TOOL MODULE: BRAIN IMAGING Source: McGill University

advertisement

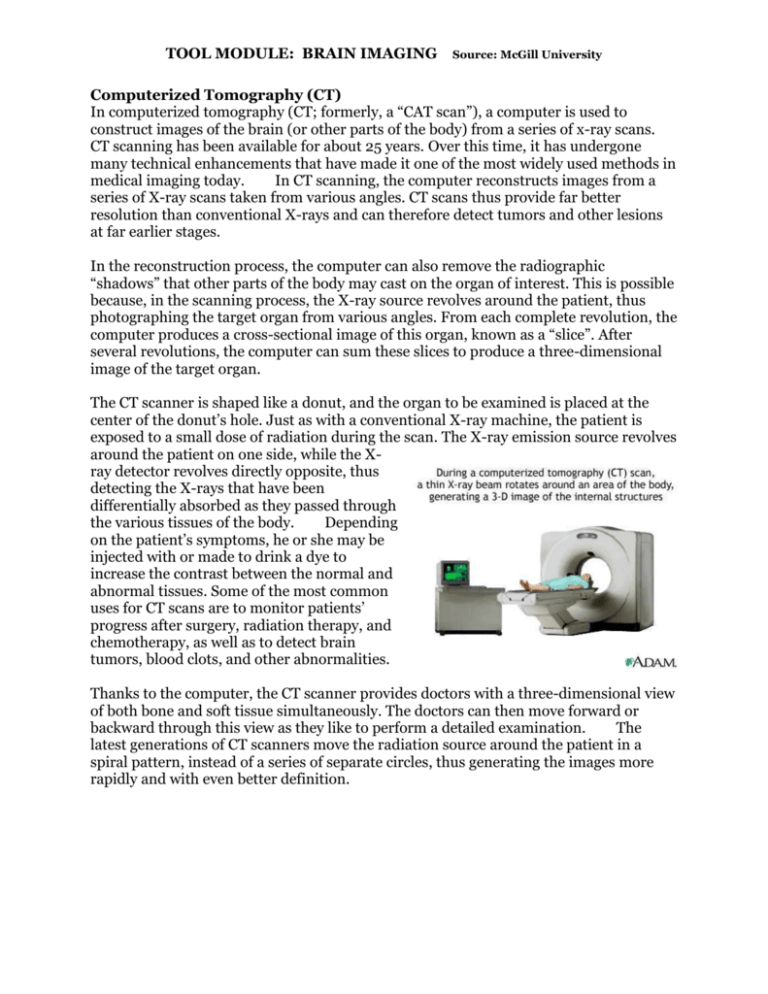

TOOL MODULE: BRAIN IMAGING Source: McGill University Computerized Tomography (CT) In computerized tomography (CT; formerly, a “CAT scan”), a computer is used to construct images of the brain (or other parts of the body) from a series of x-ray scans. CT scanning has been available for about 25 years. Over this time, it has undergone many technical enhancements that have made it one of the most widely used methods in medical imaging today. In CT scanning, the computer reconstructs images from a series of X-ray scans taken from various angles. CT scans thus provide far better resolution than conventional X-rays and can therefore detect tumors and other lesions at far earlier stages. In the reconstruction process, the computer can also remove the radiographic “shadows” that other parts of the body may cast on the organ of interest. This is possible because, in the scanning process, the X-ray source revolves around the patient, thus photographing the target organ from various angles. From each complete revolution, the computer produces a cross-sectional image of this organ, known as a “slice”. After several revolutions, the computer can sum these slices to produce a three-dimensional image of the target organ. The CT scanner is shaped like a donut, and the organ to be examined is placed at the center of the donut’s hole. Just as with a conventional X-ray machine, the patient is exposed to a small dose of radiation during the scan. The X-ray emission source revolves around the patient on one side, while the Xray detector revolves directly opposite, thus detecting the X-rays that have been differentially absorbed as they passed through the various tissues of the body. Depending on the patient’s symptoms, he or she may be injected with or made to drink a dye to increase the contrast between the normal and abnormal tissues. Some of the most common uses for CT scans are to monitor patients’ progress after surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy, as well as to detect brain tumors, blood clots, and other abnormalities. Thanks to the computer, the CT scanner provides doctors with a three-dimensional view of both bone and soft tissue simultaneously. The doctors can then move forward or backward through this view as they like to perform a detailed examination. The latest generations of CT scanners move the radiation source around the patient in a spiral pattern, instead of a series of separate circles, thus generating the images more rapidly and with even better definition. TOOL MODULE: BRAIN IMAGING Source: McGill University Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) When magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology emerged in the late 1970s, it had the impact of a bombshell in the medical community. The conventional imaging methods of the day relied on either X-rays or ultrasound. But MRI uses magnetic fields instead, thereby exploiting the physical properties of matter at the subatomic level, and especially of water, which accounts for about 75% of the mass of the human body. MRI scans not only provide higher-definition images than CT scans, but they can also show sagittal and coronal sections of the brain, not just the axial sections to which CT scans are limited. The operation of an MRI scanner is fairly complex, but the main steps can be summarized as follows. 1. The scanner’s magnetic field aligns the far weaker magnetic fields of all the protons in all the hydrogen atoms in the water contained in the body’s tissues. 2. The scanner then uses radio waves to bombard the part of the brain that is to be imaged. 3. After the radio waves are turned off, the protons return to their original alignment. In the process, they emit a weak radio signal, known as their magnetic resonance. The intensity of this magnetic resonance is proportional to the density of the protons in the various tissues, and hence to the percentage of water that they contain. 4. Special sensors detect the varying intensities of this resonance and relay this information to a computer. 5. The computer processes this information to create images of tissue sections along various axes. Before even entering the scanning room, much less being placed inside the scanner, the patient must remove any metal objects that might be attracted by the magnetic field. (People who wear prostheses or have arterial clips or pacemakers must avoid having MRIs, for obvious reasons.) The scanner produces a fairly loud noise, so the patient is also given earplugs to wear during the scan. The patient then lies down on the table shown in the foreground in the above picture. In order to obtain clear images, it is very important for the patient to lie as still as possible, so his or her head is secured by restraints. The patient and the table are then slid into the tunnel, which is scarcely more than shoulder-width. This tunnel contains the