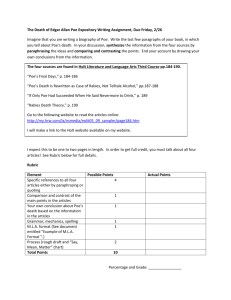

Ernest Hemingway Biography

Author (1899–1961)

Nobel Prize winner Ernest Hemingway is seen as one of the great

American 20th century novelists, and is known for works like A Farewell

to Arms and The Old Man and the Sea.

Synopsis

Born on July 21, 1899, in Cicero (now in Oak Park), Illinois, Ernest

Hemingway served in World War I and worked in journalism before

publishing his story collection In Our Time. He was renowned for novels

like The Sun Also Rises, A Farewell to Arms, For Whom the Bell Tolls,

and The Old Man and the Sea, which won the 1953 Pulitzer. In 1954,

Hemingway won the Nobel Prize. He committed suicide on July 2, 1961,

in Ketchum, Idaho.

Early Life and Career

Ernest Miller Hemingway was born on July 21, 1899, in Cicero (now in

Oak Park), Illinois. Clarence and Grace Hemingway raised their son in

this conservative suburb of Chicago, but the family also spent a great deal

of time in northern Michigan, where they had a cabin. It was there that

the future sportsman learned to hunt, fish and appreciate the outdoors.

In high school, Hemingway worked on his school newspaper, Trapeze

and Tabula, writing primarily about sports. Immediately after graduation,

the budding journalist went to work for the Kansas City Star, gaining

experience that would later influence his distinctively stripped-down

prose style.

He once said, "On the Star you were forced to learn to write a simple

declarative sentence. This is useful to anyone. Newspaper work will not

harm a young writer and could help him if he gets out of it in time."

Military Experience

In 1918, Hemingway went overseas to serve in World War I as an

ambulance driver in the Italian Army. For his service, he was awarded the

Italian Silver Medal of Bravery, but soon sustained injuries that landed

him in a hospital in Milan.

There he met a nurse named Agnes von Kurowsky, who soon accepted

his proposal of marriage, but later left him for another man. This

devastated the young writer but provided fodder for his works "A Very

Short Story" and, more famously, A Farewell to Arms.

Still nursing his injury and recovering from the brutalities of war at the

young age of 20, he returned to the United States and spent time in

northern Michigan before taking a job at the Toronto Star.

It was in Chicago that Hemingway met Hadley Richardson, the woman

who would become his first wife. The couple married and quickly moved

to Paris, where Hemingway worked as a foreign correspondent for

the Star.

Life in Europe

In Paris, Hemingway soon became a key part of what Gertrude Stein

would famously call "The Lost Generation." With Stein as his mentor,

Hemingway made the acquaintance of many of the great writers and

artists of his generation, such as F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound, Pablo

Picasso and James Joyce. In 1923, Hemingway and Hadley had a son,

John Hadley Nicanor Hemingway. By this time the writer had also begun

frequenting the famous Festival of San Fermin in Pamplona, Spain.

In 1925, the couple, joining a group of British and American expatriates,

took a trip to the festival that would later provided the basis of

Hemingway's first novel, The Sun Also Rises. The novel is widely

considered Hemingway's greatest work, artfully examining the postwar

disillusionment of his generation.

Soon after the publication of The Sun Also Rises, Hemingway and Hadley

divorced, due in part to his affair with a woman named Pauline Pfeiffer,

who would become Hemingway's second wife shortly after his divorce

from Hadley was finalized. The author continued to work on his book of

short stories, Men Without Women.

Critical Acclaim

Soon, Pauline became pregnant and the couple decided to move back to

America. After the birth of their son Patrick Hemingway in 1928, they

settled in Key West, Florida, but summered in Wyoming. During this

time, Hemingway finished his celebrated World War I novel A Farewell

to Arms, securing his lasting place in the literary canon.

When he wasn't writing, Hemingway spent much of the 1930s chasing

adventure: big-game hunting in Africa, bullfighting in Spain, deep-sea

fishing in Florida. While reporting on the Spanish Civil War in 1937,

Hemingway met a fellow war correspondent named Martha Gellhorn

(soon to become wife number three) and gathered material for his next

novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls, which would eventually be nominated

for the Pulitzer Prize.

Almost predictably, his marriage to Pauline Pfeiffer deteriorated and the

couple divorced. Gellhorn and Hemingway married soon after and

purchased a farm near Havana, Cuba, which would serve as their winter

residence.

When the United States entered World War II in 1941, Hemingway

served as a correspondent and was present at several of the war's key

moments, including the D-Day landing. Toward the end of the war,

Hemingway met another war correspondent, Mary Welsh, whom he

would later marry after divorcing Martha Gellhorn.

In 1951, Hemingway wrote The Old Man and the Sea, which would

become perhaps his most famous book, finally winning him the Pulitzer

Prize he had long been denied.

Personal Struggles and Suicide

The author continued his forays into Africa and sustained several injuries

during his adventures, even surviving multiple plane crashes.

In 1954, he won the Nobel Prize in Literature. Even at this peak of his

literary career, though, the burly Hemingway's body and mind were

beginning to betray him. Recovering from various old injuries in Cuba,

Hemingway suffered from depression and was treated for numerous

conditions such as high blood pressure and liver disease.

He wrote A Moveable Feast, a memoir of his years in Paris, and retired

permanently to Idaho. There he continued to battle with deteriorating

mental and physical health.

Early on the morning of July 2, 1961, Ernest Hemingway committed

suicide in his Ketchum home.

Legacy

Hemingway left behind an impressive body of work and an iconic style

that still influences writers today. His personality and constant pursuit of

adventure loomed almost as large as his creative talent.

When asked by George Plimpton about the function of his art,

Hemingway proved once again to be a master of the "one true sentence":

"From things that have happened and from things as they exist and from

all things that you know and all those you cannot know, you make

something through your invention that is not a representation but a whole

new thing truer than anything true and alive, and you make it alive, and if

you make it well enough, you give it immortality."

poet

Ralph Waldo Emerson

1803-1882 , Boston , MA

American poet, essayist, and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson was

born on May 25, 1803, in Boston, Massachusetts. After studying at

Harvard and teaching for a brief time, Emerson entered the ministry. He

was appointed to the Old Second Church in his native city, but soon

became an unwilling preacher. Unable in conscience to administer the

sacrament of the Lord’s Supper after the death of his nineteen-year-old

wife of tuberculosis, Emerson resigned his pastorate in 1831.

The following year, he sailed for Europe, visiting Thomas Carlyle

and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Carlyle, the Scottish-born English writer,

was famous for his explosive attacks on hypocrisy and materialism, his

distrust of democracy, and his highly romantic belief in the power of the

individual. Emerson’s friendship with Carlyle was both lasting and

significant; the insights of the British thinker helped Emerson formulate

his own philosophy.

On his return to New England, Emerson became known for challenging

traditional thought. In 1835, he married his second wife, Lydia Jackson,

and settled in Concord, Massachusetts. Known in the local literary circle

as “The Sage of Concord," Emerson became the chief spokesman for

Transcendentalism, the American philosophic and literary movement.

Centered in New England during the 19th century, Transcendentalism

was a reaction against scientific rationalism.

Emerson’s first book, Nature (1836), is perhaps the best expression of his

Transcendentalism, the belief that everything in our world—even a drop

of dew—is a microcosm of the universe. His concept of the Over-Soul—a

Supreme Mind that every man and woman share—allowed

Transcendentalists to disregard external authority and to rely instead on

direct experience. “Trust thyself," Emerson’s motto, became the code of

Margaret Fuller, Bronson Alcott, Henry David Thoreau, and W. E.

Channing. From 1842 to 1844, Emerson edited the Transcendentalist

journal, The Dial.

Emerson wrote a poetic prose, ordering his essays by recurring themes

and images. His poetry, on the other hand, is often called harsh and

didactic. Among Emerson’s most well known works are Essays, First and

Second Series (1841, 1844). The First Series includes Emerson’s famous

essay, “Self-Reliance," in which the writer instructs his listener to

examine his relationship with Nature and God, and to trust his own

judgment above all others.

