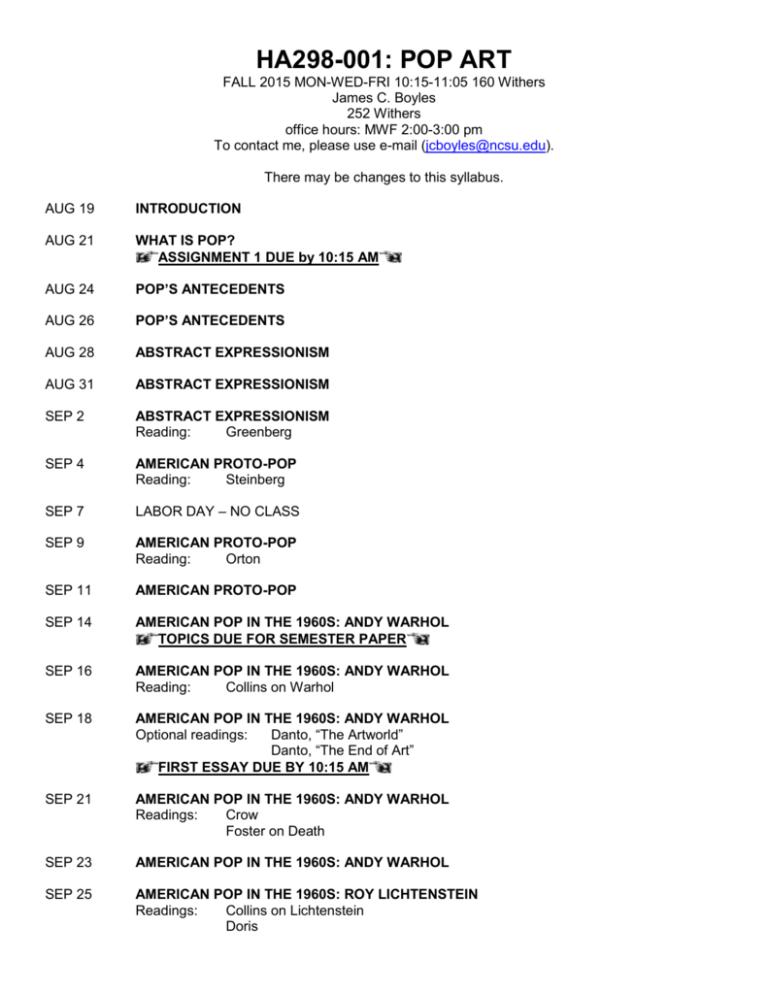

HA298-001: POP ART

FALL 2015 MON-WED-FRI 10:15-11:05 160 Withers

James C. Boyles

252 Withers

office hours: MWF 2:00-3:00 pm

To contact me, please use e-mail (jcboyles@ncsu.edu).

There may be changes to this syllabus.

AUG 19

INTRODUCTION

AUG 21

WHAT IS POP?

ASSIGNMENT 1 DUE by 10:15 AM

AUG 24

POP’S ANTECEDENTS

AUG 26

POP’S ANTECEDENTS

AUG 28

ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM

AUG 31

ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM

SEP 2

ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM

Reading:

Greenberg

SEP 4

AMERICAN PROTO-POP

Reading:

Steinberg

SEP 7

LABOR DAY – NO CLASS

SEP 9

AMERICAN PROTO-POP

Reading:

Orton

SEP 11

AMERICAN PROTO-POP

SEP 14

AMERICAN POP IN THE 1960S: ANDY WARHOL

TOPICS DUE FOR SEMESTER PAPER

SEP 16

AMERICAN POP IN THE 1960S: ANDY WARHOL

Reading:

Collins on Warhol

SEP 18

AMERICAN POP IN THE 1960S: ANDY WARHOL

Optional readings:

Danto, “The Artworld”

Danto, “The End of Art”

FIRST ESSAY DUE BY 10:15 AM

SEP 21

AMERICAN POP IN THE 1960S: ANDY WARHOL

Readings:

