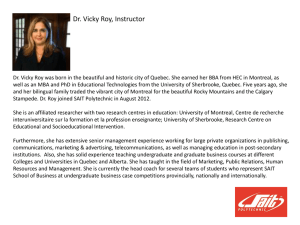

MONTREAL*S EARLY MUSIC HISTORY

advertisement

THE BIRTH OF MONTREAL’S MUSIC INDUSTRY By Dimitri Nasrallah Through the past twenty years, Montreal has once again established its credentials on the international scene as a world-class breeding ground for all manner of forward-thinking musicians. One could argue that the story of Montreal’s contemporary music scene – and here we’ll define contemporary music in a much broader sense, as recordable music – began a century earlier, when the German-born developer of the gramophone Emile Berliner first moved to Montreal in 1897. In 1899, Berliner opened the Berliner Gram-ophone Company of Canada in Montreal. It was the first such record pressing plant in North America. The Berliner Gram-o-phone Company was housed in the Aqueduct Street building of Northern Electric, on the western edges of St-Henri. The Berliner Gram-o-phone Company store at 2315-2316, Sainte-Catherine St. Library and Archives Canada/Music Collection © Public Domain. Courtesy of Oliver Berliner. By the following year, the pressing plant was also marketing records and had opened several record stores around the city to sell their wares. Berliner’s main business involved the manufacturing of foreign-made records for the Canadian market – mostly of the classical, choir, opera, and popular variety – but by 1906, the plant had also opened its own recording studio and was releasing original music. As the operation grew, Berliner Gramophone moved to a larger facility on Lacasse St. in St- Henri – what is today better known as the RCA Victor Building. RCA Victor factory, 1001 Lenoir street, Montreal Courtesy Berliner Musée The presence of the Berliner company in St-Henri meant that touring artists could perform at one of Montreal’s venues and then stay in the city to record their music. As a result, Montreal grew into one of the most important stops on a touring circuit that encompassed North America and parts of Europe. By the end of World War 1, the city had literally hundreds of venues where musicians could perform, not to mention a very healthy repertoire of talented sidemen and backing bands that were ready to support any headlining act that passed through. In 1920, when prohibition took hold in the United States, Montreal transformed into one of the hottest entertainment destinations on the continent. Stepping Out: The Golden Age of Montreal Nightclubs by Nanci Marrelli The rise of a recording and manufacturing industry here, a proximity to both New York and Europe, and the onset of prohibition across the continent set the stage for an era of Montreal’s music scene that still remains unparalleled in its broad public appeal. As archivist Nancy Marrelli notes in her book Stepping Out: The Golden Age of Montreal Nightclubs, “From the 1920s until the early 1950s Montreal had an international reputation as a glamorous wide open city with a lively nightlife.” Fueling the growth of the city’s music industry was the advent of radio. The first Englishlanguage commercial broadcaster in Canada was Montreal’s XWA (which would become CFCF in 1920). For want of entertainment content, CFCF broadcasts often aired live from Montreal’s hotels and clubs. With the rapid proliferation of radio stations across the continent came affiliation and licensing deals, and these arrangements transmitted Montreal’s ample music scene across the continent. As a result, Montreal singers and musicians such as The Melody Kings, Louis Metcalf’s International Band, and Vera Guilaroff rose to international attention. Montreal’s Jazz & the Working Musician There was lots of work to be had for Montreal musicians of the era, and many used the swing and big band stages as a means to a living. But, as Marrelli describes it, “the Montreal club scene was one of complex race, class, and language relations, as well as territorial boundaries.” The ‘uptown’ clubs – which were almost exclusively Englishspeaking – were in what is now considered downtown Montreal, on or close to SteCatherine West. Even though the black community was at the heart of Montreal’s swing and big-band talent pool of instrumentalists, they weren’t welcome in all venues and the musicians’ unions set up for white musicians actively discriminated against them. In uptown clubs and hotels such as the Ritz-Carlton Hotel, Chez Maurice, and the Kit Kat Club, black musicians were welcomed on stage but not in the audiences. The ‘east’ end clubs were clustered around St-Laurent Boulevard and Ste-Catherine, Montreal’s Red Light District, and attracted more of a French audience. In the