Emerson’s other volumes include Poems (1847),Representative Men, The

Conduct of Life (1860), and English Traits (1865). His best-known

addresses are The American Scholar (1837) and The Divinity School

Address, which he delivered before the graduates of the Harvard Divinity

School, shocking Boston’s conservative clergymen with his descriptions

of the divinity of man and the humanity of Jesus.

Emerson’s philosophy is characterized by its reliance on intuition as the

only way to comprehend reality, and his concepts owe much to the works

of Plotinus, Swedenborg, and Böhme. A believer in the “divine

sufficiency of the individual," Emerson was a steady optimist. His refusal

to grant the existence of evil caused Herman Melville, Nathaniel

Hawthorne, and Henry James, Sr., among others, to doubt his judgment.

In spite of their skepticism, Emerson’s beliefs are of central importance in

the history of American culture.

Ralph Waldo Emerson died of pneumonia on April 27, 1882.

Transcendentalism is a religious and philosophical movement that

developed during the late 1820s and '30s[1] in the Eastern region of the

United States as a protest against the general state of spirituality and, in

particular, the state of intellectualism atHarvard University and the

doctrine of the Unitarian church as taught at Harvard Divinity School.

Among the transcendentalists' core beliefs was the inherent goodness of

both people and nature. They believe that society and its institutions—

particularly organized religion and political parties—ultimately corrupt

the purity of the individual. They have faith that people are at their best

when truly "self-reliant" and independent. It is only from such real

individuals that true community could be formed.

Emerson's Nature[edit]

The publication of Ralph Waldo Emerson's 1836 essay Nature is usually

considered the moment at which transcendentalism became a major

cultural movement. Emerson wrote in his 1837 speech "The American

Scholar": "We will walk on our own feet; we will work with our own

hands; we will speak our own minds... A nation of men will for the first

time exist, because each believes himself inspired by the Divine Soul

which also inspires all men." Emerson closed the essay by calling for a

revolution in human consciousness to emerge from the brand new idealist

philosophy:

So shall we come to look at the world with new eyes. It shall answer the

endless inquiry of the intellect, — What is truth? and of the affections, —

What is good? by yielding itself passive to the educated Will. ...Build,

therefore, your own world. As fast as you conform your life to the pure

idea in your mind, that will unfold its great proportions. A correspondent

revolution in things will attend the influx of the spirit.

Individualism[edit]

Transcendentalists believed that society and its institutions—particularly

organized religion and political parties—ultimately corrupted the purity

of the individual. They had faith that people are at their best when truly

"self-reliant" and independent. It is only from such real individuals that

true community could be formed. Even with this necessary individuality,

the transcendentalists also believed that all people possessed a piece of

the "Over-soul"[9] (God). Because the Over-soul is one, this also united all

people as one being.

Indian religions[edit]

Transcendentalism has been influenced by Indian religions.[10][11][note

1]

Thoreau in Walden spoke of the Transcendentalists' debt to Indian

religions directly:

In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal

philosophy of the Bhagavat Geeta, since whose composition years of the

gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and

its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt if that philosophy is not to

be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from

our conceptions. I lay down the book and go to my well for water, and lo!

there I meet the servant of the Brahmin, priest ofBrahma,

and Vishnu and Indra, who still sits in his temple on the Ganges reading

the Vedas, or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and water-jug. I

meet his servant come to draw water for his master, and our buckets as it

were grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled

with the sacred water of the Ganges.[12]

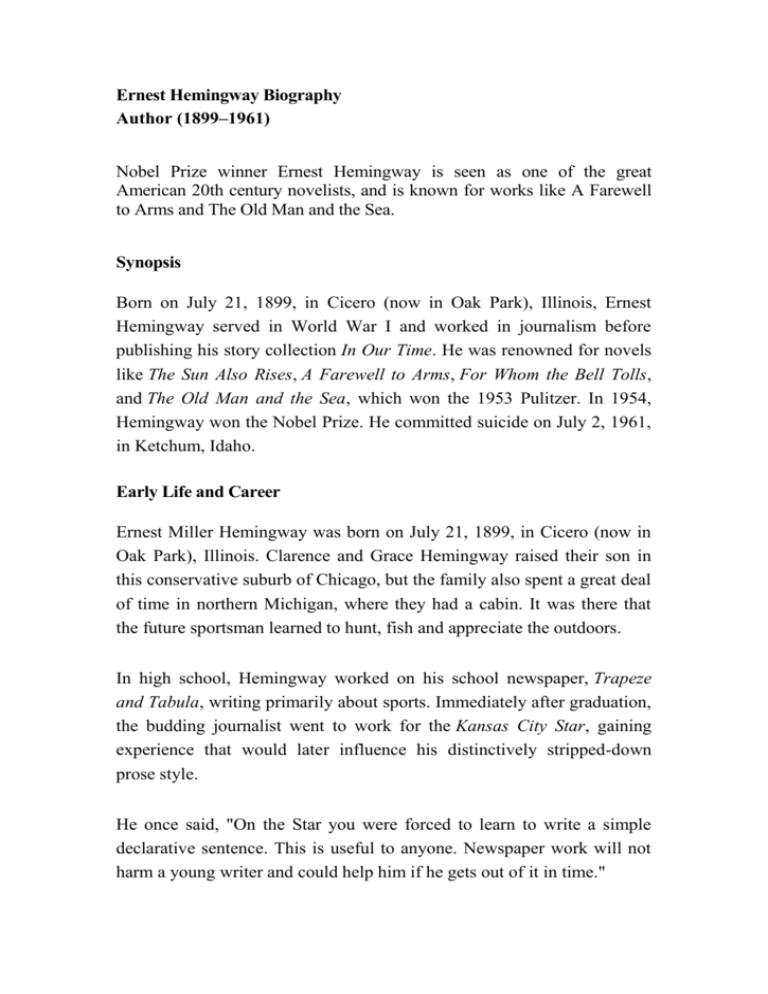

Edgar Allan Poe Biography

Writer (1809–1849)

American writer, critic and editor Edgar Allan Poe is famous for his tales

and poems of horror and mystery, including The Raven.

Synopsis

Born January 19, 1809, Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. American shortstory writer, poet, critic, and editor Edgar Allan Poe's tales of mystery

and horror initiated the modern detective story, and the atmosphere in his

tales of horror is unrivaled in American fiction. His The Raven (1845)

numbers among the best-known poems in national literature.

Early Life

With his short stories and poems, Edgar Allan Poe captured the

imagination and interest of readers around the world. His creative talents

led to the beginning of different literary genres, earning him the nickname

"Father of the Detective Story" among other distinctions. His life,

however, has become a bit of mystery itself. And the lines between fact

and fiction have been blurred substantially since his death.

The son of actors, Poe never really knew his parents. His father left the

family early on, and his mother passed away when he was only three.

Separated from his siblings, Poe went to live with John and Frances

Allan, a successful tobacco merchant and his wife, in Richmond,

Virginia. He and Frances seemed to form a bond, but he never quite

meshed with John. Preferring poetry over profits, Poe reportedly wrote

poems on the back of some of Allan's business papers.

Money was also an issue between Poe and John Allan. When Poe went to

the University of Virginia in 1826, he didn't receive enough funds from

Allan to cover all his costs. Poe turned to gambling to cover the

difference, but ended up in debt. He returned home only to face another

personal setback—his neighbor and fiancée Elmira Royster had become

engaged to someone else. Heartbroken and frustrated, Poe left the Allans.

Career Beginnings

At first, Poe seemed to be harboring twin aspirations. Poe published his

first book, Tamerlane and Other Poems in 1827, and he had joined the

army around this time. Poe wanted to go to West Point, a military

academy, and won a spot there in 1830. Before going to West Point, he

published a second collection Al Aaraaf, Tamberlane, and Minor

Poems in 1829. Poe excelled at his studies at West Point, but he was

kicked out after a year for his poor handling of his duties. Some have

speculated that he intentionally sought to be court-martialed. During his

time at West Point, Poe had fought with his foster father and Allan

decided to sever ties with him.