Crow

Foster on Death

SEP 23

AMERICAN POP IN THE 1960S: ANDY WARHOL

SEP 25

AMERICAN POP IN THE 1960S: ROY LICHTENSTEIN

Readings:

Collins on Lichtenstein

Doris

2

SEP 28

AMERICAN POP IN THE 1960S: ROY LICHTENSTEIN

SEP 30

AMERICAN POP IN THE 1960S

Reading:

Lobel

OCT 2

AMERICAN POP IN THE 1960S

PAPER BIBLIOGRAPHIES DUE BY 10:15 AM

OCT 5

AMERICAN POP IN THE 1960S

OCT 7

AMERICAN POP IN THE 1960S: PHOTOGRAPHY AND TEXT

Readings:

Schwabsky

Foster on Ruscha

OCT 9

FALL BREAK – NO CLASS

OCT 12

AMERICAN POP IN THE 1960S: PHOTOGRAPHY AND TEXT

OCT 14

AMERICAN POP IN THE 1960S: SEXUALITY AND GENDER

Reading:

Meyer

OCT 16

AMERICAN POP IN THE 1960S: SEXUALITY AND GENDER

OCT 19

AMERICAN POP AFTER THE 1960S

SECOND ESSAY DUE AT 10:15 AM

OCT 21

AMERICAN POP AFTER THE 1960S

OCT 23

NO CLASS

OCT 26

AMERICAN POP AFTER THE 1960S

OCT 28

AMERICAN POP AFTER THE 1960S

OCT 30

AMERICAN POP AFTER THE 1960S

Reading:

Bonami

NOV 2

POP OUTSIDE OF AMERICA: GREAT BRITAIN

Reading:

Cooke

NOV 4

POP OUTSIDE OF AMERICA: GREAT BRITAIN

NOV 6

POP OUTSIDE OF AMERICA: NOUVEAU REALISME

Reading:

Handa-Gagnard

NOV 9

POP OUTSIDE OF AMERICA: NOUVEAU REALISME

NOV 11

POP OUTSIDE OF AMERICA: NOUVEAU REALISME

NOV 13

POP OUTSIDE OF AMERICA: GERMANY

Readings:

Huyssen

Silverman

3

NOV 16

POP OUTSIDE OF AMERICA: GERMANY

Reading:

Ziegler and Hemken

NOV 18

POP OUTSIDE OF AMERICA: GERMANY

SEMESTER PAPER DUE BY 10:15 AM

NOV 20

POP OUTSIDE OF AMERICA: JAPAN

NOV 23

POP OUTSIDE OF AMERICA: JAPAN

NOV 25-27

THANKSGIVING – NO CLASS

NOV 30

POP OUTSIDE OF AMERICA: RUSSIA AND CHINA

Reading:

Erofeev

DEC 2

POP OUTSIDE OF AMERICA: RUSSIA AND CHINA

Reading:

Chang

DEC 4

POP OUTSIDE OF AMERICA: RUSSIA AND CHINA

DEC 14

THIRD ESSAY DUE BY 11:00 AM

MOODLE

I have set up a Moodle site (wolfware.ncsu.edu) for this course with the syllabus, course readings and

guidesheets with the important course images. Titles, creators and dates are also listed with each image. You

should either bring your laptop to class or print the guidesheets (before class) so that you can write your notes

next to the images. If you bring your laptop, you are expected to use it ONLY for class-related activities. If it is

apparent that your use of any electronic device is distracting others in the class, you will be asked to turn it off

and not use it in class for the remainder of the semester. Your final grade will be reduced with each infraction.

ASSIGNMENTS and PAPERS

ASSIGNMENT: You have a one-page assignment, which is due at 10:15 on Aug. 21. Type a brief definition of

Pop Art. You can make it up or look it up. Also include 5 terms that help to define Pop Art. The terms can be

general or specific, but they cannot be proper names (such as Andy Warhol or Coca-Cola). This assignment

will be included in your participation score. If you turn it in and do exceptional work, your participation score

will be raised. If you do not turn it in, your participation score will be lowered. No late papers will be accepted.

