1NC “Fuck” K - NDCA National Argument List

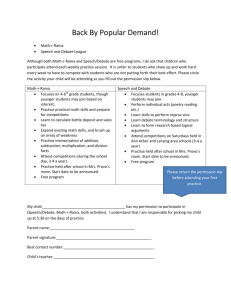

advertisement