After leaving the academy, Poe focused his writing full time. He moved

around in search of opportunity, living in New York City, Baltimore,

Philadelphia and Richmond. From 1831 to 1835, he stayed in Baltimore

with his aunt Maria Clemm and her daughter Virginia. His young cousin,

Virginia, became a literary inspiration to Poe as well as his love interest.

The couple married in 1836 when she was only 13 (or 14 as some sources

say) years old.

Returning to Richmond in 1835, Poe went to work for a magazine called

the Southern Literary Messenger. There he developed a reputation as a

cut-throat critic, writing vicious reviews of his contemporaries. Poe also

published some of his own works in the magazine, including two parts of

his only novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym. His tenure there

proved short, however. Poe's aggressive-reviewing style and sometimes

combative personality strained his relationship with the publication, and

he left the magazine in 1837. His problems with alcohol also played a

role in his departure, according to some reports. Poe went on to brief

stints at two other papers, Burton's Gentleman's Magazine and The

Broadway Journal.

Major Works

In late 1830s, Poe published Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque, a

collection of stories. It contained several of his most spine-tingling tales,

including "The Fall of the House of Usher," "Ligeia" and "William

Wilson." Poe launched the new genre of detective fiction with 1841's

"The Murders in the Rue Morgue." A writer on the rise, he won a literary

prize in 1843 for "The Gold Bug," a suspenseful tale of secret codes and

hunting treasure.

Poe became a literary sensation in 1845 with the publication of the poem

"The Raven." It is considered a great American literary work and one of

the best of Poe's career. In the work, Poe explored some of his common

themes—death and loss. An unknown narrator laments the demise of his

great love Lenore. That same year, he found himself under attack for his

stinging criticisms of his fellow poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Poe

claimed that Longfellow, a widely popular literary figure, was a

plagiarist, and this written assault on Longfellow created a bit of backlash

for Poe.

Continuing work in different forms, Poe examined his own methodology

and writing in general in several essays, including "The Philosophy of

Composition," "The Poetic Principle" and "The Rationale of Verse." He

also produced another thrilling tale, "The Cask of Amontillado," and

poems such as "Ulalume" and "The Bells."

Mysterious Death

Poe was overcome by grief after the death of his beloved Virginia in

1847. While he continued to work, he suffered from poor health and

struggled financially. His final days remain somewhat of a mystery. He

left Richmond on September 27, 1849, and was supposedly on his way to

Philadelphia. On October 3, Poe was found in Baltimore in great distress.

He was taken to Washington College Hospital where he died on October

7. His last words were "Lord, help my poor soul."

At the time, it was said that Poe died of "congestion of the brain." But his

actual cause of death has been the subject of endless speculation. Some

experts believe that alcoholism led to his demise while others offer up

alternative theories. Rabies, epilepsy, carbon monoxide poisoning are just

some of the conditions thought to have led to the great writer's death.

Shortly after his passing, Poe's reputation was badly damaged by his

literary adversary Rufus Griswold. Griswold, who had been sharply

criticized by Poe, took his revenge in his obituary of Poe, portraying the

gifted yet troubled writer as a mentally deranged drunkard and

womanizer. He also penned the first biography of Poe, which helped

cement some of these misconceptions in the public's minds.

While he never had financial success in his lifetime, Poe has become one

of America's most enduring writers. His works are as compelling today as

there were more than a century ago. A bright, imaginative thinker, Poe

crafted stories and poems that still shock, surprise and move modern

readers.

James Baldwin Biography

Writer (1924–1987)

James Baldwin was an essayist, playwright and novelist regarded as a

highly insightful, iconic writer with works like The Fire Next Time and

Another Country.

Synopsis

Born on August 2, 1924, in New York City, James Baldwin published the

1953 novel Go Tell It on the Mountain, going on to garner acclaim for his

insights on race, spirituality and humanity. Other novels

included Giovanni's Room, Another Country and Just Above My Head as

well as essay works like Notes of a Native Son and The Fire Next Time.

Having lived in France, he died on December 1, 1987 in Saint-Paul de

Vence.

Early Life

Writer and playwright James Baldwin was born August 2, 1924, in

Harlem, New York. One of the 20th century's greatest writers, Baldwin

broke new literary ground with the exploration of racial and social issues

in his many works. He was especially well known for his essays on the

black experience in America.

Baldwin was born to a young single mother, Emma Jones, at Harlem

Hospital. She reportedly never told him the name of his biological father.

Jones married a Baptist minister named David Baldwin when James was

about three years old. Despite their strained relationship, he followed in

his stepfather's footsteps—who he always referred to as his father—

during his early teen years. He served as a youth minister in a Harlem

Pentecostal church from the ages of 14 to 16.

Baldwin developed a passion for reading at an early age, and

demonstrated a gift for writing during his school years. He attended

DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, where he worked on the

school's magazine with future famous photographer Richard Avedon. He

published numerous poems, short stories and plays in the magazine, and

his early work showed an understanding for sophisticated literary devices

in a writer of such a young age.

After graduating high school in 1942, he had to put his plans for college

on hold to help support his family, which included seven younger

children. He took whatever work he could find, including laying railroad

tracks for the U.S. Army in New Jersey. During this time, Baldwin

frequently encountered discrimination, being turned away from

restaurants, bars and other establishments because he was AfricanAmerican. After being fired from the New Jersey job, Baldwin sought

other work and struggled to make ends meet.

Aspiring Writer

On July 29, 1943, Baldwin lost his father—and gained his eighth sibling

the same day. He soon moved to Greenwich Village, a New York City

neighborhood popular with artists and writers. Devoting himself to

writing a novel, Baldwin took odd jobs to support himself. He befriended

writer Richard Wright, and through Wright he was able to land a

fellowship in 1945 to cover his expenses. Baldwin started getting essays

and short stories published in such national periodicals as The

Nation, Partisan Review and Commentary.

Three years later, Baldwin made a dramatic change in his life, and moved

to Paris on another fellowship. The shift in location freed Baldwin to

write more about his personal and racial background. "Once I found

myself on the other side of the ocean, I see where I came from very

clearly...I am the grandson of a slave, and I am a writer. I must deal with

both," Baldwin once told The New York Times. The move marked the

beginning of his life as a "transatlantic commuter," dividing his time

between France and the United States.

Early Works and Sexuality

Baldwin had his first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, published in

1953. The loosely autobiographical tale focused on the life of a young

man growing up in Harlem grappling with father issues and his religion.

"Mountain is the book I had to write if I was ever going to write anything

else. I had to deal with what hurt me most. I had to deal, above all, with

my father," he later said.

In 1954, Baldwin received a Guggenheim fellowship. He published his

next novel, Giovanni's Room, the following year. The work told the story

of an American living in Paris, and broke new ground for its complex

depiction of homosexuality, a then-taboo subject. Love between men was

explored in a later Baldwin novel Just Above My Head (1978). The

author would also use his work to explore interracial relationships,

another controversial topic for the times, as seen in the 1962

novel Another Country.

Baldwin was open about his homosexuality and relationships with both

men and women. Yet he believed that the focus on rigid categories was

just a way of limiting freedom, and that human sexuality is more fluid

and less binary than often expressed in the U.S. "If you fall in love with a

boy, you fall in love with a boy," the writer said in a 1969 interview when

asked if gayness was an aberration, asserting that such views were an

indication of narrowness and stagnation.

Writing About Race

Baldwin explored writing for the stage a well. He wrote The Amen

Corner, which looked at the phenomenon of storefront Pentecostal

religion. The play was produced at Howard University in 1955, and later

on Broadway in the mid-1960s.

It was his essays, however, that helped establish Baldwin as one of the

top writers of the times. Delving into his own life, he provided an

unflinching look at the black experience in America through such works

as Notes of a Native Son (1955) and Nobody Knows My Name: More

Notes of a Native Son(1961). Nobody Knows My Name hit the bestsellers

list, selling more than a million copies. While not a marching or sit-in

style activist, Baldwin emerged as one of the leading voices in the Civil

Rights Movement for his compelling work on race.