PAPERS: For your major grades in this course you will write three papers. Most of you can choose to do

either Option One or Option Two. However, students taking this course for honors credit must do

OPTION TWO:

Option One: You will write three formal essays on themes covered in this course. Each essay will only cover

a section of the course (1st essay due by 10:15 on Sep. 18; 2nd essay due by 10:15 on Oct. 9; 3rd essay due by

11:00 on Dec. 14). I will give two or more questions from which you will choose one and write a formal essay

of 4-5 typed pages. You may use your notes, the assigned readings, additional research and me; you may not

consult with anyone else. You will have a week to write your essays. The rubric for grading your essays is on

p. 5 of this syllabus. The first essay is worth 30% and the other two are 35%.

4

Option Two You will write two of the essays from OPTION ONE; you choose which two and they are due on

the dates listed on the syllabus. In addition to these two essays, you will write a 6-8 page formal research

paper on a topic of your choice that is related to the material of this course. By September 14, you will meet

with the professor to discuss your topic. On September 14, you will submit a written proposal. On October 2,

you will submit an annotated bibliography of your sources. The final paper is due by 10:15 AM on November

18. Each essay is worth 30% and the semester paper is 40% of your final grade.

Concerned about your writing skills? I’ll help.

Also try the University Tutorial Center (tutorial.ncsu.ed).

If you feel that you have a compelling reason that requires an extension on an essay, e-mail me at least

twenty-four hours before the essay is due for me to consider your request and give you my decision.

Otherwise, 25 POINTS WILL BE DEDUCTED from the grade of any assignment that does not have an

approved extension and is turned in after the deadline.

In order to pass this course, you must turn in all three essays by noon on Dec 15. Email any

papers submitted after 11:00 AM on Dec. 14. An incomplete will only be given upon prior

arrangement with the professor.

OTHER GRADES

PARTICIPATION: I do not give extra credit assignments. However, one way to boost your grade is classroom

participation. Positive participation (such as consistent involvement in class discussions of the material) can

change your final course score, often enough to raise your final letter grade. On the other hand, negative

participation (such as coming late, leaving early, non-course-related chatter, ringing cell phones) can change

your final score, often enough to lower your final letter grade.

ATTENDANCE: Another factor that can affect your final grade is attendance. Attendance is required and, out

of courtesy to the other members of the class, please arrive on time. Once the doors to the classroom are

closed, you may not enter (unless you have made previous arrangements with me or you are returning from

the bathroom). Two unexcused tardies or early departures will equal one absence. No more than two

unexcused absences are acceptable. Three absences will drop your final grade five points; four absences will

drop your final grade ten points. If you have five absences, you will fail the course. Only the instructor can

excuse an absence. To receive an excuse for a medically-related absence, you must bring a written

explanation from a doctor or nurse. If you must leave class early, notify me before class begins. For additional

information on the University’s attendance policy, see:

http://policies.ncsu.edu/regulation/reg-02-20-03

COURTESY: Finally, the primary function of courtesy is to help us all get through difficult situations. Learning

is difficult and to do it well, we have to concentrate. So please be aware that your behavior in class can impact

others who are trying to understand what is being discussed. I ask that you treat everyone in the class – and

that includes your professor – with courtesy.

5

GRADES

OPTION ONE: The first essay is worth 30% and the other two are 35%.

OPTION TWO: Each essay is worth 30% and the semester paper is 40% of your final grade.

