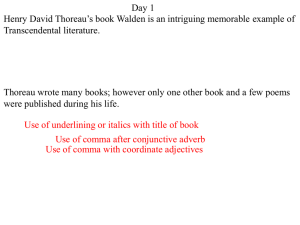

Henry David Thoreau

advertisement

Name: _____________________________________________________ AP Lang “Where I Lived, and What I Lived For” Henry David Thoreau 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Through the first paragraph, what does Thoreau declare as his higher purpose? Explain the distinctions he makes in paragraph 1. Cite and explain the antithesis in the first paragraph. What is the effect of the similes in paragraph 2? Explain the nature and effect of the extended metaphor in the second paragraph. What effect does Thoreau create with his repetitions? Cite several examples. Explain the paradox Thoreau develops concerning the railroad in paragraph 2. Paragraph 3 begins with a rhetorical question. How effectively does the rest of the paragraph imply an answer? 9. Discuss the meaning of the phrase “starved before we are hungry,” near the beginning of paragraph 3. 10. Paragraph 4 delivers a strong statement both now and in Thoreau’s time. Compare its probable rhetorical effect then and now. 11. Sometimes even the slightest stylistic feature can work as a rhetorical strategy. Discuss the effect of the alliterative phrase “freshet and frost and fire” in paragraph 7. 12. In his concluding paragraph, Thoreau develops two metaphors regarding tine and intellect. Cite them and discuss their effect. Summary He explains that he chose Walden Pond because he "wished to live deliberately," to simplify everything in his life to the barest of necessities so that he could really live. Although he lives within a mile-and-a-half from Concord and it may be within walking distance of civilization, to him it's an unexplored corner of the universe. Nowadays, the world moves too quickly; he wants to slow down and really enjoy life. To understand what is wonderful and sublime about life, you don't have to go off into distant corners of the earth. The sublime is right here, right now, in the everyday. Newspapers never tell us anything new, according to Thoreau. He wants to dig "through the mud and slush of opinion, and prejudice, and tradition, and delusion, and appearance" and get to reality. Another summary Having provided an example of how his life became fresh and vitally alive, the narrator turns to his readers and asks why they continue to live as drably as they do. He wonders why men persist in living "meanly, like ants" when life can be a joyful celebration. He complains that "our life is frittered away by detail," and that most men's personalities are uncomfortably split into many opposing parts. Holding up his own example of spiritual wholeness, he offers his readers the remedy for spiritual disintegration that he discovered and announced in "Economy": "Simplicity, simplicity, simplicity! I say, let your affairs be as two or three, and not a hundred or a thousand. . . . Simplify, simplify." Moreover, he declares that we should push aside all of the trivialities of life and immediately get down to the real, genuine concerns of life. For example, we should quit wasting our time reading the worthless, repetitive gossip that fills the daily newspapers and seek out the real truths of existence. The narrator was able to do this, and we watch him as he continues his "burrowing" toward truth; "I would mine and burrow my way through these hills. I think that the richest vein is somewhere hereabouts." As Walden progresses, we shall see the spiritual riches that he "mined" from living at Walden Pond. And Another Thoreau says, "I went to the woods to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I coudl not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived." He wants to know life's true meanness or true sublimeness and give a true account of it, not be like men who live in uncertainty about the meaning of life. Here, he urges "Simplicity! Simplicity! Simplicity!," telling people to simplify their affairs and arguing that socalled "improvements" like railroads, which make life too fast and superficial. Here, with a play on words, he compares the "sleepers" on the railroad to the men who work on it, who are "sleepers" because they are not awake enough to appreciate life. Thoreau wonders why people need to live with such hurry. He thinks that if he rang the bell for a fire in town, people would come rushing from miles around, not to save the burning property but really to watch the fire. Thoreau also sees no point in reading the newspaper, in which the same stories are told time and again with new details, and considers it gossip. He says he has never gotten anything worth the postage from the post office either. Men should observe only reality, which is far more fabulous than the illusions they think are truth. Instead of perceiving unhurried, men give in to the illusion of routine and habit. New Englanders lead "mean lives" because their "vision does not penetrate the surface of things." If they were to truly describe any building in the town, no one would recognize it. Rather than thinking the truth is somewhere far away and distant in time, recognize that "God himself culminates in the present moment." Thoreau urges everyone to "spend one day deliberately as Nature" and to push through all outer appearance and poetry and philosophy and religion all the way down to the hard ground of reality, to find out if it is life or death and really feel it. Considering the shortness of time in the course of eternity, he regrets the way his intellect has separated him from reality and hopes his instinct will lead him to it. Some interesting biographical information about Thoreau: He was a significant abolitionist. He delivered lectures that attacked the Fugitive Slave Law, praised the writings of Wendell Phillips, and defended abolitionist John Brown. His philosophy of nonviolent resistance influenced the political thoughts of such later figures as Leo Tolstoy, Mahatma Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, Jr. At Walden Pond, he actually lived within walking distance from a store. Though most people envision Thoreau as living in some remote woodland during his Walden experiment, he actually lived only a mile and a half from his house. In fact, his record of his time “alone in the wilderness” detailed more than a few trips into Concord Center for supplies. Richard Zacks offers this rather critical perspective: “Thoreau’s Walden, or Life in the Woods deserves its status as a great American book, but let it be known that Nature Boy went home on weekends to raid the family cookie jar. While living the simple life in the woods, Thoreau walked into nearby Concord, Massachusetts, almost every day. And his mom, who lived less than two miles away, delivered goodie baskets filled with meals, pies and doughnuts every Saturday.” The Thoreaus went to Harvard and organized the first student protest. Thoreau’s grandpa, Asa Dunbar, began the first-ever college protest when the butter at the dining hall tasted bad. To begin “The Great Butter Rebellion” (this is seriously what it is called), Dunbar jumped on his chair and exclaimed, “Behold, our butter stinketh! – give us therefore, butter that stinketh not.” Thoreau continued his family’s tradition of protest when he refused to pay the $5 fee for a diploma. He objected to the fact that it was made of sheepskin. He was fired from his teaching position because he refused to hit kids. The schools in Concord, Massachusetts, apparently mandated that teachers use corporal punishment in their classrooms. ***** There will be a nine question MCquiz on the first three paragraphs of the selection.