'The Fire Next Time'

In 1963, there was a noted change in Baldwin's work with The Fire Next

Time. This collection of essays was meant to educate white Americans on

what it meant to be black. It also offered white readers a view of

themselves through the eyes of the African-American community. In the

work, Baldwin offered a brutally realistic picture of race relations, but he

remained hopeful about possible improvements. "If we...do not falter in

our duty now, we may be able...to end the racial nightmare." His words

struck a cord with the American people, and The Fire Next Time sold

more than a million copies.

That same year, Baldwin was featured on the cover of Time magazine.

"There is not another writer—white or black—who expresses with such

poignancy and abrasiveness the dark realities of the racial ferment in

North and South,"Time said in the feature.

Baldwin wrote another play, Blues for Mister Charlie, which debuted on

Broadway in 1964. The drama was loosely based on the 1955 racially

motivated murder of a young African-American boy named Emmett Till.

This same year, his book with friend Richard Avalon, entitled Nothing

Personal, hit bookstore shelves. The work was a tribute to slain Civil

Rights leader Medgar Evers. Baldwin also published a collection of short

stories, Going to Meet the Man, around this time.

In his 1968 novel Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone, Baldwin

returned to popular themes—sexuality, family and the black experience.

Some critics panned the novel, calling it a polemic rather than a novel. He

was also criticized for using the first-person singular, the "I," for the

book's narration.

Later Works and Legacy

By the early 1970s, Baldwin seemed to despair over the racial situation.

He witnessed so much violence in the previous decade—especially the

assassinations of Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.—because

of racial hatred. This disillusionment became apparent in his work, which

employed a more strident tone than in earlier works. Many critics point

to No Name in the Street, a 1972 collection of essays, as the beginning of

the change in Baldwin's work. He also worked on a screenplay around

this time, trying to adapt The Autobiography of Malcolm X by Alex Haley

for the big screen.

While his literary fame faded somewhat in his later years, Baldwin

continued to produce new works in a variety of forms. He published a

collection of poems, Jimmy's Blues: Selected Poems, in 1983 as well as

the 1987 novelHarlem Quartet. Baldwin also remained an astute observer

of race and American culture. In 1985, he wrote The Evidence of Things

Not Seen about the Atlanta child murders. Baldwin also spent years

sharing his experiences and views as a college professor. In the years

before his death, he taught at University of Massachusetts at Amherst and

Hampshire College.

Baldwin died on December 1, 1987, at his home in St. Paul de Vence,

France. Never wanting to be a spokesperson or a leader, Baldwin saw his

personal mission as bearing "witness to the truth." He accomplished this

mission through his extensive, rapturous literary legacy.

Henry James Biography

Author (1843–1916)

Born on April 15, 1843, in New York City, Henry James became one of

his generation's most well-known writers and remains so to this day for

such works as The Portrait of a Lady and The Turn of the Screw. Having

lived in England for 40 years, James became a British subject in 1915, the

year before his death. He died on February 28, 1916, in London, England.

Henry James (1843-1916), noted American-born English essayist, critic,

and author of the realism movement wrote The Ambassadors (1903), The

Turn of the Screw (1898), and The Portrait of a Lady (1881);

"I always understood," he continued, "though it was so strange--so pitiful.

You wanted to look at life for yourself--but you were not allowed; you

were punished for your wish. You were ground in the very mill of the

conventional!"--Ch. 54

James's works, many of which were first serialised in the magazine The

Atlantic Monthly include narrative romances with highly developed

characters set amongst illuminating social commentary on politics, class,

and status, as well as explorations of the themes of personal freedom,

feminism, and morality. In his short stories and novels he employs

techniques of interior monologue and point of view to expand the readers'

enjoyment of character perception and insight. Often comparing the Old

World with the New, and influenced by Honore de Balzac, Henrik

Ibsen, Charles Dickens, and Nathaniel Hawthorne of whose work he

wrote "too original and exquisite to pass away" James would become

widely respected in North America and Europe, earning honorary degrees

from Harvard and Oxford Universities, in 1911 and 1912 respectively. He

was acquainted with many notable literary figures of the day

including Robert Browning, Ivan S. Turgenev, Emile Zola, Lord Alfred

Tennyson, and Gustave Flaubert. American-born and never married,

James would live the majority of his life in Europe, becoming a British

citizen in 1915 after the outbreak of World War I. Many of his works

have inspired other author's works and adaptations to the stage and

screen.

Henry James was born on 15 April 1843 in New York City, New York

State, United States, the second of five children born to theologian Henry James

Sr. (1811-1882) and Mary Robertson nee Walsh. Henry James Sr. was one of the

most wealthy intellectuals of the time, connected with noted philosophers and

transcendentalists as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, as well

as Nathaniel Hawthorne, Thomas Carlyle, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow;

fellow friends and influential thinkers of the time who would have a

profound effect on his son's life. Education was of the utmost importance

to Henry Sr. and the family spent many years in Europe and the major

cities of England, Italy, Switzerland, France, and Germany, his children

being tutored in languages and literature.

After several attempts at attending schools to study science and law, by

1864 James decided he would become a writer. He was always a

voracious reader and he now immersed himself in French, Russian,

English, and American classic literature. He ventured out on his own

travels to Europe, wrote book reviews, and submitted stories to

magazines such as the North American Review, Nation, North American

Tribune, Macmillan's, and The Atlantic Monthlywhich also serialised his

first novel Watch and Ward (1871). James left America and lived for a

time in Paris, France before moving to London, England in 1876. He

continued his prodigious output of short stories and novels

includingRoderick

Hudson (1875), The

American (1877), The

Europeans (1878),Confidence (1879), Washington

Square (1880), The

Pension Beaurepas (1881), and his extended critical critical

essay Hawthorne (1879). He also wrote the novella Daisy Miller (1879)

which he later based a play on; one of many that proved unsuccessful. A

Little Tour In France (1884) was followed by The Bostonians (1886), The

Aspern

Papers (1888), The

Reverberator (1888), The

Tragic

Muse (1890), The Pupil (1891), Sir Dominick Ferrand (1892), The Death

of the Lion (1894), The Coxon Fund (1894), and The Altar of the

Dead (1895).

In 1897 James retired from the hectic city of London to the quieter town

of Rye in East Sussex, where James bought "Lamb House" and continued

to writeWhat Maisie Knew (1897), In The Cage (1898), The Awkward

Age (1899), The Wings of the Dove (1902), The Beast in the

Jungle (1903), The Golden Bowl(1904), Italian Hours (1909), and The

Outcry (1911). Autobiographies include A Small Boy And

Others (1913), Notes Of A Son And Brother (1914), and The Middle

Years (1917).

In 1904 James travelled to America where he embarked on a crosscountry lecture tour, which inspired his series of essays first published

in North American Review, Harper's, The Fortnightly Review then in

1907 as The American Scene. When World War I broke out, being an

American ex-patriate, James was not happy with America's reluctance to

join the war and became a British Citizen in 1915. In 1916 he was

awarded the Order of Merit by King George V.

After several years of decline and a stroke a few months earlier, Henry

James died of pneumonia on 28 February 1916. His ashes were interred at

the Cambridge Cemetery in Massachusetts, United States, his stone

inscribed"Novelist, Citizen of Two Countries, Interpreter of His

Generation On Both Sides Of The Sea". A memorial stone was placed for

him in the Poets' Corner of Westminster Abbey, London, England in

1976.

"Live all you can; it's a mistake not to. It doesn't so much matter what you

do in particular so long as you have your life. If you haven't had that

what have you had?--from the Preface of The Ambassadors

Biography written by C. D. Merriman for Jalic Inc. Copyright Jalic Inc.

2008. All Rights Reserved.

The above biography is copyrighted. Do not republish it without

permission.

Forum Discussions on Henry James

b. Oct. 16, 1888, New York, N.Y., U.S. d. Nov. 27, 1953, Boston,

Mass. in full EUGENE GLADSTONE O'NEILL foremost American

dramatist and winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1936. His

masterpiece, Long Day's Journey into Night (produced posthumously

1956), is at the apex of a long string of great plays, including Beyond

the Horizon (1920), Anna Christie (1922), Strange Interlude (1928),

Ah! Wilderness (1933), and The Iceman Cometh (1946).

