Fiction and Language

advertisement

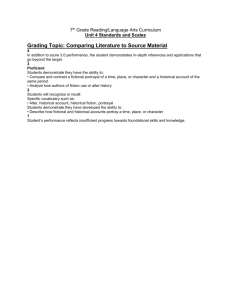

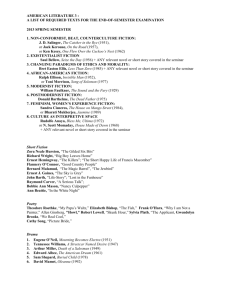

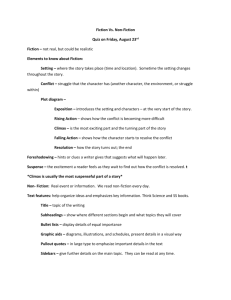

Fiction and Language Convenor: Dr Stacie Friend This module introduces students to some central problems in the philosophy of language posed by fiction. In the first two weeks we focus on the nature of fiction (Topic I). Is the language of fiction characterised by distinctive semantic properties, for example a suspension of reference or truth? Is there a systematic difference in how the author communicates to readers through fiction? We consider various approaches to defining fiction, with special attention to those that define it in terms of the author’s communicative intentions and an invitation to imagine. The second problem concerns the notion of ‘truth in fiction’ (Topic II). What is true-in-afiction – that is, what is the case according to a story – goes beyond what is explicit in the text. We know that Hamlet does not have wings, even if Shakespeare’s play never says so. We know that Lolita is not a willing partner, even if Humbert Humbert’s narration tells us otherwise. How do we infer such fictional truths? And what does it mean to say that something is true-in-fiction? Is ‘truth in fiction’ a special kind of truth? We spend the second two weeks looking at the nature of truth-infiction. We spend the rest of the term examining the issue that has prompted the most interest among philosophers of language: how to understand the names of fictional characters (Topic III). It seems as if we can make true statements about such characters, for instance ‘Hamlet is melancholy’ or ‘Hamlet is a fictional character’, or even ‘Hamlet does not exist’. How can such statements be both meaningful and true if there is no Hamlet? Surely ‘David Cameron is the prime minister’ if and only if the individual in question – the one referred to by ‘David Cameron’ – is in fact the prime minister. But if there is no individual designated by a name, it looks as if statements using that name cannot be either true or false. We begin with some background on reference and ‘empty’ (non-referring) names, then move to consider various accounts designed to address fictional names, including those that postulate fictional entities and those that invoke pretence. Lectures: The lectures for this module will be held in **, on Tuesdays from 6-7pm in the Spring Term. The lecturer is Dr Stacie Friend (s.friend@bbk.ac.uk). Seminars: The seminars for this module will be held in **, on Tuesdays from 7-8pm in the Spring Term. They will be led by the lecturer and by **. Readings: Every week we focus on one reading in the seminar. One of the purposes of the seminar is to help you to understand the reading, so do not worry if you have not fully understood it in advance. However, the lecturer will assume that you have read it, so it is essential that you do so to follow the lecture and participate in discussion. All of the seminar readings are available electronically (most through journals that can be accessed via the library website directly or through the links on Moodle). The ‘additional readings’ listed under each week’s topic will deepen your understanding and help you to get the most out of the module. You are especially advised to cover the additional reading for those topics on which you are planning to write. Most of these readings are also available electronically. Ask the lecturer if you would like any further reading suggestions for essay topics. 1 Essays (BA): This module is assessed by one essay of around 3,000 words. It must be written in response to one of the set questions listed below, except with permission from the module convenor. For details concerning submission of the essay including deadlines, see the BA Handbook. Prior to this assessed essay, you may also write up to two essays during the course, taken from the titles below, and receive feedback on them from your seminar leader. These can be useful practice for your eventual assessed essay. You should submit the first such essay by the first seminar after reading week, and the second by one week after the last seminar of term. [Notes: 1) You are always welcome to submit an essay earlier than these dates; 2) the seminar leader should not be expected to comment on the same essay more than once.] Essay (MA): This module is assessed by one essay of around 3,500 words. It must be written in response to one of the set questions listed below, except with permission from the module convenor. For details concerning submission of the essay including deadlines, see the MA Handbook. Moodle: Electronic copies of course materials are available through Moodle, at http://moodle.bbk.ac.uk. You will need your ITS login name and password to enter. Recommended books: For background on the issues in the philosophy of language, a good introduction is: William Lycan, Philosophy of Language: A Contemporary Introduction, Second Edition (Abingdon: Routledge 2008) The following are classics in the philosophy of fiction that will come up often: Kendall Walton, Mimesis as Make-Believe (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 1990) Gregory Currie, The Nature of Fiction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1990) The