Red Light District venues like the Monument National, Chinese Paradise and the Stadium Ballroom, it became trendy at times for whites and blacks to co-mingle in the same venues. Calypso singer Lord Caresser at downstairs bar of Rockhead’s Paradise Photo by Louis Jaques, © Library and Archives Canada However, the downtown clubs along St-Antoine Street presented a much different atmosphere. Of closer proximity to the black community, clubs such as Café St-Michel and Rockhead’s Paradise became legendary for their showmanship in large part due to their lax race rules. Here, black and white musicians could perform, dance, and drink together freely. The after-hours nature of a lot of these downtown venues meant that many of the city’s black and white musicians would work at well-paying gigs uptown or in the east end earlier in the evening, collect their pay, and then head down to St-Antoine to improvise, jam, and experiment. As such, the birth of Montreal’s jazz scene – as it came to be distinguished from the more commercial swing and big band of uptown clubs – evolved in these boozy and druggy enclaves under a mantra of ‘anything goes’. It was here that, as jazz historian John Gilmore notes, “for half a century, more jazz was made in Montreal than anywhere else in Canada.” “In Little Burgundy,” internationally renowned jazz pianist Oliver Jones recalls, “there was the St. Michel, the Black Bottom, Rockhead’s, St. Michel and the Latin Quarters. They were all in that area. So a lot of white musicians from what we considered uptown would come down to listen to the wonderful music played by some tremendous black musicians. There were trumpet players like Allan Wellman, Ralph Metcalf, and of course Oscar Peterson, Steep Wade, a wonderful family of saxophonists and piano players, the Sealy Family. They unfortunately were in a era that there wasn’t any recording of them to speak of, and we really missed out on that. Other than Oscar Peterson who was able to bypass all of that and went on to become our greatest jazz artist throughout the world.” Oscar Peterson, 1984 Photo by Harry Palmer, © Library and Archives Canada In the eyes of many jazz musicians, the career of Oscar Peterson was viewed as an exception to the rule. The son of Canadian Pacific Railways porter, Peterson was born in Little Burgundy in 1925, at the height of Montreal’s swing era and his neigbourhood’s creative heyday. A regular of the Montreal club and ballroom circuit of the 40s, his talents were discovered one day as part of a radio broadcast, as Verve label impresario Norman Granz was being driven to the Montreal airport. By 1949, the Montreal pianist was performing at Carnegie Hall. Paul Bley Another Montreal jazz musician to find audiences during the 50s was Paul Bley, a Montrealer born in 1932 whose parents came from Eastern-European Jewish roots and who had stakes in the city’s thriving textiles industry. An important figure in the pioneering of the free and out-jazz schools of performance, Bley first became active in the Montreal jazz scene in the early 50s and founded the Jazz Workshop in Montreal. Maynard Ferguson was another major jazz performer to emerge from that era. Born in Verdun in 1928, by age thirteen he was considered a child prodigy as a horn player and frequently performed with the CBC orchestra. Maynard Ferguson Like all good things, however, Montreal’s jazz heydays would not last, at least not in their original form. Arriving in Montreal in 1952, the television era drastically reduced the numbers of people who went out to see live performances. In October of 1954, Jean Drapeau was elected mayor of Montreal, and shortly thereafter the city underwent a major crackdown on vice and corruption, which included many of the jazz clubs along St-Antoine. By the end of the crackdown, the Ville Marie Expressway cut along StAntoine’s north side, dividing the city in half. With the entertainment & nightlife industry in a stranglehold, many musicians began to leave town. “Throughout the world, people used to call Montreal the Paris of North America, and we produced some wonderful musicians here,” Oliver Jones says. “Others didn’t stay here, they moved to the States. A lot of them went to study in France at the Paris conservatory, and we lost all of those great musicians and they went on to better things. I first came over to the States in ‘61, ‘62.” Biddles promotional T-shirt If many left the province, others stayed and kept jazz alive in the city. Among them was Charlie Biddle, who moved to Montreal in 1948. A significant supporter of the Montreal jazz community, by the late-70s