Early life

O'Neill was born into the theatre. His father, James O'Neill, was a

successful touring actor in the last quarter of the 19th century whose

most famous role was that of the Count of Monte Cristo in a stage

adaptation of the Alexandre Dumas père novel. His mother, Ella,

accompanied her husband back and forth across the country, settling

down only briefly for the birth of her first son, James, Jr., and of

Eugene.

Eugene, who was born in a hotel, spent his early childhood in hotel

rooms, on trains, and backstage. Although he later deplored the

nightmare insecurity of his early years and blamed his father for the

difficult, rough-and-tumble life the family led--a life that resulted in

his mother's drug addiction--Eugene had the theatre in his blood. He

was also, as a child, steeped in the peasant Irish Catholicism of his

father and the more genteel, mystical piety of his mother, two

influences, often in dramatic conflict, which account for the high sense

of drama and the struggle with God and religion that distinguish

O'Neill's plays.

O'Neill was educated at boarding schools--Mt. St. Vincent in the

Bronx and Betts Academy in Stamford, Conn. His summers were

spent at the family's only permanent home, a modest house

overlooking the Thames River in New London, Conn. He attended

Princeton University for one year (1906-07), after which he left school

to begin what he later regarded as his real education in "life

experience." The next six years very nearly ended his life. He shipped

to sea, lived a derelict's existence on the waterfronts of Buenos Aires,

Liverpool, and New York City, submerged himself in alcohol, and

attempted suicide. Recovering briefly at the age of 24, he held a job

for a few months as a reporter and contributor to the poetry column of

the New London Telegraph but soon came down with tuberculosis.

Confined to the Gaylord Farm Sanitarium in Wallingford, Conn., for

six months (1912-13), he confronted himself soberly and nakedly for

the first time and seized the chance for what he later called his

"rebirth." He began to write plays.

Entry into theatre

O'Neill's first efforts were awkward melodramas, but they were about

people and subjects--prostitutes, derelicts, lonely sailors, God's

injustice to man--that had, up to that time, been in the province of

serious novels and were not considered fit subjects for presentation on

the American stage. A theatre critic persuaded his father to send him

to Harvard to study with George Pierce Baker in his famous

playwriting course. Although what O'Neill produced during that year

(1914-15) owed little to Baker's academic instruction, the chance to

work steadily at writing set him firmly on his chosen path.

O'Neill's first appearance as a playwright came in the summer of 1916,

in the quiet fishing village of Provincetown, Mass., where a group of

young writers and painters had launched an experimental theatre. In

their tiny, ramshackle playhouse on a wharf, they produced his one-act

sea play Bound East for Cardiff. The talent inherent in the play was

immediately evident to the group, which that fall formed the

Playwrights' Theater in Greenwich Village. Their first bill, on Nov. 3,

1916, included Bound East for Cardiff--O'Neill's New York debut.

Although he was only one of several writers whose plays were

produced by the Playwrights' Theater, his contribution within the next

few years made the group's reputation. Between 1916 and 1920, the

group produced all of O'Neill's one-act sea plays, along with a number

of his lesser efforts. By the time his first full-length play, Beyond the

Horizon, was produced on Broadway, Feb. 2, 1920, at the Morosco

Theater, the young playwright already had a small reputation.

Beyond the Horizon impressed the critics with its tragic realism, won

for O'Neill the first of four Pulitzer prizes in drama--others were for

Anna Christie, Strange Interlude, and Long Day's Journey into Night-and brought him to the attention of a wider theatre public. For the next

20 years his reputation grew steadily, both in the United States and

abroad; after Shakespeare and Shaw, O'Neill became the most widely

translated and produced dramatist.

Period of the major works

O'Neill's capacity for and commitment to work were staggering.

Between 1920 and 1943 he completed 20 long plays--several of them

double and triple length--and a number of shorter ones. He wrote and

rewrote many of his manuscripts half a dozen times before he was

satisfied, and he filled shelves of notebooks with research notes,

outlines, play ideas, and other memoranda. His most-distinguished

short plays include the four early sea plays, Bound East for Cardiff, In

the Zone, The Long Voyage Home, and The Moon of the Caribbees,

which were written between 1913 and 1917 and produced in 1924

under the overall title S.S. Glencairn; The Emperor Jones (about the

disintegration of a Pullman porter turned tropical-island dictator); and

The Hairy Ape (about the disintegration of a displaced steamship coal

stoker).

O'Neill's plays were written from an intensely personal point of view,

deriving directly from the scarring effects of his family's tragic

relationships--his mother and father, who loved and tormented each

other; his older brother, who loved and corrupted him and died of

alcoholism in middle age; and O'Neill himself, caught and torn

between love for and rage at all three.

Among his most-celebrated long plays is Anna Christie, perhaps the

classic American example of the ancient "harlot with a heart of gold"

theme; it became an instant popular success. O'Neill's serious, almost

solemn treatment of the struggle of a poor Swedish-American girl to

live down her early, enforced life of prostitution and to find happiness

with a likable but unimaginative young sailor is his least-complicated

tragedy. He himself disliked it from the moment he finished it, for, in

his words, it had been "too easy."

The first full-length play in which O'Neill successfully evoked the

starkness and inevitability of Greek tragedy that he felt in his own life

was Desire Under the Elms. Drawing on Greek themes of incest,

infanticide, and fateful retribution, he framed his story in the context

of his own family's conflicts. This story of a lustful father, a weak son,

and an adulterous wife who murders her infant son was told with a

fine disregard for the conventions of the contemporary Broadway

theatre. Because of the sparseness of its style, its avoidance of

melodrama, and its total honesty of emotion, the play was acclaimed

immediately as a powerful tragedy and has continued to rank among

the great American plays of the 20th century.

In The Great God Brown, O'Neill dealt with a major theme that he

expressed more effectively in later plays--the conflict between

idealism and materialism. Although the play was too metaphysically

intricate to be staged successfully in 1926, it was significant for its

symbolic use of masks and for the experimentation with

expressionistic dialogue and action--devices that since have become

commonly accepted both on the stage and in motion pictures. In spite

of its confusing structure, the play is rich in symbolism and poetry, as

well as in daring technique, and it became a forerunner of avant-garde

movements in American theatre.

O'Neill's innovative writing continued with Strange Interlude. This

play was revolutionary in style and length: when first produced, it

opened in late afternoon, broke for a dinner intermission, and ended at

the conventional hour. Techniques new to the modern theatre included

spoken asides or soliloquies to express the characters' hidden thoughts.

The play is the saga of Everywoman, who ritualistically acts out her

roles as daughter, wife, mistress, mother, and platonic friend.

Although it was innovative and startling in 1928, its obvious Freudian

overtones have rapidly dated the work.

One of O'Neill's enduring masterpieces, Mourning Becomes Electra,

represents the playwright's most complete use of Greek forms, themes,

and characters. Based on the Oresteia trilogy by Aeschylus, it was

itself three plays in one. To give the story contemporary credibility,

O'Neill set the play in the New England of the Civil War period, yet

he retained the forms and the conflicts of the Greek characters: the

heroic leader returning from war; his adulterous wife, who murders

him; his jealous, repressed daughter, who avenges him through the

murder of her mother; and his weak, incestuous son, who is goaded by

his sister first to matricide and then to suicide.

Following a long succession of tragic visions, O'Neill's only comedy,

Ah, Wilderness!, appeared on Broadway in 1933. Written in a

lighthearted, nostalgic mood, the work was inspired in part by the

playwright's mischievous desire to demonstrate that he could portray

the comic as well as the tragic side of life. Significantly, the play is set

in the same place and period, a small New England town in the early

1900s, as his later tragic masterpiece, Long Day's Journey into Night.

Dealing with the growing pains of a sensitive, adolescent boy, Ah,

Wilderness! was characterized by O'Neill as "the other side of the

coin," meaning that it represented his fantasy of what his own youth

might have been, rather than what he believed it to have been (as

dramatized later in Long Day's Journey into Night).

The Iceman Cometh, the most complex and perhaps the finest of the

O'Neill tragedies, followed in 1939, although it did not appear on

Broadway until 1946. Laced with subtle religious symbolism, the play

is a study of man's need to cling to his hope for a better life, even if he

must delude himself to do so.

