it harder to maintain consistent demand for human resources. This is partly responsible for the apparent sluggishness with which construction organisations have taken up innovative HR management behaviour. In 1996 Druker, White, Hegewisch and Mayne reported that the construction industry failed to keep up with modern human resource management trends. HRD techniques, in particular, lagged. Reasons for not implementing HRD and other training activities are: line managers being reluctant to allow their staff the necessary time away from work, employees being viewed as a factor of production whose cost should be minimised, the reduction in direct labour employed by large construction firms; the emphasis on productivity, not the people; economic fluctuations not facilitating long term return on investment in HRD; issues associated with creating a unique product in situ, geographically dispersed and outside; and labour commonly recruited as contractors, reducing the need for human resource management functions and delegating HRM to relatively unqualified project managers (Dainty, Bagilhole and Neale, 2000; Drucker et al., 1996). This is despite the industry being labour intensive; demand is high for blue collar trades-people since, even with the increase in off-site manufacturing, the skills required to assemble the 5 8/02/2016 components of a building are not the kind of skills a machine can be programmed to carry out. In the late 20th century, UK based research concluded that only 17% of large construction companies have a formal management development policy (Mphake, 1989) and that small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in construction failed to train employees in both technical and generic skills (Department for Education and Employment, 2000). More recent data from Australia shows that amongst construction organisations, training peaks in the 25 – 34 age group and that more people attended shorter courses in 2005 compared to 1997 (ABS, 2005). Gilbert (2011) suggests that a high proportion of training is externally legislated (such as work health safety) followed in popularity by informal on-the-job training, particularly in small and medium enterprises. Retention of graduates in construction organisations is not well documented. Young reported in 1991 that construction companies have a particularly low graduate retention rate. In 2000, Dainty et al. found that participants in graduate development programs in the UK aged 20 – 26 were satisfied that their expectations were being met. However respondents indicated training and development was provided on an ad hoc basis and they are expected to be pro-active in seeking opportunities to enhance their own development. Raiden, Dainty and Neale found in the early 2000s that large organisations do have some long term HR planning activities (Raiden, Dainty & Neale 2004). Raiden et al. propose that the concept that the construction industry is not implementing human resource development is largely anecdotal and Raiden (2004) reported that large UK construction organisations demonstrated significant commitment towards human resource development with the outcome of improved staff retention. 6 8/02/2016 General graduate development Throughout this research, GDPs are defined as a documented series of development activities arranged by the employing organisation, specifically for graduates to undertake. Organisational benefits of GDPs include achieving the best person-job fit, identification of potential leaders, promotion from within the organisation, enhancing team effectiveness, increased leadership in global market and increased organisational performance, enhanced job performance and increases in a number of other positive outcomes such as effectiveness at task, organisational commitment, motivation, satisfaction, productivity and skills (Arnold, 1997; Arnold & Mackenzie Davey, 1994a; AITD, 1991; Guest & Mackenzie Davey, 1996; Sturges et al., 2000; Goldstein & Ford, 2002; Jacobs & Washington, 2003). Examples of individual benefits include self-development skills (Guest & Mackenzie Davey, 1996), personal and professional growth and self-direction (Gutteridge et al., 1993), enhanced self-determination and growth (AITD, 1991). Increased employability is an individual benefit but this is a negative outcome for the organisation as graduates seek to increase their responsibilities in other organisations, hence the investment in their development is not returned. Evaluation of development programs records achievement of the desired benefits and return on investment, and ensures the most effective cutting-edge training methods are adopted. A very pragmatic suggestion is made by Giangreco, Carugati & Sebastiano (2010), that the nature of evaluation is proportionate to the formality and the size of the organisation implementing the program; large organisations should be thorough and evaluate the program, the resultant skills and any improvements across company performance. Small and medium enterprises and organisations with limited HRM facilities should carry out basic evaluation of the training itself. Despite agreement that evaluation is essential, Brinkerhoff (2005) states that most organisations fail to carry out training 7 8/02/2016 evaluation. Reasons for this include