The Cradle of a Nation by John Rule - Metaldetector-RJ

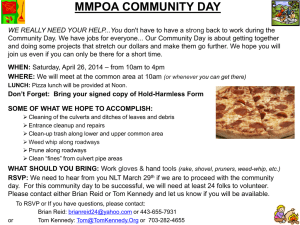

advertisement