Division I: Humanities

advertisement

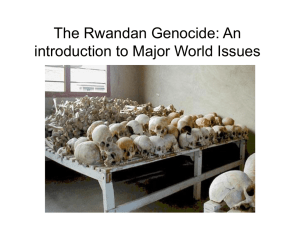

Name: _________________________ Date: _________________ Section: 12.1 12.2 Modern World History Classwork: Defining Genocide Do Now Use your winter break homework to write a three-sentence summary of each of the following genocides. (Skip Bosnia or Cambodia, if necessary.) Armenia: _____________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ The Holocaust: _______________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Rwanda: ______________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Bosnia: ________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Cambodia: ____________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Reading: Defining Genocide As we read, underline or highlight any information that helps you answer the question: According to the United Nations, what are the defining characteristics of genocide, and how is it different from mass murder? As we read, make a list of these characteristics in the margins. Source: BBC News, “Analysis: Defining Genocide,” August 27, 2010, retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-11108059. Genocide is understood by most to be the gravest crime against humanity it is possible to commit. It is the mass extermination of a whole group of people, an attempt to destroy an entire group and wipe them out of existence. But at the heart of this simple idea is a complicated tangle of legal definitions. This has led to conflicting views on when a mass killing, or forced movement, of people can be called genocide. There are people who say that there was only one genocide during the last century. Others say there were at least three, possibly more. What is genocide and when can that term be applied? UN definition The term was coined in 1943 by the Jewish-Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin who combined the Greek word "genos" (race or tribe) with the Latin word "cide" (to kill). After witnessing the horrors of the Holocaust - in which every member of his family except his brother and himself was killed - Dr Lemkin campaigned to have genocide recognised as a crime under international law. His efforts gave way to the adoption of the UN Convention on Genocide in December 1948, which came into effect in January 1951. Article Two of the convention defines genocide as "any of the following acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such": Killing members of the group Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group The convention also imposes a general duty on states that are signatories to "prevent and to punish" genocide. Since its adoption, the UN treaty has come under fire from different sides, mostly by people frustrated with the difficulty of applying it to different cases. Classwork: Is It Genocide? Criteria 1) 2) 3) Methods: (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) Armenia Germany Rwanda Classwork: Is It Genocide? (continued) Criteria 1) 2) 3) Methods: (a) (b) (c) (d) (e) Bosnia Cambodia Modern World History HW 4.1: The Roots of Genocide in Rwanda Instructions Carefully read the following text. (Yes, it’s long!) As you read, underline, highlight, or otherwise annotate in any way that helps you make sense of the text. Then, in your own words, answer the following questions in complete sentences on a separate sheet of paper: 1. What was the origin of the terms “Tutsi” and “Hutu”? 2. Why did Tutsi and Hutu people become more distinctive over time? 3. Who were the Twa? What social status did they have before the arrival of Europeans? 4. How did the arrival of German and Belgian colonialism affect the power of government in Rwanda? How might ordinary Rwandans feel about these changes? 5. What did European colonizers believe about the differences between Tutsi, Hutu, and Twa in Rwanda? Which group did the Europeans consider superior? 6. Why did Europeans assume that the Tutsi had created the Rwandan government? How did this assumption influence the way they governed Rwanda? 7. How did the colonizers, with Tutsi help, rewrite Rwandan history? How did this retelling of history change relationships between Tutsi and Hutu? 8. Describe the system of registration that the Belgian colonizers established in the 1930s. How did this affect the meaning of race/ethnicity in Rwanda? 9. How did the Belgians change their treatment of the Hutu in the 1950s? Why? Source: Adapted from Human Rights Watch, Leave None to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda, March 1999. Retrieved from http://www.hrw.org/legacy/reports/1999/rwanda/. Rwandans take history seriously. Hutu who killed Tutsi did so for many reasons, but beneath the individual motivations lay a common fear rooted in firmly held but mistaken ideas of the Rwandan past. Organizers of the genocide, who had themselves grown up with these distortions of history, skillfully exploited misconceptions about who the Tutsi were, where they had come from, and what they had done in the past. From these elements, they fueled the fear and hatred that made genocide imaginable. To understand how some Rwandans could carry out a genocide and how the rest of the world could turn away from it, we must begin with history. The Meaning of “Hutu,” “Tutsi,” and “Twa” Forerunners of the people who are now known as Hutu and Tutsi settled Rwanda over a period of two thousand years. They developed a single and highly sophisticated language, Kinyarwanda, crafted a common set of religious and philosophical beliefs, and created a culture