View paper

advertisement

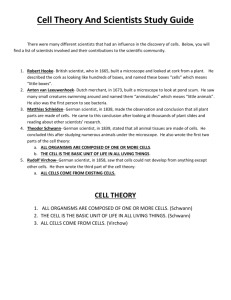

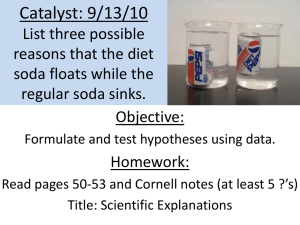

How they look like and what they do? The perception of Chilean students’ on scientists and scientific work. Abstract This paper describes the scientific view of 363 secondary female Chilean students according to the Draw a Scientist Test (Chambers, 1983). The sample includes participants from 9 schools both private and public school, including a wide range of socioeconomic level (SEL). The drawings were analysed using Chambers (1983) 7 indicators of stereotype image, alternatives indicators and no stereotype indicators. The data were coded and then analysed using not parametric statistical test. The results shown that the students usually present a stereotypical image of the scientist, nonetheless it was also found cases in which the scientist were described with darker hair, casual clothing and smile faces. The answer to the question: “What is the scientist doing?” showed generally basic scientific actions as observing and comparing. However it was also found in a lower frequency hypothesis formulation and interpretation. The comparative analysis using SEL indicates difference in both drawing and narratives. Implications for the scientific education in different SEL schools are discussed. Objectives or purposes The work of scientist has been identified as a critical for the development of all countries. This idea has underpinned an increscent worldwide investment in the preparation of scientist in all level including primary and secondary schools. However studies suggest difficulties and challenges in order to implement and improve the teaching of science at school level. One of these issues regards with the perception of students about the role of scientist and preconception about science itself. The purpose of this study was to examine Chilean female students’ perceptions of scientists through their images drawn on the DAST. The following research questions established the direction of the research: (1) What are the perceptions of scientists that are held by Chilean female high school students? (2) What are the perceptions of scientist work are held by them? And (3) Do these perceptions differ among socioeconomic level of the schools? Perspective(s) or theoretical framework The image that students have of scientist may be related to the image that students have regarding science (Türkmen, 2008). Thus, a more realistic and less stereotypical scientist, have been associated with a more positive attitude toward science, and therefore, to the possibility of better learning, and eventually, to pursue scientific careers (Finson, Beaver, & Cramond, 1995; Finson, 2002, Türkmen, 2008). On the other hand, a negative stereotypic view of scientists is associated with a negative perception of science. The test "Draw a Scientist", developed by Chambers (1983) has been widely used for study the image that students have about scientists. This author described seven indicators of what he called a 'stereotypical scientist "(see Table 1). Other researchers have suggested additional indicators to the stereotypical image of scientists proposed by Chambers (1983). These include: male gender (Barman, 1999; Finson et al., 1995; Türkmen, 2008), work in the lab (Barman, 1999; Finson et al., 1995; Türkmen, 2008), the presence of natural elements (She,1995; Fung, 2002) and others (see also Table 1).Since less stereotyped images of a scientist have been associated with a more positive attitude towards science (Finson et al., 1995; Türkmen, 2008), it becomes interesting to study the image of scientists in the context of South America, because students at this region generally had showed poor achievements in international as PISA (OCDE, 2010). Moreover, because Chile shows a marked stratification of social classes, it becomes very interesting to see if the image of scientists is different depending on student socioeconomic status (Chambers, 1983). In Chile, international and national test about scientific competencies has shown a wide gap between students achievement of different socioeconomic levels. The gap indicates that students with low scores came from poorest contexts. Therefore, it becomes especially important to assess whether the observed differences in science learning of students, is also shown in the image that they have of scientists and science. Besides, Chile in opposition to most countries which participated in PISA, it has systematically showed a significant difference according to gender, presenting higher score on males over females’ students (2000 to 2009). Additionally, Chile present a shortage of scientists according to it needs of developments (Allende et al, 2005). Therefore, it becomes more relevant to identify the Chilean female student’s perception about scientist and scientific work. Methods, techniques or modes of inquiry Participants This research involved 363female students of grades11th (n=173) and12th (n =190). The students belonged to nine schools in the region of Valparaíso, Chile. The ages of the students ranged between 15 – 18 years. Socioeconomic status of students varied according to their school. Data Collection The DAST (Chambers, 1983) was administered by the researchers in the students’ science classes over a period of one month during the 2009 spring semester. Students were directed to complete the DAST according to the following prompt ‘Draw a scientist at work in the space below’ (Chambers, 1983; Finson, 2002; Laubach et al., 2012). On the following page of their instructions, students were directed to ‘Explain