Even in his last writings, O'Neill's youth continued to absorb his

attention. The posthumous production of Long Day's Journey into

Night brought to light an agonizingly autobiographical play, one of

O'Neill's greatest. It is straightforward in style but shattering in its

depiction of the agonized relations between father, mother, and two

sons. Spanning one day in the life of a family, the play strips away

layer after layer from each of the four central figures, revealing the

mother as a defeated drug addict, the father as a man frustrated in his

career and failed as a husband and father, the older son as a bitter

alcoholic, and the younger son as a tubercular, disillusioned youth

with only the slenderest chance for physical and spiritual survival.

O'Neill's tragic view of life was perpetuated in his relationships with

the three women he married--two of whom he divorced--and with his

three children. His elder son, Eugene O'Neill, Jr. (by his first wife,

Kathleen Jenkins), committed suicide at 40, while his younger son,

Shane (by his second wife, Agnes Boulton), drifted into a life of

emotional instability. His daughter, Oona (also by Agnes Boulton),

was cut out of his life when, at 18, she infuriated him by marrying

Charlie Chaplin, who was O'Neill's age.

Until some years after his death in 1953, O'Neill, although respected

in the United States, was more highly regarded abroad. Sweden, in

particular, always held him in high esteem, partly because of his

publicly acknowledged debt to the influence of the Swedish

playwright August Strindberg, whose tragic themes often echo in

O'Neill's plays. In 1936 the Swedish Academy gave O'Neill the Nobel

Prize for Literature, the first time the award had been conferred on an

American playwright.

O'Neill's most ambitious project for the theatre was one that he never

completed. In the late 1930s he conceived of a cycle of 11 plays, to be

performed on 11 consecutive nights, tracing the lives of an American

family from the early 1800s to modern times. He wrote scenarios and

outlines for several of the plays and drafts of others but completed

only one in the cycle--A Touch of the Poet--before a crippling illness

ended his ability to hold a pencil. An unfinished rough draft of another

of the cycle plays, More Stately Mansions, was published in 1964 and

produced three years later on Broadway, in spite of written

instructions left by O'Neill that the incomplete manuscript be

destroyed after his death.

O'Neill's final years were spent in grim frustration. Unable to work, he

longed for his death and sat waiting for it in a Boston hotel, seeing no

one except his doctor, a nurse, and his third wife, Carlotta Monterey.

O'Neill died as broken and tragic a figure as any he had created for the

stage.

Assessment

O'Neill was the first American dramatist to regard the stage as a

literary medium and the only American playwright ever to receive the

Nobel Prize for Literature. Through his efforts, the American theatre

grew up during the 1920s, developing into a cultural medium that

could take its place with the best in American fiction, painting, and

music. Until his Beyond the Horizon was produced, in 1920,

Broadway theatrical fare, apart from musicals and an occasional

European import of quality, had consisted largely of contrived

melodrama and farce. O'Neill saw the theatre as a valid forum for the

presentation of serious ideas. Imbued with the tragic sense of life, he

aimed for a contemporary drama that had its roots in the most

powerful of ancient Greek tragedies--a drama that could rise to the

emotional heights of Shakespeare. For more than 20 years, both with

such masterpieces as Desire Under the Elms, Mourning Becomes

Electra, and The Iceman Cometh and by his inspiration to other

serious dramatists, O'Neill set the pace for the blossoming of the

Broadway theatre. (B.Ge.) (A.Ge.)

© 1999-2000 Britannica.com and Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

Copyright

John Steinbeck Biography

Author (1902–1968)

© 1999-2013 eOneill.com

John Steinbeck was an American novelist whose Pulitzer Prize-winning

novel, The Grapes of Wrath, portrayed the plight of migrant workers during

the Great Depression.

Synopsis

Born on February 27, 1902, in Salinas, California, John Steinbeck

dropped out of college and worked as a manual laborer before achieving

success as a writer. His 1939 novel, The Grapes of Wrath, about the

migration of a family from the Oklahoma Dust Bowl to California, won a

Pulitzer Prize and a National Book Award. Steinbeck served as a war

correspondent during World War II, and was awarded the Nobel Prize for

Literature in 1962. He died in New York City in 1968.

Early Years

Famed novelist John Ernst Steinbeck Jr. was born on February 27, 1902,

in Salinas, California. His books, including his landmark work The

Grapes of Wrath (1939), often dealt with social and economic issues.

Steinbeck was raised with modest means. His father, John Ernst

Steinbeck, tried his hand at several different jobs to keep his family fed:

He owned a feed-and-grain store, managed a flour plant and served as

treasurer of Monterey County. His mother, Olive Hamilton Steinbeck,

was a former schoolteacher.

For the most part, Steinbeck—who grew up with three sisters—had a

happy childhood. He was shy, but smart, and formed an early

appreciation for the land, and in particular California's Salinas Valley,

which would greatly inform his later writing. According to accounts,

Steinbeck decided to become a writer at the age of 14, often locking

himself in his bedroom to write poems and stories. In 1919, Steinbeck

enrolled at Stanford University—a decision that had more to do with

pleasing his parents than anything else—but the budding writer would

prove to have little use for college.

Over the next six years, Steinbeck drifted in and out of school, eventually

dropping out for good in 1925, without a degree.

Early Career

Following Stanford, Steinbeck tried to make a go of it as a freelance

writer. He briefly moved to New York City, where he found work as a

construction worker and a newspaper reporter, but then scurried back to

California, where he took a job as a caretaker in Lake Tahoe. It was

during this time that Steinbeck wrote his first novel, Cup of Gold (1929),

and met and married his first wife, Carol Henning. Over the following

decade, with Carol's support and paycheck, he continued to pour himself

into his writing.

Steinbeck's follow-up novels, The Pastures of Heaven (1932) and To a

God Unknown (1933), received tepid reviews. It wasn't until Tortilla

Flat (1935), a humorous novel about paisano life in the Monterey region,

was released that the writer achieved real success. Steinbeck struck a

more serious tone with In Dubious Battle (1936), Of Mice and

Men (1937) and The Long Valley (1938), a collection of short stories.

Widely considered Steinbeck's finest and most ambitious novel, The

Grapes of Wrath was published in 1939. Telling the story of a

dispossessed Oklahoma family and their struggle to carve out a new life

in California at the height of the Great Depression, the book captured the

mood and angst of the nation during this time period. At the height of its

popularity, The Grapes of Wrath sold 10,000 copies per week. The work

eventually earned Steinbeck a Pulitzer Prize in 1940.

Later Life

Following that great success, John Steinbeck served as a war

correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune during World War II.

Around this same time, he traveled to Mexico to collect marine life with

friend Edward F. Ricketts, a marine biologist. Their collaboration resulted

in the book Sea of Cortez(1941), which describes marine life in the Gulf

of California.

Steinbeck continued to write in his later years, with credits

including Cannery

Row (1945), Burning

Bright (1950), East

of

Eden (1952), The Winter of Our Discontent (1961) and Travels with

Charley: In Search of America (1962). Also in 1962, the author received

the Nobel Prize for Literature—"for his realistic and imaginative

writings, combining as they do sympathetic humour and keen social

perception"

Steinbeck died of heart disease on December 20, 1968, at his home in

New York City.

Arthur Miller Biography

Playwright (1915–2005)

Arthur Miller was an American playwright whose biting criticism of

societal problems defined his genius. His best known play is Death of a

Salesman.

IN THESE GROUPS

FAMOUS LIBRAS

FAMOUS PEOPLE BORN IN NEW YORK CITY

FAMOUS PEOPLE BORN IN UNITED STATES

FAMOUS PEOPLE BORN ON OCTOBER 17

Show All Groups

quotes

“The structure of a play is always the story of how the birds came home

to roost.”

—Arthur Miller

Synopsis

Born in Harlem, New York in 1915, Arthur Miller attended the

University of Michigan before moving back east to produce plays for the

stage. His first critical and popular success was Death of a Salesman,

which opened on Broadway in 1949. His very colorful public life was

painted in part by his rocky marriage to Marilyn Monroe, and his

unwavering refusal to cooperate with the House of Un-American

Activities Committee. He was married three times and died in 2005, at

the age of 89.