which valued song, dance, poetry, and rhetoric. They celebrated the same heroes: even during the genocide, the killers and their intended victims sang of some of the same leaders from the Rwandan past. As the Rwandan state grew in strength and sophistication, the governing elite became more clearly defined and its members, like powerful people in most societies, began to think of themselves as superior to ordinary people. The word “Tutsi,” which apparently first described the status of an individual—a person rich in cattle—became the term that referred to the elite group as a whole and the word “Hutu”—meaning originally a subordinate or follower of a more powerful person—came to refer to the mass of the ordinary people. The identification of Tutsi pastoralists [people who raise animals] as power-holders and of Hutu cultivators [farmers] as subjects was becoming general when Europeans first arrived in Rwanda at the turn of the century, but it was not yet completely fixed throughout the country. Most people married within the occupational group in which they had been raised. This practice created a shared gene pool within each group, which meant that over generations pastoralists came to look more like other pastoralists—tall, thin and narrow-featured—and cultivators like other cultivators—shorter, stronger, and with broader features. Although it was not usual, Hutu and Tutsi sometimes intermarried. The practice declined in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as the gap widened between Tutsi elite and Hutu commoners, but rose again after Tutsi lost power in the 1959 revolution. With the increase in mixed marriages in recent decades, it has become more difficult to know a person’s group affiliation simply by looking at him or her. Some people look both “Hutu” and “Tutsi” at the same time. In addition, some people who exhibit the traits characteristic of one group might in fact belong to the other because children of mixed marriages took the category of their fathers, but might actually look like their mothers. During the genocide some persons who were legally Hutu were killed as Tutsi because they looked Tutsi. The Twa, a people clearly differentiated from Hutu and Tutsi, formed the smallest component of the Rwandan population, approximately 1 percent of the total before the genocide. Originally forest dwellers who lived by hunting and gathering, Twa had in recent decades moved closer to Hutu and Tutsi, working as potters, laborers, or servants. Physically distinguishable by such features as their smaller size, Twa also used to speak a distinctive form of Kinyarwanda. While the boundary between Hutu and Tutsi was flexible and permeable before the colonial era, that separating the Twa from both groups was far more rigid. Hutu and Tutsi shunned marriage with Twa and used to refuse even to share food or drink with them. During the genocide, some Twa were killed and others became killers. Colonial Changes in the Political System The Germans, who established a colonial administration in Rwanda at the turn of the century, and the Belgians who replaced them after the First World War, ended the occasional open warfare that had taken place within Rwanda and between Rwanda and its neighbors. Both Germans and Belgians sought to rule Rwanda with the least cost and the most profit. In the 1920s, the Belgians began to alter the Rwandan state in the name of administrative efficiency. Always professing an intention to keep the essential elements of the system intact, they eliminated the competing hierarchies and regrouped the units of administration into “chiefdoms” and “sub-chiefdoms” of uniform size, allowed chiefs and sub-chiefs to exercise more power over the people, and made it harder for the weak to escape repressive officials. At the same time, the Belgians decreed that Tutsi alone should be officials. They systematically removed Hutu from positions of power and they excluded them from higher education, which was meant mostly as preparation for careers in the administration. Thus they imposed a Tutsi monopoly of public life not just for the 1920s and 1930s, but for the next generation as well. The only Hutu to escape relegation to the laboring masses were those few permitted to study in religious seminaries. The Transformation of “Hutu” and “Tutsi” By assuring a Tutsi monopoly of power, the Belgians set the stage for future conflict in Rwanda. Such was not their intent. They were not implementing a “divide and rule” strategy so much as they were just putting into effect the racist convictions common to most early twentieth century Europeans. They believed Tutsi, Hutu, and Twa were three distinct, long-existent and internally coherent blocks of people, the local representatives of three major population groups, the Ethiopid, Bantu and Pygmoid. Unclear whether these were races, tribes, or language groups, the Europeans were nonetheless certain that the Tutsi were superior to the Hutu and the Hutu superior to the Twa—just as they knew themselves to be superior to all three. Because Europeans thought that the Tutsi looked more like themselves than did other Rwandans, they found it reasonable to suppose them closer to Europeans in the evolutionary hierarchy and hence closer to them in ability. Believing the Tutsi to be more capable, they found it logical for the Tutsi to rule Hutu and Twa just as it was reasonable for Europeans to rule Africans. Unaware of the “Hutu” contribution to building Rwanda, the Europeans saw only that the ruler of this impressive state