What is beauty? - Stanwich School

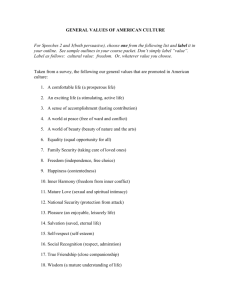

advertisement

Directions: With your group, answer the following questions and be ready to discuss: What is beauty? What are the positives and negatives of being “beautiful”? What struck you as the most interesting positive and negative? What do the ads say about the ideal of beauty and how it has changed over time? How did Rubens paint women? What was the ideal of the ancient Egyptians? Why was a pale look favored in Elizabethean England? What do the Paduang people of Asia do to change their appearance? What do some tribes in Africa do? What did the waist to hip ratio study show? What does the article say about facial beauty? What is the connection between wealth and weight? What does the formula mean: Adherence to social consensus + Genetic Fitness = Physical beauty? 10 Pleasures and Pains of Being Beautiful We may associate beauty with truth, but beauty is also threatening and sparks our defences. Beautiful people are all around us: on billboards, on TV and at the movies—some of them even inhabit our everyday lives. Great beauty in another person inspires all kinds of emotions: admiration, desire, hope, despair and sometimes envy. So what is the psychological effect of beauty and how do other people react to it? In fact being beautiful isn't all good, or so the psychological research suggests. Here are both sides of the coin, first five pleasures and then five pains of being beautiful. Five pleasures of being beautiful 1. What is beautiful is good In many situations we automatically defer to beauty, assuming that along with beauty come all sorts of other positive characteristics. We have a tendency to think beautiful people are funnier, more friendly, more intelligent, more exciting, in possession of better social skills, are sexually warmer, are more interesting, poised and even more independent. These sorts of judgements have been tested over-and-over again in the laboratory and elsewhere. This is a great example of the so-called 'halo effect': when global evaluations about a person bleed over into our judgements about their specific traits. 2. More desired There's a whole stack of research on mate selection and attractiveness. You won't find the headline result at all surprising: on pure looks alone we prefer partners who are more beautiful. Of course that assumes that everything else is equal, which it normally isn't. 3. Better persuaders Good-looking people make better persuaders (Chaiken, 1979). This may be because attractive people tend to be better communicators and possess more confidence or just because we believe in beauty. Whatever the reason, beauty can persuade us to change our minds. 4. Get paid more At work attractive people can receive all kinds of benefits. First of all they may get higher starting salaries, perhaps because their qualifications are perceived as more solid and their potential as greater (this is the halo effect workings its magic). Then, later on, they have an advantage in promotions. 5. Higher self-esteem Not surprisingly, given all the above advantages, goodlooking people also have higher self-esteem. What with all those dates and the extra money, is it any wonder they think better of themselves than their less fortunate peers? Five pains of being beautiful Now for the bad news about being beautiful. The beauty bias is probably not as strong as some have suggested and not as powerful as we might imagine (Eagly et al., 1991). For example, when it comes to income, in most lines of work it's better to be smarter than more attractive (Judge et al., 2009). The same goes for persuasion, self-esteem and even attraction: other personal qualities can easily trump beauty. Psychologists have also begun to uncover the dark side of being beautiful. Given what we already know about the beautiful it may be difficult to have much sympathy, but here are five pains: 1. Less likely to be hired (sometimes) Although beauty can help in the search for a job, it's not always true. When employers are making a decision about someone of the same sex, they can let their jealousy get the better of them. One recent study has suggested that people who are highly attractive are at a disadvantage in the hiring process when the decision-makers are the same sex (Agthe et al., 2011). It seems we perceive beautiful people who are the same sex as a threat. 2. Beauty is beastly Similarly there's evidence that female beauty can be a problem in jobs with strong gender stereotypes. For example a beautiful woman may be at a disadvantage when applying for a job which is associated with masculinity, like a prison guard or a mechanical engineer (Johnson et al, 2010). The same doesn't seem to be true for attractive men. They can happily apply for jobs as nurses, lingerie salespersons or HR managers without their beauty counting against them. 3. Perceived to be less talented The halo effect tells us that when we judge more attractive members of the opposite sex, we generally assume they're more talented than those who are less attractive. This happens even though what they do or say is no cleverer than less attractive people. But this changes when it's members of the same sex. In a study by Anderson and Nida (1978) highly attractive people of the same sex were judged as less talented than averagelooking people. 