A+ =

A =

A- =

B+ =

B =

100-98 (4.333)

97-94 (4)

93-90 (3.667)

89-88 (3.333)

87-84 (3)

B- =

C+ =

C =

C- =

D+ =

83-80

79-78

77-74

73-70

69-68

(2.667)

(2.333)

(2)

(1.667)

(1.333)

D = 67-64 (1)

D- = 63-60 (.667)

F = 59-0 (0)

PLAGIARISM

All sections of the University’s Code of Student Conduct apply to this course. A complete explanation can be

found at:

http://policies.ncsu.edu/policy/pol-11-35-01

With each essay, you will be required to sign the University’s Honor Pledge (“I have neither given nor received

unauthorized aid on the test or assignment.”). Plagiarism is the unauthorized use of someone else’s ideas and

the representation of those ideas as your own. There is no excuse for it and all instances of plagiarism will

result in an F for the course and other sanctions authorized by the University. To avoid the dire consequences

of being accused of plagiarism, follow all of the instructions and consult with me if you have concerns. For the

essays, you may use your notes, the Moodle materials, me and, of course, your own brilliance. Except for me,

you cannot use anyone else to help you prepare your exam essays. You can also do additional research, but

you must include citations and a bibliography that specify your borrowings from other scholars. These markers

not only indicate that you have not cheated, but they are also signs of your participation in the scholarly

conversation on art history. In other words, they make you look better. So why even bother to plagiarize?

For more information, see the History Department’s website on the honor code:

http://history.ncsu.edu/ug_resources/plagiarism_honor_code

DISABILITY SERVICES FOR STUDENTS

Reasonable accommodations will be made for students with verifiable disabilities. The primary way that the

student formally discloses to the instructor is by requesting a DSO Letter of Accommodation. This letter informs

the instructor that the student has a documented disability, states which accommodations the student is eligible

to receive, and provides information about how to arrange the accommodations. No matter how

comprehensive and well-written the letters of accommodation are, there is no substitute for student input.

Therefore, once the letter is sent, the student must communicate with each instructor to discuss the letter and

to set up accommodations. Whenever possible, it is recommended that the student contact instructors before

the semester begins or at the start of the semester. This will allow instructors to have the necessary

information in time to arrange accommodations.

Additional information can be found at:

http://policies.ncsu.edu/regulations/reg.02.20.01

6

EMERGENCIES

For health, safety, fire, and medical emergencies, dial 911 (land line) or 919-515-3000 (cell phone). This will

connect you to an emergency operator who can send help to you. Be prepared to give the operator your name,

your location, and the nature of the emergency. Don’t hang up – remain on the line until help arrives in the form

of a police officer, fire truck, or ambulance (“EMT”) and they say you can hang up. If you are the victim of a

crime, are being followed by suspicious person, see a crime in progress, witness an accident, believe someone

needs an ambulance or emergency first aid, discover a very unsafe situation, etc., you should call. The

authorities and safety officers would rather respond to several cases of non-life threatening cases than to not

be called when they could have saved someone’s life. For more information about a campus-wide emergency,

check:

www. ncsu.edu/emergency-information

OBJECTIVES, OUTCOMES AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION

I. Course Objectives

This course will help students to:

1. understand the development and impact of Pop Art.

2. translate the visual stimulation of art into words.

3. learn to interrogate works of art to recover how they reflect their original times and the changing

attitudes since then.

4. move from learning facts to making critically reasoned judgments grounded in the academic content of

the course.

5. develop art historical research skills and the standard means for expressing those skills.

II. Student Outcomes

By the end of the semester, students will demonstrate the ability to:

1. identify:

a. the basic chronological development of Pop Art;

b. major artists and works of art associated with Pop Art;

c. important theories regarding the role of Pop Art in modern society.

2. translate the visual expressions of art works into verbal formats through class discussions and papers.

3. describe both the physical appearance and the contextual framework of art works in relation to their

roles as evidence of the history of ideas in relation to Pop Art.

4. evaluate their understandings of art works (as described in outcomes 1-3) as well as the responses of

other viewers in order to develop a coherent and well-reasoned synthesis of established data and new

assessments.

5. conduct art historical research and write a formal art historical paper.

III. Assessing Student Development

Students will demonstrate their mastery of the course’s outcomes through a variety of tasks, including class

participation during general discussions of the art and themes of this period and, more specifically, through

discussions of the assigned readings, and three essays or two essays and a research paper on themes

covered in the course material.