he was organizing festivals of local musicians. In 1981, Biddle also opened a club under his own name, Biddles, which has become a tourist attraction for jazz fans. By the 2000’s, Biddle had received numerous major honours for his lifetime contributions to the Canadian jazz scene. In granting Biddle the Prix CalixaLavallée in 2003, the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste stated, "Without him, Quebecers might not have developed their love for jazz that has made Montreal the host of one of the greatest jazz festivals in the world.” The Post-War Years and Montreal’s Folk Scene By the late-50s, new demographics of music listeners were emerging, and they weren’t interested in chorus lines, big bands, or hotel ballrooms. With television keeping people at home and the old downtown divided by an expressway, the interest for music shifted to college-educated listeners. In place of the masses emerged a more intellectually inclined listener with a worldlier ear, a greater poetic license, and a belief that music could be more than mere entertainment. Many of these musicians and fans came to Montreal in the post-war boom either for McGill University studies or as part of the migration of peoples across the globe – the result of two World Wars. Heidi Fleming, who runs the Fleming Artist Management Group that represents numerous English-speaking Quebecois folk and roots artists, recalls that the growth of the Jewish and Eastern-European communities along the Plateau, Mile End, and Outremont played a role in shaping that new musical generation in Montreal. “After the Holocaust,” she says, sitting in her dining room, “that front room where my office is, the people who lived here, they would rent out that room and people would stay for a month to get re-settled. They were Holocaust survivors.” By the late-50s and early-60s, many of the Jewish community’s younger members drifted toward the jazz clubs and also developed a deep appreciation for pre-war folk and blues music, which was then undergoing a rediscovery period among university students. The ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax was in the process of searching out forgotten musicians of the 1930’s and 40s folk and blues era, and so the words and music of pre-rock n’ roll guitar players such as Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, Jelly Roll Morton, Muddy Waters and many others were quickly gaining new fans all across university campuses The folk scene that developed around the universities in Montreal was inestimably influential on a generation of musicians and music fans. The circuit that developed here around venues in the McGill Ghetto such as the Yellow Door, the Rainbow, the New Penelope Club, and Café André. In the early- to mid-60s, folk singers were performing in numerous coffeehouses throughout the McGill Ghetto and other neighbourhoods as well. Among the many folk singers performing on the stages in the McGill Ghetto was Eastend Montrealer Penny Lang, who built a strong following in the 60s in Quebec and New York coffeehouses. Lang used to perform at Café André six nights a week. Fleming, who now manages Lang, says, “there were line-ups around the block to get in to hear her, because she was quite popular.” At her peak, the folk singer was invited to record a cover of Leonard Cohen’s “Suzanne” and had a fan in Pete Seeger. Cover of Lang’s ‘Gather Honey’ Lang was a notable cult figure of the Montreal folk scene in the 60s, but others such as the Kate and Anna McGarrigle managed to cultivate enormously successful international careers. Raised in Saint-Saveur-des-Monts, Quebec, the McGarrigle sisters had first been taught to play piano by nuns and, like many others, arrived to Montreal in the early 60s in pursuit of university degrees. With perfectly bilingual roots, the sisters pulled in influences from both the British and American folk scenes, as well as the French chanson culture of Edith Piaf. In the mid-60s they often performed as part of the Mountain City Four. The McGarrigle sisters, Kate and Anna © 2009 Kate & Anna McGarrigle Though the McGarrigles’ musical activities didn’t produce international success in the 60s – their first of their ten original albums was released in 1975 – by the early 70s they were already hotly tipped contributors to a growing North American folk scene. Kate McGarrigle had married American singer-songwriter Loudon Wainwright III, and they produced two children together, Rufus Wainwright and Martha Wainwright, both of whom are active on the Montreal and international music scenes today. Certainly no single