the belief that evaluation is not necessary (Swanson, 2005) and fear that the results may reveal the training is not successful (Spitzer, 1999). As the debate continues, it has become clear that whilst not many training programs are evaluated thoroughly, rather than admonishing small organisations for inadequate evaluation, they should be applauded for implementing and evaluating any training at all. After all, as Giangreco et al. (2010) point out, whilst evaluation should strive to supply the most complete picture, an incomplete picture is better than no picture at all. Commitment The Three Component Model (TCM) of commitment was developed by Meyer and Allen in 1991 and later revised and updated in 1997. The model states that commitment “characterises the employee's relationship with the organization” and has “implications for the decision to continue membership in the organization” (Meyer and Allen 1997, p. 67). The word ‘component’ in the model is indicative of each of three components. Affective commitment (AC) refers to the emotional attachment or identification with, and involvement in, an organization. Strong affective commitment indicates that an individual remains committed to an organization because that is what they want to do (Meyer and Allen, 1997). Normative commitment (NC) recognises individuals’ feelings of obligation and loyalty to an organisation. The third component, continuance commitment (CC) is an individual’s perception of two factors external to their control: losses to be borne if they left the organisation, and alternative employment opportunities. (Meyer, Becker and Vandenberghe, 2004). The relationship of continuance commitment with productivity is negative, and it is thought to be an indicator of an employee’s intention to leave. The antecedents of the three forms of commitment come from different sources: AC is caused by variables found in the nature of the role and the environment in which it is carried out in (job challenge, autonomy, variety of skills used, role clarity, decision 8 8/02/2016 making, workplace relations and fulfilling experiences). NC can be developed through socialisation and subsequent investment in an employee. The causes of continuance commitment are perceived to be outside of the employee’s control – either the losses associated with leaving, or the lack of alternatives. Continuance commitment can result in a feeling of being trapped. There is some debate, but it is generally accepted that organisational commitment has many positive influences including reduced absenteeism and turnover (Lee, Lee and Lum, 2008; Gellatly, Meyer and Luchak, 2006). Although dated, Porter et al. (1974) provide an interesting concept: as the individual nears their point of departure, commitment to the organisation decreases so that the gap between commitment amongst stayers and commitment amongst leavers grew larger. This ability to predict intention to leave could allow managers to implement an intervention to increase commitment and reduce turnover. No further research has attempted to observe this potential warning sign. Early career commitment Since this study investigates commitment amongst graduates, it is important to review what is known about commitment during the early career years. Early career commitment phases have been identified as pre-employment, entry or socialization, and a stabilization phase (Beck and Wilson, 2001). Whilst there is acceptance that commitment is not static throughout a career, the change in commitment in the first year is not consistent. Meyer, Bobocel and Allen (1991) conclude that the first month of employment is critical to development of affective commitment and that affective commitment after one month can predict affective commitment at six and eleven months. But Sturges, Guest, Conway and Mackenzie-Davey (2002) noted that affective commitment was high when first employed and fell significantly over the first twelve months. They also reported that early organisational career management tactics were not significantly associated with increased 9 8/02/2016 organisational commitment twelve months later, and so organisations should take great care when choosing activities to be included in their socialization programs; a theory not supported elsewhere. Antecedents thought to assist the development of affective commitment during socialization and the early career phase include recruitment processes, quality work experiences, identifying the needs and preferences of new graduates and structuring early work experiences to be compatible with these needs (Meyer, Bobocel and Allen, 1991), and face to face socialization (Wesson and Gogus, 2005). Meyer and Allen (1991) conclude that “Organisations can be instrumental in the development of affective commitment in their employees… for example provide job seekers with accurate information, provide new hires with quality work experiences” (1991, p. 733). Commitment in the construction industry Reflecting the adoption of HR behaviour, commitment in the construction industry has received little attention (Lingard and Liu, 2004). Much of the research investigating commitment within this context has sought to identify the antecedents of commitment within minority populations in the industry. For example, Liu, Chiu and Fellows (2007) investigated the impact of work empowerment on commitment amongst quantity surveyors in Hong Kong. Lingard and Lin (2004) explored commitment amongst women in construction; career progression as a result of career management and sufficient training opportunities were found to be predictors of organisational commitment. This suggests that the current research might find that where training is provided, commitment and retention are increased. This is despite the graduate having just completed several years of tertiary education, and it requires clarification – is it the provision of training itself that is a predictor of commitment, or career management, of which training is a component, that is a predictor of commitment? 