IV. Satisfaction of Degree Requirements

This course fulfills the Arts and Letters requirement for Humanities and Social Sciences majors or a History

and Analysis requirement for Art Studies majors with a concentration in the Visual Arts.

V. Topics Courses

This course is a topics course, as designated by the course number HA298. You can repeat topics courses

and get credit, as long as the topics are different.

7

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF READINGS

1. Bonami, Francesco. “Koons ‘R’ Us,” in Jeff Koons. Edited by Francesco Bonami. Chicago: Musuem of

Contemporary Art, 208. Pp. 8-15.

2. Chang Tsong-Zung. “Pop Notes from Greater China,” in Post Pop: East Meets West. Edited by Marco

Livingstone. London: CentreInvest UK Limited, 2014. Pp. 35-46.

3. Collins, Bradford R. “Dick Tracy and the Case of Warhol’s Closet: A Psychoanalytic Detective Story,”

American Art. 15:3 (Autumn 2001): 54-79.

4. Collins, Bradford R. “Modern Romance: Lichtenstein’s Comic Book Paintings,” American Art. 17:2

(Summer 2003): 60-85.

5. Cooke, Lynne. “The Independent Group: British and American Pop Art, a ‘Palimpcestuous’ Legacy,” in

Modern Art and Popular Culture: Readings in High & Low. Edited by Kirk Varnedoe and Adam Gopnik.

New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1990. Pp. 192-216+.

6. Crow, Thomas. “Saturday Disasters: Trace and Reference in Early Warhol,” in Modern Art in the

Common Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996. Pp. 49-65 and 250-251.

7. Danto, Arthur C. “The Artworld,” Journal of Philosophy. 61:19 (1964): 571-584.

8. Danto, Arthur C. “The End of Art: A Philosophical Defense,” History and Theory. 37:4 (December

1998): 127-143.

9. Doris, Sara. “Missing Modernism,” in Roy Lichtenstein: A Retrospective. Edited by James Rondeau and

Sheena Wagstaff. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2012. Pp. 46-51.

10. Erofeev, Andrei. “The Birth of Soviet Post Pop Art,” in Post Pop: East Meets West. Edited by Marco

Livingstone. London: CentreInvest UK Limited, 2014. Pp.14-33.

11. Foster, Hal. “Death in America,” October. 75 (Winter 1996): 36-59.

12. Foster, Hal. “Ed Ruscha, or the Deadpan Image,” in The First Pop Age. Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press, 2012. Pp. 210-247 and 307-318.

13. Greenberg, Clement. “Avant-Garde and Kitsch.” Partisan Review. 6:5 (1939): 34-49.

14. Handa-Gagnard, Astrid. “Voyage through the Void: Nouveau Realisme, the Nature of Reality, the

Nature of Painting,” in Destroy the Picture: Painting the Void, 1949-1962. Edited by Paul Schimmel. Los

Angeles: The Museum of Contemporary Art, 2012. Pp. 212-223.

15. Huyssen, Andreas. “The Cultural Politics of Pop: Reception and Critique of US Pop Art in the Federal

Republic of Germany,” New German Critique. 4 (Winter 1975): 77-97.

16. Lobel, Michael. “F-111,” in James Rosenquist: Pop Art, Politics, and History in the 1960s. Berkeley:

University of California, 2009. Pp. 123-153 and 183-191.

17. Meyer, Richard. “Warhol’s Clones,” Yale Journal of Criticism. 1 (1994): 79-109.

18. Orton, Fred. “A Different Kind of Beginning,” in Figuring Jasper Johns. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press, 1994. Pp. 89-146.

19. Schwabsky, Barry. “Sheer Sensation: Photographically-Based Painting and Modernism,” in The

Painting of Modern Life: 1960s to Now. London: Southbank Centre, 2007. Pp. 26-31.

