Feedback in this Policy

advertisement

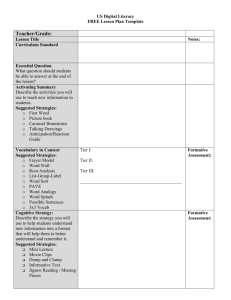

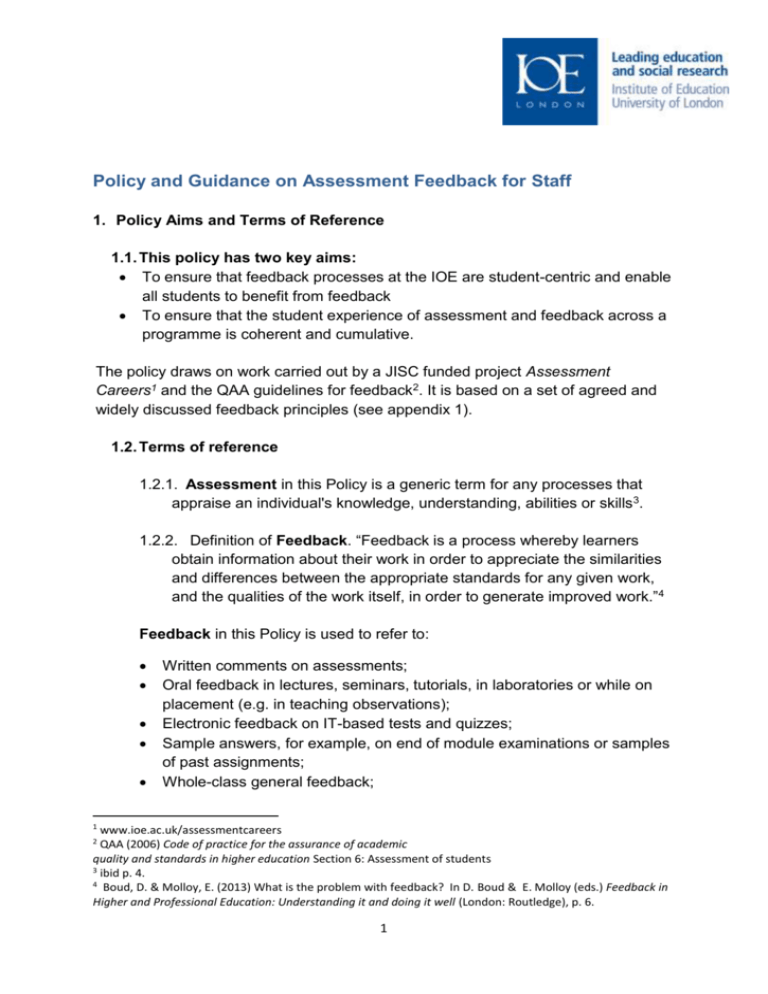

Policy and Guidance on Assessment Feedback for Staff 1. Policy Aims and Terms of Reference 1.1. This policy has two key aims: To ensure that feedback processes at the IOE are student-centric and enable all students to benefit from feedback To ensure that the student experience of assessment and feedback across a programme is coherent and cumulative. The policy draws on work carried out by a JISC funded project Assessment Careers1 and the QAA guidelines for feedback2. It is based on a set of agreed and widely discussed feedback principles (see appendix 1). 1.2. Terms of reference 1.2.1. Assessment in this Policy is a generic term for any processes that appraise an individual's knowledge, understanding, abilities or skills3. 1.2.2. Definition of Feedback. “Feedback is a process whereby learners obtain information about their work in order to appreciate the similarities and differences between the appropriate standards for any given work, and the qualities of the work itself, in order to generate improved work.”4 Feedback in this Policy is used to refer to: Written comments on assessments; Oral feedback in lectures, seminars, tutorials, in laboratories or while on placement (e.g. in teaching observations); Electronic feedback on IT-based tests and quizzes; Sample answers, for example, on end of module examinations or samples of past assignments; Whole-class general feedback; 1 www.ioe.ac.uk/assessmentcareers QAA (2006) Code of practice for the assurance of academic quality and standards in higher education Section 6: Assessment of students 3 ibid p. 4. 4 Boud, D. & Molloy, E. (2013) What is the problem with feedback? In D. Boud & E. Molloy (eds.) Feedback in Higher and Professional Education: Understanding it and doing it well (London: Routledge), p. 6. 2 1 Peer feedback, either formally as part of an assessment task or informally outside of the classroom; Self-reflections and self-critique. ‘ 1.2.3. Feedback can be provided during or following both formative and summative types of assessment, the definitions of which are provided below: 1.2.4. Formative Assessment is designed to provide learners with feedback on progress and inform development. It can occur informally during teaching sessions or be part of a more formal process of submission of draft assignments. 1.2.5. Summative Assessment provides a measure of achievement or failure in respect of a learner’s performance in relation to the assessment criteria and standards 2. Policy Rationale and Policy Statements Students in higher education need to be self-regulating, that is able to manage their learning, make use of feedback from a range of sources and plan their learning5 While some of our students begin their programme of study with the assessment literacy and confidence to engage in dialogue with academic staff and peers about their work, not all are familiar with, or prepared for, such a student-centric approach. Making judgements about a piece of work and seeing how to improve it is a cognitively demanding task. We cannot assume that all students will acquire the skills to learn from assessment throughout their programme and assessment literacy needs to be developed as part of the curriculum. Research is beginning to show that this can be achieved through giving student early and repeated formative assessment opportunities where they compare self-assessments to assessments made by peers and/or by teachers and learn to become assessors themselves 6. 2.1. Students have a responsibility to: 5 Nicol, D. & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006) Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education 31(2): 199-218. 6 Nicol, D. (2010) From monologue to dialogue: improving written feedback processes in mass higher education, Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 3 (5): 501-517. 2 Engage with feedback from a range of sources including self and peer feedback and both verbal and written to improve academic performance; Provide feedback to peers and assist others in their learning while avoiding plagiarism and respecting the confidentiality of feedback addressed to individuals; Plan action on feedback not only in the short term (e.g. when feedback is on draft work) but also in the longer term (e.g. for a future assignment); Understand that feedback from different sources may at times vary and that there may be more than one possible response to feedback; Engage in dialogue about their learning and progression and seek support if uncertain about how to action any feedback; Understand that not all response to feedback will lead to immediate improvement of grades which might require sustained effort over a longer time period; Over time to become increasingly independent and able to self-critique and reflect on work. 2.2. Teaching staff will: Provide information that is clear to all students about the nature of the feedback they will receive on particular assignments and activities and provide appropriate guidance on how students can progress; Include early formative assessment activities