Free morphemes are units of meaning which cannot be split into

advertisement

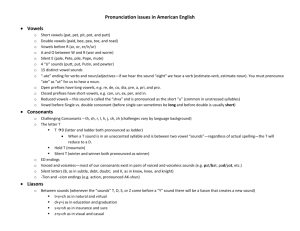

Phonology 1 Phonology is the study of the sound patterns of language. It is concerned with how sounds are organized in a language. Phonology examines what occurs to speech sounds when they are combined to form a word and how these speech sounds interact with each other. It endeavors to explain what these phonological processes are in terms of formal rules. The amazing discovery is that people systematically ignore certain properties of sounds. They perceive two different sounds as the same sound. We call the stored versions of speech sounds phonemes. Thus phonemes are the phonetic alphabet of the mind. That is, phonemes are how we mentally represent speech; how we store the sounds of words in our memory. Though the phonetic alphabet is universal (we can write down the speech sounds actually uttered in any language), the phonemic alphabet varies from language to language. For example, English has no memorized front rounded vowels like German or French, and French has no [θ]. This leads to seemming contradictions when we consider both actual productions 2 of speech sounds as well as their memorized representations. English has no memorized nasal vowels, but English speakers do make nasalized vowels when vowels and nasal consonants come together in speech. The changes between memory and pronuciation are what we will be discovering in this section of the course The fact that speakers have a mental representation of what they say, and that this can be different from what they actually do when they speak, shows us that speakers do not memorize every aspect of speech sound production. Only the essential (contrastive, phonemic) features are stored in memory. Other features (specifics of pronunciation) are added during speech planning and production. Predictable information about speech is not memorized. Predictable features are added by rules of pronunciation (phonological rules). English speakers pronounce vowels either with the velum closed (oral) or with the velum open (nasal). By careful listening or experimental investigation, we can determine that the velum is open during the entire production of the word "man": [mæ̃n] In contrast, speakers do not have the velum open at all in the production of the word "bat": [bæt] Most important, however, is that English speakers perceive that both "man" and "bat" have the same vowel. That is, English speakers are ignoring the difference in nasality between the two words. English speakers feel that this difference in nasality is unimportant for recognizing a word in their memory. We can understand this behavior through understanding that speakers memorize vowels without the feature [nasal]. English speakers believe that there are no nasal vowels in English, at least for the purpose of memorizing words. The reason for this is that in English nasality in vowels is predictable. In English, nasal vowels only occur before nasal consonants. Everywhere else English speakers use oral vowels. Therefore [nasal] is predictable for English vowels, and is governed by a rule of pronunciation: 3 Vowels become nasal when a nasal consonant immediately follows. [vowel] → [nasal] / _ [nasal, consonant] We call the mental representation a phoneme, and we call the distinct pronunciations allophones. The predictable aspects of pronunciation (here [nasal] in vowels) are added by the rules in the phonology of the language. The rules of pronunciation determine the variants in speech sounds. This particular rule makes one sound (the vowel) more similar to an adjacent sound (the following nasal consonant), by making the vowel [nasal]. Rules that make sounds more similar are called assimilation rules. Rules that make sounds less similar are called dissimilation rules. Assimilation rules are much more common than dissimilation rules. Which features are predictable varies from language to language. In French speakers must memorize [+nasal] for vowels because in French this is important for the meaning of the word. That is, French has minimal pairs for nasality in vowels. Within a single sound some of the aspects of speech sound production (features) may be predictable from the other features. Here are some examples from English: All nasals are voiced: [nasal] → [voiced] all high back vowels are round: [vowel, high, back] → [rounded] all front vowels are not round: [vowel, front] → [unrounded] These particular rules are rules of English. Other languages may or may not have these rules. So, for instance French has frount rounded vowels, but no high back unround vowels. Russian has the reverse: high back unround vowels but no front round vowels. Turkish has both front round vowels and high back unround vowels. All languages impose certain restrictions on the sequences of sounds in the language. Some languages like to alternate consonants and vowels. These language do not allow sequences of consonants nor sequences of vowels. There are two possible responses a language can make to an unwanted sequence. One is to change one of the sounds, through a rule. This is what we observed with English nasal 4 vowels. Oral vowels are not allowed