following are excellent defences of different positions on reference to fictional characters: Amie Thomasson, Fiction and Metaphysics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1999) Anthony Everett, Nonexistence (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2013) I. THE NATURE OF FICTION Week 1. Theories of fiction Seminar reading: John Searle, ‘The Logical Status of Fictional Discourse’, New Literary History 6 (1975): 319-332 2 Week 2. Fiction and imagining Seminar reading: Gregory Currie, The Nature of Fiction Chapter 1 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1990); we will focus on §1.5 and §§1.7-1.11 Additional readings: Margit Sutrop, ‘Imagination and the Act of Fiction-Making’, Australasian Journal of Philosophy 80 (2002): 332-344 David Davies, Aesthetics and Literature (London: Continuum 2007), Chapter 2 Kathleen Stock, ‘Fictive Utterance and Imagining I’, Aristotelian Society Supplementary Volume 85 (2011): 145-161 Stacie Friend, ‘Fiction as a Genre’, Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society 112 (2012): 179209 Essay questions: Should fiction be defined in terms of the communicative intentions of authors? Which intentions? Can fiction be distinguished from non-fiction in terms of an invitation to imagine? II. TRUTH IN FICTION Week 3. Fictional truths and fictional worlds Seminar reading: David Lewis, ‘Truth in Fiction’ (with postscript), in Philosophical Papers: Volume I (New York: Oxford University Press 1983), 261-280 Week 4. Fictional truth and make-believe Seminar reading: Kendall Walton, Mimesis as Make-Believe Chapter 1 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 1990); we will focus on §§1.2-1.3, 1.5, 1.7 and 1.9-1.10; see also 2.1 Additional readings: Kendall Walton, Mimesis as Make-Believe Chapter 4 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 1990) Gregory Currie, The Nature of Fiction Chapter 2 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1990) Alex Byrne, ‘Truth in Fiction: The Story Continued’, Australasian Journal of Philosophy 71 (1993): 24-35 Richard Hanley, ‘As Good as It Gets: Lewis on Truth in Fiction’, Australasian Journal of Philosophy 82 (2004): 112-128 Essay questions: What does it mean to say that a proposition is ‘true-in-a-fiction’? What is the best account of how we determine whether a proposition is true-in-a-fiction? 3 III. FICTIONAL NAMES Week 5. Reference and Names Seminar reading: Genoveva Martí, ‘Reference’, in Manuel García-Carpintero and Max Kölbel (eds.), The Continuum Companion to the Philosophy of Language (London: Continuum 2012), 106-124 [Reading Week] Week 6. Empty Names Seminar reading: Marga Reimer, ‘The Problem of Empty Names’, Australasian Journal of Philosophy 79 (2001): 491-506 Week 7. Kripke on Names in Fiction Seminar reading: Saul Kripke, Reference and Existence: The John Locke Lectures, excerpts from Lectures I and III (New York: Oxford University Press 2013); unpublished versions of the full lectures are available online Week 8. Realism about Fictional Characters Seminar reading: Peter van Inwagen, ‘Creatures of Fiction’, American Philosophical Quarterly 14 (1977): 299-308 Week 9. The Pretence Theory Seminar reading: Kendall Walton, ‘Fictional Entities’, in Peter McCormick (ed.), The Reasons of Art (Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press 1985), 403-13 Week 10. Comparing the Theories Seminar reading: Amie Thomasson, ‘Speaking of Fictional Characters’, Dialectica 57 (2003): 205223 Additional readings: (i) (ii) (iii) On reference and names generally: Saul Kripke, Naming and Necessity, Lectures I and II (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 1980) William Lycan, Philosophy of Language: A Contemporary Introduction, Second Edition, Chapters 2-4 (Abingdon: Routledge 2008) On empty names including fiction: David Braun, ‘Empty Names’, Noûs 27 (1993): 449-469 Fred Adams, Gary Fuller and Robert Stecker, ‘The Semantics of Fictional Names’, Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 78 (1997): 128-148 Heidi Tiedke, ‘Proper Names and their Fictional Uses’, Australasian Journal of Philosohpy 89 (2011): 707-726 Defending realism about fictional characters: 4 (iv) Amie Thomasson, Fiction and Metaphysics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1999) Amie Thomasson, ‘Fictional Characters and Literary Practices’, British Journal of Aesthetics 43 (2003): 138-157 David Braun, ‘Empty Names, Fictional Names, Mythical Names’, Noûs (2005): 596-631 Critiquing realism about fictional characters: Stacie Friend, ‘Fictional Characters’, Philosophy Compass 2 (2007): 1-16 [provides an overview of the debate between realists and pretence theorists] Anthony Everett, ‘Against Fictional Realism’, Journal of Philosophy 102 (2005): 624-649 Richard Hanley, ‘Much Ado About Nothing: Critical Realism Examined’, Philosophical Studies115 (2003): 123-147 Essay questions What do the names of fictional characters contribute to the truth conditions of sentences in which they appear? Can the direct reference theory account for the meaning and truth of statements containing empty names? Does our discourse about fiction involve pretence? Are there any good reasons to postulate the existence of fictional characters? 5