03-PolicyNoteonShelterandRecoveryV2

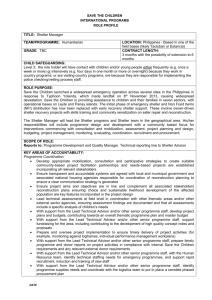

advertisement

Policy Note on Recovery, Reconstruction and Shelter, for Shelter Actors – DRAFT This Policy Note is part of the group of tools produced by the Global Shelter Cluster Working Group on Shelter and Recovery, to support best practice in Shelter, Recovery and Reconstruction after disaster. This policy note builds upon other documents produced for the Working Group on Shelter and Recovery, notably the ‘Definitions of Shelter, Recovery and Reconstruction’ document, as well as building upon the work done in recent reports and guidance documents by other practitioners. This policy note is divided into five sections: Introduction and Summary of Needs for a Policy Document Policy Principles for Best Practice in Shelter, Recovery and Reconstruction Stakeholders and Coordination for Recovery and Reconstruction in Shelter Programming Initial-Stage Activities and Approaches for Supporting and Facilitating Recovery and Reconstruction Efforts References and Resources Section 1. Introduction and Summary of Needs for a Policy Document The Global Shelter Cluster Shelter and Recovery Working Group has recognised the ‘need to better understand reconstruction processes, stakeholders and technical issues in the early stages of a response to allow for comprehensive and relevant strategy development, planning and implementation of sheltering options,’ in order to ‘address the key challenges of interconnectedness through different phases of the disaster management cycle.’1 Experience in recent disaster responses has highlighted the gaps in strategy and policy guidance needed to ensure that limited resources are used to the best effect, to kick-start recovery from the earliest possible moment during Shelter programming. Furthermore, there is the need to ensure that there is a continuum of support throughout the entire process from emergency to recovery, and not just during the first weeks or months, when an emergency has a higher media profile. This continuum of support may need to continue over the lifetimes of different Clusters or other coordination forums, and to have clear strategic connections with national-government development policies, once there are no further humanitarian needs. There is a continued need firstly to advocate and mainstream recovery approaches in the Cluster members' programming and ensure that programmes have a longer view and “Rough Inputs for the Shelter and Recovery Working Group Objectives”, Global Shelter Cluster internal document, 2013. 1 impact, by linking their emergency efforts to more sustainable development goals. The second objective of a Shelter and Recovery policy, is to make sure that when emergency efforts are being scaled down, there are still the offices and people in place to ensure that the data (often of large volume), information, initiatives, programming, funding, and groupings of actors, have a continuation of support until the affected population (and a re-capacitated government) recover their capacity to stand by themselves. The lynchpin of this Shelter and Recovery policy is that it should work in both ways, influencing organisations in looking at the longer term, as well as anchoring these initiatives into more permanent or established structures. Section 2. Policy Principles for Best Practice in Shelter, Recovery and Reconstruction This list of key policy principles to be applied by the Shelter Cluster and its partners, for supporting Recovery and Reconstruction, is taken from lists provided through other guidance documents, and ongoing work and discussions with practitioners. The list is focused in two ways: Firstly, the principles contained in the list are specific to policy concerns for Shelter, Recovery and Reconstruction, and as such do not include key principles for all humanitarian programming (e.g. “Do No Harm”) which may be found widely in numerous other guidance tools. Secondly, whilst the list does refer to technicaldesign or engineering issues from a policy perspective, it does not offer detailed technical guidance. Those seeking such guidance should consult the relevant technical resources provided on-line by the Shelter Cluster, and by many individual Shelter Cluster partners. This list draws heavily upon (and in some cases quotes or abbreviates) recent work by Ian Davis, Shelter Center, UN-Habitat, Habitat for Humanity, and the Cluster Working Group on Early Recovery (see the list of resources in the last section of this document). 1. Reconstruction begins on Day 1, the day of the disaster, started by the first responders, the affected communities themselves. The actions towards Recovery and Reconstruction undertaken by those communities are a process, and often incremental in nature. Any support given to those communities by humanitarian shelter actors, should then be on the same basis. 2. Ground early recovery interventions on a thorough understanding of the context and build on and/or reorient ongoing development initiatives to ensure they contribute to building resilience and capacity in affected communities. 3. A recovery strategy strengthens the livelihoods of survivors and builds the community’s economic base. A good reconstruction policy helps reactivate communities and empowers people to rebuild their housing, their lives, and their livelihoods. Community members should be partners in policy-making and the leaders of local implementation, so use and promote participatory practices, and support the affected population in making informed choices. 4. Humanitarian organisations should ensure national ownership of the early recovery process through the fullest possible engagement of national and local authorities in the planning, execution, and monitoring of recovery actions. By doing so, they may build capacity, and also strengthen accountability systems so that the population can hold governments, local authorities, and their international donors to account in the implementation. Government offices should adapt to create a structure which is organizationally effective, can make full capacity of the resources available for Recovery and Reconstruction, and which can provide strategic direction for those activities. 