Artifact One – RE 5100 Final Exam

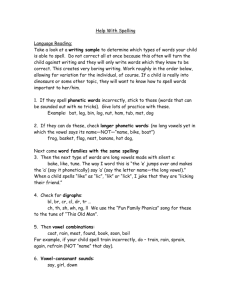

advertisement

Question #1 John is currently in the phonetic stage. One justification for this is that his spellings have a good representation of beginning and ending consonants. For example, in the word “back,” he wrote the “b” for /b/ and the “c” for /k/. Secondly, he has not learned to mark long vowel sounds. One example is his spelling of “side,” leaving off the “e.” Thirdly, John uses phonologically appropriate substitutions when representing short vowels, as seen in his use of the letter “a,” instead of “e,” when spelling “step” and “dress.” Next, he is not able to correctly represent consonant blends and digraphs. An example would be his spelling of “step” when he uses the letter “s,” but does not include the “t.” Based on his spelling errors, it would be appropriate to engage him in word study at the level of short vowels using word families. He can hear the consonant sounds, but made frequent errors in his use of short vowels, employing phonologically appropriate substitutions. Since short vowel sounds are frequent in English and they are fairly regular in their letter/sound mapping, working with the short vowels using word families with give him practice in representing the various short vowel sounds with the appropriate letters. Sue is in the pre-phonetic stage. Justification for this is seen in the fact that she did not include vowel sounds in her spellings, using consonants only. Secondly, she can justifiably represent beginning sounds in words. With words such as “picking” & “peeked,” she represented the first sound /p/ with the letter “p,” but included no other letters. Thirdly, with words such as “side” or “dress,” she justifiably uses the soft “c” sound or the /j/, respectively, to spell the initial sound she hears. Lastly, she has begun to move beyond hearing just beginning consonants & can hear some ending consonants as well, as in “bk” for “back” or “ft” for “feet.” Sue would benefit from continued work on the consonant sounds because she still occasionally makes mistakes in correctly representing initial consonant sounds & she has not gotten to the point where she can consistently hear consonant sounds that occur later in a word’s spelling. Hannah is in the vowel transition stage. One reason for placing her in this stage is her ability to spell short vowel sounds in most words correctly, as in her use of the short /i/ when spelling “picking.” Secondly, she has learned to use markers when representing long vowel sounds, although she sometimes does not use the correct one, as in spelling “feet” as “fete.” Thirdly, she inconsistently uses standard spellings of digraphs, such as when she uses “ck” to spell “back,” but only uses “k” in “picking.” Lastly, she knows some standard word endings, such as “-ing” in “picking” but not “-ed” when spelling “peeked.” Hannah should work with mixed vowel patterns because she already knows how to represent short vowels, but needs to work on correctly representing frequently-occurring long vowel patterns. Given in January, this test would be a good predictor of end-of-first-grade reading achievement. John could potentially be on-grade level by being able to read short vowel words with/without blends or digraphs since he can already hear beginning & ending consonants, as well as vowel sounds (although not necessarily spelling them correctly). His reading material for the rest of the year would require some repetition, word control, & structure in order to develop automaticity in his recognition of various spelling patterns & sight words. Hannah, however, is already able to pick up on variations in spelling patterns (such as representing long vowel sounds) &, therefore, has the potential to end the year above grade level. Her abilities allow her to decode new words with different spelling patterns & minimal repetition. Question #2 A first-grade phonics curriculum consists of three main stages. The first stage deals with beginning consonants. Students should learn to hear the beginning sound in words and then be able to assign a consonant to that sound. This is logical because the easiest sound for children to hear is the beginning consonant in a word. After that, they gradually begin to be able to hear the final consonant and then the intervening letters. The second stage deals with short vowels, both in word families and patterns. In word families, the students basically work with rhyming words. Since the students already have a knowledge of beginning consonants upon moving to this stage, they are now given the opportunity to use this knowledge of consonants (a “known”) while also practicing the use of vowels (an “unknown”). By using rhyming words, the students can use their familiarity with a particular word, such as the guide word “cat,” to sort and read other words, such as “mat,” “cat,” etc. The second opportunity to work with short vowels deals with patterns. With patterns, the short vowel is the only sound within the word that stays the same. This moves beyond the use of rhyming words and focuses on the medial vowel sounds while the beginning and ending consonants, digraphs, or blends change. This is more difficult because the students can no longer rely on the rhyming aspect to figure out the words, but they have to sort based on the medial vowel and attend to the beginning, middle, and ending sound in order to say the word. The third stage deals with mixed vowel patterns. This consists of short, long, and r-controlled vowels. Because of the students’ work with short vowels in the previous stage, this gives students the opportunity to contrast the “known” (short vowels) and the “unknown” (long vowels and r-controlled vowels). This is also a logical next step because, whereas the short vowels are generally regular in their letter/sound mapping, the long vowel sounds have more variability in their spellings and the vowels that are r-controlled are not as easy to hear because of their “distortion” from the sound they would have as individual letters. Word games, such as Memory and Bingo, and instructional-level reading both have a role to play in building word pattern knowledge. The word games, by their very nature, are motivational for the students because they are enjoyable to play. This increased motivation provides an incentive for the students to practice the particular area in word pattern knowledge being covered. After all, students do like to win at games, so it is logical that they would put forth a valiant effort to do their best at correctly applying what they know in order to sort and/or read words correctly in these games. Instructional-level reading plays a part in building word pattern knowledge because it presents students with