4. Lucky to be pretty If beautiful people are successful, is it because of their talent, or is it just their looks? After all, people are lucky to be beautiful and we know all the advantages of that. Research finds that when judging their own sex, people are more likely to think beautiful people's success is down to their beauty, not their talent (Forsterling et al., 2007). So you're lucky to be pretty, but probably just rely on that rather than talent. 5. Social rejection Although attractive people are generally more popular socially, there's some evidence that very attractive people can experience social rejection from members of their own sex (Krebs and Adinolfi, 1978). People in relationships also protect themselves from beauty by ignoring it. Research shows that when we're thinking about love we automatically ignore attractive members of the opposite sex, probably to protect our feelings about our long-term partner (Maner et al., 2008). Gender and jealousy Most of the research has been done on heterosexuals but it's possible similar biases operate for gay people. For both gay and straight, the extent of the biases probably depends on how attractive you are (or at least how attractive you perceive yourself to be). People who are themselves attractive probably don't feel as defensive around other attractive people, so the biases are likely to be weaker for them. Although we all know about the benefits of being beautiful, it's easy to forget the pitfalls. This psychological research is a reminder that beauty can be threatening. It can threaten our relationships, our work and our image of ourselves. We admire it and defer to it, but sometimes we have to defend ourselves against it. POSTED BY WARREN DAVIES 34 COMMENTS Is beauty just a cultural thing, based on whatever the common consensus is at any particular time? Or is there a ‘true beauty’, that we find in all cultures and times? Actually it’s a little of both. Do you want to know which aspects of ‘beauty’ are arbitrary, and which seem to be biological? Or whether stick thin models are truly beautiful, or just an artificial fad? Then keep reading! A strange event got my mind onto this topic. I was in Primark, a discount clothes storehere in Leeds. An interesting peculiarity about this store is that its layout makes it impossible to get to the men’s section without walking through the women’s underwear section. Having no other option, I made my way through this mysterious section of the store. As I slowly walked towards my destination, I saw someone from the corner of my eye who caught my attention, and my head instinctively moved to her. And there she was, in all her glory. An industry-standard ‘female’ mannequin. I’d just walked through a women’s underwear section, which, being a busy Saturday afternoon, was filled not only with lots of women’s underwear, but also lots of women, and a mannequin is what catches my eye. Maybe that’s an interesting peculiarity about me? No… don’t open that door… Sexy? Why did the mannequin catch my eye? The mannequin’s job is display the clothes in the best possible light. It’s a hard job to get into – the hours are long and employers will only hire you if you’re the epitome of attractiveness; because the same item of clothing worn by two people will generally look better on the more attractive one. ‘Male’ mannequins don’t have sunken chests and pot bellies, do they? The idea is to make you think you’ll look like that, if you’d only purchase the item of clothing. Fair enough. But, why do they look like they do? Why am I supposed to find this particular shape and size woman attractive? I looked into it, but stuck to female beauty, because (a) it’s a more interesting topic (don’t ask how long I spent “researching” pictures), and (b) it has more relevance to issues like body image concerns, the effect of the media, and so on. Eye of the Beholder We can start to answer this question by looking at what different cultures and times have held to be beautiful. If there is wide variety, we can say beauty is mostly cultural. If there’s wide agreement, we can say it’s biological. The classic comment I got while chatting to people about this, is that although “thin is in” right now, in the past, fat was desirable. Not ‘curvy’, but actually overweight. I wondered if this was actually true. Here are a couple of adverts. The left one’s from 1885, the right one from roughly 100 years later: Things have changed since 1885! Though to be fair I did pick both of these specifically to illustrate my point, so they don’t really prove anything. To find more evidence I searched the web, looking at how different cultures across time had depicted women in their art. I don’t have time or space to give a full rundown, but here’s some stuff I found out: Women through time The oldest known representation is the Venus of Hohle Fels. It’s around 35,000 years old, and is most clearly an overweight woman. Of course there’s the work of Flemish artist Paul Peter Rubens in the early 1600s, who influenced the ‘Rubanesque’ movement. Rubens displayed women as pale and plump; this was considered attractive. For example, have a look at his painting, Venus at a Mirror. This is the same Goddess of love and beauty who was depicted more slimly in other times. Slim women got their fair share of attention too. The Egyptians consistently portrayed a more slender ideal in their art, similar to the current trends. See the painting here, from the Tomb of Nakht, around 15th c BCE. Also, based on the paintings I found, the Chinese also preferred the slim look. Weight wasn’t the only factor. For example in Elizabethan England (1558-1603), beauty