Early Life

Born in Harlem, New York on October 17, 1915, Arthur Miller was

raised in a moderately affluent household until his family lost almost

everything in the Wall Street Crash of 1929. They subsequently fired the

chauffeur and moved from the Upper East Side in Manhattan to

Gravesend, Brooklyn. After graduating high school, Miller worked a few

odd jobs to save enough money to attend the University of Michigan.

While in college, he wrote for the student paper and complete his first

play, No Villain. He also took courses with the much-loved playwright

professor Kenneth Rowe, a man who taught his students how to construct

a play in order to achieve an intended effect. Inspired by Rowe's

approach, Miller moved back east to begin his career.

Playwriting Career

Things started out a bit rocky: His 1940 play, The Man Who Had All the

Luck, garnered precisely the antithesis of its title, closing after just four

performances and a stack of woeful reviews. Six years later, however, All

My Sons achieved success on Broadway, and earned him his first Tony

Award (best author). Working in the small studio that he built in

Roxbury, Connecticut, Miller wrote the first act of Death of Salesman in

less than a day. It opened on February 10, 1949 at the Morosco Theatre,

and was adored by nearly everyone. Salesman won him the triple crown

of theatrical artistry: the Pulitzer Prize, the New York Drama Critics'

Circle Award and a Tony.

In 1956, Miller left his first wife, Mary Slattery. Shortly thereafter, he

married famed actress Marilyn Monroe. Later that year, the House of UnAmerican Activities Committee refused to renew Miller's passport, and

called him in to appear before the committee—his play, The Crucible, a

dramatization of the Salem witch trials of 1692 and an allegory of

McCarthyism, was the foremost reason for their strong-armed summons.

However, Miller refused to comply with the committee's demands to

"out" people who had been active in certain political activities.

In 1961, Monroe starred in The Misfits, a film for which Miller supplied

the screenplay. Around the same time, Monroe and Miller divorced.

Within several months, Miller married Austrian-born photographer Inge

Morath. The couple had two children, Rebecca and Daniel. Miller

insisted that their son, Daniel, who was born with down syndrome, be

completely excluded from the family's personal life. Miller's son-in-law,

actor Daniel Day-Lewis, visited his wife's brother frequently, and

eventually persuaded Miller to reunite with his adult son.

Advertisement — Continue reading below

Final Years

In his final years, Miller's work continued to grapple with the weightiest

of societal and personal matters. His last play of note was The

Price (1968), a piece about family dynamics. In 2002, Miller's third wife,

Inges, died. The famed playwright promptly became engaged to 34-yearold minimalist painter

Agnes Barley. However, before the couple could walk down the aisle, on

February 10, 2005 (the 56th anniversary of Death of a Salesman's

Broadway debut), Arthur Miller, surrounded by Barley, family and

friends, died of heart failure. He was 89 years old.

Toni Morrison Biography

Writer (1931–)

Toni Morrison is a Nobel Prize- and Pulitzer Prize-winning American

novelist. Among her best known novels are The Bluest Eye, Song of

Solomon and Beloved.

Synopsis

Born on February 18, 1931, in Lorain, Ohio, Toni Morrison is a Nobel

Prize- and Pulitzer Prize-winning American novelist, editor and

professor. Her novels are known for their epic themes, vivid dialogue and

richly detailed black characters. Among her best known novels are The

Bluest Eye, Song of Solomon and Beloved. Morrison has won nearly

every book prize possible. She has also been awarded honorary degrees.

Early Career

Born Chloe Anthony Wofford on February 18, 1931, in Lorain, Ohio,

Toni Morrison was the second oldest of four children. Her father, George

Wofford, worked primarily as a welder, but held several jobs at once to

support the family. Her mother, Ramah, was a domestic worker. Morrison

later credited her parents with instilling in her a love of reading, music,

and folklore.

Living in an integrated neighborhood, Morrison did not become fully

aware of racial divisions until she was in her teens. "When I was in first

grade, nobody thought I was inferior. I was the only black in the class and

the only child who could read," she later told a reporter from The New

York Times. Dedicated to her studies, Morrison took Latin in school, and

read many great works of European literature. She graduated from Lorain

High School with honors in 1949.

At Howard University, Morrison continued to pursue her interest in

literature. She majored in English, and chose the classics for her minor.

After graduating from Howard in 1953, Morrison continued her education

at Cornell University. She wrote her thesis on the works of Virginia

Woolf and William Faulkner, and completed her master's degree in 1955.

She then moved to Texas to teach English at Texas Southern University.

In 1957, Morrison returned to Howard University to teach English. There

she met Harold Morrison, an architect originally from Jamaica. The

couple got married in 1958 and welcomed their first child, son Harold, in

1961. After the birth of her son, Morrison joined a writers group that met

on campus. She began working on her first novel with the group, which

started out as a short story.

Morrison decided to leave Howard in 1963. After spending the summer

traveling with her family in Europe, she returned to the United States

with her son. Her husband, however, had decided to move back to

Jamaica. At the time, Morrison was pregnant with their second child. She

moved back home to live with her family in Ohio before the birth of son

Slade in 1964. The following year, she moved with her sons to Syracuse,

New York, where she worked for a textbook publisher as a senior editor.

Morrison later went to work for Random House, where she edited works

for such authors as Toni Cade Bambara and Gayl Jones.

African-American Literary Star

Morrison's first novel, The Bluest Eye, was published in 1970. It told the

story of a young African-American girl who believes her incredibly

difficult life would be better if only she had blue eyes. The book received

warm reviews, but it didn't sell well. Morrison continued to explore the

African-American experience in its many forms and time periods in her

work. Her next novel,Sula (1973), explores good and evil through the

friendship of two women who grew up together. The work was

nominated for the American Book Award.

Song of Solomon (1977) became the first work by an African-American

author to be a featured selection in the book-of-the-month club

since Native Son by Richard Wright. It follows the journey of Milkman

Dead as he searches the South for his roots. Morrison received a number

of accolades for this work.

A rising literary star, Morrison was appointed to the National Council on

the Arts in 1980. The following year, Tar Baby was published. The novel

drew some inspiration from folktales, and it received a decidedly mixed

reaction from critics. Her next work, however, proved to be one of her

greatest masterpieces. Beloved (1987) explores love and the supernatural.

The main character, a former slave, is haunted by her decision to kill her

children rather than see them become slaves. Three of her children

survived, but her infant daughter died at her hand. For this spellbinding

work, Morrison won several literary awards, including the 1988 Pulitzer

Prize for Fiction. Ten years later, in 1998, the book was turned into a

movie starring Oprah Winfrey.

Branching Out

Morrison became a professor at Princeton University in 1989, and

continued to produce great works. In recognition of her contributions to

her field, she received the 1993 Nobel Prize in Literature, making her the

first African-American woman to be selected for the award. The

following year, she published the novel Jazz, which explores marital love

and betrayal.

At Princeton, Morrison established a special workshop for writers and

performers known as the Princeton Atelier in 1994. The program was

designed to help students create original works in a variety of artistic

fields. Outside of her academic work, Morrison continued to write new

works of fiction. Her next novel, Paradise (1998), which focused on a

fictional African-American town called Ruby, earned mixed reviews.

In 1999, Morrison branched out to children's literature. She worked with

her son Slade on The Big Box, The Book of Mean People (2002) and The

Ant or the Grasshopper? (2003). She has also explored other genres,

writing the play Dreaming Emmett in the mid-1980s and the lyrics for

"Four Songs" with composer Andre Previn in 1994 and "Sweet Talk"

with composer Richard Danielpour in 1997.

Her next novel, Love (2003), divides its narrative between the past and

present. Bill Cosey, a wealthy entrepreneur and owner of the Cosey Hotel

and Resort, is the center figure in the work. The flashbacks explore his

life, while his death casts a long shadow on the present part of the story.

A critic for Publisher's Weekly praised the work, stating that "Morrison

has crafted a gorgeous, stately novel whose mysteries are gradually

unearthed."

Later Works

In 2006, Morrison announced she was retiring from her post at Princeton.