10 8/02/2016 Dainty, Bagilhole and Neale (2000) explain, during the early career stage career expectations of construction graduates were met through the “structured nature of their progression” through a graduate training program (Dainty et al., 2000, p.172). Promises about career opportunities appear to be most predictive of employees’ intentions to leave and of their job search behaviours, and is also strongly predictive of employee loyalty. Career development should be considered as a core practice for both psychological contract fulfilment and for employee retention; where violations of training obligations occur, it has resulted in reduced organisational commitment (Granrose & Baccili, 2006). Method The aim of this research was to establish if there is a relationship between graduate development programs in the construction industry and organisational commitment. The research is undertaken from a positivist perspective and it is deductive; a theory and hypothesis are tested. The research aims to observe the indicators of one “event” (commitment) following another (a formal development program for graduates). A public database of registered builders with head office locations in Melbourne’s CBD provided the population of 29 construction organisations who were invited to participate. Of these, nine organisations agreed to participate in the research. Only four of the organisations implemented a formal, documented GDP; all of these organisations employ more than 100 people. The remaining five organisations carried out informal training, ie. not planned or documented. Of these, only one was categorised as a medium organisation with 15 employees; the remainder had in excess of 21 and the largest organisation to implement informal training had 200 employees. From the nine organisations, 28 graduates participated in the data collection; 12 graduates were engaged in a GDP, 16 were employed by organisations without a formal development program. 11 8/02/2016 The research conducted semi-structured interviews of graduates to identify implemented training and development activities. Graduates also completed the Three Components Model of commitment tool (Meyer and Allen, 2004). The TCM is reported to be reliable and is highly regarded internationally. Analysis of the data results in alpha values of 0.796 for both the affective and continuance commitment scales, and thus indicate good reliability. However the alpha value of 0.683 for the normative commitment scale is below that recommended to indicate good reliability. Caution will be used in interpreting any significant results relating to normative commitment. The analysis of the data was carried out on SPSS. The independent samples t-test carried out on the whole sample, then on the sample undertaking a GDP and finally on the sample not undertaking a GDP revealed three significant results which are explored. Whilst the sample size might be too small to establish a relationship between the two variables, the study is able to make tentative suggestions regarding the impact of GDPs in construction organisations based in Melbourne. Findings GDPs and commitment The overall results show no statistically significant increase in commitment as a result of participating in a GDP. This result is for affective, normative and continuance commitment. Analysis revealed what is reported to industry as a “trend in the right direction”: higher affective and normative commitment and lower continuance commitment was observed where a GDP was implemented compared to informal development. The sample who participated in a GDP showed a mean affective score of 31.42, a mean normative score of 28.3 and a mean continuance score of 16.00. The sub-group who did not participate in a GDP showed a mean affective score of 29.94, a mean normative score of 27.88 and a mean continuous score of 12 8/02/2016 17.88. These results are very similar, but show a slight positive trend amongst those graduates who experienced a GDP, with higher desirable commitment and lower undesirable commitment than those not experiencing a GDP. However none of these results are statistically significant (Table 1). Mean score GDP No GDP p 30.57 31.42 29.94 NS 28.07 28.33 27.88 NS 17.07 16.00 17.99 NS Affective commitment score Normative commitment score Continuance commitment score Table 1: Commitment scores by training Significant findings After analysis of the data, three statistically significant results were found which will be further explored: 1. affective commitment was significantly higher where job rotation occurred, for the whole sample (t(26)=2.108, p=.045, 95% CI=(.103, 8.102), r=.55) 2. affective commitment was also significantly higher where job rotation occurred for the sub-sample who did not experience a GDP (t(14)=2.274, p=.039, 95% CI=(.369,12.613), r=.52) 3. for those graduates not undertaking a GDP, mean continuance commitment scores were significantly lower where they were interviewed twice during the recruitment process (t(13)=2.402, p=.032, 95% CI=(.687,12.980), r=.55). 