Comment 7: Livestock Grazing

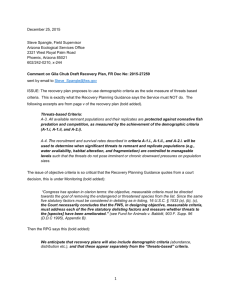

advertisement

December 25, 2015 Steve Spangle, Field Supervisor Arizona Ecological Services Office 2321 West Royal Palm Road Phoenix, Arizona 85021 602/242-0210, x-244 Comment on Gila Chub Draft Recovery Plan, FR Doc No: 2015-27259 sent by email to Steve_Spangle@fws.gov ISSUE: Livestock grazing is not accurately represented in the recovery plan. The recovery plan fails to present the conclusions about livestock grazing that are in the Final Rule. In the Final Rule as published in the Federal Register, Nov 2, 2005, page 66680 (bold added): Livestock grazing administered by either the FS or BLM occurs in most of the streams and watersheds containing Gila chub. We have completed four formal conferences on the effects of livestock grazing on Gila chub. All four conferences found that livestock grazing resulted in adverse effects to Gila chub and its habitat (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2005b), but is not likely to jeopardize the species or result in destruction or adverse modification of critical habitat. At the bottom of page 66688, the Final Rule says this: (bold added) Livestock grazing is only a threat to Gila chub if not properly managed. Proper management may include the use of fencing, rest rotation grazing systems, and other improvements to allotments such as new water tanks. The failure of the recovery plan to present these statements has major consequences. Livestock grazing is not inherently incompatible with the Gila chub and can be managed so it is not a significant threat to the critical habitat. The recovery plan’s nonspecific overemphasis of livestock grazing as a threat will confuse and misdirect recovery efforts and misinform the USFS and BLM. Ill-considered restrictions on livestock grazing imposed by the USFS and BLM can create unnecessary hardships and costs, while not providing significant benefits to the Gila chub. These costs fall on the agencies involved as well as livestock grazers. The EA for Critical Habitat, page 71 (bold added): 3.9.2.2 Proposed Rule Alternative Compared to No Action, the Proposed Rule Alternative would result in 1) a small, but unknown, increase in the number of additional new and reinitiated section 7 consultations for livestock grazing based solely on the presence of designated critical habitat, and 2) the addition of an adverse modification of critical habitat analysis to section 7 consultations for Gila chub in critical habitat. The areas most likely to be affected are those not occupied by Gila chub but designated as Gila chub critical habitat. The additional consultations would increase administrative costs to the Service, the action agencies, and any project proponent involved in the consultation process. 1 Identifying Less Significant Threats The Recovery Plan Guidance (RPG, Box 3.2.2-2, Prompt Sheet for Threats Assessment) tells the Service to identify which threats are not significant: Did the listing rule include threats that may not be significant or contribute significantly to the species status as threatened or endangered? For the Gila chub, the Final Listing Rule identified livestock grazing as not likely to jeopardize the species, and therefore it did not contribute significantly to the species status of endangered. But the recovery plan fails to acknowledge that. Page 51 is an example of misleading information because the recovery plan fails to identify livestock grazing as a less significant threat. In some places the recovery plan makes it clear that the single biggest threat to the Gila chub is nonnative species. But this becomes confused because other statements conflict with that, or are vague and non-specific. Statements about threats are inconsistent across the recovery plan. The page 51 statement lists threats, and includes the primary threat of nonnative fishes along with the far less significant threat of livestock grazing. But the statement gives no clarification if one threat is greater or lesser. The reader is left with the impression that all of these threats are equally significant (“These continuing uses…”) and that is simply not true. The statement at page 51 is careless and inaccurate. (bold added) Anthropogenic development Most if not all stream habitats within the greater Gila River basin have been significantly altered as a result of human land uses such as road construction, livestock grazing, silvicultural practices, dam emplacement, water diversion, groundwater pumping, and introduction of nonnative fishes. These continuing uses largely caused the endangerment of Gila chub, and thus the potential for recovery of the species is greatly diminished as long as these practices continue unabated. The Narrative Outline for Recovery Action at page 63 does not include livestock grazing as a primary threat, or even a secondary threat. This statutory requirement is stated in the RPG, under 5.1.8.3 Recovery Criteria (bold added): Developing recovery criteria that are both objective and measurable is a statutory requirement in the ESA for recovery plans and a useful exercise in terms of planning. The ESA states that each recovery plan shall incorporate, to the maximum extent practicable, threats, recovery may be possible in multiple states, e.g., a species might be able to tolerate a continuing level of one threat if another threat has been eliminated. The point here is to identify lesser threats the species “can live with”, if the more severe threats were controlled. Grazing is a threat the Gila chub can live with. The chub had been living with grazing for decades before the nonnatives came onto the scene. 