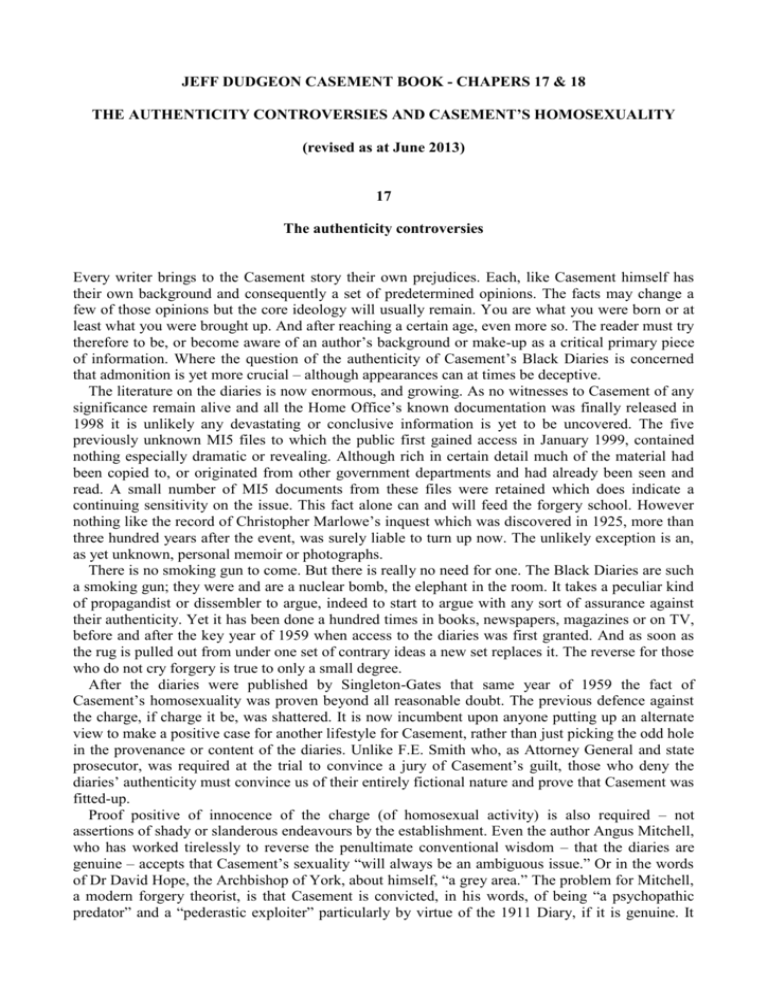

JEFF DUDGEON CASEMENT BOOK

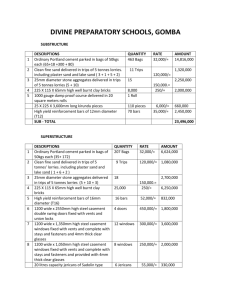

advertisement