13 8/02/2016 Each of these significant results is explored. Job rotation and affective commitment. Where job rotation occurs, the mean affective commitment scores are significantly higher for two sample groups: the complete sample, and the sample not undertaking a GDP. For all graduates there is higher AC where job rotation is experienced (32.7) compared to those not experiencing job rotation (28.6). Amongst the graduates not experiencing a GDP, but who undertook job rotation as part of informal training, the difference between the “haves” (job rotation) and the “have nots” (no job rotation) is bigger: the mean affective commitment was 34.4 – significantly higher than for those who were not in a GDP and who did not experience job rotation whose AC was 27.9. It is thought that where job rotation occurs as part of a GDP, the impact of job rotation is lower than it is when job rotation is implemented without the foundation of a GDP. The research reports that job rotation had a positive influence on affective commitment. Thirteen out of 28 graduates experienced job rotation which is defined as the process of experiencing different roles in the organisation over a period of time, usually two – three years. The process of job rotation involves graduates moving laterally between roles, either intraproject or inter-project. Construction projects require different roles at different phases and this facilitates graduates moving from one role on a project to a different role on the same project as the project progresses; this is regarded as intra-project rotation. Rotation intraproject is commonly dictated by the progression of, and skill needs of, the project. Interproject rotation is more likely to occur in conjunction with a necessity for graduates to experience certain pre-determined roles for a pre-determined period of time. It is usually implemented in response to a planned, documented development program at the completion of which, a graduate has a set of skills acquired during the rotation. Job rotation meets a 14 8/02/2016 number of graduate needs: balance between variety and uncertainty, challenge and skill development. Each of these needs has been associated with affective commitment in previous research. Multiple interviews and continuance commitment Amongst the sample that did not undertake a GDP, experiencing more than one job interview resulted in a lower mean continuous commitment score (M=13.17, n=6) compared to the graduates who only had one job interview (M=20.00, n=9). This was the only significant result relating to continuous commitment (p=.032). Since continuous commitment is an undesirable component for an organisation to observe, this is a positive result. This research suggests conducting multiple interviews lowers continuance commitment in two ways. Firstly, during each interview, information is exchanged about the organisation which then reduces uncertainty and moderates expectations of the graduate. The graduates are more informed about the organisation and they have more realistic expectations which may reflect the benefits of remaining with the organisation. These graduates are aware that they will not receive benefits (such as a car and health insurance) in the short term, and the graduates are therefore less likely to perceive these benefits as a reason for remaining with the organisation. Second, it is proposed that as the graduate learns about the organisation, they feel empowered to make an informed decision to accept the offer of employment rather than have it forced upon them. Without profiling the multiple interview informal training sub-sample, a low mean continuous commitment score indicates that this sub-sample do not perceive that they would lose anything of importance to them if they left the organisation, and this perception is 15 8/02/2016 strengthened when two or more recruitment interviews are conducted. Taking into account the commitment profile, the research concludes that this group are likely to simply be uncommitted. Graduates who had two interviews reported that the first interview seemed to be the more formal of the two, conducted by a senior representative of the organisation. The second interview included the organisation representative from the first joined by another manager, often a project manager. Discussion of results and implications Despite the lack of convincing statistical significance between the presence of a GDP and increased commitment, there was no evidence that a GDP is detrimental to commitment. Therefore the research encourages construction organisations of all sizes to implement some form of GDP. In small to medium construction organisations, the role of HR Manager is often played by the owner and director of the company and this person is under pressure to manage construction