to be followed by nasal consonants, so the vowel is changed to be nasal. The other possible response is to simply ban the sequence from words as they are stored in memory. In English there is a general ban on words beginning with *[tl] and *[dl], even though words starting with [pl], [bl], [kl] and [gl] are fine. But there is no general rule to repair these bad sequences. It is also possible to have the situation where sound that are memorized differently are nevertheless pronounced identically under certain circumstances. Consider the pronuncation of the vowels in these two words: [tɛləgræf] "telegraph" [təlɛgrəfi] "telegraphy" But since both of these words involve the same morpheme, meaning "telegraph", this morpheme must have the same memorized representation, namely, /tɛlɛgræf/ Therefore the changes in pronunciation are insignificant for memory here, and must be due to a rule of pronunciation. The rules is very simple, unstressed vowels reduce to schwa in English. [vowel, unstressed] → [ə] [vowel, unstressed] → [mid, central, unrounded, plain] 5 Morphology 6 Morphology is the study of the structure and form of words in language or a language, including inflection, derivation, and the formation of compounds. At the basic level, words are made of "morphemes." These are the smallest units of meaning: roots and affixes (prefixes and suffixes). Native speakers recognize the morphemes as grammatically significant or meaningful. For example, "schoolyard" is made of "school" + "yard", "makes" is made of "make" + a grammatical suffix "-s", and "unhappiness" is made of "happy" with a prefix "un-" and a suffix "-ness". Inflection occurs when a word has different forms but essentially the same meaning, and there is only a grammatical difference between them: for example, "make" and "makes". The "-s" is an inflectional morpheme. In contrast, derivation makes a word with a clearly different meaning: such as "unhappy" or "happiness", both from "happy". The "un-" and "-ness" are derivational 7 morphemes. Normally a dictionary would list derived words, but there is no need to list "makes" in a dictionary as well as "make." EXAMPLES • A free morpheme is a unit of meaning which can stand alone or alongside another free or bound morpheme. • These are usually individual words, such as lid sink air car • A bound morpheme is a unit of meaning which can only exist alongside a free morpheme. • These are most commonly prefixes and suffixes: ungrateful insufficient childish USE • A knowledge of morphology creates an awareness of meaning at a sub-lexical level. That is, we can deconstruct a word and consider its component parts. • The stems, roots, prefixes, and suffixes of words can be recognised. This can throw light on etymology (the origins of the word) thus giving us more power to communicate efficiently. • Free morphemes are units of meaning which cannot be split into anything smaller, as in the following examples: tree gate butter rhinoceros • However, the terms 'gate', 'butter' and 'flower' can also exist alongside another free morpheme. The following examples comprise two free morphemes gatepost buttermilk sunflower • Bound morphemes are also units of meaning which cannot be split into anything smaller. However, they are different from free morphemes because they cannot exist alone. They must 8 be bound to one or more free morphemes. Almost all prefixes and suffixes are bound morphemes. Prefixes asymmetrical, subordinate, unnecessary Suffixes cowardice, minty, fruitful, swimming • The following words are made up of two free morphemes or components which could stand alone and retain their meaning. inkwell mothball sunflower slapstick • Note that morphemes can only be classified according to their given semantic context. • Take for example the word 'elephant' which is a free morpheme. Although it is a lengthy word, it cannot be split up into any smaller units of meaning within this particular context. That is, the word 'elephant' refers to a large grey mammal with a trunk and tusks which is indigenous to India and Africa. • The final three letters of elephant may spell 'ant', but that unit of meaning does not exist in the context of the term 'elephant'. • Now take the word 'ant' as a separate unit of meaning referring to a small insect. In that context 'ant' is a free morpheme. Add another free morpheme in the form of 'hill' and we have a word comprising two free morphemes - 'anthill'. • The unit 'ant' can also be classified separately as a bound morpheme in yet another context. The term 'ant' can act as a prefix in the word 'antacid'. As such, it is a bound morpheme because its meaning only exists in conjunction with the free morpheme 'acid'. 