was pale skin and a plucked forehead! Yes, the hair was plucked to make the forehead appear larger. Not sure where that one came from, but pale skin was a sign of wealth, partly because the ingredients of the cosmetic of choice to achieve this look were rather expensive, and also health because if your face was clear and pale you probably didn’t have small pox. I didn’t do an extensive study of all cultures prefer, but it’s pretty clear that there’s been a lot of variation over time. So far, beauty does look like it’s in the eye of the beholder. Metal necks, ceramic mouths and silicone breasts Even within the cultures of the world today, there exists massive variation in what is considered beautiful. It’s amazing how creative we are with this; all manner of adornment, tattooing and manipulation of body parts are linked to beauty. Again, not a comprehensive study but just a few points: In many parts of Africa, obesity is desirable – it is associated with abundance and fertility. In some areas, girls go to “fattening farms” – much the same in principle to health farms and gyms – a cultural institution aimed at increasing the appearance and charm of its clientele by placing them more in line with the current consensus. This preference was also found in a study in 2008; in the US, men preferred a body shape thinner than the average, while men in Ghana preferred a body shape that was heavier than the average. (1) Again though, we find that there’s more to beauty than body weight. The Padaung women of Southeast Asia like to place metal rings around their necks. They start this practice from a young age, and over time, the rings lengthen the appearance of the neck, increasing their desirability. This has lead to an imaginative nickname: “Giraffe Women”. In some African tribes, large ceramic and wooden plates are held in the mouth to stretch out the lips. Bigger lips = more desirable. Eventually, the lips have stretched so much that the whole plate can be pushed into the mouth with ease! Perhaps strangest of all is the modern West. Many women undergo surgery to alter the size of their breasts, waists and lips. Other surgical procedures are also common, usually based around increasing the appearance of youth. Imagine if Western culture had evolved to desire mouth-plates instead of silicone breasts. Imagine women on the cover of Vogue holding ceramic plates in their mouths, or Pamela Anderson running down a sandy Californian beach, mouth-plate bouncing up and down as she goes. It sounds ridiculous, but is it any more ridiculous than putting lumps of silicone in your breasts? Or spend all your time and money to afford the liposuction cost of thousands of dollars? All over the world, people go to incredible lengths to match up to the standards of beauty their culture endorses. At first glance these standards do not appear to be consistent. When a culture changes, its standards of beauty often change with it. So to a certain extent, beauty is ‘democratic’, decided by whatever the people happen to prefer. But there’s more to this story than differences. For example, even though “thin is in” at the moment, it’s not true that every thin woman is considered beautiful, is it? You couldn’t replace a Playboy centrefold with a random girl of equal weight. So there must be something else going on, other than cultural influences. Perhaps the answer to what this is lies in what the different cultures agree on. We’re not so different after all Evolutionary psychologist Devendra Singh discovered that all around the world, men have a preference for women with a low waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) – A waist that is relatively thin and hips that are relatively broad. This is regardless of the actual weight of the woman. The magic ratio is 0.7; here’s an example you might recognise: (2) Marilyn Monroe – 0.7 waist-to-hip ratio If you zoom in so that the hips measure 20mm, you’ll find the waist measures 14mm – a perfect 0.7 WHR. This ratio is consistent in beauty icons across time and culture. Audrey Hepburn had it, the average Playboy centrefold is 0.68: even the Venus de Milo has a WHR close to 0.7. And a relatively thin waist has been seen as attractive through time – a study of English and Chinese literature consistently found references to thin waists in descriptions of women considered beautiful at that time. (3) So what’s the attraction to this particular shape? It’s because a favourable WHR suggests that a woman is young, healthy, and fertile. It’s a signal of genetic fitness and a good choice for a mate. Women whose fertility has been impaired tend to have higher WHRs, and unhealthy, starving women cannot maintain large buttocks and breasts – they need to use this fat as fuel. Not surprisingly then, the magic 0.7 ratio is a preference shared in almost all cultures studied. WHR provides very important information to a species whose main drives are to survive and reproduce. Although there is some controversy over just how universal the 0.7 WHR preference is, there is reason to believe that even if fads and fashions change, this preference would remain – to so some extent.