work. However where they are inclined to discuss career progression and development activities with graduates, and where this is documented, the results are likely to be increased commitment. The specific significant results relating to job rotation and multiple interviews are now explored. Job rotation Since the work of construction organisations is project based, job rotation may occur within a project, or between projects. Intra-project rotation often occurs in organisations which espouse the concept that the project takes priority. Some of the organisations representatives interviewed in phase one of the complete study (not reported here) commented that the project rules, since if the project is not financially successful, then no graduates can be employed. Thus rather than the organisation or graduate dictating the nature and duration of job rotation, project needs are given priority and graduates change roles accordingly. Intra-project rotation provides advantages for both 16 8/02/2016 the project and the graduate. The project benefits from team continuity throughout the project lifecycle. Where team members change mid-project, some disruption to progress occurs during the settling in of new members. However because the skill requirements of a construction project change over time, a graduate can be retained on the project and still experience different roles without the need for a change in the project team. Disruption to the project is minimised. Inter-project rotation occurs where an organisation places more emphasis on formal control over the experience that the graduate gains. Where job rotation is formally implemented, the employing organisation documents and controls the rotation, moving graduates around different roles on a calendar basis – usually between 3 and 6 months. A graduate experiencing inter-project rotation may get a wider variety of experience in a shorter space of time than a graduate experiencing intra-project rotation. But this may be accompanied by uncertainty from experiencing both new project cultures and colleagues at the same time as a new role. Whilst this finding linking job rotation to affective commitment is not ground breaking - both Campion, Cheraskin and Stevens (1994) and Ho, Chang, Shih and Liang (2009) find a positive relationship between job rotation and commitment - the specific impact on affective commitment takes previous studies one step further. Neither Campion et al. nor Ho et al. used the TCM so identification of the impact of job rotation on specific forms of commitment has, until now, not been possible. However Campion et al. (1994) find four benefits of job rotation which all go some way to explain the relationship observed in the current research: career affect benefits, organisational integration benefits, stimulating work benefits and personal development benefits. The relationship between job rotation and commitment may also be explained by the graduate need for challenge identified by Shaw and Fairhurst (2008) being satisfied by the variety of experiences acquired during rotation. Variety is an inherent 17 8/02/2016 characteristic of job rotation; graduates are aware that they will experience a change of role at a previously determined time in the future (formal job rotation) or they will experience a change of role as the project progresses (informal job rotation). Variety, acquired through a change in the role and responsibilities of the graduate - is perhaps more certain where job rotation is implemented formally. However job rotation in any form is not without its potentially negative influences through uncertainty and challenge. Preston and Goh (2013) find engineering graduates that experience formal job rotation are less satisfied than those who informally swap roles. They attribute this finding to the nature of the roles, or the feeling of being taken out of their comfort zone. Both culture change and the role challenge are known to cause stress in new employees. The potential uncertainty encountered by the graduate as a result of changing projects frequently could be reduced by providing adequate information to the graduate ahead of the role change and by implementing actions to encourage all project cultures and employees to align themselves with the overall organisation culture and strategy. Uncertainty could also be reduced through the provision of a consistent mentor. Graduates experiencing intra-project rotation benefit because they do not move between projects and experience new project cultures and team members; there is likely to be a reduction in uncertainty. It should also be noted that too much challenge may be just as detrimental to commitment as not enough challenge. Inter-project job rotation poses the risk of too much challenge as challenge occurs both with each new role as well as each new project and its associated culture and colleagues. The ability of graduates to embrace challenges is moderated by the organisation’s awareness that the challenge exists, and their ability and willingness to manage the degree of challenge faced by the graduate. One organisation interviewed in phase one of the research (not reported here) used the following analogy to explain their philosophy towards how graduates should take on challenges: “…you put them