That year, The New York Times Book Review named Beloved the best

novel of the past 25 years. She continued to explore new art forms,

writing the libretto for Margaret Garner, an American opera that

explores the tragedy of slavery through the true life story of one woman's

experiences. The opera debuted at the New York City Opera in 2007.

Morrison traveled back to the early days of slavery in the United States

for her next novel, A Mercy. Once again, a woman who is both a slave

and a mother must make a terrible choice regarding her child. As a critic

from theWashington Post described it, the novel is "a fusion of mystery,

history and longing." In addition to her many novels, Morrison has

written several works of non-fiction. She published collection of her nonfiction writings entitledWhat Moves at the Margin in 2008.

A champion for the arts, Morrison spoke out about censorship in October

2009 after one of her books was banned at a Michigan high school. She

served as editor for Burn This Book, a collection of essays on censorship

and the power of the written word, which was published that same year.

She told a crowd gathered for the launch of the Free Speech Leadership

Council about the importance of fighting censorship. "The thought that

leads me to contemplate with dread the erasure of other voices, of

unwritten novels, poems whispered or swallowed for fear of being

overheard by the wrong people, outlawed languages flourishing

underground, essayists' questions challenging authority never being

posed, unstaged plays, canceled films—that thought is a nightmare. As

though a whole universe is being described in invisible ink," Morrison

said.

Recent Projects

Now in her 80s, Morrison continues to be one of literature's great

storytellers. She published her latest novel, Home, in 2012. She once

again explores a period of American history—this time the post-Korean

War era. In choosing this setting, "I was trying to take the scab off the

'50s, the general idea of it as very comfortable, happy, nostalgic. Mad

Men. Oh, please. There was a horrible war you didn't call a war, where

58,000 people died. There was McCarthy," Morrison explain to

the Guardian newspaper. Her main character, Frank, is a veteran who

suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder.

While writing the novel, Morrison experienced a great personal loss. Her

son Slade, an artist, died in December 2010. The pair had collaborated

together on a number of children's books, including Big Box (1999)

and Little Cloud and Lady Wind (2010).

In addition to Home, Morrison also debuted another work in 2012: She

worked with opera director Peter Sellars and songwriter Rokia Traoré on

a new production inspired by William Shakespeare's Othello. The trio

focused on the relationship between Othello's wife Desdemona and her

African nurse, Barbary, in Desdemona, which premiered in London in the

summer of 2012.

John Updike Biography

Author (1932–2009)

Writer John Updike's works are known for their subtle depiction of

American middle-class life. His popular Rabbit series earned him two

Pulitzer

prizes.

IN THESE GROUPS

Synopsis

John Updike was born on March 18, 1932, in Reading, Pennsylvania. His

famous Rabbit series—including Rabbit,

Run (1960); Rabbit

Redux (1971);Rabbit Is Rich (1981, Pulitzer Prize); Rabbit at Rest (1990,

Pulitzer Prize); and Rabbit Remembered (2001)—follows a very ordinary

American man through the decades of the late 20th century. The most

recent installment of the series, Rabbit Remembered, centers on

characters from the earlier books in the wake of Rabbit's death. Updike

died on January 27, 2009, in Danvers, Massachusetts.

John Updike was born in Reading, Pennsylvania, and spent his first years

in nearby Shillington, a small town where his father was a high school

science teacher. The area surrounding Reading has provided the setting

for many of his stories, with the invented towns of Brewer and Olinger

standing in for Reading and Shillington. An only child, Updike and his

parents shared a house with his grandparents for much of his childhood.

When he was 13, the family moved to his mother's birthplace, a stone

farmhouse on an 80-acre farm near Plowville, eleven miles from

Shillington, where he continued to attend school.

At home, he consumed popular fiction, especially humor and mysteries.

His mother, herself an aspiring writer, encouraged him to write and draw.

He excelled in school and served as President and co-valedictorian of his

graduating class at Shillington High School. For the first three summers

after high school, he worked as a copy boy at the Reading

Eaglenewspaper, eventually producing a number of feature stories for the

paper. He received a tuition scholarship to Harvard University, where he

majored in English. As an undergraduate, he wrote stories and drew

cartoons for the Harvard Lampoon humor magazine, serving as the

magazine's president in his senior year. Before graduating, he married

fellow student Mary E. Pennington. He graduated summa cum laude from

Harvard in 1954, and in that same year sold a poem and a short story

to The New Yorker magazine.

Updike and his wife spent the following year in England, where Updike

studied at Oxford's Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art. While they

were in England, their first daughter was born and Updike met the

American writers E. B. and Katharine White, editors at The New Yorker,

who urged him to seek a job at the magazine. On returning from England,

the Updikes settled in Manhattan, where John took a position as a staff

writer at The New Yorker. He worked at the magazine for nearly two

years, writing editorials, features and reviews, but after the birth of a son

in 1957, he decided to move his growing family to the small town of

Ipswich, Massachusetts. He continued to contribute to The New

Yorker but resolved to support his family by writing full-time, without

taking a salaried position. He maintained a lifelong relationship with The

New Yorker, where many of his poems, reviews and short stories

appeared, but he resided in Massachusetts for the rest of his life.

Updike's first book of poetry, The Carpentered

Hen and Other Tame Creatures, was published

by Harper and Brothers in 1958. When the

publisher sought changes to the ending of his

first novel, The Poorhouse Fair, he moved to

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. The first novel was wellreceived, and with support from the

Guggenheim Fellowship, Updike undertook a

more ambitious novel, Rabbit, Run. The novel

introduced one of Updike's most memorable

characters, the small-town athlete, Harry

"Rabbit" Angstrom. Knopf feared that his frank

description of Rabbit's sexual adventures could

lead to prosecution for obscenity, and made a

number of changes to the text. The book was published to widespread

acclaim without legal repercussions. The original text was restored for the

British edition a few years later, and subsequent American editions of the

book have reflected the author's original intent. Updike's reputation as a

leading author of his generation was established.

After the birth of a third child, Updike rented a one-room office above a

restaurant in Ipswich, where he wrote for several hours every morning,

six days a week, a schedule he adhered to throughout his career. In 1963,

he received the National Book Award for his novel The Centaur, inspired

by his childhood in Pennsylvania. The following year, at age 32, he

became the youngest person ever elected to the National Institute of Arts

and Letters, and was invited by the State Department to tour eastern

Europe as part of a cultural exchange program between the United States

and the Soviet Union. In 1967, he joined the author Robert Penn Warren

and other American writers in signing a letter urging Soviet writers to

defend Jewish cultural institutions under attack by the Soviet government.

In 1968, Updike's novel Couples created a

national sensation with its portrayal of the

complicated relationships among a set of

young married couples in the suburbs. It

remained on the best-seller lists for over a

year and prompted a Time magazine cover

story featuring Updike. InBech: A

Book (1970), Updike introduced a new

protagonist, the imaginary novelist Henry

Bech, who, like Rabbit Angstrom, was

destined to reappear in Updike's fiction for

many years. Rabbit Angstrom reappeared

in Rabbit Redux(1971).

In the 1970s, Updike continued to travel as

a cultural ambassador of the United States, and in 1974 he joined authors

John Cheever, Arthur Miller and Richard Wilbur in calling on the Soviet

government to cease its persecution of dissident author Alexander

Solzhenitsyn. Updike separated from his wife Mary in 1974 and moved to

Boston where he taught briefly at Boston University. Two years later, the

Updikes were divorced, and in 1977 he married Martha Ruggles

Bernhard, settling with her and her three children in Georgetown,

Massachusetts.

Rabbit is Rich, published in 1981,

received numerous awards, including

the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. In 1983

Updike's other alter ego, Harry Bech,

reappeared in Bech is Back, and

Updike

was

featured

in

a

second Time magazine cover story,

"Going Great at 50." Among his

novels of the 1980s and 1990s are a

trilogy retelling The Scarlet Letter from the points of view of three

different characters, and a prequel to Hamlet, entitled Gertrude and

Claudius. In 1991 he received a second Pulitzer Prize for Rabbit at Rest.

He was only the third American to win a second Pulitzer Prize in the

fiction category.

In an autobiographical essay, Updike famously identified sex, art, and

religion as "the three great secret things" in human experience. The