what the scientist is doing’ (as modified from Türkmen, 2008). Data Analysis For drawing analysis, 15% of the sample was analyzed for exploratory purposes, allowing the generation of new categories. The inter-rater reliability was determined to be 0.85– 0.90. Scoring was accomplished by coding each of the 15 indicators with either 1 or 0 points pending on the presence or absence of the specific indicator. The total score (0–15) for each drawing was determined by adding the traditional and alternative stereotypical subtotals. The more the items checked on the DAST-C, the more stereotypes appear in the student drawings. For the inquiry skills analysis described in the second question by the students, we follow the classification of Padilla (1990), who recognized between basic and integrated inquiry skills. This analysis was also performed by two researchers and the inter-rater reliability was > 0.90.The total score of basic and integrated skills for each response was also determined. Results and/or conclusions/points of view In general, Chilean female students viewed scientists having some stereotypical aspect such as: being a male (73%-85%), using a lab coat (60%–80%), working inside the lab (67%– 84%), and with research symbols (88%–80%). However, they also include some nontraditional stereotypical aspect such as a scientist with black or brown hair (65%-90%) and working with a smile (45%–60%). On the other hand, when we analyze the number of traditional stereotypical aspects, and the alternative stereotypical images by students (Finson, 2002; Laubach et al., 2012) the mean value were close to 3 (2.9 – 3.6 and 2.5 – 3.1respectively). The mean number of non-stereotypical aspects by student was near 2 The result of inquiry skills analysis were that most students describe scientist work doing basic science process skills such as observing (21–45%), comparing (7% – 21 %) and communicating (3–19%). Finally, when the results are analyzed by socioeconomic level, no differences were found in drawing scientist or answer the question about what was doing the scientist (Table 1 and 2). Educational importance of this study for theory, practice, and/or policy The improving of scientific preparation is a critical asset for the development of any country. Especially critical is the Chilean case were the evidence suggest a shortage of qualify scientist. Intervention at the most early stage possible could generate a high impact not only in improving the teaching but also in student´s interest. Considering the large sample collected, the results of this study can support the design of local and national initiatives for improving scientific preparation in all levels of the school. Connection to the themes of the congress This presentation is aligned with the sub-theme 3: “Exploring and Understanding Contemporary Approaches to Teaching and Learning” and specifically with the topic: “Curriculum models in different models of learning”. Considering the interest of ICSEI for international issues in education (such as science and science teaching) we believe that this study can collaborate in identifying global challenger for school and teaching improvement. References Allende, J., Asenjo, J., Babul, J., Brieva, F., Cárdenas-Jirón, G., Hervé, F., Inestrosa, N., Martínez, S., Santelices, B. y Valenzuela, P. (2005). Conclusiones y recomendaciones de informe “Avances y Proyecciones de la Ciencia Chilena-2005, Academia Chilena de Ciencias. Barman, C. (1999). Students’ views about scientists and school science: Engaging K8 teachers in a national study. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 10(1), 43-54 Chambers, D. (1983). Stereotypic images of the scientist: The Draw-A-Scientist Test. Science Education, 67(2), 255-265. Finson, K. D. (2002). Drawing a Scientist: What we do and do not know after fifty years of drawings.School Science and Mathematics, 107(7), 335–345. Finson, K., Beaver, J., y Cramond, B. (1995). Development and field test of a checklist for the Draw-A-Scientist Test. School Science and Mathematics, 95(4), 195205. Fung, Y. (2002). A comparative study of primary and secondary school students’ images of scientists.Research in Science y Technological Education, 20 (2), 199-213. Laubach, T. A., G. D. Crofford & E. A. Marek (2012) Native American Students’ Perceptions of Scientists, International Journal of Science Education, 34:11, 17691794. Matkins, J. J. (1996).Customizing the Draw-a-Scientist Test to analyze the effect that tearchers have on their student´s perceptions and attitudes toward science.AETS. Available in: http://www.ed.psu.edu/CI/Journals/96pap44.htm National Research Council (2002).Inquiry and the National Science Education Standards: A Guide for Teaching and Learning. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press OECD (2010). PISA 2009 Results: Executive Summary Padilla, M. J. (1990). Science process skills.National Association of Research in Science Teaching Publication: Research Matters - to the Science Teacher (9004). She, H. (1995). Elementary and middle school students’ image of science and scientists related to current science textbooks in Taiwan. Journal of Science Education and Technology,4, 283 – 294. Thomas, J. y Hairston, R.(2003). Adolescent students’ images of an environmental scientist: an opportunity for constructivist teaching. Electronic Journal of Science Education, 7(4), 1- 25. Türkmen, H. (2008). Turkish primary students’ perceptions about scientist and what factors affecting the image of the scientists. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science y Technology Education, 4(1), 55-61.