which engage students in feedback as part of teaching e.g. through peer or self feedback as well as feedback on drafts. See for example a dialogic process in appendix 2; Initiate dialogue with students to encourage reflection and future action planning and respond to request for feedback or for clarification as part of teaching activity. See for example the student feedback response form; Ensure that students have opportunities to apply feedback in both the short term and across the programme; Encourage learners to self-regulate their learning over time and reduce reliance on others; 3 Review programme team and module team feedback practice, resolve any major discrepancies in feedback to an individual from team members and make improvements to feedback arrangements where possible. A feedback analysis tool and guidelines are available for self review and team reviews of feedback; Where feedback is discussed in groups, respect the confidentiality of feedback addressed to individuals; Utilise scholarship, research and professional activities to develop feedback practice. 2.3. Departments, programme leaders and curriculum developers will: Ensure that workload models allow programmes teams and individuals time for discussing and planning feedback; Encourage the sharing of good practice in assessment through departmental meetings and staff development events; Adjust the volume and nature of assessment to reflect a context of enhanced feedback; Review curricula to ensure that coherent and cumulative assessment and feedback arrangements are considered explicitly in programme specification documents and programme reviews including both formative and summative assessment. Ensure that programme information makes explicit the role of, and type of, feedback that students will receive in order to manage student expectations; Provide information to students and to staff on the deadlines for the receipt and return of assessed work; Monitor implementation of the feedback policy through student evaluations and External Examiner comments to ensure that learners have a coherent assessment experience across programmes in the department. 2.4. Learning and Teaching and Quality Assurance staff will: Monitor student evaluations of feedback as part of programme annual and periodic reviews; Ensure that all validated programmes have a coherent assessment plan so that feedback can be cumulative across the programme; Provide staff development for assessment and feedback; Monitor implementation of the feedback policy to ensure that learners have a coherent and high quality assessment experience across programmes at the IOE as evidenced by student surveys and External Examiner comments; 4 Ensure that programme information makes explicit the role of, and type of, feedback that students will experience in order to manage student expectations. Policy drafted by Assessment Careers project leaders 17.1.14 5 · Appendix 1 Feedback principles, rationale, goals and examples 1. Feedback helps learners to self–evaluate their work Feedback that is given to students encourages passivity. To be able take future action, they need to understand the frame of reference of the assessor including tacit and explicit assessment criteria and standards. Peer and self review can be used to encourage learners to take a more active role in feedback with appropriate guidance from tutors. Reviewing the work of self or others puts students in the role of assessor and helps clarify not only assessment criteria but also more tacit disciplinary requirements. Systematic self-review helps students develop their ability to self-critique. Students have also reported that the act of giving feedback to peers helped them to understand both the assessment criteria and the quality of their own work. Institutional Goal: Feedback processes encourage learners to be active and self-reliant Example 1: Students are provided with a space on an assignment cover sheet to self–evaluate their work and request feedback. Students who are unsure about their feedback needs are given support on how to request useful feedback. Example 2: Students share their work online in an accessible forum and give peer feedback using agreed criteria. 2. Feedback enables students to address performance goals in both the shortterm and longer-term Students must understand how they can apply critique from one task or assignment to the next if they are to apply feedback as part of their learning. This means that feedback must address skills and processes such as academic writing and self-assessment skills and not only content. In other words there should be a good balance between feedback that addresses specific module assessment criteria and feedback that addresses disciplinary attributes and skills at the programme level. Institutional Goal: Feedback addresses longer-term programme level learning as well as short-term goals 6 Example 1: Students are provided with a) critique on the content of the current piece of work and advice on how to improve it in the short-term, and b) suggestions or prompts that will help with future module assignments too, such as how to develop research or academic writing skills. 