wires that generate the magnetic field, as well as the coils that receive the radio waves. Though CT scans are still the primary tool for imaging the chest and abdomen, MRI scans are the tools of choice for the brain, hands, feet, and spinal column. Diseased or damaged tissues generally contain more water, which allows them to be detected with MRI. For MRI scans, as for CT scans, the patient may be injected with a contrast agent. The agents most commonly used for MRIs are compounds of the element gadolinium, which serves the same purpose as iodine, but with less risk of allergic reactions. TOOL MODULE: BRAIN IMAGING Source: McGill University Electroencephalography (EEG) Many of the brain’s cognitive and motor functions produce characteristic patterns of neuronal electrical activity. Electroencephalography (EEG) is a method that amplifies these patterns and records them as distinctive signatures on an electroencephalogram (also abbreviated EEG). Electroencephalography measures the brain’s overall neuronal activity over a continuous period by means of electrodes glued to the scalp. Today’s computers can analyze the brain activity sensed by several dozen electrodes positioned at various locations on the scalp. The electrical currents picked up by these sensors are generated mainly by the dendrites of the pyramidal neurons that are found in massive numbers in the cortex. These neurons are oriented parallel to one another, which amplifies the signal from their common activity. The oscillations in an EEG can therefore be regarded as the sum of the various oscillations produced by the various assemblies of neurons, with all of these “harmonics” being superimposed on one another to produce the total recorded trace. For purposes of analysis, this trace has the same two characteristics as a sound wave: its oscillation frequency and its amplitude. The frequencies of brain waves range from 0.25 Hz to 64 Hz (1 Hertz equals 1 oscillation per second). A person’s state of consciousness (awake, asleep, dreaming, etc.) has a decisive influence on the frequency of his or her electroencephalogram. The frequency profiles associated with certain brain activities have already been identified. Thus the following types of brain waves may be found in an EEG: delta: < 4 Hz (deep sleep, coma); theta: 4-8 Hz (limbic activity: memory and emotions); alpha: 8-12 Hz (person is alert but not actively processing information; predominant in the occipital and frontal lobes, for example, when the eyes are closed); beta: 13-30 Hz (person is alert and actively processing information); gamma: > 30-35 Hz (might be related to communications among various parts of the brain to form coherent concepts). EEG recorded during an epileptic seizure EEGs offer excellent temporal resolution and are relatively inexpensive compared with fMRI or PET scans, but their spatial resolution is poor. Nevertheless, EEGs can help in diagnosing epileptic foci, brain tumors, lesions, clots, and so on. They can also help to locate the sources of migraines, dizziness, sleepiness, and other conditions. When EEGs are used to construct brain maps, procedures known as evoked potentials are often employed. In an evoked potential procedure, the subject is exposed to a particular stimulus (such as an image, a word, or a tactile stimulus) and the neuronal response associated with this stimulus in the brain is recorded on the EEG. TOOL MODULE: BRAIN IMAGING Source: McGill University TOOL MODULE: BRAIN IMAGING Source: McGill University Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) Unlike ordinary MRI, which is used to visualize the brain’s structures, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is used to visualize the activity in its various regions. The scanning equipment used and the basic principle applied in fMRI are essentially the same as in MRI, but the computers that analyze the signals are different. The physiological phenomenon on which fMRI (as well as positron emission tomography) is based was discovered in the late 19th century, when neurosurgeons found that the brain’s cognitive functions cause local changes in its blood flow. When a group of neurons in the brain becomes more active, the capillaries around them dilate automatically to bring more blood and hence more oxygen to them. Within the red blood cells, the oxygen is carried by a protein called hemoglobin, which contains an iron atom. Once a hemoglobin molecule releases its oxygen, it is called deoxyhemoglobin and has a property called paramagnetism, which means that it causes a slight disturbance in the magnetic field of its surroundings. This disturbance is used in fMRI to detect the concentration of deoxyhemoglobin in the blood. For reasons that will be omitted here, the increase in blood flow to a more active area of the brain always exceeds this area’s increased oxygen demand, so the deoxyhemoglobin present becomes diluted in a larger volume of blood—in other words, its concentration declines. It is this