2 Since the recovery plan has not examined these relationships, we constructed a simple chart to look at the correlation between Gila chub and grazing. We compared Table I.3 of chub population size (page 14) to Table 1.4 Matrix of threats (p.19). From Table 1.3, we took the places with a large chub population. Then we check Table 1.4 to see if grazing is present. We find nine localities with large populations and six of these have livestock grazing present. Apparently the Gila chub persist successfully in areas that have livestock grazing. At the least, there is no negative correlation between grazing and chub population size. Locality Population Size Grazing Hot Springs/ Bass Canyon/ Double R/Wildcat L no Redfield Cyn L no Cienaga Ck L no Blue River (San Carlos) L yes Bonita Ck L yes Dix Ck L yes Harden Cienaga (S.F. River) L yes Turkey Ck, NM L yes Spring Ck (Verde) L yes Grazing has been established in the area for well over one hundred years. If anything, the numbers of livestock the USFS and BLM allow to graze has decreased in recent decades because of reduced forage due to drought and high utilization by the overpopulated elk. The decline of the chub is relatively recent, and corresponds to the nonnatives. The RPG statement above tells the Service it should address whether the Gila chub could tolerate livestock grazing, if the primary threat of nonnatives were eliminated. To repeat, the Final Rule calls livestock grazing a threat but not one that jeopardizes the species. The recovery plan does not ask or answer this critical question. Overgrazing The recovery plan fails to provide accurate information when it asserts that overgrazing is a current threat, on page 63 (bold added): Secondary threats include more long-term effects to habitat and ecosystem processes via overgrazing by domestic livestock of the uplands or riparian corridor, excessive silvicultural practices that destabilize soils, road alignments along or crossing the stream, etc. And at page 16 (bold added): 3 A. The Present or Threatened Destruction, Modification, or Curtailment of Its Habitat or Range Habitat loss due to water diversions, groundwater pumping, impoundments, dams, channelization, improperly managed livestock grazing, agriculture, mining, road building, and residential development are all recorded as historical and ongoing activities that have contributed to the decline of Gila chub populations (Weedman et al. 1996, Propst 1999). Overgrazing has been inserted in the Narrative Outline for Recovery Action as a secondary threat, p. 63 (bold added): 1. Protect and manage remnant populations and their habitats 1.1. Identify threats to each remnant population Primary, immediate threats to a population include desiccation of habitat via natural (e.g., drought or climate change) or manmade (e.g., diversion or excessive groundwater pumping) influences, presence of or threat of invasion by problematic nonnative fishes or other nonnative aquatic organisms (including parasites and pathogens), or other destructive threats to habitat (e.g., channelization, dam construction, wildfire, phreatophyte removal, etc.). Secondary threats include more long-term effects to habitat and ecosystem processes via overgrazing by domestic livestock of the uplands or riparian corridor, excessive silvicultural practices that destabilize soils, road alignments along or crossing the stream, etc. We note that overgrazing is listed as a secondary threat, but livestock grazing in general is NOT listed as either a primary or secondary threat. The statements of overgrazing are in error. If the Service maintains that the Gila chub is currently impacted by overgrazing, it is accusing the USFS and BLM of grossly failing to properly manage the lands. The Gila chub lives mostly on federal lands where grazing is totally controlled by the USFS and BLM. This statement is at page 29: Gila chub primarily occurs on Federal lands managed by the USFS and the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM). That is echoed by this statement in the Final Rule, page 66680 cited above: Livestock grazing administered by either the FS or BLM occurs in most of the streams and watersheds containing Gila chub. These statements on overgrazing should be corrected to state that the USFS and BLM manage the land to prevent overgrazing and have done so for decades. REMEDY: The remedy is to answer the questions raised in this comment, and to make corrections to the misstatements in the recovery plan, to make the statements about the threats concise and consistent and to identify that livestock grazing is a lesser threat that does not jeopardize the species or result in destruction or adverse modification to critical habitat. Thank you for the opportunity to comment, 4