9 Syntax 10 Syntax is the arrangement of words in sentences, clauses, and phrases, and the study of the formation of sentences and the relationship of their component parts. In a language such as English, the main device for showing the relationship among words is word order; e.g., in “The girl loves the boy,” the subject is in initial position, and the object follows the verb. WORDS The basis of the sentence is the word. However, words can be broken up into many different categories and sections. Firstly, words can be broken down into roots and suffixes. There are again two forms: Inflectional forms are mainly verbs. For example, the word laugh is the root of quite a few words. The suffixes -s, -ed and -ing can be added to make the words laughs, laughed and 11 laughing respectively. These words are all of the same basic structure because they are all verbs and operate in a similar way. Derivational forms are words that completely alter meaning and using by the addition of a suffix. For example, the word 'friend' is a noun. With the addition of the suffix -ly it becomes 'friendly', which is an adjective. It can become more complex still with the addition of -liness to make 'friendliness'. All of these words are based on the same root but all operate in completely different ways. Once the word has been formed, it can still be split into many categories. Closed classes of words are things like articles and pronouns. This class of word is never likely to alter much. The same articles have been used for many years and it is very rare that any new ones will be introduced. However, the open class of words (containing mainly nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs) can be changed on a regular basis. For example, new slang words are often used that through constant use find themselves entering the language. A good example of this is Shakespeare. Shakespeare, invented nearly two thousand words that are now in common usage in the English language. He introduced us to 'critical', 'countless', 'excellent', 'gust', 'hint', 'lonely' and 'dwindle' amongst others. Once words have been split into all of these categories, they can then be broken down into the regular subsections such as nouns, verbs and adjectives. Unfortunately, many words are irregular, not sticking to the general rules and being ambiguous. The categories for words can overlap. All of these factors combine to make the understanding of words in the English language very difficult. For a computer to process natural language, not only does it have to have thousands of words in it`s dictionary, but it also needs to know how and where all of these words can be used and into which category each one falls. PHRASES AND SENTENCES 12 Once words have been formed, these can then be combined. The easiest thing they can combine into is the phrase. This is just a collection of words together and again breaks down into many categories. The head of a phrase (i.e. the most important word in the phrase) is an open class word. This is therefore usually a noun or verb or adjective, and thus leads to noun phrases, verb phrases etc. NOUN PHRASES The main part of a noun phrase is, quite unsurprisingly, a noun. This is known as the head of the phrase. It is the main subject of the phrase. In addition to this, the phrase may also contain a specifier and a qualifier. A specifier can have a number (e.g. one, two, first, second) and a determiner. A determiner can be words such as 'a', 'this', 'that', 'which', 'what', 'her', 'my', -'s (e.g. Tom's), 'some', 'most' or 'any'. The specifier therefore states how many there are of the noun and how it relates to the reader and writer. A qualifier comes after the specifier and consists of a descriptive word (usually an adjective) that modifies the noun. An example of a noun phrase is: VERB PHRASES 13 Verbs, unfortunately, are extremely difficult to process. This is due to the large amount of forms and tenses and irregularity of verbs. There are a lot of different tenses that verbs can take. The verb phrase consists of a verb in one of these tenses and its complements. Some verbs (known as modal verbs) take a further verb phrase as their complement which can lead to a string of verbs. Examples of modal verbs are things such as 'will', 'can' and 'could'. E.g. "Tom will work", "Paddy can play". When the verb phrase has a noun phrase as its complement, this leads to the simple sentence "He hits the annoying man." Together, the noun phrases and verb phrases make up the basis of the sentence. In order to generate more complex sentences it is necessary to go into more depth on syntax. If you require further information, please refer to the bibliography. WORTH TO SEE:______________________________________________________________ http://angli02.kgw.tu-berlin.de/html/morpholo.html/ http://www.utexas.edu/courses/linguistics/resources/syntax/index.html http://www.ic.arizona.edu/~lsp/Phonology.html http://www.enjoywords.com/English_morphology.html 14 http://www.ncl.ac.uk/elll/research/language/syntax.htm http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=5000563304&gserror=true http://www.sil.org/linguistics/GlossaryOfLinguisticTerms/WhatIsPhonology.htm http://www.sil.org/linguistics/Linguistics.htm http://www.coli.uni-saarland.de/~kris/nlp-with-prolog/html/node20.html http://www.sil.org/pckimmo/v2/doc/englex.html WORTH TO READ:____________________________________________________________ What Is Morphology? by Mark Aronoff, Kristen Fudeman Morphology (Palgrave Modern Linguistics) by Francis Katamba, John Stonham Optimality Theory in Phonology by John McCarthy An Introduction to Phonetics and Phonology by John Clark, Colin Yallop, Janet Fletcher 15 Syntax: A Generative Introduction by Andrew Carnie 16