decline in the concentration of deoxyhemoglobin that fMRI interprets as increased activity in this area of the brain. If one fMRI image is recorded of the brain before the subject performs a task, and another is recorded while the subject performs the task, and the intensities of the same areas in the two different images are subtracted from each other, the areas with the largest differences will appear “lit up”. These areas represent the parts of the brain that are the most heavily infused with blood, and hence the areas with the greatest neuronal activity. Functional MRI of a 24-year-old woman during a wordgeneration task (Source : Dept. of Neurology and Radiology, Münster) The fMRI method was developed in the early 1990s, when increasingly powerful computers were coupled with MRI scanners. The recording time for fMRI images can be as short as 40 milliseconds, and the resolution—on the order of 1 millimeter—is the best among all the functional imaging technologies. The latest fMRI scanners can produce four photographs of the brain per second, so that researchers can watch areas of neuronal activity move around the brain while subjects perform complex tasks. The fMRI method can be used without having to inject any dyes into the subject’s body, so it is greatly valued in fundamental research. One of its other major advantages is that the same scanner can provide both structural images and functional images of a person’s brain, thus making it easier to relate anatomy to function. Many people regard fMRI as the imaging technique that yields the most impressive results. But the high costs of purchasing and maintaining fMRI scanners are also impressive, so their use must often be shared, and there are often long waiting lists. TOOL MODULE: BRAIN IMAGING Source: McGill University Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Positron emission tomography (PET), or “PET scanning”, was the first functional brain imaging technology to become available. It was developed in the mid-1970s. The physiological phenomenon on which both PET and fMRI are based was discovered in the late 19th century, when neurosurgeons found that the brain’s cognitive functions cause local changes in its blood flow. When a group of neurons in the brain becomes more active, the capillaries around them dilate automatically to bring more blood and hence more oxygen to this more active part of the brain. A person who is going to receive a PET scan must be injected with a solution containing a radioactive substance. This substance may be the water itself, or it may be radioactive glucose or some other substance dissolved in the water. Because the dilation of the capillaries will bring more of this solution to the more active areas of the brain, these areas will give off more radioactivity during the PET scan. A positron is an elementary particle that has the same mass as an electron but the opposite charge. The positrons emitted in a PET scan come from the decay of the radioactive nuclei in the solution injected into the person’s bloodstream. As soon as these positrons are emitted, they annihilate the electrons in the surrounding atoms, thereby releasing energy in the form of two gamma rays that move in diametrically opposite directions. A set of detectors placed around the person’s head measures the pairs of gamma rays emitted. The computer then uses the resulting data to calculate the position in the brain from which these rays came. Through massive calculations, the computer can thus reconstitute a complete image of the brain and its most active areas. Because the half-life of the radioactive substances used in PET scans must be short (about two minutes), these substances must be produced on site, which entails fairly high costs and thus limits the accessibility of PET scans. In addition to showing the functional activation of the brain and detecting tumors and blood clots, PET scans can be used to determine how particular substances are used metabolically in the brain. For this purpose, the substances of interest are included in the radioisotope that is injected. This technique has contributed greatly to the study of neurotransmitters and enabled researchers to define the distributions of a number of them. The images produced by PET scans cannot compete with those produced by fMRI scans in terms of resolution, but often provide spectacular color contrasts (the warmer colors represent the more active areas of the brain). With PET scans, the time available for the person to perform each test task is relatively short (less than a minute), because the radiation source decays so rapidly. After each task, the person must wait several minutes for the level of radioactivity emitted to become negligible before another dose can be administered for the next task. The radiation doses that a person receives during a PET session are not very high, but each subject is nevertheless limited to only one session per year. PET scan of the brain of a healthy person.