into a pool, you chuck 18 8/02/2016 them in and they flounder and they flounder but you’ve got to be there so that the moment they go under, right, you let them, they can go under for a little while, because that all builds stamina sort of thing but then you pull them straight back out so they’re up again… so they’ve got to be under a little bit of pressure”. If the graduate is unaware that they are being watched, then they may have the perception of being left to drown, to continue the analogy. What, then, is the relationship between job challenge and organisational support or mentoring and how does this impact affective commitment? It is suggested that the presence of a supportive environment or a successful mentoring relationship enables greater challenges to be taken on without a decrease in affective commitment. Literature does not address this question and this research recommends this should be the subject of future investigation. Although the research sample is small, the significance of the result discussed here is not threatened by unequal sub-groups. Therefore it is safe to conclude that job rotation is associated with an increase in affective commitment, and that job rotation should be encouraged within construction organisations, as part of the implementation of a GDP. However organisations should consider the advantages and disadvantages of formal interproject and informal intra-project rotation from the perspectives of the project and the graduate before deciding which form of rotation should take. Multiple interviews Graduates who experienced multiple interviews reported that the first interview seemed to be the more formal of the two, conducted by a senior representative of the organisation. This experience reported in this study relating to multiple interviews is reflective of current recruitment practices: Di Milia (2004) found 48.1% of organisational respondents to an Australian survey reported they always conduct more than one interview and that two to three people are present on interview panels. Interviews may take different forms; they may be formal, informal, face to face, on the phone, in out of work settings and may 19 8/02/2016 include tours of the facilities for short listed candidates (as recommended by Riordan and Goodman, 2007). These processes are intended to reduce the amount of uncertainty a graduate might feel prior to and in the early days of employment. Multiple interviews serve two purposes: firstly the applicant gains some knowledge about the organisation, its expectations and the role to be filled; this knowledge may reduce early uncertainty which stems from lack of knowledge (Feldman and Brett, 1983). When a graduate becomes an employee in an organisation about which they know relatively little, not being able to predict the future creates a threat which in turn causes anxiety. Since anxiety has negative effects, uncertainty reduction is therefore desirable. Knowledge gained can assist in framing realistic expectations. The correlation between expectations being met, and job satisfaction and intent to remain is confirmed by Wanous, Poland, Premack and Davis (1992). However the best intentions might not be translated into shared information. Riordan and Goodman (2007) found amongst their sample that organisations did not intentionally mislead graduates, but that they communicated nothing to create realistic expectations and in the absence of any guidance, graduates transferred their expectations to the organisation. Personal communication with a newly employed graduate revealed he still expected to be paid overtime and receive Rostered Days Off (RDOs are a feature of the Australian construction industry, and involve all construction firms in a designated region regularly scheduling a specific weekday as a rest day for tradespeople) as a graduate management trainee (personal communication, April 2009). Clearly the organisation had not communicated to the graduate that these conditions are directed at tradespeople and so the graduate had unrealistic expectations. Although this is a single case and it would be false to transfer this portrayal to the whole construction 20 8/02/2016 industry, clearly there are instances of insufficient information being communicated to graduate employees. The second benefit of multiple interviews is that an applicant can make an informed decision to accept a job offer. Continuous commitment is that brought about by having no alternatives. But the empowerment provided by knowledge about the organisation enables the lack of alternatives to be less influential, to appear less restrictive. Instead of focusing on the lack of alternatives, the graduate is focused on feeling positive about the organisation which made an offer of employment, because they are more familiar with the organisation. The process of multiple interviews allows the organisation to build a relationship with future employees. This result adds support to the findings of Meyer, Bobocel and Vandenberghe (1991) who confirmed that graduates who decided to accept the offer of employment of their own free will reported a lower continuance commitment score. Support is also provided for a range of interview techniques as proposed by Scholarios, Lockyer and Johnson (2003) who found that the more complex