5. Reconstruction policies and plans should be financially realistic but ambitious with respect to disaster risk reduction, and the multiplier-effects possible in an effective programme for ‘build back safer’. Clusters and humanitarian organisations should advocate for funding to cover all phases of Recovery, and to bridge any gaps between emergency response and permanent reconstruction. At the same time, implementation approaches which support the greatest number of the population in a cost-effective manner should be prioritised. 6. Civil society and the private sector are important parts of the solution, and should be included strategically in humanitarian support, and in the coordination of that support. In some cases, humanitarian organisations may need to take an active role in developing constructive and inclusive working relationships between civil society organisations and government institutions. 7. Reconstruction must be sustainable, and this means ensuring that vulnerability to disasters is not rebuilt. Designs and location-siting must include risk reduction and/or conflict prevention measures. These measures must be undertaken not only for individual dwellings, but for settlements, neighbourhoods and cities. This need is high in urban or peri-urban areas where the scale of the disaster is often caused by informal settlements in hazard-prone locations. Ensure that technical assistance complements rather than replaces existing capacities, and is seen by national actors as supportive rather than directive in the construction of adaptable, climatically and culturally appropriate shelter, settlements, housing and neighbourhoods. 8. Promote equality and support settlement and reconstruction for all those affected. Ensure that any Shelter or Reconstruction programming is not biased towards only those who already have some degree of security of tenure, but takes into full consideration those whose vulnerability includes lack of access to land. Aim to ensure that land and property tenure issues are resolved with all stakeholders. 9. Assessment and monitoring can improve reconstruction outcomes. Maintain a continuous assessment of risk, damage, needs and resources, built into seasonal cycles, and any seasonal variations in construction capacity or other variations in available resources. 10. Reconstruction strategies should be integrated into regional and urban masterplanning, with Shelter and reconstruction efforts guided the same. Relocation disrupts lives and should be minimised – avoid relocation or resettlement, unless it is essential for reasons of safety, and minimise duration and distance, when displacement is essential 11. Undertake contingency planning, and recognise that in countries with short cycles of natural disasters, contingency-planning and disaster-risk-management should be centrally integrated into the Recovery process. 12. Ensure integration of other cross-cutting issues such as gender, environment, security, human rights, and HIV/AIDS in assessment, planning, and implementation. Section 3. Coordination for Recovery and Reconstruction in Shelter Programming Ensuring that local stakeholders are the focus and the drivers of Recovery must be based on the following key principles. Some of these principles are universal principles for a successful policy of coordination, but all are essential for support to a successful Recovery: Decentralise – to the degree appropriate, ensure that coordination, decisionmaking and information sharing is conducted at the local level. Take the discussion to the actors – don’t expect that all stakeholders can or will come to a discussion: in many cases, discussions can be more effectively brought to local stakeholders’ own forums, whether they be for local communities, local NGOs or local municipalities. Ensure space for all voices to be heard – work in awareness of local culture, to ensure that the voices of those who may be marginalised, because of their gender, ethnic grouping, or because they are landless, are still included in informationsharing and decision-making. Make the language a means of communication, not a barrier – take the responsibility of facilitating translation or local-language discussions, and work with local actors to use graphics or other forms of media for key messages. No sectoral silos – Recovery in communities does not split into sectors, and particularly at the neighbourhood level, partnering for a more holistic approach will better reflect the full range of priorities amongst disaster-affected households. No out-of-bounds topics – ‘Shelter’ discussions should never dismiss participants’ wishes to also discuss reconstruction, urban planning, water supply, or any other relevant topic, just because those topics fall outside of the mandate of the humanitarian organisations present. Act as the vertical messenger and the vertical introducer – Humanitarian organisations have the unique position in disaster responses, of being able to make the links between different groups, including from the national (or international) to the local. Section 4. Initial-Stage Activities and Approaches for Supporting and Facilitating Recovery and Reconstruction Efforts In all post-disaster settings, it is the disaster-affected population themselves who are the first responders, and the first to engage in reconstruction efforts, and in the majority of the cases the only ones to engage directly in the reconstruction of their own homes. In order to support this process, a number of approaches can be undertaken by other actors. Often, it is the ability to consider the bigger picture, and approach Recovery at a settlements- or city-wide level, and the ability to marshal external resources, which becomes the added value to individual-household efforts, brought by the humanitarian sector. Needless to say, not all approaches may be appropriate for all post-disaster situations, and practitioners will have to judge which ones may have the most positive effects in any specific response: in most cases a strategic combination of a selection of the activities listed below would offer the best approach. In all cases though, the activities and approaches