3. Feedback includes dialogue (peer to peer and teacher-student) Dialogue with assessors and peers helps students to clarify feedback in relation to assessment criteria and standards and to be able to take action. Assessors and/or peers can initiate dialogue by asking direct questions to the student. If a systematic method is set up so that students can respond to feedback or questions, then the conversation can continue. Where possible, opportunities for dialogue should be built into the programme. Institutional Goal: Assessment processes are designed so that students have opportunities for dialogue about feedback Example 1: Students complete a reflection on their previous feedback and state how they have addressed the points made and submit this with the assignment. Students who are unsure how to complete the reflection are supported. A dialogue continues either verbally or written and assessors comment on the actions students have taken and assessors suggest future action or goals if necessary. Example 2: Feedback from peers or tutors contains questions and prompts reflection rather than provides answers. The student discusses their reflection with peers or in a tutorial which could be online. 4. Learners have opportunities to apply previous feedback In a modular scheme it can be difficult for both learners and tutors to judge a learners’ progress across a programme other than by referring to module grades, but grades do not give a detailed picture. When students build on previous learning in a structured way, student progress or any concerns about progress can be made visible. Assignments which build upon previous assignments give students opportunities to act on previous feedback. Both learners and assessors can use this information to judge the next steps, and if difficulties are not being addressed from one module to the next, then this can be picked up early on. 7 Institutional Goal: Assessments build on other assessments and so feedback can be cumulative over time Example 1: A Research Methods module is used to develop a dissertation proposal using feedback. Example 2: Students apply feedback on teaching observations across a programme . 5. Feedback is motivational for all students Feedback can be categorised in terms of praise, recognition of progress, critique, questions and advice for future development. Each category of feedback has a different purpose and both assessors and students need to be clear on the purposes of feedback in different contexts. The appropriate balance between the different types of feedback can be discussed between programme teams and with students using a tool designed for feedback analysis. For example, students may like praise, but they find tailored advice and questions that prompt their thinking to be more helpful and motivational for learning in the longer term. Institutional Goal: The purpose of feedback is shared and discussed by programme teams. Example 1: A programme team held a meeting to discuss research on feedback and the limited effectiveness of praise. The team now plans to increase the amount of advice and recognition of progress that they provide for students and decrease praise. 6. Students have frequent formative assessment opportunities Formative assessment is essential for learning as it focuses student time and attention on appropriate learning activities and leads to greater achievement. Students will benefit if they receive formative feedback early. Formative feedback on draft assignments may not be submitted until well into a module, but early formative activities can be designed into modules to encourage students to spend time preparing for the assignment. With appropriate guidance the feedback can be from peers. Institutional Goal: Programmes are designed to include frequent formative assessment opportunities 8 Example 1: Students write a 500 word piece of early writing and discuss this with peers or a tutor. They then apply the feedback to enhance this piece of work, or to write for a longer assignment. Further Reading Carless, D. Slater, D.Yang, M. and Lam, J. (2011) Developing sustainable feedback practices. Studies in Higher Education 36, no.4: 395-407. Hattie, J. & Timperley, H. (2007) The Power of Feedback. Review of Educational Research 77 no. 1: 81-112. Hughes, G. (2011) Aiming for Personal Best: a Case for Introducing Ipsative Assessment in Higher Education Studies in Higher Education 36 (3): 353 – 367. Nicol, D. & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006) Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education 31 no. 2: 199-218. Drafted by the Assessment Careers Project Team www.ioe.ac.uk/assessmentcareers Updated November 2013 Please send requests for clarification to g.hughes@ioe.ac.uk 9 Appendix 2 Example of dialogic feedback cycles Student makes 1st formative attempt at task Student gets feedback from peer assessment Student makes 2nd formative attempt at task Student gets feedback from self-assessment Student makes 3nd formative attempt at task Student gets feedback from tutor assessment Student makes summative attempt at task Student receives grade and feedback for the future 10