and interactive the selection methods adopted by the prospective employer, the lower the continuance commitment scores were. This should be balanced with overuse of different selection techniques which, Scholarios et al. claim can have the adverse effect of increasing continuance commitment. Although not a training activity, construction organisations should be encouraged to view job interviews as not just for the purpose of selecting the right individual, but also to inform the applicants about the organisation, its work, its expectations of graduates, and how the graduate is to be compensated for their efforts. To accomplish this, it is recommended that construction managers conducting interviews acquire some knowledge regarding interview best practice. Whilst multiple interviews are not shown to be related to higher affective and 21 8/02/2016 normative commitment scores, it is still beneficial to know that employees report lower continuance commitment score. Conclusion The research question asked if there is a significant relationship between graduate development programs in the construction industry and organisational commitment. The results indicate that there is a positive trend, but that the relationship was not significant amongst this population. This is quite possibly caused by a small sample size (a limitation of this study) and the research should be repeated with a larger sample such as one that includes a wider geographical area. The hypothesis that graduates employed by construction organisations implementing a graduate development program are more committed than graduates employed by construction organisations not implementing a graduate development program was not able to be supported. However the positive trend in commitment results should encourage construction organisations to continue to implement carefully designed graduate development programs. The research established that job rotation and conducting multiple interviews during recruitment do have a significant positive impact on affective and continuance commitment respectively. These results are important because GDPs and their benefits might be perceived as a privilege associated with large employers; in reality, multiple interviews during recruitment and job rotation can both be implemented by all construction organisations, regardless of size. 22 8/02/2016 References Arnold, J. (1997) Managing careers into the 21st century. London: Paul Chapman Publishing Arnold, J. & Mackenzie Davey, K. (1994a) “Evaluating graduate development: Key findings from the Graduate Development Project”. Leadership and Organisation Development Journal, 15, 9-15. Arnold, J. & Mackenzie Davey, K. (1999) “Graduates’ work experiences as predictors of organisational commitment, intention to leave and turnover: Which experiences really matter?” Applied Psychology: An International Review, 48, 211-288. Australian Bureau of Statistics (2005) 6278.0 Education and Training Experience, Australia. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Institute of Training and Development (1991) Career Development Practices in Selected Australian Organisations: An Overview of Survey Findings. NSW: AITD Beck, K. & Wilson, C. (2001) Have we studied, should we study, and can we study the development of commitment? Methodological issues and the development study of workrelated commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 11, 257-278 Brinkerhoff, R. (2005) The success case method: A strategic evaluation approach to increasing the value and effect of training. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 7,86101. Campion, M., Cheraskin, L. & Stevens, M. (1994) Career related antecedents and outcomes of job rotation. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 1518 – 1542 Dainty, A., Bagilhole, B., Neale, R. (2000) A grounded theory of women’s career underachievement in large UK construction companies. Construction Management and Economics, 18, 239-250. 23 8/02/2016 Department for Education and Employment (2000) Labour Market Skills and Trends 2000. London: DEE Di Milia, L. (2004) Australian management selection practices: Closing the gap between research findings and practice. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 42, 214-228 Druker, J., White, G., Hegewisch, A. & Mayne, L. (1996) Between hard and soft HRM: Human resource management in the construction industry. Construction Management and Economics, 14, 405-416. Feldman, D. & Brett, J. (1983) Coping with new jobs: A comparative study of new hires and job changers. Academy of Management Journal, 26, 258-272. Gellatly, I., Meyer, J. & Luchak, A. (2006) Combined effects of the three commitment components on focal and discretionary behaviours. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69, 331345. Giangreco, A., Carugati, A. & Sebastiano, A. (2010) Are we doing the right thing? Food for thought on training evaluation and its context. Personnel Review, 39, 162-177. Gilbert, G. (2011) A Sequential Exploratory Mixed Methods Evaluation of Graduate Training and Development in the Construction Industry. Unpublished PhD thesis, RMIT University , Melbourne. Goldstein, I. & Ford, J. (2002) Training in organisations: Needs assessment, development and evaluation. Belmont, CA: Wadswort Granrose, C.S. & Baccili, P. (2006) Do psychological contracts include boundaryless or protean careers? Career Development International, 11, 163-182. 