20. Silverman, Kaja. “Photography by Other Means.” in The Painting of Modern Life: 1960s to Now.

London: Southbank Centre, 2007. Pp. 18-25.

21. Steinberg, Leo. excerpt from “Other Criteria: The Flatbed Picture Plane.” [based on a lecture given at

the Museum of Modern Art, March 1968]

22. Ziegler, Ulf Erdman and Kai-Uwe Hemken. “The Sons Die before the Fathers,” German Art from

Beckmann to Richter: Images of a Divided Country.” Edited by Eckhart Gillen. Cologne: DuMont

Buchverlag : Berliner Festspiele GmbH : distributed by Yale University Press, 1997. Pp. 374-403.

8

RUBRIC FOR ART HISTORY

adapted from written communication rubric developed by the Association of American Colleges & Universities

Context & Purpose

for

Writing

(x1)

Understands the topic

Content

Development (x4)

Clear, well-developed

essay

Genre & Disciplinary

Conventions/

Control of

Syntax & Mechanics

(x3)

Accepted rules for

academic writing

Use of ClassAssigned Readings

(x4)

Use of Art Works

Shown in Class

(x4)

Student’s Position

(perspective,

thesis/hypothesis)

(x4)

Follows Instructions

COMMENTS

JAW-DROPPING 5

MASTERFUL 4

PROFICIENT 3

DEVELOPING 2

At the beginning of the

essay, clearly

communicates a

thorough understanding

of the assigned task and

gives a clear statement

of approach to

answering the

assignment.

Uses appropriate,

relevant, and compelling

content to show mastery

of the assigned task

throughout the essay.

Communicates

adequate

understanding of the

assigned task and

gives a clear statement

of approach to

answering the

assignment.

.

Uses appropriate,

relevant, and engaging

content to explore

ideas pertaining to

assigned task

throughout the essay.

Demonstrates

consistent use of

important academic

conventions, including

organization, content,

presentation,

formatting, citations

and stylistic choices.

Uses straightforward

language that

generally conveys

meaning to readers.

The language has few

errors.

Demonstrates use of

course readings and

relevant sources to

support ideas that are

situated within the

discipline and genre of

the writing.

Communicates

awareness of the

assigned task and

gives a general

description of

approach to

answering the

assignment.

Communicates

minimal attention to

the assigned task

with few to no details

of approach to

answering the

assignment.

Uses appropriate and

relevant content to

develop and explore

ideas through most of

the work.

Uses appropriate

and relevant content

to develop simple

ideas in some parts

of the work.

Follows expectations

appropriate to

academic

conventions for basic

organization, content,

citations and

presentation. Uses

language that

generally conveys

meaning to readers

with clarity, although

writing may include

some errors.

Attempts to use a

consistent system for

basic organization

and presentation.

Uses language that

sometimes impedes

meaning because of

errors in usage.

Demonstrates an

attempt to use course

readings and relevant

sources to support

ideas that are

appropriate for the

discipline and genre

of the writing.

Demonstrates an

attempt to use

credible and/or

relevant art works to

support ideas that are

appropriate for the

assignment.

Demonstrates an

attempt to use

sources to support

ideas in writing.

Specific position

(perspective,

thesis/hypothesis)

asserted with

different sides of an

issue acknowledged.

Specific position

(perspective,

thesis/hypothesis) is

stated but is

simplistic and

obvious.

Demonstrates detailed

attention to

and successful execution

of academic

conventions, including

organization, content,

presentation, formatting,

citations and stylistic

choices. Uses graceful

language that skillfully

communicates meaning

to readers with clarity

and fluency and is

virtually error-free.

Demonstrates skillful use

of course readings and

other high quality,

credible, relevant

sources to develop ideas

that are appropriate for

the discipline and genre

of the writing.

Demonstrates innovative

and skillful use of a

variety of relevant art

works to develop ideas

that are appropriate for

the assignment and the

student’s approach to it.