artist came to define Montreal’s blend of folk music, poetry, and contemporary romanticism more than Leonard Cohen. Like Oscar Peterson, Cohen would outgrow the local scene from which he emerged and become an industry unto himself. Born in Westmount in 1934 to a middle-class Jewish family, by the early 50s Cohen was enrolled at McGill University and was taught to play guitar by Penny Lang. He began publishing volumes of poetry in 1956 and novels in 1963, works that earned him considerable success within Canadian literary circles. In 1967, Cohen moved the United States and, shortly thereafter, he began recording his early folk songs, which would quickly overshadow his more literary work while simultaneously bringing the critical elements of poetry to folk music in a way that broke with the more traditional veins of the genre. Though much of his recording career would develop outside Canada, Cohen’s subject matter was often seen as quintessentially Montréalais. His brand of folk music elevated his home city’s artistic ambitions to mythical levels. Leonard Cohen - performance at salle Wilfrid Pelletier, Dec. 1970 Photo by Peter Brosseau, Library and Archives Canada/PA-170176 © Southam Inc. / Montreal Gazette Professional Jazz and Grassroots Folk: The Rise of a New Networks and Talent If in the 50s and 60s, a generation of jazz and folk musicians was finding that could birth their talents in Quebec but had to leave the province in order to develop substantial careers, by the 70s that perception was beginning to change. Montreal’s small rock scene, though not yet the strong community it is now, had managed to launch the careers of several national and international success stories. The Beau-marks had scored a Canadian and Australian #1 hit with 1960’s Clap Your Hands”. By 1968, local band Influence, featuring Louis McKelvey and Walter Rossi, had released their first album and were picking up a fair amount of critical acclaim across the continent, as did Frank Marino & Mahogany Rush. 1969 saw the birth of Donald Tarlton’ s Aquarius Records, a Montreal rock label that would go on to release many of Canada’s most-loved classic rock in the 70s. In 1971, classic-rockers April Wine had moved to Montreal from Nova Scotia, and were releasing their debut album on Aquarius. Donald Tarlton would go on to become better known as Donald K. Donald the concert promoter, one of the most influential figures in the Canadian rock community. Aquarius records © 2011 Aquarius Records Another such company was Fusion 3, which operated out of Montreal and serviced a number of genres to the rest of Canada. Jim West worked at Fusion 3 in the late-70s and early-80s, after getting into the music business through several years at the Montreal Sam the Record Man store, as well as touring with several rock acts and working shows at the Montreal Forum during the early days of Donald K. Donald brining rock acts to the city. West was part of a growing professional class of industry-experienced personnel that was branching out of the distribution network originally created for rock music. One night in the early 80s, he attended the nightly show at Biddle’s, where Oliver Jones was performing. Biddle had convinced Jones to move back to Quebec after fifteen years abroad, presenting him with the tantalizing opportunity of playing jazz for a living, something that had eluded Jones for his entire career. West was blown away by the music he was hearing. As he recalls, “we had a distribution company that had just been started. Just watching Oliver Jones and seeing the atmosphere and people cheering for it, we decided, well, we have the distribution and we have the know-how, and capturing this fantastic moment would be great.” West decided to start Justin Time Records in 1983, a label that quickly became central to the cultivation of a new generation of Canadian and Quebecois jazz musicians. By 1990, the label had recorded and released some 45 musicians, and had become universally regarded as the main jazz outlet for Canadian talent. Justin Time emerged shortly after Alain Simard and André Ménard’s decided to launch the Montreal International Jazz Festival in 1980. The beginnings were modest: seven concerts and twelve ensembles performing at venues along St-Denis Street, but by 1982 the festival had already launched some outdoor stages and moved jazz out of private clubs and into the public sphere. By 1986, Simard and Ménard had moved there festival to a more central location on Ste-Catherine Street, around the Place des Arts complex. From there it has grown to be one of the biggest festivals