Terms of Reference - Cambridge Multifamily Project

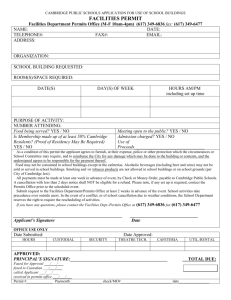

advertisement