(4) Face the Facts One thing we haven’t looked at yet is facial beauty. This is typically studied by showing photographs of faces (or actual people sometimes) and asking participants to rate their attractiveness on a scale. In a massive meta-analysis of over 900 studies of this kind, psychologists discovered a huge agreement both cross-ethnically and cross-culturally on which faces were attractive. This analysis strongly disagrees with the idea that “beauty is in the eye of the beholder”, and suggests there’s something universal and genetic about facial attractiveness – something we all recognise. Three important aspects seem to be symmetry, clear skin, and averageness. The more symmetrical a face is, the more attractive it seems to us, and when a group of faces are morphed into one by taking the average of all their proportions, that artificial face is usually seen as more attractive than any of the individual ones. Researchers did exactly that with photos of entrants to the Miss Germany contest. The average face was rated more attractive even than the eventual winner. Here ‘she’ is on the left. But, it’s not purely averageness that is attractive, because several unattractive faces morphed into one is not seen as more beautiful than a prototypical attractive face. (By the way, check out Beauty Check, where this photo came from – it’s an excellent site and their study is great fun too). Don’t forget to indicate! Looking at the evidence, a certain portion of the beauty pie is taken up by biological preferences inherent in most, if not all, humans – the indicators of health, fertility, and good genes. The rest is taken up by cultural preferences. Why do societies differ in these ways? Are they just arbitrary? Way back in time, did a group of high-status people in a tribe decide that long necks were sexy, and dictate that preference to their subordinates, eventually spreading the idea through the whole tribe? Partly, but even cultural preferences are indicators in their own right. They might signal things like health or whether a person has reached breeding age, but the thing about health is that it looks pretty much looks the same wherever you live. Other things might look differently in different areas – for example, wealth. There seems to be a pattern between body weight preference and wealth – although the specific weight that is used as this marker seems to differ across cultures. Researchers Sobal and Stunkard did a large review of studies that looked into both body weight and socioeconomic status. They found that in rich countries, the correlation is negative – the richer you are, the thinner you tend to be – and in poor or undeveloped countries the correlation is positive – rich people tend to be overweight. (5) The reasons for this are unclear, but it’s thought to go something like this: in a poor society you need to be wealthy to become fat, and if you’re a hungry person in a poor society, wealth is very attractive. So overweight people suddenly become appealing. Also, more weight is seen to relate to maturity, and it’s useful to have mature people around in hard times. However, in a society that’s generally rich, these preferences aren’t activated, which allows thinner body ideals to evolve more often in these places. Another interesting study found that men going in to a canteen reported that they preferred heavier women than men going out of the canteen. Hungry men prefer heavier women. So if you hate the thin ideal and want a way to get rid of it, now you know how – starve all the men in the society! (please don’t, though). (6) What is beauty? Combining these findings, we come to a basic formula: Adherence to social consensus + Genetic Fitness = Physical beauty Social consensus will be things like the current body size preferences, fashion/adornment preferences, and so on. Genetic Fitness is WHR, facial symmetry, and things like that. So take a genetically fit (‘biologically attractive’) woman, and throw her in any space and time. Provided she can match up to the status quo of that time, she’ll always be a catch. And even if she didn’t match up, she’d probably be seen as attractive to some extent. Likewise, a woman who isn’t as genetically attractive can ‘trade up’ by adhering to the social consensus. In other words, take Jessica Alba, and fatten her up, or use brass rings to make her neck seem longer, or pluck her hair line back and make her skin pale – and she’d still be considered beautiful in Ghana, Northern Thailand, or Elizabethan England, respectively. Do all three, of course, and she’d be an absolute smash in a goth club. I’m being superficial I’m being superficial on purpose here, because I just wanted to look into beauty. There’s more to attractiveness than physical beauty of course – personality, how you carry yourself, confidence, and all kinds of other things – although I know it doesn’t seem that way, because our culture is very superficial. The only thing is, I don’t know how much of the attractiveness pie is taken up by physical beauty, and how much is taken up by these other things. Maybe that’s a topic for another day. Is it right or wrong for a society to be as focused on physical beauty as we are? I don’t know, but it’s clear that we’re not alone on this – through time and space, people have altered their bodies to look more attractive. All manner of cosmetics, paintings, decorations, piercing, exercise regimes, scarification and accessories have been used. But all of these practices are essentially arbitrary, and relevant to a specific culture at a specific place and time. They establish connections with the norms of that time, or to a particular group within a society. But it’s useful to understand that apart from the biological markers of health and fertility, there’s no definition of beauty that isn’t considered ugly in another place or time.