of its kind in North America, attracting 1.5 million attendees each year. As a result, the 80s and 90s witnessed a flowering of talent pour into the jazz community to perform, record and teach music, such as Christine Jensen, Joel Miller, the Doxas brother and Steve Amirault. Three of Montreal’s four universities – Concordia, McGill, and the Université de Montreal – have reputable music programs. Others, such as the New York-born jazz vocalist Ranee Lee, had lived here for many years, but began to develop successful recording careers by the late 80s and early 90s. Experimental jazz guitarist Tim Brady was born in Montreal, and returned to the city in 1987 after years in Toronto and London. He spent the next decade working on his internationally renowned chamber group and production company, Bradyworks. Tim Brady - Bang on a Can Marathon - NY, June 27, 2010 Photo by Laurence Labat Given the homegrown venues, record labels, schools, and distribution networks, by the turn of the century a local act starting off in the clubs could land pivotal showcases and then go on to sign a record deal and launch an international career, all without leaving the province. That certainly was the case for Susie Arioli and Jordan Officer, who started off playing the city’s blues clubs in 1996 under the direction of Stephen Barry, a bluesman who also worked alongside guitarists Jimmy James and Steve Rowe. By 1998, Arioli and Officer landed the opportunity of a lifetime opening for Ray Charles on one of the big outdoor stages at the Montreal International Jazz Festival. In 2000, the Susie Arioli Band released their debut album on Justin Time Records. The four albums they have recorded for the label have gone on to become bestsellers in Canada. Susie Arioli If the English-speaking jazz scene in Quebec had managed to find its footing with the establishment of a professional network, some of the folk musicians who’d started off in the late 60s in the McGill Ghetto coffeehouse had, by the 80s, grown into the jazz scene. One such example is Karen Young, a Montreal-born singer and guitarist who scored a minor folk hit at the age of 19 with “Garden of Ursh”. By 1983, she’d undertaken a duo with bassist Michel Donato, a project that ran for seven years and grew into one of her most successful musical ventures. The pair recorded three albums for Justin Time Records. Folk purists still perform at venues such as the Yellow Door, the Golem Coffeehouse, a number of venues along Crescent and Bishop by the downtown Concordia campus, and of course at a number of small folk festivals across the province. The Golem was where Penny Lang, who’d disappeared from the music scene in the 70s, returned to the stage in 1989, in effect relaunching her career from hibernation. From there, Lang connected with a new manager, Heidi Fleming of Fleming Artists Management, and the pair set up the boutique She-Wolf Records to release a prolific run of six Lang albums between 1991 and 1998. These records re-established Lang’s reputation as one of Canada’s iconic folk voices. Connie Kaldor was born in Regina and moved to Montreal following her marriage to music producer and Hart Rouge member, Paul Campagne. Kaldor owns and operates Coyote Entertainment, the label that has released her fourteen albums since 1981. Connie Kaldor Bill Garrett and Sue Lothrop both grew up in rural Quebec and play important roles in the development of the roots genre in Canada. Garret is one of the founders of Borealis Records. One of Borealis’ bright young talents is the Montreal singer-songwriter Katie Moore, who developed her musical skills at the Barfly, the tiny St. Laurent venue that hosts a bluegrass night every Sunday. An active member of the alt-country, folk, and indie-rock communities, Moore also co-hosts a music program on the college-radio station CKUT with Julia Kater, Dara Weiss, and Li’l Andy - another of Barfly’s circle of musicians, born in Wakefield, Quebec. He moved to Montreal in the early 2000’s and began performing soon thereafter with his band, the Karaoke Cowboys. Several albums into a career based loosely in the folk scene but wide-ranging in its absorption of style and instrumentation, the band has worked with the likes of Katie Moore, Jordan Officer, and Angela Desveaux. Katie Moore L’il Andy photo by Caroline Desilets Angela Desveaux photo by Caroline Desilets The traditional end of the spectrum is alive and well too: acts like Rob Lutes, Dan Livingston, Dayle Boyle, Echo Hunters and United Steel Workers of Montreal routinely perform throughout the city’s venues. Of note, Barfly has been very