24 8/02/2016 Guest, D. & Mackenzie Davey, K. (1996, 22nd February) Don’t write off the traditional career. People Management, 22-25. Gutteridge, T., Leibowitz, Z. & Shore, J. (1993) Organisational Career Development: Benchmarks for Building a World-Class Workforce. San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass. Ho W., Chang, C., Shih, Y. & Lian, R. (2009) Effects of job rotation and role stress among nurses on job satisfaction and organisational commitment. BMC Health Services Research, 9. IBISWorld 2015 IBISWorld Industry Report E Construction in Australia. IBISWorld. Viewed 29th March 2015. http://clients1.ibisworld.com.au/reports/au/industry/competitivelandscape.aspx?entid=306 InSync (2012) The 2012 Insync Surveys Retention Review. InSync Surveys, Sydney. Jacobs, R. & Washington, C. (2003) Employee development and organisational performance: A review of literature and directions for future research. Human Resource Development International, 6, 343-354. Lee, S., Lee, T. & Lum, C. (2008) The effects of employee services on organisational commitment and intentions to quit. Personnel Review, 37, 222-237 Lingard, H. & Lin, J. (2004) Carer, family and work environment determinants of organisational commitment among women in the Australian construction industry. Construction Management and Economics, 22, 409-420. Liu, A., Chiu, W. & Fellows, R. (2007) Enhancing commitment through work empowerment. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 14, 568 – 580. Meyer, J.P. & Allen, N.J. (1991) A three component conceptualization of organisational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1, 61-89. 25 8/02/2016 Meyer, J.P. & Allen, N.J. (1997) Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research and Application. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Meyer, J. P. & Allen, N.J. (2004) TCM Employee Commitment Survey Academic Users Guide. Department of Psychology, University of Western Ontario. Meyer, J.P., Becker, T. & Vandenberghe, C. (2004) Employee commitment and motivation: A conceptual analysis and integrative model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 991-1007. Meyer, J.P., Bobocel, D.R. & Allen, N.J. (1991) Development of organisational commitment during the first year of employment: A longitudinal study of pre- and postentry influences. Journal of Management, 17, 717-733. Mpake, J. (1989) Management development in construction. Management Education and Development, 18, 223-243. Porter, L. W., Steers, R., Mowday, R. & Boulian, P. (1974) Organisational commitment, job satisfaction and turnover amongst psychiatric technicians. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59, 603-609. Preston, V. & Goh, S. (2013) Engineering Graduate Program – how it affects the skills, attributes and career development of graduate engineers. Proceedings of the 2013 AAEE Conference, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia, Raiden, A. (2004) The Development of a Strategic Employee Resourcing Framework (SERF) For Construction Organisations. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Loughborough Univesity. Raiden, A., Dainty, A. & Neale, R. (2004) Current barriers and solutions to effective team formation and deployment within a large construction organisation. International Journal of Project Management, 22, 309-316. 26 8/02/2016 Riordan, S. & Goodman, S. (2007) Managing reality shock: Expectations versus experiences of graduate engineers. South African Journal of Industrial Psychology, 33, 67-73. Scholarios, D., Lockyer, C. & Johnson, H. (2003) Anticipatory socialisation: the effect of recruitment and selection experiences on career expectations. Career Development International, 8, 182-197 Shaw, S. & Fairhurst, D. (2008) Engaging a new generation of graduates. Education and Training. 50, 366-378. Spitzer, D. (1999) Learning effectiveness: A new approach for measuring and managing learning to achieve business results. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 7, 55-70. Sturges, J., Guest, D. & Mackenzie Davey, K. (2000) “Who’s in charge? Graduates’ attitudes to and experiences of career management and their relationship with organisational commitment.” European Journal of Work and Organisational Psychology, 9, 351-370. Sturges, J., Guest, D., Conway, N. & Mackenzie Davey, K. (2002) A longitudinal study of the relationship between career management and organisational commitment among graduates in the first ten years at work. Journal of Organisational Behavior, 23, 731-748 Swanson, R. (2005) Evaluation, a state of mind. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 7, 16-21. Wanous,J., Poland, T., Premack, S. & Davis, K. (1992) The effects of met expectations on newcomer attitudes and behaviors: a review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 288-297 Wesson, M.J. & Gogus, C.I. (2005) Shaking hands with a computer: An examination of two methods of newcomer orientation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 1018-1026. 27 8/02/2016 Young, B.A. (1991) Reasons for changing jobs within a career structure. Leadership and Organisation Development Journal, 12, 12-16. 28 8/02/2016