listed below must be guided by the overarching principles of being community-driven and community-focussed. In the Shelter-sector guidance document Urban Shelter Guidelines (2010), there are listed 18 possible types of responses, all of which may play some role in the Recovery process, if done correctly, and if combined strategically with other activities. The following activities and approaches are those that are not mainly concerned with the distribution of relief items, and they make clear demonstration of the variety of ways in which initial activities and approaches can have a positive affect upon the Recovery process: 1. Infrastructure and settlement planning support – In the first phases of response, infrastructure and settlement planning support can take a variety of forms, all of which have shown to be key to Recovery, from rubble-removal to repair and installation of water supply to facilitate a return to original neighbourhoods, to the planning of transitional or permanent new settlements. 2. Environmental and resource management – A Recovery cannot be successful, if the process has resulted in the destruction of environmental or other resources, or the construction of settlements in environmentally hazardous areas. 3. Supervision and technical expertise – The provision of technical expertise or knowledge-transfer during the construction of shelters or housing is a key area with multiplier-effects, providing skills which may be used later in further construction, or upgrading of housing. 4. Legal and administrative expertise – In a number of recent high-profile emergencies, the key barriers to Recovery have included the lack of civil documentation, or the lack of access to land or security of tenure. The early establishment of activities to support disaster-affected communities with legal counseling or assistance can provide some remedy to this. 5. Information centres and teams – A highly effective way of reaching not just those who have lost housing in a disaster, but all those in the community with needs for information or training on hazard-resistant construction, the construction of community infrastructure, or legal and administrative processes, is through the use of information centers and / or information teams. 6. Capacity-building and training – There is a wide range of ways in which capacity-building and training can be undertaken, starting with the staff and partners of the humanitarian organisations. But the most enduring of approaches are those which engage in capacity-building and training for national and local government and civil society, who will have the long-term responsibility for development goals and strategies once the humanitarian response is complete. 7. Labour – Whether the labour is provided through community mobilisation, or through contracting, the added stimuli to the local economy, the psychological benefits from being involved in the reconstruction work, and the actual deployment of manpower in critical activities (such as rubble-removal) mean that this sort of activity can have a number of positive benefits for Recovery. Particularly in an urban setting though, care needs to be taken to ensure that people are not being taken away from their longer-term livelihoods, by short-term humanitarian projects. 8. Cash or Vouchers – The flexibility of use of cash or vouchers not only allows each household to prioritise their own Shelter and Recovery needs, but also ensures a maximum possible stimulation of the local economy. The use of this approach also ensures that for those with the resources to start permanent reconstruction early, support is immediately available. 9. Loans and credit – Whilst household loans programmes tend to be undertaken more in the long-term development context, recent examples of credit given to families in post-disaster situations include rental and housing support, thus ensuring that the families have adequate shelter without incurring whilst being able to manage their debt in a sustainable manner, so that personal resources can be used to the greatest extent possible upon reconstruction and livelihood reconstitution. 10. Insurance and guarantees – Although this approach is not typically taken by NGOs with a non-permanent presence in the country, there is more and more awareness in middle-income countries with high risks of natural disasters, that the sustainable way for a country to manage its exposure to natural disaster through creating wider accessibility to insurance for housing. Whilst NGOs may not be the channel for such activities, they can advocate for such programmes to be done in a responsible manner, and can offer counseling on how to access such opportunities. 11. Market interventions – Starting with the creation of post-disaster market-analysis tools, there has been an increasing awareness of the effects which Shelter programming can have on local markets. Opportunities to make positive market interventions in the first phases of Shelter programming may include small loans for workshop equipment, voucher schemes which funnel funds through certain targeted segments of a market, repair of market places, or low-cost sale of materials to local retailers. Section 5. References and Resources This Policy Note builds on the work done by a number of organisations and authors, and a more complete list of useful strategy- and policy-level resources is given in the separate document created by the Working “Group, Shelter Recovery and Reconstruction Key Resource List”. There are a small number of resources which were particularly helpful for the drafting of this document though, and whose ideas were central to those contained here above: Corsellis, Tom, and Vitale, Antonella. Transitional Settlements and Reconstruction After Natural Disasters. UNOCHA, 2008. Davis, Ian. “What Is The Vision For Sheltering And Housing In Haiti? Summary Observations of Reconstruction Progress following the Haiti Earthquake of January 12th 2010”. UN-Habitat, 2012. “Guidance Note on Early Recovery”. Cluster Working Group on Early Recovery, 2008. “Pathways to Permanence”. Habitat for Humanity, 2012. Suvatne, Martin, and Crawford, Kate. Urban Shelter Guidelines. NRC/Shelter Centre, 2010.