influential in attracting a sizeable young audience to roots, folk, and bluegrass music in recent years. One of the reasons for the venue’s success is Matt Large, a programmer and all-round mentor in the city’s folk and bluegrass community. Large also performs as part of the quintet Notre Dame de Grass and books acts for his production company, Hello Darlin’. In a 2007 interview with the blog Midnight Poutine, Large summed up Montreal’s local scene quite optimistically. “I think we are experiencing a renaissance of sorts in terms of the rare and exceptional quality of local performers which subsequently maintains and propagates an adoring and supportive audience. You have truly gifted singer-songwriters like Katie Moore and Mike O’Brien and staggeringly talented bands like The Lake of Stew and Colin Perry and Blind who are making very authentic, very high calibre music.” Colin Perry and Blind Mike O’Brien Lake of Stew © 2006 F. Yang Photo by Malcolm Bauld These days, over a century after Emile Berliner first brought the recording industry to Montreal, the Montreal indie-rock and electronic communities, born of the same 1980’s “do-it-yourself” mentality, are among the most celebrated in the world. But the jazz and folk scenes that were first to reap the rewards of a Montreal-based music industry are still producing exceptional talents who can still captivate international audiences. The latest to do so is Nikki Yanofsky, the vocal-jazz sensation who became the teenage darling of the Montreal Jazz Festival and performed the Canadian national anthem at the 2010 Vancouver Olympics. Surely, there will be more to come. MONTREAL IN RECORDS The local swing, jazz and folk scenes have all experienced some unforgettable moments on record. Louis Metcalf – I’ve Got the Peace Brother Blues (1966) Metcalf was a Montreal swing sensation in the 20s and forgotten by the 40s, but he kept performing and perfecting his craft in his hometown all his life. Captured here in a rare 1966 recording. Leonard Cohen – Songs of Leonard Cohen (1968) Born in Westmount and a national literary sensation by the mid-60s, Cohen’s debut album came out in 1968 and has ranked firmly among his best work ever since. Featuring the much-loved “Suzanne” and “So Long, Marianne”. Oscar Peterson – The Trio (1973) Discovered by Verve Records impresario Norman Granz during a Montreal radio broadcast, Peterson went on to become the most famous Canadian jazz player ever. The Trio described in the title of this 1973 recording features guitarist Joe Pass and bassist Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen. The McGarrigle Sisters – Kate & Anna McGarrigle (1975) After a decade honing their sound within the vibrant Montreal folk scene, sister Kate and Anna McGarrigle released this classic debut in 1975. It was the most critically acclaimed album of their career, Oliver Jones – The Lights of Burgundy (1985) After decades of supporting himself as a pop conductor in the United States, Jones turned to jazz professionally in 1983 when he signed to Montreal’s Justin Time Records. This 1985 album was his sophomore effort for the label, and an ode to the neighbourhood of his birth. Tim Brady – Imaginary Guitars (1995) Though more a fusion of the avant-garde ends of rock, jazz, and classical music, Brady moved back to Montreal in 1987 and perfected his unique guitarwork through an acclaimed series of projects loosely grouped under the title Bradyworks. Penny Lang – Live at the Yellow Door (1998) The cult sensation of the Montreal folk scene in the 60s, Lang faded from the limelight as alcoholism and other demons took over her life. But by the 90s, she had made a successful comeback and was considered one of the pioneers of the genre. This 1998 recording has Lang performing in the venue where she got her start, Susie Arioli Swing Band featuring Jordan Officer – Pennies from Heaven (2002) A Montreal success story, Arioli and Officer hit the jackpot when they landed an opening slot for Ray Charles on the free stage of the Montreal International Jazz Festival. Soon after, they signed to Justin Time Records. Ranee Lee – Lives Upstairs (2009) A New Yorker by birth, Lee has made Montreal her home for much of her adult life. This 2009 recording catches her at the marquee Montreal jazz club, Upstairs, performing classic standards for an intimate audience. Lake of Stew – Sweet as Pie (2009) Eclectic and adventurous, Lake of Stew are one of the many new talents rising out of the folk renaissance centred around the Barfly. This second album in truly a Montreal affair, released on the city’s Dare to Care Records