texts having an emphasis on the particular concept with which they are working. For example, if a student is working with short vowels, the text would present numerous opportunities to practice reading words containing short vowels. There would be a controlled vocabulary, much repetition, and high frequency or sight words so that the student could feel successful and devote energy to decoding words that fall into the pattern being practiced, instead of becoming frustrated in stumbling across words he/she felt were indecipherable, thus losing motivation and meaning in the text as well. Both the word games and the instructional level reading help in developing automaticity or fluency when working with word patterns. The teacher determines whether to continue at the same phonics level or to move forward to the next level based on the degree of mastery the student demonstrates at the current level. If the student is not increasing in his/her accuracy and speed of responses in activities such as column-sorting or the word games, it is an indication he/she needs more work at the current level. On the other hand, increased speed and accuracy are indicative that the student is mastering the current level and may be ready to move on. It is also important for the teacher to notice if the child is able to read and spell new words following a particular pattern that is being studied. If the child is able to do so, it is further indication that the child is transferring the knowledge to other words, thus serving as a clue that the child may be ready to move on. Lack of transference regarding the particular pattern to new words is a sign that the child needs further practice in order to fully grasp what is being covered at the current level. The child’s level of frustration should also be noted. A high level of frustration indicates difficulty on the part of the child and is indicative that the child is spending too much mental energy on deciphering the task at hand and needs further practice in order to develop automaticity and fluency at the current level. Question #3 It is important for kindergarten and first-grade teachers to have a program for directly teaching meaning vocabulary for a few reasons. First of all, a strong relationship exists between vocabulary growth at an early age and later reading competence. Since kids in the primary grades are mostly unable to read content themselves that increases their vocabulary, this necessitates that it has to come from nonprint sources, such as parents, teachers, friends, television, etc. Secondly, if the children do not develop this meaning vocabulary by the time they reach the upper elementary grades, they will typically not fare well when they are expected to read expository texts. Even though they may be able to decode words, they will not be able to comprehend the text because they do not know what the words mean. Thirdly, some students are not exposed to as many opportunities for vocabulary growth at home due to situations involving the family’s socioeconomic status. Put quite simply, students from a poor, rural school would be much less likely to have a strong vocabulary than their peers from a rich, suburban school due to the amount of words spoken to them at home. Considering this inequity in vocabulary development based on home situation, it is vitally important for primary grade teachers to talk with, discuss, & read to their students to develop vocabulary. The main resource for teaching vocabulary to young children is reading text to them that contains new vocabulary & then discussing and clarifying the new vocabulary. This is necessary because the young child’s ability to make sense of meaning from context is limited. It is also necessary because text that contains such new vocabulary is probably not within the child’s reading level. It is, therefore, necessary for it to be read to them and they should then be given opportunities to understand the word’s meaning by asking questions, being provided with examples, etc. Routman’s classroom reading program might be an excellent context for helping children develop meaning vocabulary because during her whole group shared experiences, she was exposing the students to a variety of literature (beyond what they could read themselves) and engaging them in questioning and discussions to assess background knowledge, clarify meanings, check comprehension, etc. Question #4 Struggling first-grade readers are so at-risk in today’s educational system because there is such an emphasis on reading today in order to be successful in school. As Slavin indicates, school success is akin to being successful in reading. With the emphasis on testing beginning in third and fourth grades, the students need to be able to read on grade level in order to handle the level of reading required by their grade and have a better chance of scoring well. If the student is not “caught” before falling too far behind, it is nearly impossible for him/her to catch up because engaging solely in classroom reading instruction does nothing to narrow the gap and, in fact, widens it. Therefore, it is important to identify these students as early as possible, such as at the beginning of first grade. One-on-one tutoring offers a better chance for success with struggling beginning readers than does small-group instruction for a variety of reasons. First of all, the instruction can be tailored to the needs of the individual student. This involves what information is taught and how it is presented. This information can also be presented so as not to be too hard nor too easy. Tutoring of this type allows for prompt reinforcement and feedback as the child is learning. Working one-on-one allows for more individual time for instruction and practice so that the information can be learned. Lastly, there is an opportunity for more of an interpersonal bond to develop between the tutor and tutee which can serve to support learning. The critical factor in ensuring the success of paraprofessionals or community volunteers as reading tutors is the degree to which they receive supervision & support from a competent & skillful reading specialist at the school. This is true because the tutors will not necessarily have an understanding of the process of learning how to read & they will rely on the supervisor for guidance. Additionally, it is unlikely that tutors will know how to proceed step-by-step in planning instruction, including what methods & materials to use & how to use time most efficiently. The supervising reading teacher will be able to assist with these items. Lastly, having a school-based reading specialist as the tutors’ supervisor helps to ensure that this individual has had actual experience using the model being used for tutoring.