and many of his immediate entourage were Tutsi, which led them to assume that the complex institutions had been created exclusively by Tutsi. Not surprisingly, Tutsi welcomed these ideas about their superiority, which coincided with their own beliefs. As they became aware of European favoritism for the Tutsi in the late 1920s and early 1930s, Rwandan poets and historians saw the advantage in providing information that would reinforce this predisposition. They supplied data to the European clergy and academics who produced the first written histories of Rwanda. The collaboration resulted in a sophisticated and convincing but inaccurate history that simultaneously served Tutsi interests and validated European assumptions. According to these accounts, the Twa hunters and gatherers were the first and indigenous residents of the area. The somewhat more advanced Hutu cultivators then arrived to clear the forest and displace the Twa. Next, the capable, if ruthless, Tutsi descended from the north and used their superior political and military abilities to conquer the far more numerous but less intelligent Hutu. This mythical history drew on and made concrete the “Hamitic hypothesis,” the then-fashionable theory that a superior, “Caucasoid” race from northeastern Africa was responsible for all signs of true civilization in “Black” Africa. This distorted version of the past told more about the intellectual atmosphere of Europe in the 1920s than about the early history of Rwanda. Packaged in Europe, it was returned to Rwanda where it was disseminated through the schools and seminaries. So great was Rwandan respect for European education that this faulty history was accepted by the Hutu, who stood to suffer from it, as well as by the Tutsi who helped to create it and were bound to profit from it. People of both groups learned to think of the Tutsi as the winners and the Hutu as the losers in every great contest in Rwandan history. The polished product of early Rwando-European collaboration stood unchallenged until the 1960s. Once the Belgians had decided to limit administrative posts and higher education to the Tutsi, they were faced with the challenge of deciding exactly who was Tutsi. Physical characteristics identified some, but not for all. Because group affiliation was supposedly inherited, genealogy [the study of family roots] provided the best guide to a person’s status, but tracing genealogies was time-consuming and could also be inaccurate, given that individuals could change category as their fortunes rose or fell. The Belgians decided that the most efficient procedure was simply to register everyone, noting their group affiliation in writing, once and for all. All Rwandans born subsequently would also be registered as Tutsi, Hutu, or Twa at the time of their birth. The system was put into effect in the 1930s, with each Rwandan asked to declare his group identity. Some 15 percent of the population declared themselves Tutsi, approximately 84 percent said they were Hutu, and the remaining 1 percent said they were Twa. This information was entered into records at the local government office and indicated on identity cards which adult Rwandans were then obliged to carry. The establishment of written registration did not completely end changes in group affiliation. In this early period Hutu who discovered the advantages of being Tutsi sometimes managed to become Tutsi even after the records had been established, just as others more recently have found ways to erase their Tutsi origins. But with official population registration, changing groups became more difficult. The very recording of the ethnic groups in written form enhanced their importance and changed their character. No longer flexible and amorphous, the categories became so rigid and permanent that some contemporary Europeans began referring to them as “castes” [fixed, hereditary social classes]. The ruling elite, most influenced by European ideas and the immediate beneficiaries of sharper demarcation [distinction] from other Rwandans, increasingly stressed their separateness and their presumed superiority. Meanwhile Hutu, officially excluded from power, began to experience the solidarity of the oppressed. The Hutu Revolution Belgium continued its support for the Tutsi until the 1950s. Then, faced with the end of colonial rule and with pressure from the United Nations, which supervised the administration of Rwanda under the trusteeship system, the colonial administrators began to increase possibilities for Hutu to participate in public life. They named several Hutu to responsible positions in the administration, they began to admit more Hutu into secondary schools, and they conducted limited elections for advisory government councils. Hardly revolutionary, the changes were enough to frighten the Tutsi, yet not enough to satisfy the Hutu. With independence approaching, conservative Tutsi hoped to oust the Belgians before majority rule was installed. Radical Hutu, on the contrary, hoped to gain control of the political system before the colonialists withdrew. Name: _________________________ Date: _________________ Section: 12.1 12.2 Exit Ticket: Defining Genocide In at least 5 complete sentences, assess the United Nations definition of genocide, using your knowledge of different case studies of genocide. Is it too broad? Too narrow? Just right? What are some possible problems with implementing this definition? _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________________________________________________