Specific position

(perspective,

thesis/hypothesis) is

imaginative, taking into

account the complexities

of an issue. Limits of

position (perspective,

thesis/hypothesis) are

acknowledged. Others’

points of view are

synthesized within

position (perspective,

thesis/hypothesis).

Turns in on time; proper

essay format; proper

citation format; name

only on rubric

(5 pts deducted per item.

25 pts deducted if late)

Demonstrates

consistent use of a

variety of relevant art

works to support ideas

that are appropriate for

the assignment and

the student’s approach

to it.

Specific position

(perspective,

thesis/hypothesis)

takes into account the

complexities of an

issue. Others’ points of

view are

acknowledged within

position (perspective,

thesis/hypothesis).

FLOP

0

Demonstrates an

attempt to use art

works to support

ideas in response to

the assignment.

Late

SCORE

9

Universal Intellectual Standards by Linda Elder and Richard Paul

Universal intellectual standards are standards which must be applied to thinking whenever one is interested in checking

the quality of reasoning about a problem, issue, or situation. To think critically entails having command of these standards.

To help students learn them, teachers should pose questions which probe student thinking, questions which hold students

accountable for their thinking, questions which, through consistent use by the teacher in the classroom, become

internalized by students as questions they need to ask themselves.

The ultimate goal, then, is for these questions to become infused in the thinking of students, forming part of their inner

voice, which then guides them to better and better reasoning. While there are a number of universal standards, the

following are the most significant:

CLARITY: Could you elaborate further on that point? Could you express that point in another way? Could you give me an

illustration? Could you give me an example?

Clarity is the gateway standard. If a statement is unclear, we cannot determine whether it is accurate or relevant.

In fact, we cannot tell anything about it because we don't yet know what it is saying. For example, the question,

"What can be done about the education system in America?" is unclear. In order to address the question

adequately, we would need to have a clearer understanding of what the person asking the question is considering

the "problem" to be. A clearer question might be "What can educators do to ensure that students learn the skills

and abilities which help them function successfully on the job and in their daily decision-making?"

ACCURACY: Is that really true? How could we check that? How could we find out if that is true?

A statement can be clear but not accurate, as in "Most dogs are over 300 pounds in weight."

PRECISION: Could you give more details? Could you be more specific?

A statement can be both clear and accurate, but not precise, as in "Jack is overweight." (We don't know how

overweight Jack is, one pound or 500 pounds.)

RELEVANCE: How is that connected to the question? How does that bear on the issue?

A statement can be clear, accurate, and precise, but not relevant to the question at issue. For example, students

often think that the amount of effort they put into a course should be used in raising their grade in a course. Often,

however, the "effort" does not measure the quality of student learning, and when this is so, effort is irrelevant to

their appropriate grade.

DEPTH: How does your answer address the complexities in the question? How are you taking into account the problems

in the question? Is that dealing with the most significant factors?

A statement can be clear, accurate, precise, and relevant, but superficial (that is, lack depth). For example, the

statement "Just say No" which is often used to discourage children and teens from using drugs, is clear, accurate,

precise, and relevant. Nevertheless, it lacks depth because it treats an extremely complex issue, the pervasive

problem of drug use among young people, superficially. It fails to deal with the complexities of the issue.

BREADTH: Do we need to consider another point of view? Is there another way to look at this question? What would this

look like from a conservative standpoint? What would this look like from the point of view of...?

A line of reasoning may be clear accurate, precise, relevant, and deep, but lack breadth (as in an argument from

either the conservative or liberal standpoint which gets deeply into an issue, but only recognizes the insights of

one side of the question.)

LOGIC: Does this really make sense? Does that follow from what you said? How does that follow? But before you implied

this and now you are saying that; how can both be true?

When we think, we bring a variety of thoughts together into some order. When the combinations of thoughts are

mutually supporting and make sense in combination, the thinking is "logical." When the combination is not

mutually supporting, is contradictory in some sense, or does not "make sense," the combination is not logical.

www.criticalthinking.org

Copyright©Foundation for Critical Thinking

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED